Shot in 1970 in Mangue, Rio de Janeiro’s poorest red-light district, and the city’s financial district, Neville D’Almeida’s Mangue-Bangue, presents a portrait of the “normality” of marginalized and criminalized bodies during Brazil’s military dictatorship. Introducing humorous or odd figures in place of the heroic, revolutionary male protagonist and confronting the spectator with explicit scenes of genitalia, defecation, and drug use, the film was never released upon completion due to the explicit nature of its content and disappeared for several decades until it reappeared in the Collection of MoMA in 2006.

Reflecting on the making of Mangue-Bangue almost forty years after its first screening in New York in 1973, the Brazilian director Neville D’Almeida remarked, “I wanted to make a film with all those things I had never seen in cinema before.”Neville D’Almeida: “Eu queria colocar no cinema as coisas 1que eu nunca vi no cinema.” Translation by author. Neville D’Almeida, interview with author, Berlinale 2013, 63rd Berlin International Film Festival, February 8, 2013. Within the context of the Berlinale, I co-curated a Forum Expanded section focused on the Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica. As part of this program, I organized a panel discussion with D’Almeida, a screening of some of Oiticica’s Super 8 films, and exhibitions of Oiticica’s Block-Experiments in Cosmococa—Program in Progress: CC4 Nocagions at Liquidrom (in collaboration with D’Almeida) and CC6 Coke Head’s Soup (in collaboration with Thomas Valentin). Mangue-Bangue was presented on the occasion of the exhibition Cosmococa at Berlin’s Dickinson Gallery in February 2013. I recorded several conversations with D’Almeida in Berlin in early 2013, and on Ilha da Gigóia in Rio de Janeiro in February and March. I have titled these recordings “The Neville Tapes,” and they await thorough editing and publication. Neville D’Almeida and Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz, “The Neville Tapes,” Berlin and Rio de Janeiro, 2013, personal archive of author. By that he meant, among other things, a stock exchange broker shoving a finger up his own ass and then smelling it, and rubbing off the waxy secretion under his prepuce so he could taste it; a sex worker carefully crushing amphetamine pills, and then preparing, cooking, and shooting them up before attending the next client; or D’Almeida himself peeing in the shower. Mangue-Bangue is uncompromisingly radical and, at the same time, a fascinatingly banal film: it is cinematographic evidence of life itself. And nothing less than life itself was at stake between 1968 and 1972, when Brazilian society was living through the harshest moments of a military dictatorship.2Similar to many other South American countries during the post–World War II period and after the Cuban Revolution of 1959, Brazil suffered a US-backed coup d’etat. In 1964, the Brazilian military staged a coup against the leftist president João Goulart, who was forced to resign and go into exile. The military dictatorship lasted more than 20 years, until 1985. The years between 1968 and 1972 were marked by the violent enforcement of AI-5, which stripped citizens of their basic civil rights and led to severe persecution and execution of members of the political opposition. At that time, many important figures in Brazil’s countercultural movement, including Hélio Oiticica, Gilberto Gil, Caetano Veloso, Jorge Mautner, Helena Ignez, Rogério Sganzerla, and Neville D’Almeida, fled to London, New York, and other cities.

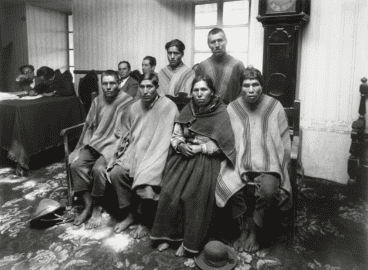

Filmed in 1970 in both Mangue, Rio de Janeiro’s poorest red-light district, and the city’s financial district, Mangue-Bangue presents a portrait of the “normality” of marginalized and criminalized bodies during the state of exception imposed by the military regime. Highlighting the severe contrast between these neighboring zones within Rio’s center, Mangue-Bangue mirrors the vertiginous encounter between nascent finance capitalism and the temporalities and crude materiality of work and desire that build the inextricable fabric of everyday life in a tropical metropolis on the verge of collapse. The cast includes actress Maria Gladys, notorious for her expressive body performances, and actor Paulo Villaça, who gained fame for his role as the protagonist in Rogério Sganzerla’s O Bandido da Luz Vermelha in 1968.3Villaça would later reappear in A Dama do Lotaçao (Lady on the Bus, 1978) and Rio Babilônia (1982), two of D’Almeida’s most successful films. Both performances build the link between D’Almeida’s film and the work of the Cinema Marginal, a small group of avant-garde filmmakers and actors who defied censorship and repression under the military regime. Mangue-Bangue is distinctive, however, because it features some hitherto unseen figures in Rio’s underground, including the legendary Jimi Hendrix impersonator Damião Experiença, and the transgendered women living and working in a red-light établissement in Mangue that is managed by Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica’s friend Rose Matos—famous for her samba dancing skills and for being the daughter of the influential Oto do Pó (“Powder Oto”), an informal authority on the favela of Mangueria.

