The performative installation Disease Thrower #5 and Circle Serpent made by Salvadoran American artist Guadalupe Maravilla, recently acquired by The Museum of Modern Art, offers a ritual space both for disease and healing. Inspired by the artist’s personal experience with migration and cancer, the work allows for a questioning of what constitutes proper care and inclusion, as well as the future of art institutions following the wake of Covid-19.

1. Entrances, exits

In fall 2019, the Museum of Modern Art acquired two works by the interdisciplinary artist Guadalupe Maravilla: Disease Thrower #5, an altar-like sculpture, and Circle Serpent, a snake-like form fashioned out of dried maguey leaves (both works were made in 2019). The objects can be shown separately or together in different configurations, but as most recently presented, Disease Thrower #5 sits within a semi-circle formed by Circle Serpent. As one installation, they mark a space charged with anticipation and suggestive of ritual.

Maravilla’s own biography dominates secondary writing about his still-evolving artistic practice; his experience both as an undocumented immigrant and with cancer are prominent themes in his art. But how might the reception of his work be expanded and changed by its new institutional context at MoMA?

In 2020, as recent debates around representation and inclusion in art institutions continue apace, the acquisition of Maravilla’s work is part of a larger effort to extend and inflect the history of Latinx art at the museum. This essay aims to illuminate the new possibilities of Maravilla’s work within the collection by countering the ways in which art by minoritarian artists may become absorbed into cultural institutions (as single works meant to stand in for entire cultural groups or art histories, or as a kind of palliative that assuages forms of historical guilt). We hope to further expand the discourse around Maravilla’s work, pointing beyond the artist’s biography toward a discussion about broader issues of medicine and healing within Maravilla’s work and the context of cultural institutions today.

Three months after the Maravilla acquisition, on March 13, MoMA closed its doors to the public indefinitely, in response to the growing threat of the COVID-19 global pandemic. The Museum, like all spaces of gathering, had become a potential vector of infection. As a result, human proximity became antithetical to well-being; shared surfaces became laced with risk. What does Maravilla’s practice, which proposes alternative modes of healing, offer for the future of the museum and beyond?

2. Host and Virus

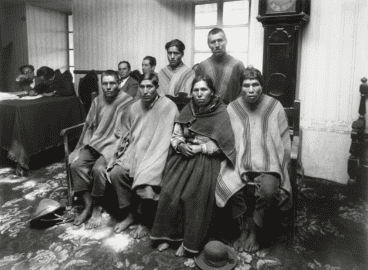

Two profound experiences shaped Guadalupe Maravilla’s life and recur as themes in his artistic practice. In 1984, at eight years old, Maravilla immigrated to the United States as an undocumented, unaccompanied child, fleeing civil war in El Salvador.1Guadalupe Maravilla, “Bio,” https://www.guadalupemaravilla.com/ Later, as an adult, he battled cancer. Maravilla was treated with radiation and chemotherapy alongside his own healing practices.

Maravilla’s installation, inspired by these experiences, poses a nonlinear and recombinant model of disease and healing through its accumulation of materials, objects, and structures with various spiritual and medicinal properties. The dried maguey leaves in Circle Serpent, the floor sculpture, are taken from the agave plant and can be eaten, used to make liquors, adapted for medicinal purposes, and even used to build roofs and make strong twine. Maravilla has inscribed them by hand with designs related to his drawing practice, which takes inspiration from Spanish colonial maps of Mexico and the Salvadoran game Tripa Chuca.2“Guadalupe Maravilla | Requiem For My Border Crossing.” Video. Whitney Museum of American Art, August 2018. https://whitney.org/watchandlisten/38966 Nestled among the leaves of the snake’s body sit bottles of Florida water, aromatic water that can be used for cleansing or spiritual healing.

Disease Thrower #5, the altar-like structure sitting within the semi-circle of the serpent’s body, adds to these traditional medicinal materials with commercial and readymade objects, including loofah sponges, plastic anatomical models, and metal ornaments. The surfaces of the work are covered with a cream-colored substance that looks like bone. These draping, petrified strands are actually made by the artist by microwaving PVA adhesive (Elmer’s® glue) and then combining them with cotton. Nestled into the altar are colorful plastic sculptures of a dissected breast and a smaller, cylindrical, colon-like sculpture, taken from commercial anatomical models that refer directly to the artist and his mother’s experiences with breast and colon cancer.

Maravilla enshrines disease and creates an altar for it. But if disease is traditionally posed as an aberration, or a battle between an organism and a foreign substance, Maravilla’s work seems to inhabit both positions at once: it creates a ritual space for disease as it invites a form of cleansing, healing, and repelling sickness—the work is, after all, a “disease thrower.”

Maravilla proposes a deep connection, possibly a causal relationship, between the trauma he experienced as a refugee and his battle with cancer. This position advances a holistic understanding of illness, in which emotional trauma and physical illness are treated as related or even as one and the same. By drawing this link, Maravilla allows us to see that both migration and disease are marked as abnormal or pathological states. In the same way that being an undocumented immigrant is marked as a deviation from the normative subject position of citizenship, being ill is marked as a deviation from the normative position of health.3On health, disease, and subjectivity, see Georges Canguilheim, The Normal and the Pathological, trans. Carolyn R. Fawcett (New York: Zone, 1989).

