Meghan Forbes examines the ways interwar periodicals blurred the boundaries between art and advertisement, creating international networks of exchange.

The period between the two world wars in Europe marked a moment of intensive artistic and intellectual exchange. One way such exchange was facilitated between the avant-gardes of various countries was in print, some of the better-known examples being L’Esprit nouveau in France, the Bauhaus books in Germany, and the (typically Anglophone) “little magazines” such as Blast and the international project Broom. But the capacity for magazines published in “minor” languages—including Czech, Polish, Serbo-Croatian, and Hungarian—to engage in this exchange and thereby reflect and inform contemporary literary and aesthetic trends beyond their borders, has gone largely unconsidered. The MoMA Library’s current exhibition THE ELECTRO-LIBRARY: European Avant-Garde Magazines from the 1920s helps to correct this oversight, showing how important these magazines are to the history of the interwar avant-garde and to the avant-garde periodical, and gives the visitor some insight into the strategies employed in these magazines, by which their editors engaged in transnational conversations. Through the use of non-textual cues, such as photography and graphic design, as well as the employment of translation and multilingualism, the magazines included in the exhibition, such as Disk and Pásmo (Czech), Zenit (Yugoslav), Ma (Hungarian, based in Vienna), Blok (Polish), and Veshch (Russian, based in Berlin), were able to reach wide audiences at home and abroad, and visually convey their shared affinities.

Karel Teige—artist, theorist, and leader of the Czech avant-garde group Devětsil—described, in his important essay “Images and Fore-images,” the increasing importance of printed matter as artistic production and the ways it had come to permeate the sphere of daily life. He lists these new forms of art as “signs, leaflets, advertisement, illustrated magazines and book covers.”1Karel Teige, “Obrazy a předobrazy” [“Images and Fore-Images”], Musaion 2 (Spring 1921): 55. More so than the book—which is potentially much longer and yet more narrow in focus, takes longer to reach the publication stage, and cannot as easily be dialogic—the magazine was the platform in the interwar period through which the avant-garde could strive to reach a large audience quickly and conversantly.