In contrast to the intellectual filmmakers of the 1960 and ’70s, such as Glauber Rocha or Rogério Sganzerla, who publicly fought amongst themselves in cultural magazines and newspapers for the throne of Brazilian avant-garde cinema, D’Almeida pushed the limits of what were the established codes of the avant-garde’s symbolic economy. Flirting with the dogmatic approaches of a political-author cinema, he would frequently undermine the seriousness of their so-called Cinema Novo style by, on the one hand, caricaturizing its pamphleteerism (for example by introducing humorous or odd figures in place of the heroic, revolutionary male protagonist) and, on the other, by confronting the spectator with explicit scenes of sex, defecation, and drug use. By portraying the sheer banality of the everyday, D’Almeida rendered the trash aesthetics of the Cinema Marginal almost mannerist or pretentious: in Mangue-Bangue we’re not simply confronted with an outlaw aesthetic, but rather with real drugs, real feces, and real genitals. As D’Almeida put it, Mangue-Bangue was all about “producing evidence against oneself.”4D’Almeida and Cruz, “The Neville Tapes.”

Toward 1978, with A Dama do Lotaçao (Lady on the Bus, 1978)—a film about a rich, newly married young woman seeking sexual escapades along the routes of Rio de Janeiro’s public transportation system—D’Almeida’s cinema became literally promiscuous. At the end of the 1970s, no other Brazilian filmmaker was more commercially successful—or more censored. D’Almeida’s first two feature films, Jardim de Guerra (War Garden, 1967) and Piranhas do Asfalto (Pavement Whores, 1970), were suppressed by the military regime, intersected, and partially lost forever, while Mangue-Bangue would disappear for decades.5Neville D’Almeida, Além Cinema (Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Cultural Oi Futuro, 2011), published on the occasion of D’Almeida’s 2011 solo exhibition at Oi Futuro Flamengo, besides containing a full filmography with accompanying texts and interviews, includes a fascinating collection of legal documents tracing the history of censorship in the director’s career. At the same time, A Dama do Lotação was the biggest box-office success of its time, and the director’s next films, Os Sete Gatinhos (The Seven Kittens, 1980) and Rio Babilônia (Rio Babylon, 1982), would be widely acclaimed, establishing him as one of the most important Brazilian filmmakers of his generation.6A Dama do Lotaçao (Lady on the Bus, 1978), based on a play by Nelson Rodriguez, had approximately 6.5 million viewers nationwide, a national box-office record that was only topped more than 30 years later, in 2010, by José Padilha’s Tropa de Elite 2.

Mangue-Bangue, perhaps D’Almeida’s most experimental film, is certainly the opposite of what one would expect from a box-office champion. It was shot without sound, and in a sequence of long takes that challenge the spectator’s durational experience.7Shortly after he finished shooting the film, in 1970, D’Almeida fled Brazil with the original footage and went to London, where he edited the film without sound. A soundtrack was posthumously produced. The film was later assembled as loosely scattered scenes, thwarted by recurring images of a cock fight, and scenes that point to the only narrative thread in the film: the story of a stock exchange broker who, caught up in the dizziness of financial speculation, loses his bearings and gradually regresses into a primate, raving and ambulating through the neighboring financial district, rolling through muddy streets, losing his clothes piece by piece and eventually, once naked, defecating in front of the camera and then disappearing into the jungle.8In Rio de Janeiro, amid the heart of the urban landscape, one encounters parts of the jungle—branches that have crept in, little tropical islands with waterfalls, toucans, monkeys, and opossums.

