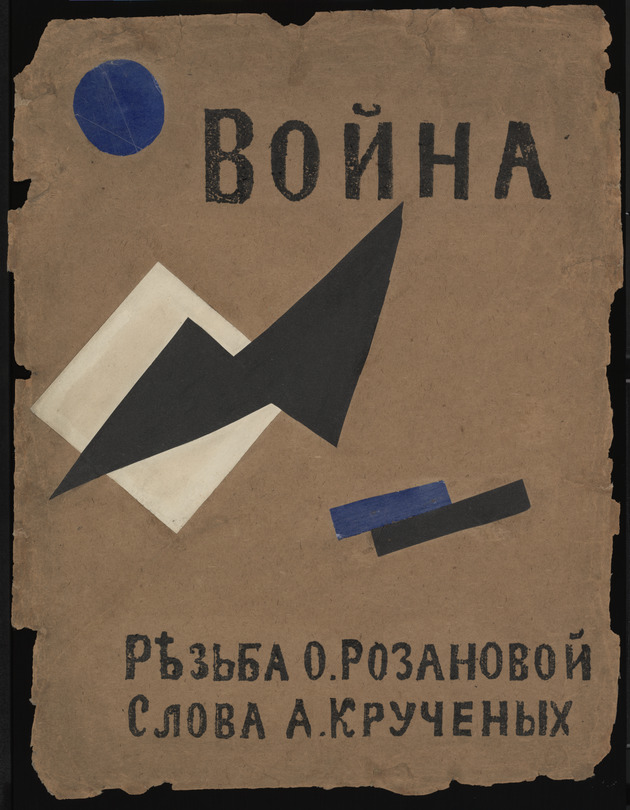

The 1916 album War by Olga Rozanova, made in collaboration with Aleksei Kruchenykh, draws upon the visual and linguistic vocabularies of Futurism and Suprematism to explore the trauma of war.

The album War was created by the Russian avant-garde artist Olga Rozanova (1886–1918) with the poet Aleksei Kruchenykh (1886–1968) at the onset of World War I.1This essay is related to my article “Civilians Seeing the War: Olga Rozanova and Aleksei Kruchenykh’s 1916 War,” in Artistic Expressions and the Great War: A Hundred Years On, ed. Sally D. Charnow (Bern: Peter Lang, forthcoming [2020]). Between 1914 and 1915, Rozanova worked on the album in her hometown of Vladimir, a city located east of Moscow, while Kruchenykh composed the verses in the Caucasus during a deferment from military service.2Kruchenykh would later fulfill his military duties as a draftsman for the Erzurum railway in Sarikamish (today, Sarıkamış in Turkey’s Eastern Anatolia region) in April 1916. Published in early 1916 in Petrograd, the album contains a letterpress–printed table of contents, fifteen sheets of linocut Cubo-Futurist illustrations, Suprematist collages, and poems in the transrational language of zaum’ (a neologism meaning “beyond the mind”).3See Gerald Janecek, Zaum: The Transrational Poetry of Russian Futurism (San Diego: San Diego State University Press, 1996). Inside War, images of harrowing battle scenes, cannonballs being barreled into cities, soldiers being pierced by bayonets, and free-falling airplanes alternate with poems that fire a barrage of unorthodox language, syntax, and semantics unique to Russian Futurist verse from anthropomorphized battlefields.