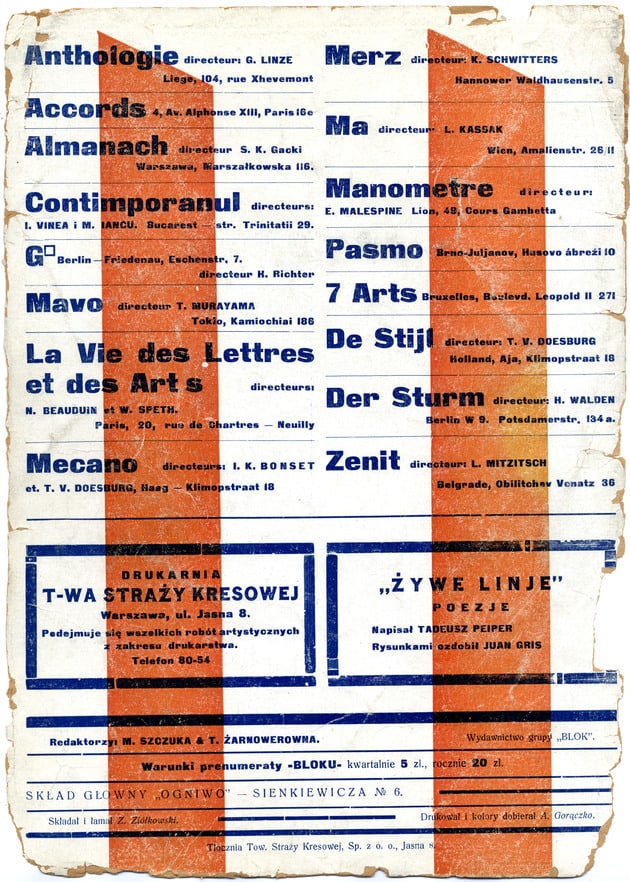

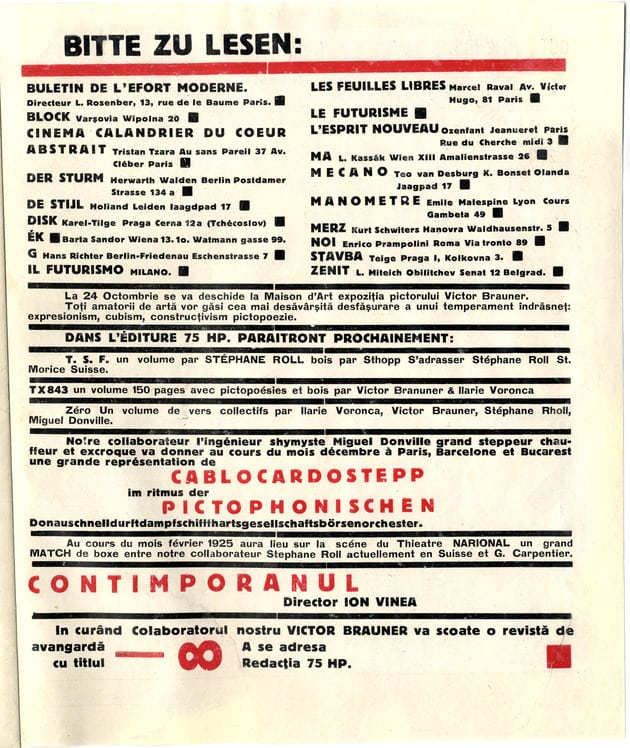

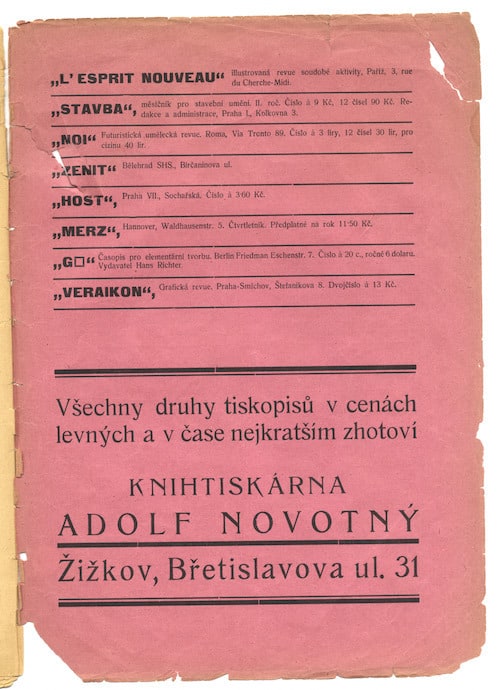

The magazines also kept their readers up-to-date on new publications at home and abroad by typically devoting a significant amount of each issue to the promotion of other magazines and the work of international peers. The editors did not collect advertising revenue for this sort of cross promotion, but rather engaged in it voluntarily to signal an alliance with groups and movements across borders, and most likely with the hope or expectation that the favor would be returned. New Typography—the non-ornamental, Constructivist style that developed in the early 1920s and was almost retrospectively articulated by the German Jan Tschichold in his 1928 book by the same name—was the preferred aesthetic for much for this sort of advertisement, incorporated organically into the content of the magazines. In Tschichold’s manual The New Typography, it is telling that a section dedicated to examples of “Advertisement” is followed by a section on “Periodicals.”