Throughout this rudimentary narrative, the film shows the normality of Mangue’s female, male, and trans sex workers—who are depicted doing laundry or drugs, or waiting for clients—“not in order to exploit this visually, but rather to capture the dignity of these rituals of misery,” as the filmmaker puts it.9D’Almeida and Cruz, “The Neville Tapes.” With a calm hand and steady eye, D’Almeida portrays the routines of daily life—their pulse and pace, their movements and gestures—in what might seem, to most arthouse audiences, like an abnormal situation or, at least, a highly precarious one. This is contrasted with the triviality of the hygiene rituals of middle-class bohemian white people—who are shown cleaning themselves and engaging in all sorts of other everyday activities, such as hanging out, smoking pot, and listening to music. Most of the scenes in Mangue-Bangue are colored by a fascinating mixture of boredom and beauty, the “cinematic pleasure” of what Oiticica calls “non-situations,”10See Hélio Oiticica, “Mangue-Bangue,” in Além Cinema, by D’Almeida, 111–12. or in a seemingly suspended state of exception, framed by the structural violence and social inequality of life under a military regime.

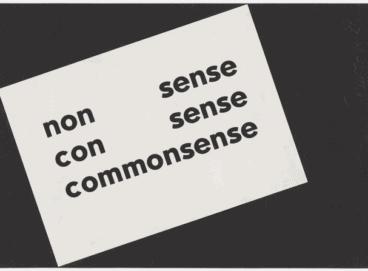

Later Oititica would conjugate the term “non-situations,” referring to them as a “non-narrations” or “mosaics” of the “limit-situations” of everyday life. According to Oiticica, Mangue-Bangue cannot be understood as a consolidated work of cinema, but rather as a negation, or a “mosaic-fragment” that follows a horizontal logic and opposes the edification of those totems of the avant-garde, the self-glorifying “GODARD/PICASSO/STRAVINSKY.” He writes, “MANGUE BANGUE should not be considered then, from the point of view which expects it to propose ‘a search for a new form of cinema,’ or as a simple metacritique of the actual one . . . not as expression which is an end-in-itself . . . but as an instrument of open experimentation freed from the heaviness of the category of art.”11See Oiticica “Mangue Bangue.” Capitalization follows original. As he describes it, Mangue-Bangue is the opposite of the fulfilled development of an avant-garde art work; it is the work as a state of crisis; it is a negation that “a superior vital necessity commanded.”12Ibid.

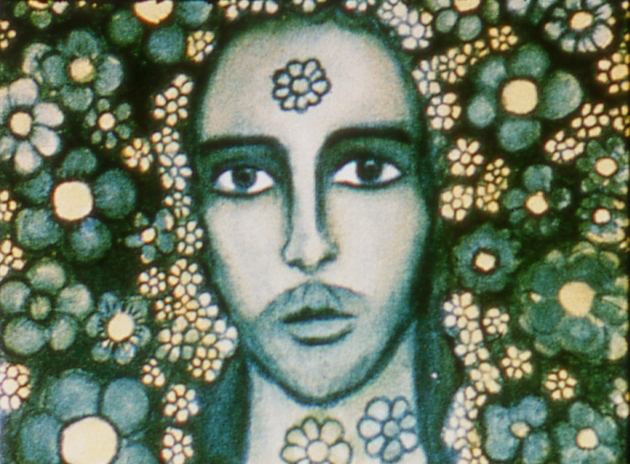

Oiticica continues, “NEVILLE’s concern is to grasp environments’ sensorial plasticity,” and his camera work acts as “a sensorial glove for touching-probing-circulating.”13See Hélio Oiticica, “Block-Experiments in Cosmococa—Program in Progress,” in Hélio Oiticica: Quasi-Cinemas, ed. Carlos Basualdo, exh. cat. (Cologne, Germany: Kölnisher Kunstverein; New York: New Museum of Contemporary Art; Columbus, Ohio: Wexner Center for the Arts; Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany, in association with Hatje Cantz, 2002), 98–101. Capitalization follows original. This “sensorial plasticity” is underscored by the scarcity of sound, with silent scenes overdubbed and long sequences left in absolute silence, making the body performances of the actors extraordinarily palpable in their presence and physicality. As Oiticica put it, “It pulses with pictorial sensuality (feel the color) and fragments into geometrically set episodes within its editing structure as if it were a cartoon strip made into sequence.”14Ibid., 97 He summarizes the aesthetic work of Mangue-Bangue, in his own particular way, as “tactile-vision microplaying manguemolecules . . . montage cut dislocated takes the end of the concept of cinema verité since CINEMA IS THE TRUTH and not representation of truth, what is the truth, anyway? BULLSHIT.”15See Oiticica “Mangue Bangue,” 111. Capitalization follows original.