By adopting this position, Maravilla challenges the authority of Western medical paradigms. Borrowing the concept of sanitary citizenship from medical anthropologist Charles L. Briggs, wherein a citizen is one who fundamentally recognizes “the monopoly of the medical profession in defining modes of disease prevention and treatment,” we might understand Disease Thrower #5 and Circle Serpent as documenting the modes of illness and treatment that exist beyond the authority of the medical establishment and therefore beyond the boundaries of citizenship or society.4Charles L. Briggs, “Why Nation-States and Journalists Can’t Teach People to Be Healthy: Power and Pragmatic Miscalculation in Public Discourses on Health,” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 17, no. 3 (2003): 287–321. www.jstor.org/stable/3655387 A full discussion of sanitary citizenship can be found in Charles L. Briggs and Clara Mantini-Briggs, Stories in the Time of Cholera: Racial Profiling During a Medical Nightmare (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004). In enshrining non-traditional healing substances, like Florida water, alongside treatments like chemotherapy, referenced in the anatomical models, Maravilla proposes a new, recombinant understanding of health and disease that validates multiple systems of knowledge.

Maravilla’s alternate epistemologies now reside in the space of the Western art museum, itself traditionally conceived as an apparatus to engender citizen-subjects through cultural education and appreciation. However, since their inception, art museums have transformed and attempted to address broader and more diverse publics. In this evolving museum, Maravilla’s work offers an analogy for re-imagining the citizen-subject of the museum as one that accepts and creates multiple forms of knowledge. Perhaps Maravilla’s work suggests a sort of “un-sanitary” citizenship, following Briggs, and this unruly citizen might suggest unruly modes of viewing.

3. Vibrations and Echoes of the Object

Maravilla proposes active forms of care beyond the sculpture’s symbolic significance. Disease Thrower #5 and Circle Serpent are used as instruments in Maravilla’s sound baths and healing workshops, often organized exclusively for undocumented immigrants. The top of Disease Thrower #5 consists of a custom-made gong covered by an intricate circular weaving made of straw. The gong, even when still, serves as a visual cue for healing, where the viewer can imagine the ringing sound emitted after it is struck.

Maravilla discovered sound baths during his own battle with cancer. After finding it difficult to walk after coming out of a chemotherapy session in New York, he stumbled onto a gong sound bath by musician and healer Don Conreaux. Following a thirty-minute session, Maravilla found himself able to walk, and began training to learn about the ways in which specific sound frequencies emitted by the gongs can resonate with tendons and chakras within the body associated with trauma, movement, and anxiety. “Now that I’ve learned to heal myself, I have to teach others how to heal themselves,” Maravilla recounted in a 2019 interview.5“Guadalupe Maravilla Sound Therapy Activation.” Video. Institute of Contemporary Art Miami (ICA Miami), 2019. https://icamiami.org/channel/guadalupe-maravilla-sound-therapy-activation/. Maravilla hosted sound baths at ICA Miami and the Institute of Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University as part of his solo exhibitions at each venue.

In 2019, Maravilla hosted sound baths in which participants could spend the night in the museum while listening to a choreographed sequence of healing sounds and meditations, seeking to “cleanse latent political phobias” in audience members. To create the aural landscapes that participants hear, Maravilla uses a mallet to both strike and seemingly draw on the gong, emitting different frequencies and volumes of sound. Multidirectional and immersive, sound can be experienced communally without crowding and without touch. Perhaps forms of community and sensation that have been with us all along, such as listening, can be reimagined to accommodate a distanced and contagious world.

Upon reopening, the museum will not be the same as it was before. If large crowds to view even larger collections were once the vital signs of a healthy art system, the control of those crowds is now paramount to the safety of the museum’s visitors. What kinds of care or healing experiences might Maravilla’s work engender in the specific context of MoMA? Perhaps his project might pose a new way of thinking about the care of subjects (museum visitors) and objects (artworks).

Maravilla’s works are performative, they are hybrid object-subjects—at once sculptures, relics, performers, and catalysts. They join a conversation with other such performative objects in MoMA’s collection, like the trumpet-sculptures of Terry Adkins, or the cloth wearables of Franz Erhard Walther, or the performative installations of Senga Nengudi, all acquisitions that have entered MoMA’s collection within the past decade. These artists have not re-invented the subject nor the object; rather, they have dissolved the oppressive and artificial divisions between the two.

Such performative objects point the way toward a museum where the border between caring for subjects and objects continually disappears. Museums have never just been the stewards of objects. They have always imagined and sought to produce subjects. Over time, museums have worked not only to care for objects and envision their subject but also to care for that subject through education, engagement, and other outreach. As the pandemic transforms museums from guardians of public places into guardians of public health, the ways in which the museum provides care also transforms. Practices like Maravilla’s adapt well to these new demands. Though rich in symbolic meaning as a visual object, Disease Thrower #5 and Circle Serpent are also tools that can be deployed to provide holistic care.