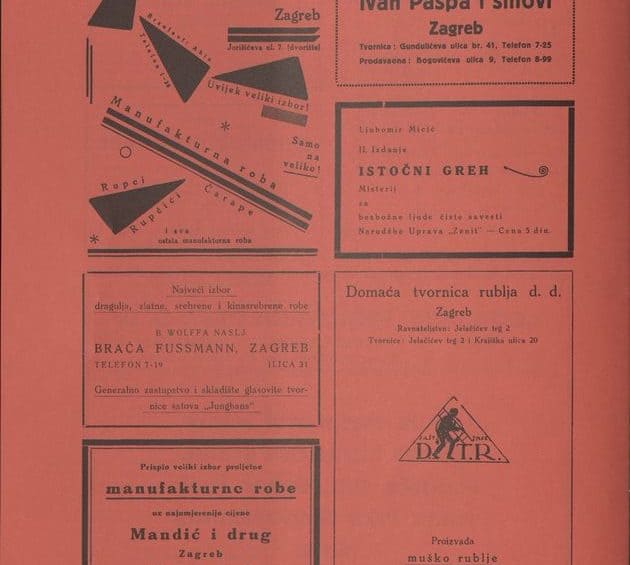

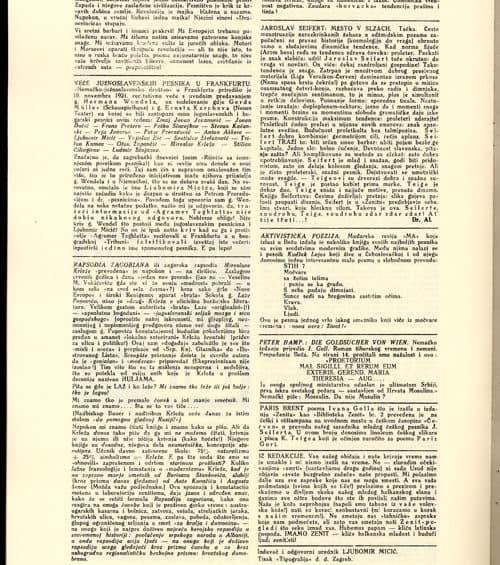

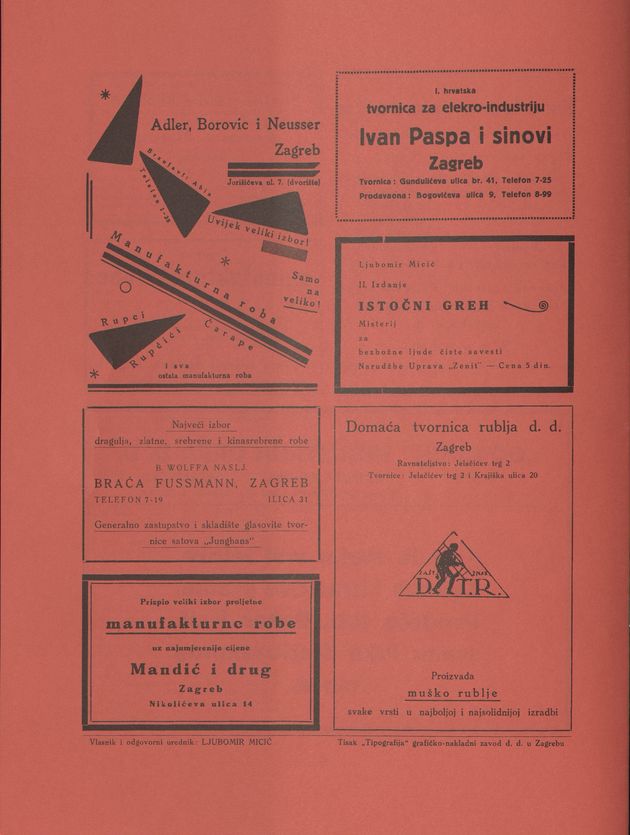

Teige expressed in another, slightly later, essay, “Words, Words, Words,” the ways in which typography could work expediently and democratically across genres—including advertisement—to convey information to the reader: “The eye reads namely what the ear should hear. Modern posters, signs, advertisements and signals grasp the optical meaning of a form, its size, color and layout of typographic material: here the word excels in its optical value.”2Teige, “Slova, slova, slova (Part Three),” Horizont 1, no. 3 (March 1927): 47. Advertising, and advertising theory, were subjects taught at art and design schools such as the Bauhaus, for instance, and the Russian Constructivists employed much the same aesthetic in their advertising work as in their artistic production to promote a socialist agenda.3On this subject, see Christina Kiaer, Imagine No Possessions: The Socialist Objects of Russian Constructivism (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2005). In an example from film, motifs from Walter Ruttmann’s 1921 Lightplay (Lichtspiel) of competing geometric shapes make their way into an Excelsior tire advertisement the following year, in which the figure of a circle morphs into that of a tire, impenetrable to attacking, sharp-edged triangles. Also in 1921, Ruttmann’s triangles were echoed in a (paid) advertisement for a manufacturing firm at the back of the first ten issues of Zenit, in which four bold triangles prod and poke each other, and which the art historian and curator Irina Subotić has compared to Russian Constructivist El Lissitzky’s “typographic solutions.”4Irina Subotić, “Avant-Garde Tendencies in Yugoslavia,” Art Journal 49, no. 1 (Spring 1990): 23. Subotić writes further that is was likely Zenit’s main editor, Ljubomir Micić “who was responsible for the review’s typographical design and advertising.”