Contradictions

There are two contrasting ways to understand the historicity of Mangue-Banguetoday: on the one hand, there is the history of its absence, and on the other, the history of its presence. Mangue-Bangue had been a myth, a rumor, a sort of foundational legend for a tropical cinéma maudit—an accursed cinema outside of social norms and legality—until 2006, when it was rediscovered by Brazilian researcher Fred Coelho in the film archives of The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).16On the discovery of Mangue-Bangue in English, see Frederico Oliveira Coelho, “The Rediscovery of Mangue-Bangue,” in Além Cinema, by D’Almeida, 108–10; in Portuguese, see http://objetosimobjetonao.blogspot.com/2009/07/mangue-bangue.html. For Coelho’s outstanding research on Hélio Oiticica’s New York period, see F. Coelho, Livro ou livro-me: os escritos babilônicos de Hélio Oiticica (1971–1978) (Rio de Janeiro: EDUERJ, 2010). Even if only a handful of people actually saw the film before it disappeared, historically, it must be understood as the seed for an epoch-making innovation in Brazil’s avant-garde cinema of the 1960s and ’70s, which Oiticica would baptize “quasi-cinemas.”17“Quasi-cinemas” was the term coined by Oiticica to refer to a series of cinematic environments or installations that, made during his stay in New York City, combined film and slide projections with music and hammocks in order to immerse the viewer in multisensory experiences. For more information on the notion of “quasi-cinema,” see Basualdo, Hélio Oiticica: Quasi-Cinemas. Mangue-Bangue, in fact D’Almeida’s third full-length film, is the formal precursor of D’Almeida and Oiticica’s famous (and infamous) Block-Experiments in Cosmococa—Program in Progress, made in New York in 1973–74.

Mangue-Bangue, the first collaboration between D’Almeida and Oiticica, was conceived in 1968–69, but the film was ultimately shot by D’Almeida alone in Rio, while Oiticica moved from London to New York in 1970 after receiving a Guggenheim grant. Mangue-Bangue was shown for the first time in 1973 at a small screening organized by Oiticica at MoMA with a handpicked audience that included some of the most important Brazilian artists and thinkers living in political exile at the time, including Haroldo de Campos, Quentin Fiore, and Oiticica himself, as well as some US avant-garde artists. This would be the only known screening before the film reappeared in 2006.

Today D’Almeida and Oiticica’s Cosmococa collaborations, a series of installations featuring hammocks, mattresses, and other leisure facilities, slideshows of images that are laced with carefully arranged cocaine powder and accompanied by avant-garde, rock, pop, and Brazilian folk music, or the sounds of the queer New York underground of the time, can easily be regarded as the most celebrated Brazilian contribution to twentieth-century avant-garde experiments on the threshold of art and cinema.18For more on the Cosmococas, see Sabeth Buchmann and Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz, Hélio Oiticica and Neville D’Almeida: Block-Experiments in Cosmococa—Program in Progress (London: Afterall; Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2013). As such—from a formal perspective—Mangue-Bangue also constitutes the missing link between the tradition of a radically political “outlaw” cinema in Brazil and the bodily and experiential-based spatial interventions stemming from the Neo-Concrete art movement that would lead into Cosmococa’s environments and constitute the spaces for what Oiticica has described as “creleisure” (crelazer), a collective spirit of invention based on the creative performance of desublimated leisure.

A few takes of unlabeled Super 8 footage that D’Almeida and Oiticica recorded in New York in March 1973 document Cosmococa’s affinity to Mangue-Bangue. The silent, seemingly arbitrary and lengthy filming of “non-situations,” of hanging out and doing drugs, is not only reminiscent of Mangue-Bangue, it was also filmed just days after Mangue-Bangue was first screened. At the same time, the fragmentary footage of a repetitive action foreshadows Cosmococa’s iconic 35mm slides, for example: the scattering of cocaine powder across the covers of the Weasels Ripped My Flesh (1970), an LP by The Mothers of Invention, and the New York Times Magazine from March 11, 1973, which features a photograph of Luis Buñuel drawing a line through his eye with a razor blade, recalling the infamous scene from his film Un Chien Andalou (1929); then the rearrangement of the drug as a graphic element on these surfaces, or its reflection in a pocket mirror; and the erasure of the designs made with the powder by “cutting” or blurring or snorting the lines, and repeated rounds of new arrangements and further rearrangements. This footage, evidence of life itself—as are Mangue-Bangue and Cosmococa—is at the same time evidence against itself.19It is perhaps needless to mention that under military dictatorship, the footage not only represents juridical evidence against the artists, but also against the members of the audience, who have gathered to see an illicit movie or artwork.

