In this essay, art historian Anna Pravdová delves deep into the MoMA Archives to highlight the Museum’s first exhibition of Czech art. Opened in May 1943, at the height of World War II, the exhibition War Caricatures by Hoffmeister and Peel featured works on paper by Adolf Hoffmeister and Antonín Pelc, recent immigrants and passionate anti-Fascists. It was successful due to its strong sarcastic humor, which Americans embraced in a time of crisis. This first part of the essay looks at the steps that led up to the exhibition, namely Hoffmeister’s and Pelc’s journeys to the United States.

In addition to Pravdová’s commentary, you can access the exhibition’s checklist and press release in MoMA’s comprehensive online exhibition history archive here.

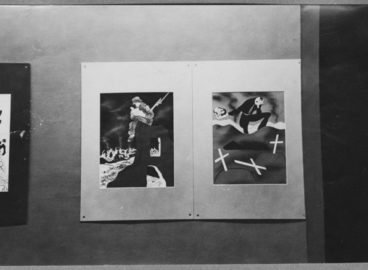

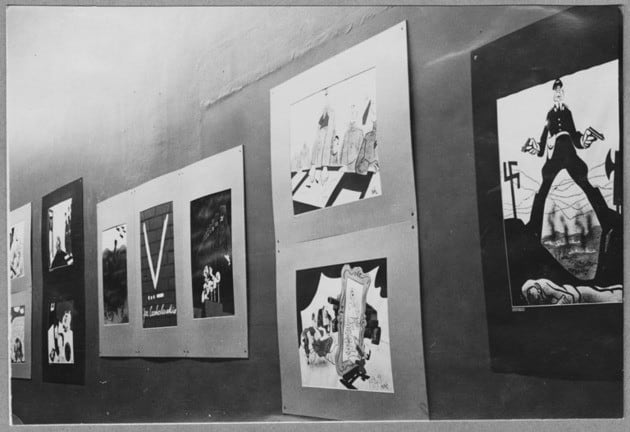

On May 12, 1943, The Museum of Modern Art opened the exhibition War Caricatures by Hoffmeister and Peel in its ground-floor gallery.1“Peel” was the pseudonym of Antonín Pelc and the name with which he signed the caricatures he drew in the United States. Comprised of thirty-four works by Adolf Hoffmeister and Antonín Pelc, it was the Museum’s first exhibition of Czech art.2At least according to New-Yorské listy. See “Výstava čs. karikaturistů Hoffmeistera a Pelce v Museum of Modern Art,” New-Yorské listy 69, no. 112 (May 11, 1943): 5. While it did not have a catalogue, evidence of the exhibition, in the form of photographs and checklists, remains in the MoMA Archives. This exhibition is significant because of its timing—it took place during the German occupation of Czechoslovakia, when many intellectuals, including Hoffmeister and Pelc, had fled or were fleeing the country to save their lives.

Coming to America: Unwilling Tourists across Three Continents

Well-known anti-Fascist artists, Hoffmeister and Pelc spent most of World War II in the United States, their paths to this country were complicated ones. The German army occupied Czechoslovakia on March 15, 1939, giving rise to the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Under new rule, many artists and other intellectuals were forced to flee as they had made no effort in the preceding years to hide their anti-Fascist stance, openly and categorically condemning the rise of Fascism and the Nazi regime. Such was the case of caricaturist and writer Adolf Hoffmeister (1902–1973) and caricaturist and painter Antonín Pelc (1895–1967), both of whom attracted the attention of the German authorities not only through their work but also through their friendships with German anti-Fascist artists (who had escaped Nazism by fleeing to Prague) and their participation in the 1934 International Exhibition of Caricature and Humour, held at the seat of the Mánes Association of Fine Artists in Prague and a significant manifestation of an anti-Fascist stance on the part of the artists represented. In the name of Third Reich authorities, the German ambassador protested against this exhibition and asked that some of the most violent anti-Nazi works be removed, mainly those by John Heartfield and Antonín Pelc.