Rozanova and Kruchenykh met in 1912 and began collaborating the following year with various artists and poets including, among others, Kazimir Malevich, Mikhail Larionov, Natalia Goncharova, and Velimir Khlebnikov, producing nearly a dozen illustrated books and albums not long before they worked exclusively with each other.4The genre of the illustrated book has been the subject of a breadth of scholarship. See, for example, Susan P. Compton, The World Backwards: Russian Futurist Books, 1912–16 (London: British Library, 1978); Margit Rowell and Deborah Wye, The Russian Avant-Garde Book, 1910–1934 (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2002); and Nancy Perloff, Explodity: Sound, Image, and Word in Russian Futurist Book Art (Los Angeles: The Getty Research Institute, 2016). Their collaboration stood the test of war as they worked separately and remotely on the album by exchanging letters with each other as well as with the financier of the album and noted proponent of Futurist books, Andrei Shemshurin. The artist-poet duo, whose creative and romantic partnership continued until Rozanova’s death from diphtheria in 1918, tell the story of war that is simultaneously imagined and real, mythical and historical. More than a denunciation or celebration of war, the album is an exploration of war when it is agonizingly present and yet also distant, for the artist and poet living away from the frontlines.

War combines collage elements with linocuts made using sheets of mass–produced linoleum flooring, adopted by artists as an alternative to traditional methods of printmaking, and printed in red, green, and black ink. The album’s frontispiece shows an unfurled banner with the word voina, Russian for “war,” hovering above a triumphant woman brandishing a sword and trumpet (figs. 1–2). This call to war conjures mythic and modern visuals and semi-scrutable verses meditating upon the cataclysmic forces of modern war technology that is to come in the album. With its small distribution of one hundred copies (two of which are in MoMA’s collection), the album likely reached a close-knit audience of artists, poets, and collectors, which lends itself to an intimate affect. At the same time, as a work of art that combines the separate arts of printmaking, collage, and poetry into a unified whole, it embodies the Wagnerian notion of Gesamtkunstwerk, or a total work of art. The album’s interplay between media, it can be said, presages the multimedia print publications incorporating photomontage and photomechanical reproductions that flourished in the wake of the 1917 Russian Revolution in the Soviet Union and abroad. Out of this synthesis of the arts, the album’s iconography and style further contribute to another totality known as “total war.” A concept that gained popularity during World War I, “total war” was understood as mobilizing all aspects of society to partake in the war effort. In effect, the war unsettled the emotional distance between home and frontline, combatant and civilian, to produce what literary scholar Mary Favret describes as “wartime affect.”5In such a zone, war is ongoing, distant, and present yet absent, creating what Favret describes as “the complex working of time-consciousness and feeling that accompanies and shapes the awareness—but also the unknown-ness—of modern, distant war.” See Mary A. Favret, War at a Distance: Romanticism and the Making of Modern Wartime (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), 1, 12. Such affect can be observed in the letters exchanged by the artists and their relatives and colleagues. In one letter addressed to Kruchenykh, Rozanova anguishes over the possibility that his position on standby could change into ready reserve, catapulting him to the frontlines.6Olga Rozanova to Aleksei Kruchenykh, October 1914, quoted and translated in Nina Gurianova, Exploring Color: Olga Rozanova and the Early Russian Avant-Garde, 1910–1918, trans. Charles Rougle (Amsterdam: G+B Arts International, 2000), 74. Such documents reveal that their wartime experiences fell several removes from the frontlines, rendering the couple physically far but psychologically close to the conflict.7At the outbreak of the war, Rozanova contributed fashion and textile designs to the war-relief exhibition Women Artists for the Victims of War, held in Moscow in December 1914–January 1915. See Natalia Y. Budanova, “‘Women Artists to Victims of War’—The First Exhibition of the Moscow Union of Women Painters and its Reception by the Contemporary Press,” Artl@s Bulletin 8, no. 1 (2019): 108–23.