Thus, as Michael Cowan has written, there were many notable “synergies between avant-garde aesthetics and advertising,” and it is in light of this fact that the sort of advertisement or promotion under discussion here is in many ways integral to the periodicals’ other content, as opposed to separate from it.5Michael Cowan, “Advertising, Rhythm, and the Filmic Avant-Garde in Weimar: Guido Seeber and Julius Pinschewer’s Kipho Film,” October 131 (Winter 2010): 30. While some of the avant-garde magazines did bring in a bit of revenue from advertising that tended not to read as integrally into the design of a given publication, unpaid advertisement—the kind that served as artistic collaboration—was aesthetically consistent. This form of advertisement typically appeared either as a list—often printed in a bold, sans serif font—publicizing magazines from several different countries, or as an insert wedged somewhere in the body of the magazine, serving as a rally cry to “Read X!” or “Subscribe to Y!” And it would be remiss not to mention here that the editors of these magazines promoted each other as well simply through the publication of content (in the form of poems, articles, reviews, and images) of their peers’ work.

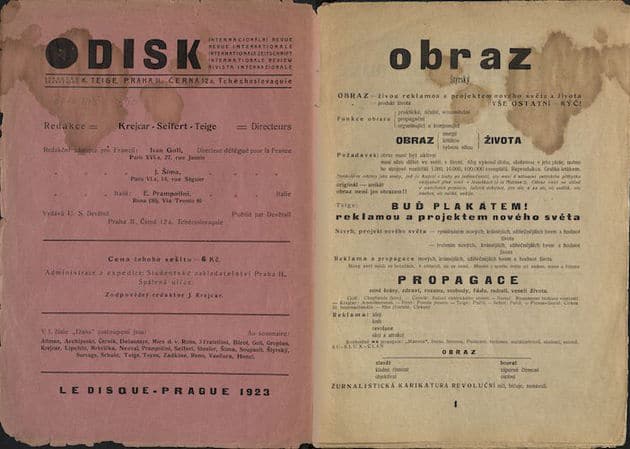

There are copious examples of the ways in which the avant-garde periodicals blur the boundary between art and advertisement in their design and other editorial considerations, and so I will limit my remarks in what follows to a few salient examples from the Devětsil publication Disk, and primarily from the Yugoslav Zenit, which underscore how the mechanics of cross promotion and advertisement worked across the magazines featured in The Electro-Library. The back cover from the first issue of Disk (1923) is representative of the way in which the international avant-garde magazines advertised each other; in this case Czech publications are promoted alongside and indiscriminately from those put out abroad, including L’Esprit nouveau, Noi, Merz, G, and Zenit. Though Disk pushes the limits of what can be described as a periodical—there were only two issues published in total, this first in 1923 and a second in 1925—it is the first major serial publication of Devětsil (which previously had put out two almanacs in 1922, and whose members had collaborated on other publications not explicitly under Devětsil control). It had been a founding goal of Devětsil to have international visibility, and the periodical was central to how the group managed this. The editors of Disk—Teige, the poet Jaroslav Seifert (who would be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for 1984), and the architect Jaromír Krejcar—advertised magazines and published content by non-Czech contributors, and also kept an international editorial staff, which included Yvan Goll in Paris, as the front matter of this first issue shows.