Even though Mangue-Bangue (filmed in 1970 in Rio, finished in 1971 in London, first screened in 1973 in New York City) disappeared for several decades, it never ceased to exist. It could be argued that the history of Mangue-Bangue’s absence is at the same time the history of its survival, of its presence as discourse, inspiration, formal-aesthetic approach, and bold gesture (queer explicit drug-ridden rock ’n’ roll) that transmuted into the Cosmococas—and as such, set the cornerstone for both the history of cinema expanding into multimedia installations and twentieth-century Latin-American art in general.20Even if the importance of the Cosmococas today is undeniable, this has not always been the case. In 2003, the same year that four of the Cosmococa installations were shown together for the first time, in the city of São Paulo, D’Almeida wondered: “What’s this? Thirty years of waiting! It’s taken so long, incredible as it may seem. . . . The world had to evolve for this work to appear.” See Beatriz Scigliano Carneiro, “Cosmococa—Program in Progress: Heterotopia of War,” in Fios Soltos: A Arte de Hélio Oiticica, ed. Paula Braga, Portuguese/English ed. (São Paulo: Editora Perspectiva, 2008), 220. As D’Almeida rightly observes, the Cosmococas also remained unseen for several decades. It took until 1992 for one of them to be installed in an art space, and until 2005 for the first-ever exhibition of the five Cosmococas as a complete series of installations in Rio de Janeiro, the city where Hélio Oiticica died in 1980 at the age of 43 from the consequences of a sudden stroke, and where D’Almeida continues to live and work.

The presence of Mangue-Bangue, now accessible thanks to Fred Coelho’s and MoMA’s efforts to restore and properly archive it (and even to return a copy of the restored film to D’Almeida), presents us with the challenge of how to pay tribute to a work that refuses to be a “consolidated work of cinema,” does not obey the logic of self-sufficiency, and—according to Oiticica—aims at a “horizontal” principle, as opposed to the “edification” of the heroic avant-garde art work.

In the catalogue accompanying Oiticica’s first international retrospective in 1992, Waly Salomão, a mutual friend of D’Almeida and Oiticica, and a frequent visitor to Mangue—in fact he was the person who brought Neville and Hélio there in the first place—opens his essay with a quote by French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty: “Toute commémoration est aussi trahison” (Every commemoration is also treason). Treason—to use Salomão’s words—would be to try to make Mangue-Bangue into something it is not, or something it never wanted to be. Beginning to recognize that the history of Mangue-Bangue’s presence, and its importance for the present, paradoxically lies outside of itself, in the history of its absence, is an important step toward facing the contradictions at stake. Perhaps embracing one’s own contradictions of wanting to understand it, on the one hand, and to pay tribute to it, on the other, would be the best way to pay homage to a work of art that, first and foremost, is out there to provide evidence against itself.

- 1que eu nunca vi no cinema.” Translation by author. Neville D’Almeida, interview with author, Berlinale 2013, 63rd Berlin International Film Festival, February 8, 2013. Within the context of the Berlinale, I co-curated a Forum Expanded section focused on the Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica. As part of this program, I organized a panel discussion with D’Almeida, a screening of some of Oiticica’s Super 8 films, and exhibitions of Oiticica’s Block-Experiments in Cosmococa—Program in Progress: CC4 Nocagions at Liquidrom (in collaboration with D’Almeida) and CC6 Coke Head’s Soup (in collaboration with Thomas Valentin). Mangue-Bangue was presented on the occasion of the exhibition Cosmococa at Berlin’s Dickinson Gallery in February 2013. I recorded several conversations with D’Almeida in Berlin in early 2013, and on Ilha da Gigóia in Rio de Janeiro in February and March. I have titled these recordings “The Neville Tapes,” and they await thorough editing and publication. Neville D’Almeida and Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz, “The Neville Tapes,” Berlin and Rio de Janeiro, 2013, personal archive of author.

- 2Similar to many other South American countries during the post–World War II period and after the Cuban Revolution of 1959, Brazil suffered a US-backed coup d’etat. In 1964, the Brazilian military staged a coup against the leftist president João Goulart, who was forced to resign and go into exile. The military dictatorship lasted more than 20 years, until 1985. The years between 1968 and 1972 were marked by the violent enforcement of AI-5, which stripped citizens of their basic civil rights and led to severe persecution and execution of members of the political opposition. At that time, many important figures in Brazil’s countercultural movement, including Hélio Oiticica, Gilberto Gil, Caetano Veloso, Jorge Mautner, Helena Ignez, Rogério Sganzerla, and Neville D’Almeida, fled to London, New York, and other cities.