4. A Serpent Eats Its Tail

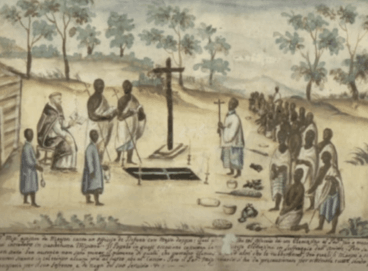

Maravilla himself offers one proposition that his childhood trauma from migration caused his cancer. Another is that his mother’s cancer signals a familial predisposition to cancer—an intergenerational occurrence of the disease. Whether or not these propositions are ultimately accurate in a scientific sense, we would argue, is irrelevant. Instead, Maravilla points us to an anachronistic understanding of illness as a phenomenon that occurs and reoccurs not only across geographies but also through time. Consider the global pandemic underlying many of the cultural histories in the Americas that Maravilla references in his sculptures—namely, the outbreaks of infectious diseases introduced by the Spanish to the New World during the 16th century colonial conquest. In a linear trajectory of human history, this violent example is one among countless pandemics that blight the timeline of human progress. Yet these events, as with all events in the past, also exist in the fugitive territory of memory. Instead of falling prey to historical amnesia, on the one hand, or assuming a linear teleology that marches inexorably forward, on the other, Maravilla’s work seems to bend time. It asks us to dwell in nonlinear histories, to explore the ways in which memory is embedded in bodies, matter, and sound.

In Disease Thrower #5, an upside-down animal mask rests at the base of the altar, as if performing its own birth from the structure. In Circle Serpent, the feathered quality of the woven maguey leaves recalls the feathered serpent central to ancient religions of Mesoamerica. Known as Quetzacoatl in the Aztec pantheon or Kukulkan to the Maya, the feathered serpent was often linked to death and rebirth, in part because of a snake’s ability to shed and regrow its skin.6For an introduction to the visual cultures of Mesoamerica, see Mary Ellen Miller, The Art of Mesoamerica: From Olmec to Aztec, 5th ed., (London: Thames & Hudson, 2018). In both pieces, the adhesive and dried leaves have already begun to show visible decay and discoloration. These forms of organic deterioration challenge the norms of museum collecting and display practice, requiring careful attention and specialized conservation techniques. The installation requires desiccants to absorb moisture and regular fumigation to ensure that the maguey leaves will last. Maravilla juxtaposes signs of vitality and healing with signs of death and illness. In this juxtaposition, a cyclical vision of those concepts emerges.

In what time do Disease Thrower #5 and Circle Serpent exist? Should we understand them as relics of Maravilla’s past performances, now archived in storage? These works sit before us in the present tense of a global pandemic and confront us with an opaque group of symbols. They promise the inevitability of illness, or trauma writ large, but still offer the possibility of healing through tokens like the Florida water. Or they may exist in the queer, abject temporality of the “not-yet-here” (following José Esteban Muñoz and Leticia Alvarado), instruments waiting for or offering the possibility of activation, signaling a present/future of both disease and healing.7See Leticia Alvarado, Abject Performances: Aesthetic Strategies in Latino Cultural Production(Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018); and José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: New York University Press, 2009). We might imagine the components of Disease Thrower #5 as a constellation of various systems of knowledge, a materialization of a posture toward healing that refuses either to villainize Western medicine or to infantilize traditional medicine. Perhaps it is all of these things at once, or never. Perhaps we will go back to normal all at once or we never will.

- 1Guadalupe Maravilla, “Bio,” https://www.guadalupemaravilla.com/

- 2“Guadalupe Maravilla | Requiem For My Border Crossing.” Video. Whitney Museum of American Art, August 2018. https://whitney.org/watchandlisten/38966

- 3On health, disease, and subjectivity, see Georges Canguilheim, The Normal and the Pathological, trans. Carolyn R. Fawcett (New York: Zone, 1989).

- 4Charles L. Briggs, “Why Nation-States and Journalists Can’t Teach People to Be Healthy: Power and Pragmatic Miscalculation in Public Discourses on Health,” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 17, no. 3 (2003): 287–321. www.jstor.org/stable/3655387 A full discussion of sanitary citizenship can be found in Charles L. Briggs and Clara Mantini-Briggs, Stories in the Time of Cholera: Racial Profiling During a Medical Nightmare (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004).

- 5“Guadalupe Maravilla Sound Therapy Activation.” Video. Institute of Contemporary Art Miami (ICA Miami), 2019. https://icamiami.org/channel/guadalupe-maravilla-sound-therapy-activation/. Maravilla hosted sound baths at ICA Miami and the Institute of Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University as part of his solo exhibitions at each venue.

- 6For an introduction to the visual cultures of Mesoamerica, see Mary Ellen Miller, The Art of Mesoamerica: From Olmec to Aztec, 5th ed., (London: Thames & Hudson, 2018).

- 7See Leticia Alvarado, Abject Performances: Aesthetic Strategies in Latino Cultural Production(Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018); and José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: New York University Press, 2009).