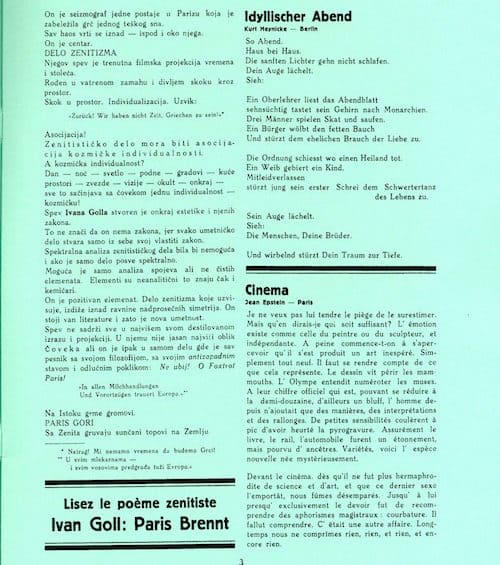

Goll was also an editor for some time at Zenit, his name given equal stature to that of the periodical’s main editor Ljubomir Micić on the covers from issue eight in October 1921 through issue thirteen in April 1922. As the active participation of the bilingual French-German Goll would suggest, the magazine, based first in Zagreb and later in Belgrade, was exceptionally international in scope, publishing content in Serbo-Croatian, German, French, English, Czech, and a few other languages. An exchange between the editors of Zenit and key members of Devětsil had been initiated some years prior to the first issue of Disk, and only a few months after Devětsil was founded in late 1920, and evinces how the avant-gardes advertised each other and forged collaboration not only through unpaid advertisements, but also by publishing content from foreign contributors. Teige wrote to Artuš Černík, another Devětsil member and Brno-based editor, in 1921, reporting that he “spoke with the Prague representative” of Zenit—likely Micić’s brother and collaborator, Branko Micić (who went by Virgil Poljanski in his contributions in Zenit), who lived in Prague for a time—and that there was interest in dedicating a full issue of Zenit to young Czech artists.6Devětsil members came into contact with a group of Yugoslav avant-gardist studying in Prague in the early 1920s. Yugoslav events and activities were even announced in the local papers, such as in the April 12, 1921, edition of the daily Čas (Time), in which a meeting of the “Czechoslovak-Yugoslavia League” at the Old Town town hall is mentioned in a listing of upcoming events. In the years 1920 to 1922, Dragan Aleksić (who also contributed to Zenit from Prague, reporting for instance on Kurt Schwitter’s form of Dada) and Poljanski hosted several Dada evenings in Prague. For more on Yugloslav Dada activities in Prague, see Holger Siegel, In unseren Seelen flattern schwarze Fahnen: Serbische Avantgarde 1918–1939 (Leipzig: Reclam-Verlag, 1992) and, in English, Jindřich Toman, “Now You See It, Now You Don’t: Dada in Czechoslovakia, with Notes on High and Low” in Crisis in the Arts, The History of Dada Vol. 4. The Eastern Dada Orbit: Russia, Georgia, Ukraine, Central Europe and Japan, ed. Stephen Foster (New York: G. K. Hall & Co., 1998): 11–39. Teige is at first reserved in his evaluation of Zenit, describing the group’s aesthetic orientation almost comically as “dadaist futurist-neofuturist” (“dadaistický futurista-novofuturista”) and the magazine as “pretty weak.”7Karel Teige to Artuš Černík, 1921, Památník národního písemnictví (PNP), Artuš Černík Archive (AČ Archive). But, Teige notes, there is the possibility of a small honorarium for Devětsil (always in need of funds), and also that the magazine is “widely distributed,” which would have been welcome advertisement for the young group and its members.8Ibid. Teige reports that Zenit’s circulation amounts to five thousand copies within Yugoslavia, and another two to three thousand across Europe. If this truly was the circulation of Zenit, it would reflect a substantial print run, far greater (by several thousands) then any of the Devětsil periodicals. The unabashedly socialist politics of Zenit would also no doubt have been a strong draw for the left-oriented Devětsil.

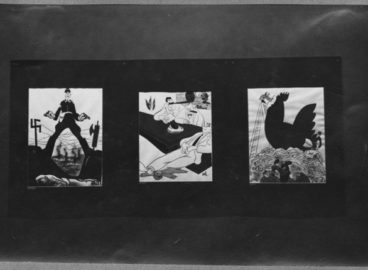

Thus efforts were made to provide Zenit’s editors with materials for the proposed special issue, though the result—issue seven from September 1921—is not entirely dedicated to the young Czechs. All but two of the reproduced images are by Prague artists and early Devětsil members, though the group is represented with Cubo-Expressionist paintings aesthetically quite dissimilar to the slightly later, more Constructivist style of Devětsil by which it is recognized today. And judging from a letter Teige sent to Černík in July of 1921, what comes out in Zenit in September is a significantly stripped-down version of the materials that had initially been sent to the editors, which seem to have also included texts and poems in the Czech original, as well as German translations. In the end, the only text published in this issue to come from Prague is a Dadaist poem, attributed to Poljanski, so in fact not by a Czech but a Yugoslav, and published in Serbo-Croatian.

