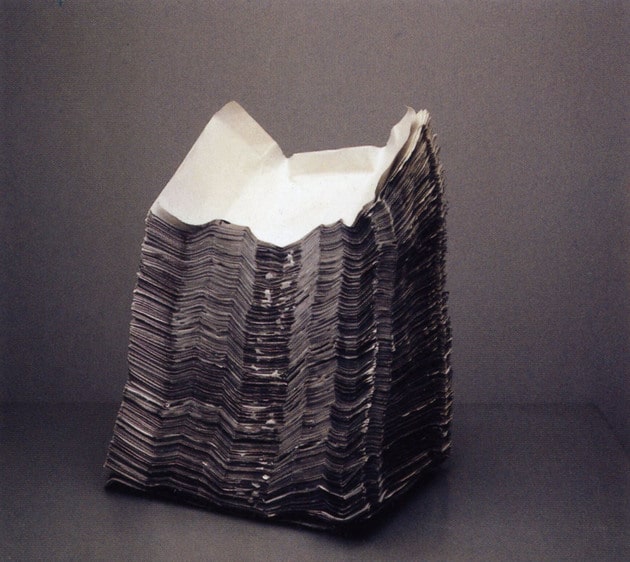

Made of 1200 cigarette packs, Jac Leirner’s Lung works both reflect the consumerism of which they are born but also transcend far beyond it while conjuring tropes from Minimalism, Conceptual Art, Pop Art as well as Neo-Concrete art of her native Brazil.