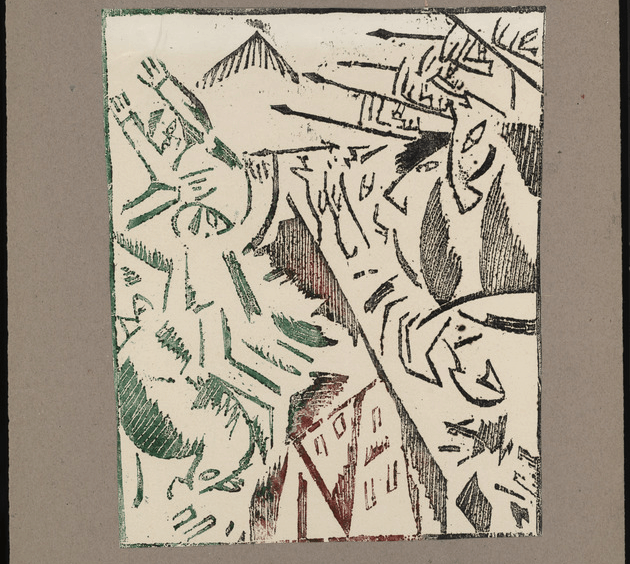

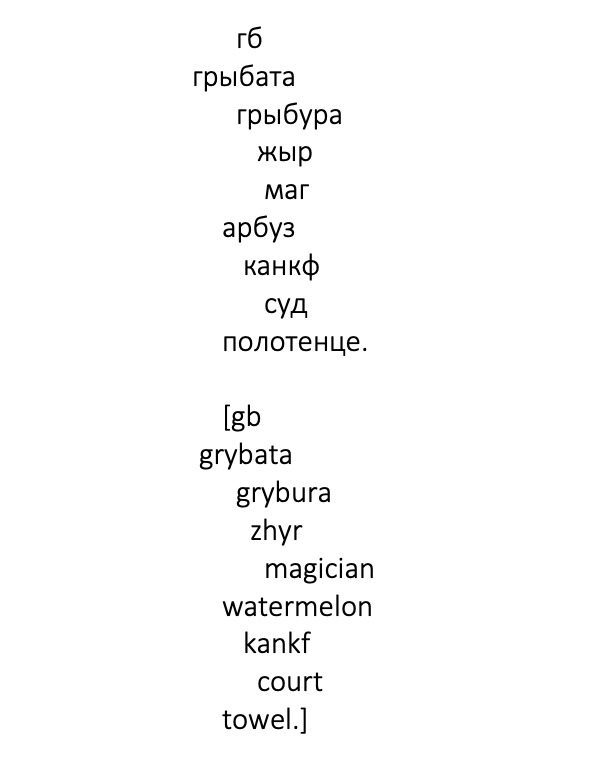

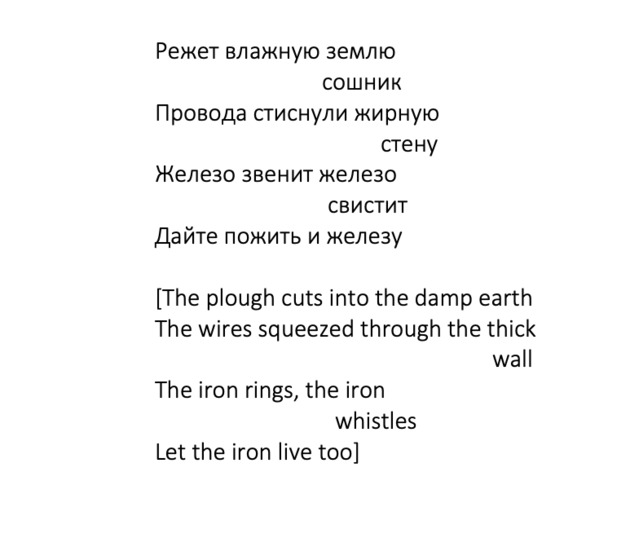

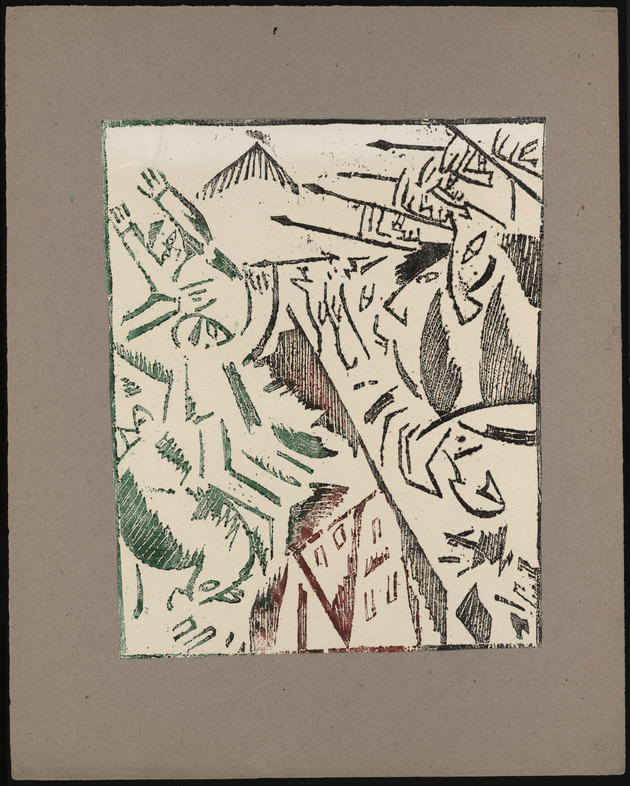

Following the call to war, civilian spaces are rendered fair game in Destruction of the City (fig. 3) as cannonballs level buildings in an unidentified city. Similarly, the collage Airplanes over the City (fig. 4) depicts fatal clashes, in linocuts, of propellers, airplanes, and a body with shrapnel-like shapes cut from paper and glued to the sheet. In these figurative and abstract forms, Rozanova may be seen as negotiating the means of representation when one bears witness to the traumas of war. During the production of the album, Rozanova experimented with a nonobjective idiom of painting and contributed work to the landmark 0.10 (Zero-Ten): The Last Futurist Exhibition of Painting in Petrograd in December 1915.8For Rozanova’s relationship to Futurism, see Christina Lodder, “Olga Rozanova: A True Futurist,” in International Yearbook of Futurism Studies, vol. 5, Special Issue: Women Artists and Futurism, ed. Günter Berghaus (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2015), 199–225. The search for a visual form to communicate the horrors of war is matched in an alliterative onslaught of abstracted verses in Kruchenykh’s “Jump from an Airplane:”

The poem combines fragments stemming from the Russian words gryzt’ (to gnaw or devour) and batalon (battalion) in an attempt to construct a new language to describe the nature of war.9Unless otherwise noted, all translations are my own. The irregular spacing of one line advancing and another one retreating further evokes the movement of a battalion on the frontlines.

In another poem that diverges from the indeterminate zaum’ verses, Kruchenykh delivers a cacophony emerging from the battlefield using conventional Russian:

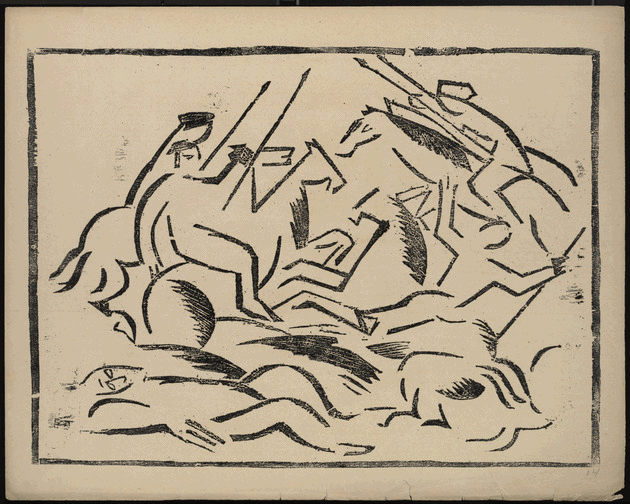

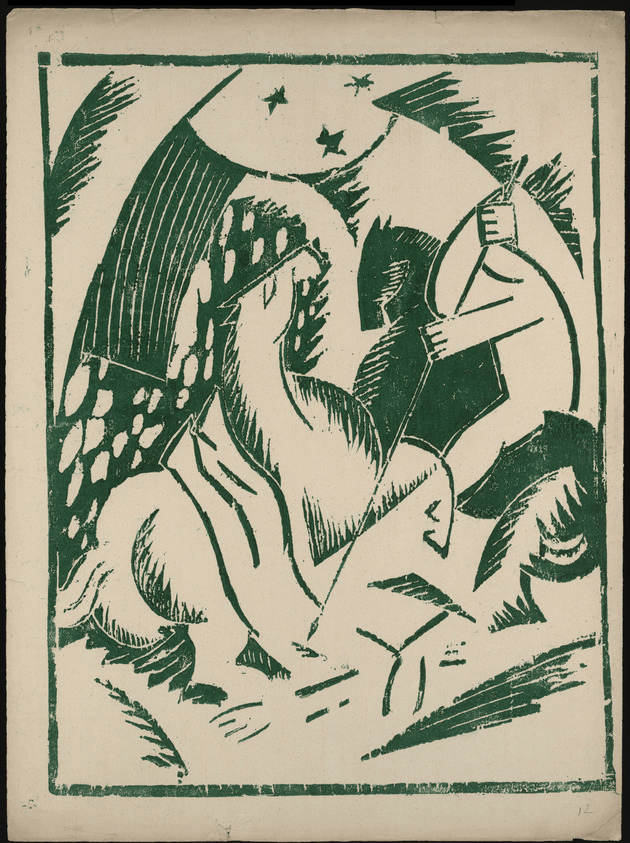

Through the alliteration of Russian consonants, the poet anthropomorphizes iron, which played a major role in the production of weapons during the war, as offering a plea for life. The scabrous green lettering in the linocut further enhances the sonic effects of the verses and evokes script styles found in Russian woodcuts known as lubki or, the singular, lubok (fig. 5). While the illustrations and poems alternate in a rhythmic pace—with several verses printed in the table of contents—two sheets include text that Kruchenykh extracted from a newspaper bulletin that Rozanova then rendered in the illustrations (fig. 6). One of these sheets contains an image of a German soldier stabbing an opponent with a bayonet while the text reads: “With horror he recalls personally witnessing those crucified upside down by Germans.” In addition to references to the unfolding war, Rozanova intersperses classical motifs throughout the album, such as the horse and rider, which symbolize an aesthetic and spiritual confrontation, appearing in the illustrations of fallen equestrians in Battle, a transcendent face-off between fighters on rearing horses in Duel, and bayonet-wielding equestrians charging at helpless figures in Combat in the City (figs. 7–9).