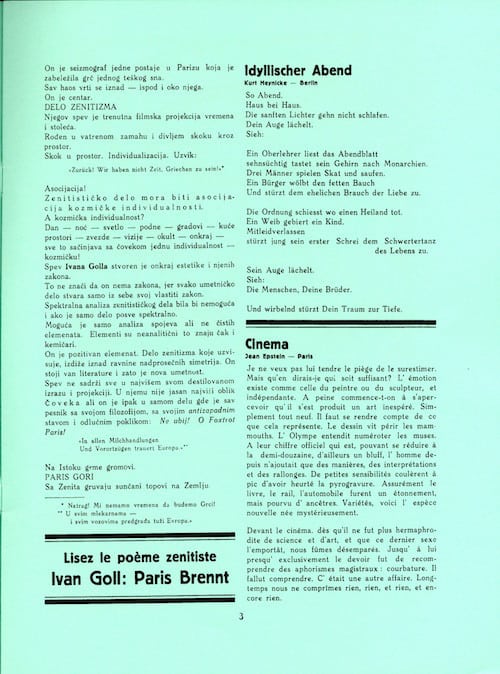

In the November 1921 issue of Zenit (now with Goll as coeditor), a Czech poem does appear—Seifert’s “City in Tears”—though with some spelling errors, including in the title of the poem itself.9Though all Czech verse in Zenit is printed in Czech, in keeping with the magazine’s ardent internationalism, spelling errors such as those in Seifert’s poem suggest that it was for good reason that Teige had written to Černík suggesting that they send work not in Czech, but rather in German or French translation: “Definitely on account of the foreigners we have to send them our German translations and we could also dig up at least some article in French.” [Teige to Černík, 1921, PNP, AČ Archive.] “City in Tears” appears again (now spelled correctly) in issue eleven from February 1922, not in the form of a poem, but rather in a warm review for a book by the same name, in a section toward the back of Zenit on new local and international publications.10As Derek Sayer has written, with City in Tears, published in 1920, “Seifert began his career.” It was dedicated to the Czech communist poet S. K. Neumann and included a preface penned by Teige that was an “uncompromising declaration” of Devětsil’s proletariat leanings. [Derek Sayer, Prague, Capital of the Twentieth Century: A Surrealist History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013): 46.] Its staunchly leftist orientation thus made it a natural choice for a review in Zenit, which had a similar political orientation. Several other Czech books and magazines with which Devětsil was involved are also named on the same page as City in Tears is reviewed, including Host, Proletkult, and Veraikon. In a salient example of how this sort of promotion worked dialogically, below the review of Seifert’s book is an announcement that Goll’s “Paris Is Burning” had appeared in the Czech communist magazine Červen, edited by Stanislav K. Neumann (and which had first been promoted in issue five of Zenit). And indeed, Goll’s poem had appeared (in Czech translation) on the cover of Červen on December 8, 1921.

In this same issue of Zenit, a poem by Černík also appears. And, on the page facing Černík’s poem, an essay by Ilya Ehrenburg is printed (in Serbo-Croatian translation), further highlighting the international, multilingual slant of the magazine, not to mention its Soviet sympathies.11Teige to Černík, July 9, 1921, PNP, AČ Archive. Černík’s poem, “At the House of Moving Pictures,” describes the empathic experience of watching scenes from everyday life, such as lovers embracing, unfold on the screen. Alongside Ehrenburg’s essay is a small reproduction of Vladimir Tatlin’s tower, designed (but never constructed) as a Monument to the Third International, which appears again on a larger scale on the cover of this issue, which names Černík as a contributor to the issue, and also lists Seifert’s book (here, again, spelled incorrectly).

Zenit, lasting not even six years, still had a longer run than any of the major Devětsil publications (which, besides Disk, were the Brno-based Pásmo and Prague-based ReD). Irina Subotić describes how after “periodic prohibition” Zenit “was finally proscribed by the authorities in December 1926” due to its socialist sympathies.12Subotić 21. In the forty-third and final issue of Zenit, a retrospective list of the magazine’s “collaborators” is printed, which shows just how international the publication was. The list includes three Czechs—Seifert, Teige, and Adolf Hoffmeister—as well as several other figures with whom the Czechs collaborated, such as the Ukrainian-born, American émigré Alexander Archipenko, the Paris-based artist Ossip Zadkine, the Belgian L’Esprit nouveau editors Paul Dermée and Michel Seuphor, the Dutch De Stijl founder Theo van Doesburg, Bauhaus director Walter Gropius and instructor László Moholy-Nagy, Hungarian editor of Ma Lajos Kassák, Italian Futurist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, and, of course, Goll.

