Paz Errázuriz’s photographic oeuvre coincided with that of a group of artists working in the late 1970s and ’80s in Chile who dedicated themselves to an “aesthetic of the margins”. Drawing on works from the Adam’s Apple series, Macarena Gómez-Barris discusses how in Errázuriz’s photographic archive we find the social trace of sex and gender dissidence within the broader context of authoritarianism and patriarchal repression. Such archival traces, the author argues, do not resolve into one meaning but rather show how gender and sexed forms of social life can never be fully contained by state punishment or the logics of art commercialization.

We live in a time when authoritarianism appears as a shadowy figure on the global horizon. The gender and sex freedoms that recently seemed unimpeachable have once again been challenged by an alarming return to nationalisms as witnessed in Brazil, the Philippines, India, the United States, and Britain, as well as by the rise of the Right around the world. With the renewed persistence of monoculture and intolerance comes new forms of state and extra-state violence, such as those inflicted upon people of color and immigrants, as well as new forms of violence targeting queer and trans people living in precarious conditions. Despite gains across the planet, trans, queer, and gender nonconforming bodies continue to be attacked by normative projects of family and nation, as has become apparent in recent regressive anti-gender rhetorical moves and policy debates. Given this political context, what does a view from the Global South tell us about authoritarian sex and gender regimes? What past artistic practices offer new insights into our own era? In our current moment of new attacks and unfreedoms, what does a focus on the social trace of sexual dissidence reveal?1The “social trace” refers to those subjects, processes, and events that cannot be measured through quantitative or qualitative methodologies and that escape the normative disciplinary and disciplining vision of the social sciences and the violence of authoritarianism. Thus, those who live as the targets of state violence must be rendered and considered through other approaches, including decolonial methodologies. For more on this topic, see Herman Gray and Macarena Gómez-Barris, eds., introduction to Toward a Sociology of the Trace (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010). See also Avery Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997).

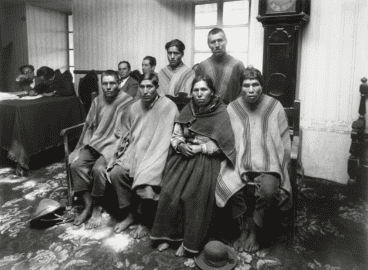

The wave of dictatorships that took power in the Americas in the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s targeted feminists, Indigenous and Afro-descended peoples, and queer and trans communities for not conforming to the racial, gender, and heterosexual norms of the region. As is well documented about Chile, during Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorial reign (1973–90), hundreds of thousands of people were murdered, tortured, and forcibly exiled, producing the category of los desaparecidos (the disappeared), which was salient throughout the hemisphere. Part of the focus of feminist scholarship and art curation about this period has been on the mothers of the disappeared and their important critical human rights and art practices, such as the arpillera weavings that express narratives of loss, trauma, and suffering.2Of the many works that could be cited here, see especially Marjorie Agosín and Cola Franzen, Scraps of Life: Chilean Arpilleras: Chilean Women and the Pinochet Dictatorship (New Jersey: Red Sea Press, 1987). For a longer history of Andean weaving and its importance beyond the colonial matrix, see the work of multimedia artist Cecilia Vicuña, especially in Cecilia Vicuña: Disappeared Quipu, an exhibition organized by the Brooklyn Museum and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 2018. For work on cultural memory in relation to authoritarianism, see also Macarena Gómez-Barris, Where Memory Dwells: Culture and State Violence in Chile (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009); and Vikki Bell, The Art of Post-Dictatorship: Ethics and Aesthetics in Transitional Argentina (New York: Routledge, 2014). Much less has been written in the art world in relation to other social disappearances, including those of queer and trans activists, artists, and sex workers, as in those living at the edges of urban life and at the margins of normative social institutions.3I am mindful that centers and peripheries have long been disturbed, as per Anna Tsing, In the Realm of the Diamond Queen: Marginality in an Out-of-the Way Place (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), and the work of a host of other scholars. However, “lo marginal,” in the context of dictatorship in the Americas, names those who worked within the artistic and political undercurrents inside and outside the normative time/space coordinates of the dictatorship nation. Later in this essay, I describe those who inhabit the material and symbolic location within authoritarian regimes as residing in edge spaces and geographies. By turning to the work of photographer Paz Errázuriz, we are made aware of the rich texture of Global South queer and trans social life that finds sources of freedom beneath the repressive structures of authoritarianism.4There is an important and growing body of work on trans studies in the Americas in English, Spanish, and Portuguese that is too extensive to cite here. See, for instance, Cole Rizki et al., Trans Studies en las Américas, an issue of TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly 6, no. 2 (May 2019). For an introduction to trans studies within a US frame, see J. Jack Halberstam, Trans*: A Short and Quirky Account of Gender Variability(Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018). In the artist’s photographic archive, we find the social trace of sex and gender dissidence, relational joy, and a critical imagination.5For work on the photographic archive and the social otherwise, see Saidiya Hartman’s discussions of photographic documents of Black girls lives in Hartman, Wayward Lives: Beautiful Experiments; Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval(New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2019). On queer diasporic archives and new methods, see Gayatri Gopinath, Unruly Visions: The Aesthetic Practices of Queer Diaspora (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019). Such archival traces disrupt the unilinear repressive structure of the authoritarian gaze and how it obscures cuir (queer) and trans communal imaginaries.