In April 1939, shortly after the German occupation, Hoffmeister and Pelc left for Paris. Like many Czech Francophiles, they believed that France would serve as a center for the fight for Czechoslovak independence, as it had during World War I. Upon Hoffmeister’s arrival, the Committee of the International Association of Writers for the Defence of Culture gave him the task of organizing the House of Czechoslovak Culture into a cultural center and refuge for Czechoslovak writers in exile. Eventually, in August 1939, it became a residence for representatives of Czechoslovak culture in France: painters, musicians, professors and journalists.3Namely painters Adolf Hoffmeister, Antonín Pelc, Alén Diviš, and Maxim Kopf; Slavicist Klement Šimončič; journalists Rudolf Šturm and Lenka Reinerová; and violinist Jan Šedivka. For more details, see Anna Pravdová, Zastihla je noc, Čeští výtvarní umělci ve Francii 1938–1945 Caught by the Night. Czech Artists in France 1938–1945; and Tomáš Pospiszyl and Vanda Skálová, Alén Diviš 1900–1956 (Prague: Nadace Karla Svolinského a Vlasty Kubátové, 2005). Under the mistaken impression that the House was actually the headquarters of the Central Committee of the Czech Communist Party in exile (which was banned in France as were other Communist organizations after the German-Soviet Pact), the police raided it on September 18, 1939, taking all its residents into custody. They were subsequently charged with espionage, sentenced to serve six months in La Santé prison in Paris, and then interned in various detention camps on French territory.4Adolf Hoffmeister described these adventure in his book published in 1941 in the United States under the title The Animals Are in Cages and in 1942 in the United Kingdom under the title The Unwilling Tourist.

After their release, a group of four artists, Hoffmeister, Pelc, Alén Diviš, and Maxim Kopf, boarded a ship, in the South of France, bound for Casablanca, Morocco, where they were detained as unwanted aliens. Once released, each went his own way: Hoffmeister secured a visa and a place onboard a ship to Lisbon, and from there he reached the United States. Pelc and the painters Diviš and Kopf spent several more months in a detention camp before securing passage to Martinique on the same ship as André Breton, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Anna Seghers, Wifredo Lam, and other outstanding personalities fleeing occupied France. Upon arriving in Martinique, all the passengers were, once again, interned. After two weeks, Pelc, Kopf, and Diviš managed to embark for the United States, aboard a ship on which André Masson and his wife and two sons were also passengers. They finally arrived in New York City on May 29, 1941.5See New York, Passenger Lists, 1820–1957, National Archives in Washington, DC.

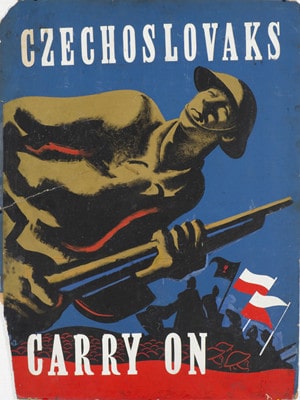

“When we reached the United States, we saw America as a paradise after all that running from jail to jail and camp to camp. I was so happy finally to be left alone that I started to paint and draw immediately,”6Vladimír V. Bernášek, “Nabroušenou tužkou proti fašismu. Rozmluva s A. Pelcem,” My 46, no. 17 (April 27, 1946): 3. recalled Pelc in 1946.7When he was back in Czechoslovakia. After 1948 he became one of the the official artists of the Communist regime. After a year’s break, he once again took up political caricature and propaganda, drawing in the United States on behalf of occupied Czechoslovakia. According to the testimony of Stanislav Budín, editor in chief of New-Yorské listy, the Czechoslovak newspaper published in New York,8Stanislav Budín, Jak to vlastně bylo (Prague: Torst, 2007), 267. the Czechoslovak Press Agency supplied the matrices of Pelc’s caricatures to the Czechoslovak refugee press once a week. Pelc also drew posters promoting the Czechoslovak Relief Committee, such as Help Czechoslovakia, which was published in 1943 to benefit the United Czechoslovak Relief9This Chicago-based organization was founded in April 1943 by merging the Czechoslovak Relief Committee and the Association of the American Friends of Czechoslovakia. in its effort to support one of many collections arranged for Czechoslovak refugees and soldiers. Pelc’s poster Czechoslovaks Carry On, from 1942, depicting a soldier with a gun, and silhouettes of Hussite warriors with Hussite and Czechoslovak flags in the background, won an award in the Artists for Victory contest sponsored by The Museum of Modern Art.10For more about Pelc’s activities in America, see Anna Pravdová and Tomáš Winter, eds., Seňorita Franco a Krvavý pes: malíř, karikaturista a ilustrátor Antonín Pelc (1895–1967) Seňorita Franco and the Bloody Hound: The Painter, Cartoonist and Illustrator Antonín Pelc (1895–1967).