This list is a concise testament to just how interconnected these publications, their editors, and contributors were. And, printed in a bold, sans serif font, framed with solid black lines, in the style of the New Typography, and including so many of the major artists and intellectuals of the day, it brings us back to where this brief survey began. The marked internationalism and sheer number of names on this list also serves as a good reminder that the above outline of an exchange between the editors of Zenit and members of Devětsil, and the ways in which they advertised each other’s work, is but a sampling of how the interwar periodicals can be studied today to map a complex and multi-centric network across the European continent.

Published in conjunction with THE ELECTRO-LIBRARY: European Avant-Garde Magazines from the 1920s, oganized by David Senior, Bibliographer, MoMA Library, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 8, 2016–June 13, 2016.

Zenit’s first three issues highlight Expressionist tendencies, quite at odds with Teige’s own artistic affinities, but by issue four Zenit has adopted a drastically different, Constructivist style, more of a piece with later Devětsil publications.

- 1Karel Teige, “Obrazy a předobrazy” [“Images and Fore-Images”], Musaion 2 (Spring 1921): 55.

- 2Teige, “Slova, slova, slova (Part Three),” Horizont 1, no. 3 (March 1927): 47.

- 3On this subject, see Christina Kiaer, Imagine No Possessions: The Socialist Objects of Russian Constructivism (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2005).

- 4Irina Subotić, “Avant-Garde Tendencies in Yugoslavia,” Art Journal 49, no. 1 (Spring 1990): 23. Subotić writes further that is was likely Zenit’s main editor, Ljubomir Micić “who was responsible for the review’s typographical design and advertising.”

- 5Michael Cowan, “Advertising, Rhythm, and the Filmic Avant-Garde in Weimar: Guido Seeber and Julius Pinschewer’s Kipho Film,” October 131 (Winter 2010): 30.

- 6Devětsil members came into contact with a group of Yugoslav avant-gardist studying in Prague in the early 1920s. Yugoslav events and activities were even announced in the local papers, such as in the April 12, 1921, edition of the daily Čas (Time), in which a meeting of the “Czechoslovak-Yugoslavia League” at the Old Town town hall is mentioned in a listing of upcoming events. In the years 1920 to 1922, Dragan Aleksić (who also contributed to Zenit from Prague, reporting for instance on Kurt Schwitter’s form of Dada) and Poljanski hosted several Dada evenings in Prague. For more on Yugloslav Dada activities in Prague, see Holger Siegel, In unseren Seelen flattern schwarze Fahnen: Serbische Avantgarde 1918–1939 (Leipzig: Reclam-Verlag, 1992) and, in English, Jindřich Toman, “Now You See It, Now You Don’t: Dada in Czechoslovakia, with Notes on High and Low” in Crisis in the Arts, The History of Dada Vol. 4. The Eastern Dada Orbit: Russia, Georgia, Ukraine, Central Europe and Japan, ed. Stephen Foster (New York: G. K. Hall & Co., 1998): 11–39.

- 7Karel Teige to Artuš Černík, 1921, Památník národního písemnictví (PNP), Artuš Černík Archive (AČ Archive).

- 8Ibid. Teige reports that Zenit’s circulation amounts to five thousand copies within Yugoslavia, and another two to three thousand across Europe. If this truly was the circulation of Zenit, it would reflect a substantial print run, far greater (by several thousands) then any of the Devětsil periodicals.

- 9Though all Czech verse in Zenit is printed in Czech, in keeping with the magazine’s ardent internationalism, spelling errors such as those in Seifert’s poem suggest that it was for good reason that Teige had written to Černík suggesting that they send work not in Czech, but rather in German or French translation: “Definitely on account of the foreigners we have to send them our German translations and we could also dig up at least some article in French.” [Teige to Černík, 1921, PNP, AČ Archive.]

- 10As Derek Sayer has written, with City in Tears, published in 1920, “Seifert began his career.” It was dedicated to the Czech communist poet S. K. Neumann and included a preface penned by Teige that was an “uncompromising declaration” of Devětsil’s proletariat leanings. [Derek Sayer, Prague, Capital of the Twentieth Century: A Surrealist History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013): 46.] Its staunchly leftist orientation thus made it a natural choice for a review in Zenit, which had a similar political orientation.

- 11Teige to Černík, July 9, 1921, PNP, AČ Archive. Černík’s poem, “At the House of Moving Pictures,” describes the empathic experience of watching scenes from everyday life, such as lovers embracing, unfold on the screen.

- 12Subotić 21.