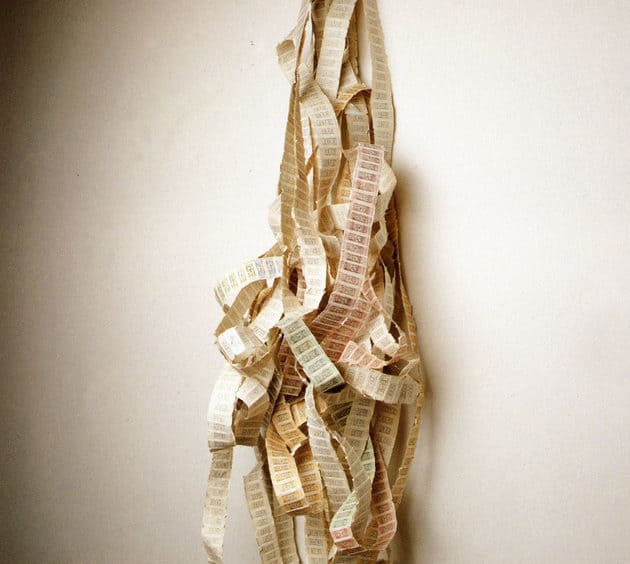

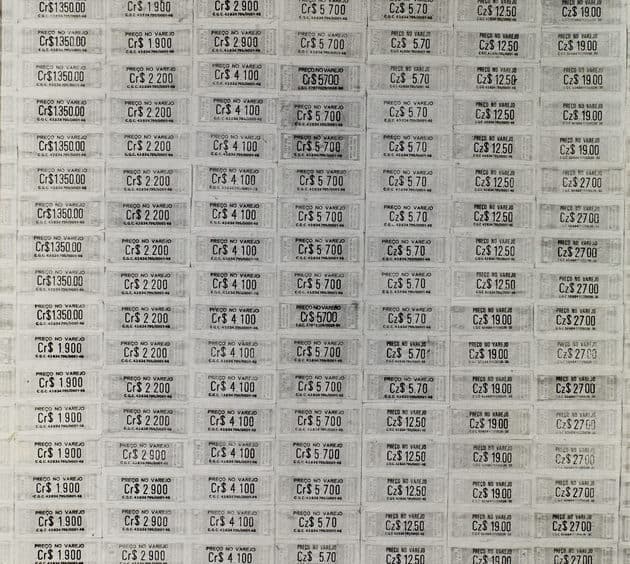

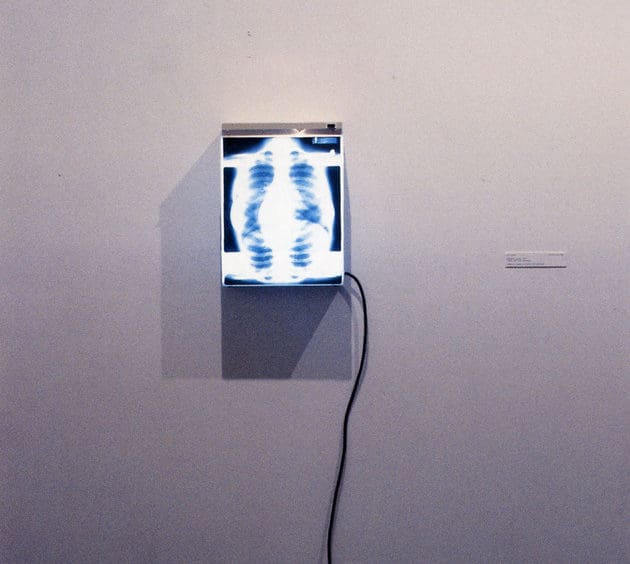

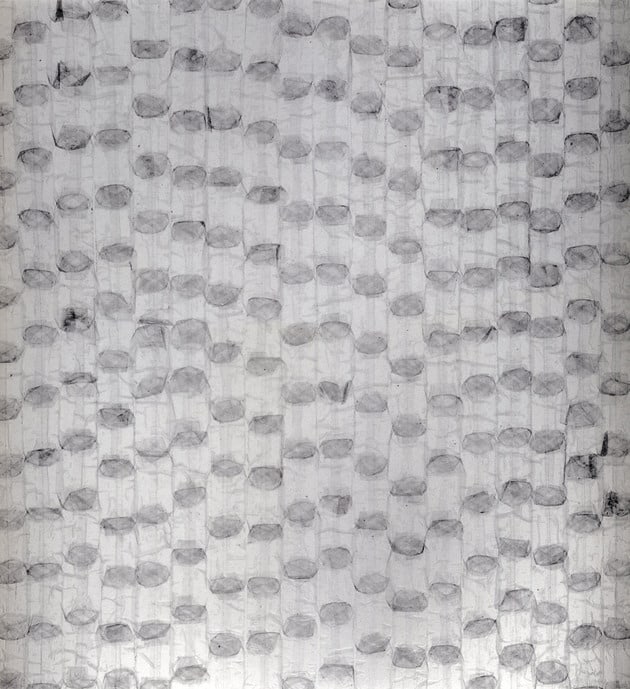

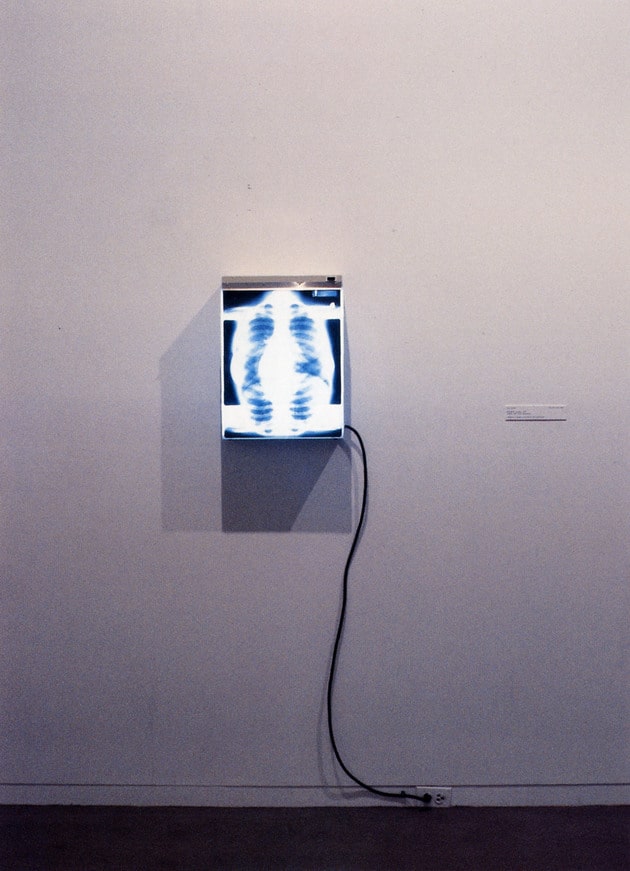

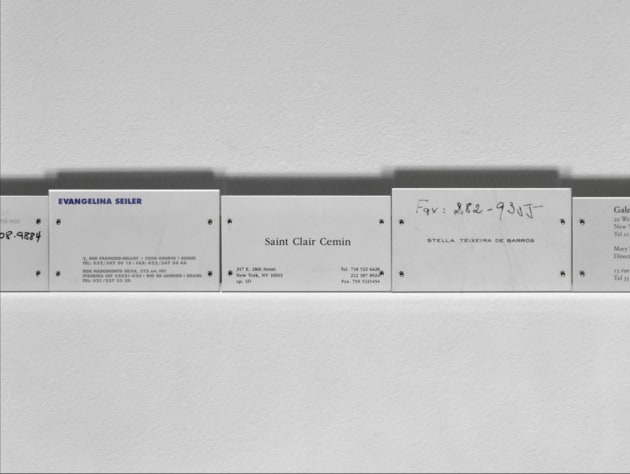

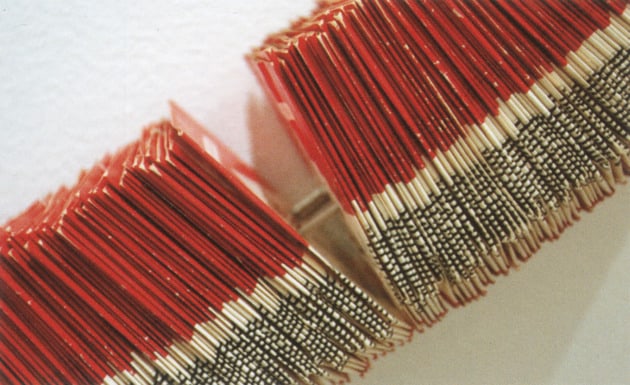

Pulmão (Lung) of 1987 is composed of eight sculptures and a multiple created from the disassembled parts of 1,200 soft packs of Marlboro cigarettes, which the artist, Jac Leirner (Brazilian, born 1961), smoked over the course of three years. MoMA’s collection holds two examples from the series: a span of precisely flattened and perforated soft packs, suspended on steel cable, which can measure from 14 1/2 feet long to more than 15 feet long, and a small plexiglass box, only 8 1/2 inches high, a multiple containing ten cellophane wrappers still flecked with bits of tobacco. Across the series, Leirner employed various techniques—knotting, sewing, gluing, folding, puncturing, overlapping, and stacking—to create pieces from her disparate materials: pull strips, price tags, laminated paper, cellophane, cigarette packs, and X-rays of her lungs. The physical qualities of the works range from the elusive heaviness of shiny and matte oblong forms to seemingly weightless transparent and translucent acrylic boxes, two-dimensional gridded assemblies, and a light box. In the largest work in the series, Marlboro’s graphic identity—the iconic red chevron atop a white carton emblazoned with a gold seal and black type—is both amplified and mutated, at once hyper-visible and illegible: a dynamic of negation in Leirner’s production noted early on by art historian Aracy Amaral but obscured in most discussions of the artist.