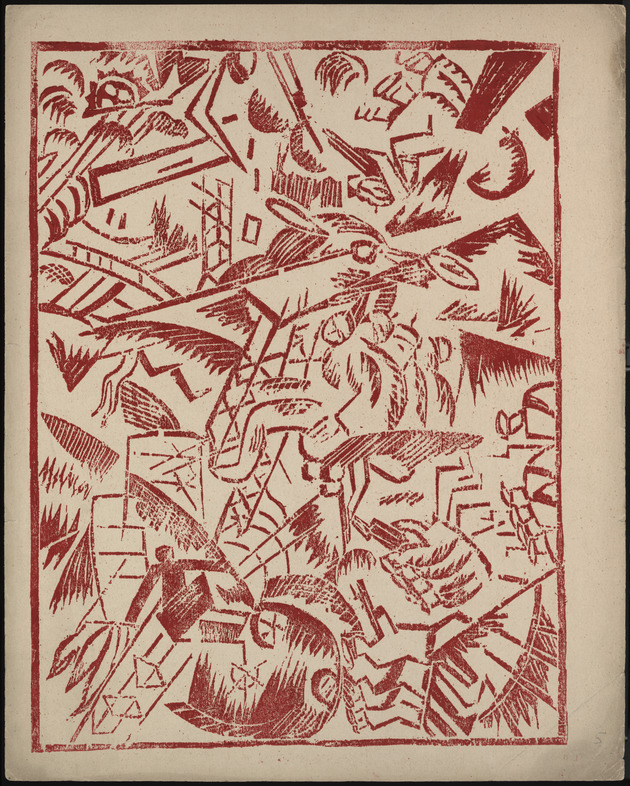

Such spectacular, if not sublime, visuals of battle rooted in both a mythical and historical moment, along with the anthropomorphized battlefields in Kruchenykh’s verses erupt across the album’s final illustration, titled Battle in Three Spheres (Land, Sea, and Air) (fig. 10). The red outlines of man, machine, and nature collide into one totality that creates, perhaps, the clearest visualization of “total war.” Here, the boundaries of figures with weapons, the propellers and wings of aircrafts, a stylized sun and smoke clouds are brought into a fractured whole. The echoes of the trumpet pressed against the lips of the powerful female warrior from the beginning of the album comes full circle via its sounds reverberating across land, sea, and sky with a resounding quandary. Do we heed the call of the trumpet to pause or do we take irreparable action with the sword? The album emerges as an unconventional war story of those living through but away from war, told with varying degrees of proximity to the violence of the frontlines.

- 1This essay is related to my article “Civilians Seeing the War: Olga Rozanova and Aleksei Kruchenykh’s 1916 War,” in Artistic Expressions and the Great War: A Hundred Years On, ed. Sally D. Charnow (Bern: Peter Lang, forthcoming [2020]).

- 2Kruchenykh would later fulfill his military duties as a draftsman for the Erzurum railway in Sarikamish (today, Sarıkamış in Turkey’s Eastern Anatolia region) in April 1916.

- 3See Gerald Janecek, Zaum: The Transrational Poetry of Russian Futurism (San Diego: San Diego State University Press, 1996).

- 4The genre of the illustrated book has been the subject of a breadth of scholarship. See, for example, Susan P. Compton, The World Backwards: Russian Futurist Books, 1912–16 (London: British Library, 1978); Margit Rowell and Deborah Wye, The Russian Avant-Garde Book, 1910–1934 (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2002); and Nancy Perloff, Explodity: Sound, Image, and Word in Russian Futurist Book Art (Los Angeles: The Getty Research Institute, 2016).

- 5In such a zone, war is ongoing, distant, and present yet absent, creating what Favret describes as “the complex working of time-consciousness and feeling that accompanies and shapes the awareness—but also the unknown-ness—of modern, distant war.” See Mary A. Favret, War at a Distance: Romanticism and the Making of Modern Wartime (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), 1, 12.

- 6Olga Rozanova to Aleksei Kruchenykh, October 1914, quoted and translated in Nina Gurianova, Exploring Color: Olga Rozanova and the Early Russian Avant-Garde, 1910–1918, trans. Charles Rougle (Amsterdam: G+B Arts International, 2000), 74.

- 7At the outbreak of the war, Rozanova contributed fashion and textile designs to the war-relief exhibition Women Artists for the Victims of War, held in Moscow in December 1914–January 1915. See Natalia Y. Budanova, “‘Women Artists to Victims of War’—The First Exhibition of the Moscow Union of Women Painters and its Reception by the Contemporary Press,” Artl@s Bulletin 8, no. 1 (2019): 108–23.

- 8For Rozanova’s relationship to Futurism, see Christina Lodder, “Olga Rozanova: A True Futurist,” in International Yearbook of Futurism Studies, vol. 5, Special Issue: Women Artists and Futurism, ed. Günter Berghaus (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2015), 199–225.

- 9Unless otherwise noted, all translations are my own.