- 3Villaça would later reappear in A Dama do Lotaçao (Lady on the Bus, 1978) and Rio Babilônia (1982), two of D’Almeida’s most successful films.

- 4D’Almeida and Cruz, “The Neville Tapes.”

- 5Neville D’Almeida, Além Cinema (Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Cultural Oi Futuro, 2011), published on the occasion of D’Almeida’s 2011 solo exhibition at Oi Futuro Flamengo, besides containing a full filmography with accompanying texts and interviews, includes a fascinating collection of legal documents tracing the history of censorship in the director’s career.

- 6A Dama do Lotaçao (Lady on the Bus, 1978), based on a play by Nelson Rodriguez, had approximately 6.5 million viewers nationwide, a national box-office record that was only topped more than 30 years later, in 2010, by José Padilha’s Tropa de Elite 2.

- 7Shortly after he finished shooting the film, in 1970, D’Almeida fled Brazil with the original footage and went to London, where he edited the film without sound. A soundtrack was posthumously produced.

- 8In Rio de Janeiro, amid the heart of the urban landscape, one encounters parts of the jungle—branches that have crept in, little tropical islands with waterfalls, toucans, monkeys, and opossums.

- 9D’Almeida and Cruz, “The Neville Tapes.”

- 10See Hélio Oiticica, “Mangue-Bangue,” in Além Cinema, by D’Almeida, 111–12.

- 11See Oiticica “Mangue Bangue.” Capitalization follows original.

- 12Ibid.

- 13See Hélio Oiticica, “Block-Experiments in Cosmococa—Program in Progress,” in Hélio Oiticica: Quasi-Cinemas, ed. Carlos Basualdo, exh. cat. (Cologne, Germany: Kölnisher Kunstverein; New York: New Museum of Contemporary Art; Columbus, Ohio: Wexner Center for the Arts; Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany, in association with Hatje Cantz, 2002), 98–101. Capitalization follows original.

- 14Ibid., 97

- 15See Oiticica “Mangue Bangue,” 111. Capitalization follows original.

- 16On the discovery of Mangue-Bangue in English, see Frederico Oliveira Coelho, “The Rediscovery of Mangue-Bangue,” in Além Cinema, by D’Almeida, 108–10; in Portuguese, see http://objetosimobjetonao.blogspot.com/2009/07/mangue-bangue.html. For Coelho’s outstanding research on Hélio Oiticica’s New York period, see F. Coelho, Livro ou livro-me: os escritos babilônicos de Hélio Oiticica (1971–1978) (Rio de Janeiro: EDUERJ, 2010).

- 17“Quasi-cinemas” was the term coined by Oiticica to refer to a series of cinematic environments or installations that, made during his stay in New York City, combined film and slide projections with music and hammocks in order to immerse the viewer in multisensory experiences. For more information on the notion of “quasi-cinema,” see Basualdo, Hélio Oiticica: Quasi-Cinemas.

- 18For more on the Cosmococas, see Sabeth Buchmann and Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz, Hélio Oiticica and Neville D’Almeida: Block-Experiments in Cosmococa—Program in Progress (London: Afterall; Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2013).

- 19It is perhaps needless to mention that under military dictatorship, the footage not only represents juridical evidence against the artists, but also against the members of the audience, who have gathered to see an illicit movie or artwork.

- 20Even if the importance of the Cosmococas today is undeniable, this has not always been the case. In 2003, the same year that four of the Cosmococa installations were shown together for the first time, in the city of São Paulo, D’Almeida wondered: “What’s this? Thirty years of waiting! It’s taken so long, incredible as it may seem. . . . The world had to evolve for this work to appear.” See Beatriz Scigliano Carneiro, “Cosmococa—Program in Progress: Heterotopia of War,” in Fios Soltos: A Arte de Hélio Oiticica, ed. Paula Braga, Portuguese/English ed. (São Paulo: Editora Perspectiva, 2008), 220. As D’Almeida rightly observes, the Cosmococas also remained unseen for several decades. It took until 1992 for one of them to be installed in an art space, and until 2005 for the first-ever exhibition of the five Cosmococas as a complete series of installations in Rio de Janeiro, the city where Hélio Oiticica died in 1980 at the age of 43 from the consequences of a sudden stroke, and where D’Almeida continues to live and work.