Hoffmeister, who had reached the United States four months before Pelc, spent his first six months in Cleveland, Ohio, and Hollywood, California, with his friends, actors Jiří (later, George) Voskovec and Jan Werich. After arriving in New York City, he became a lecturer. In December 1941, he delivered a lecture entitled “Caricature as a Weapon” at the Workers’ House in New York, and several months later, he launched a “No One Will Win the War for Us” lecture tour across the United States.11For more about this tour and Hoffmeister’s activities in America, see Karel Srp, ed., Adolf Hoffmeister (1902–1973) (Prague: Národní galerie v Praze, 2004).

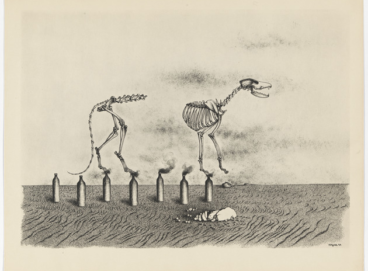

During this time, Hoffmeister and Pelc participated in several joint exhibitions and created drawings for magazines. Pelc was especially successful in this respect, publishing caricatures under the pseudonym Peel. But he had to adapt his drawings, as the Americans public reportedly did not understand his abbreviated, line-drawn caricatures, and thus he began to produce more descriptive and realistic drawings and gradually also to incorporate more “realistic” collage elements, just as he had done in the second half of the 1920s and early 1930s. His drawings slowly lost their typical poster-like, two-dimensional character, as he resumed incorporating spatial depth. This is best seen in the caricatures he chose to display in the spring 1943 MoMA exhibition War Caricatures by Hoffmeister and Peel.

This is the first part of a two part essay by Anna Pravdová on the artists Adolf Hoffmeister and Antonín Pelc at MoMA. You can find the second part here.

- 1“Peel” was the pseudonym of Antonín Pelc and the name with which he signed the caricatures he drew in the United States.

- 2At least according to New-Yorské listy. See “Výstava čs. karikaturistů Hoffmeistera a Pelce v Museum of Modern Art,” New-Yorské listy 69, no. 112 (May 11, 1943): 5.

- 3Namely painters Adolf Hoffmeister, Antonín Pelc, Alén Diviš, and Maxim Kopf; Slavicist Klement Šimončič; journalists Rudolf Šturm and Lenka Reinerová; and violinist Jan Šedivka. For more details, see Anna Pravdová, Zastihla je noc, Čeští výtvarní umělci ve Francii 1938–1945 Caught by the Night. Czech Artists in France 1938–1945; and Tomáš Pospiszyl and Vanda Skálová, Alén Diviš 1900–1956 (Prague: Nadace Karla Svolinského a Vlasty Kubátové, 2005).

- 4Adolf Hoffmeister described these adventure in his book published in 1941 in the United States under the title The Animals Are in Cages and in 1942 in the United Kingdom under the title The Unwilling Tourist.

- 5See New York, Passenger Lists, 1820–1957, National Archives in Washington, DC.

- 6Vladimír V. Bernášek, “Nabroušenou tužkou proti fašismu. Rozmluva s A. Pelcem,” My 46, no. 17 (April 27, 1946): 3.

- 7When he was back in Czechoslovakia. After 1948 he became one of the the official artists of the Communist regime.

- 8Stanislav Budín, Jak to vlastně bylo (Prague: Torst, 2007), 267.

- 9This Chicago-based organization was founded in April 1943 by merging the Czechoslovak Relief Committee and the Association of the American Friends of Czechoslovakia.

- 10For more about Pelc’s activities in America, see Anna Pravdová and Tomáš Winter, eds., Seňorita Franco a Krvavý pes: malíř, karikaturista a ilustrátor Antonín Pelc (1895–1967) Seňorita Franco and the Bloody Hound: The Painter, Cartoonist and Illustrator Antonín Pelc (1895–1967).

- 11For more about this tour and Hoffmeister’s activities in America, see Karel Srp, ed., Adolf Hoffmeister (1902–1973) (Prague: Národní galerie v Praze, 2004).