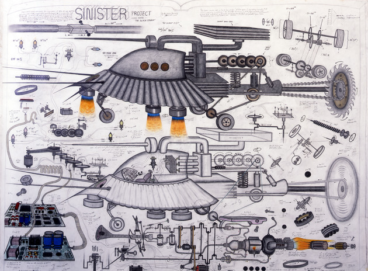

Leirner was the first Brazilian artist to rise to prominence with near simultaneity in her home country and abroad. Her best-known series—Os cem (The one hundreds) of 1986–87, Pulmão of 1987, and Nomes (Names) of 1989, as well as Corpus Delicti (1992–93) and Nice to Meet You (1997)—garnered attention in part because they demanded multiple knowledges (international and local, art historical and societal) at a moment when, as Leirner has said, the dominant artistic centers were “wanting new blood.”1As quoted in Ana Francisca Ponzio, “Arte larápia de Jac Leirner é a prova de seu delito,” O Estado de São Paulo, January 25, 1992. In each group of works, Leirner drilled down into the material conduits of distinct social habits and experiences, from the Brazilian economy’s hyperinflation of the 1980s to art-world conventions to—as in the Pulmão series—addiction and the global reach of US brands. The pieces evoke both canonical and then-newly recognized art practices—from Minimalism and Pop art to Brazilian Neo-Concretism and Conceptual art—that were fertile templates for her organization of materials culled from the refuse and other unvalued stuff of consumer society. In her accumulation of cigarette soft packs, for example, Leirner found the tense figure-ground relations of Brazilian Concrete paintings by artists such as Geraldo de Barros and Willys de Castro while evoking the slumping forms of Robert Morris and the serial commercial identities of Andy Warhol.

Leirner was born to a family deeply involved in the art world (her parents, Adolpho and Fúlvia Leirner, are prominent collectors of postwar Brazilian abstraction). As a student at the private São Paulo university Fundação Armando Álvares Penteado (FAAP) from 1979 to 1984, her professors were renowned artists, educators, and thinkers, and she and her classmates—including Leda Catunda and José Leonilson—would go on to be among the most visible and best-regarded artists of their generation. In the 1970s and early 1980s, Nelson Leirner (the artist’s uncle), Julio Plaza, Regina Silveira, and Walter Zanini reformed FAAP’s curriculum, increasing the rigor of the technical and theoretical training and introducing first-year courses modeled on the Bauhaus preliminary course. That cornerstone of Bauhaus pedagogy made the experiential and abstract study of color, form, texture, and materials the foundation of visual expression. The emphasis on experimentation and an in-depth knowledge of materials would shape Leirner’s conceptual and technical approach. Her study of foreign languages, interest in poetry and music, and month-long trips to New York and Europe—and frequent hemispheric and transatlantic travel after graduating—contributed to a multilingual historiographic artistic practice.

Through analysis of the shifting titling of the Pulmão series, the stakes of Leirner’s production come into new focus, distanced from the sometimes self-congratulatory rhetoric with which US and European institutions in the early 1990s trumpeted a globalizing art world and Latin American art—positions that find echoes today. When MoMA acquired two Pulmão works in 1991, Leirner opted for the English-language title Lung and removed the subtitle she originally assigned to the larger work: Plumária, às duras penas. (Plumária refers to indigenous Brazilian featherwork, and a duras penas is an expression meaning “with difficulty,” though pena can also mean “feather” and dura pena can be translated as “hard feather.” There is also the alliteration, and euphony, of pulmão and plumária, and the evocation of plumage as a lens to understand the sculpture.)

At the time, Leirner said the change was due to the subtitle’s untranslatability and orientation toward a domestic Portuguese-speaking audience, and has since shared that she thought the subtitle foolish—a joke that fell flat. I am not suggesting the subtitle be resuscitated—the English-language title Leirner adopted is consistent with her generative embrace of English, French, and Portuguese words and their combinations in her production as a whole—but the issue of untranslatability provides a necessary pause. Are there facets of Pulmão/Lung unaccounted for in the social, formal, historiographic, and pedagogical narratives traced above?

Plumária, às duras penas points to other transformations—the bombardment of advertising language and consumer products become hard feathers, or the material culture of late capitalist civilization—and conjures a bodily adornment composed of the detritus of addictive consumption. Neither a celebration nor a condemnation, the work, for all its societal knowledge, formal beauty, and art-historical intelligence, hangs on the wall in tension, with difficulty. Leirner has said that “what I do in all the works is to create a place for things that don’t have one.”2As quoted in Jac Leirner in Conversation with/en conversación con Adele Nelson (New York: Fundación Cisneros, 2011), 54. The places she fashions are marked by the friction of translation, by an addition that also negates. Leirner’s turning over of things in her hands—and mind, and tongue—and her laborious care for the materiality and rituals of consumption create encounters that oscillate between humor and sobriety, homage and fever dream, taxonomy and eschatology.

- 1As quoted in Ana Francisca Ponzio, “Arte larápia de Jac Leirner é a prova de seu delito,” O Estado de São Paulo, January 25, 1992.

- 2As quoted in Jac Leirner in Conversation with/en conversación con Adele Nelson (New York: Fundación Cisneros, 2011), 54.