Beneath the Eye of Surveillance

Backed by the US government, Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship represented a backlash to the freedoms of the short period of sex and gender liberation that had preceded it. As women began to experiment with new forms of liberation, and as gay, queer, and trans people experienced openings in the suffocating gender and sex codes inherited from the Spanish colonial era, Christian moral rhetoric was mobilized as a discursive weapon with which to contain the loosening of the tripartite of sex, gender, and nation.6In the 20th and 21st centuries, criminalizing gender and sex difference has often been an authoritarian pathway to the violent biopolitical control of the populace. This is evident in Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro’s recent “anti-gender ideology” speech acts, which make visible how authoritarian rhetoric depends upon normative conventions regarding gender and sexuality.

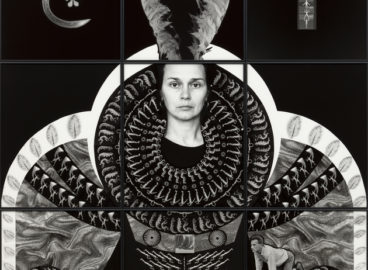

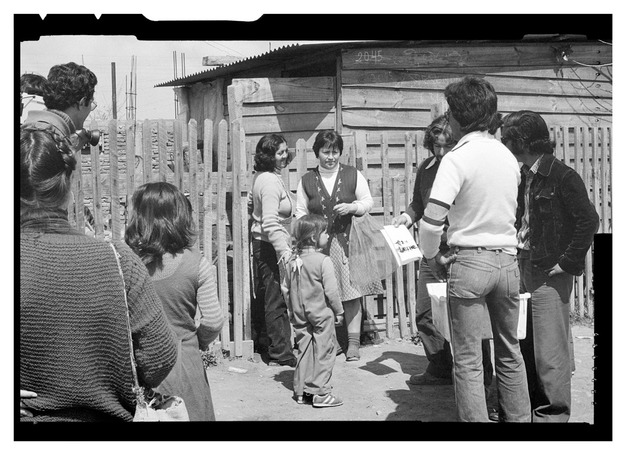

Paz Errázuriz’s important work coincided with that of a group of artists working in the late 1970s and ’80s who dedicated themselves to una estética de los márgenes(an aesthetic of the margins).7See Nelly Richard, La estratificación de los márgenes: Sobre arte, cultura y política (Santiago: Zegers, 1989). Many artists, performers, writers, and poets were a part of this aesthetic movement, including the CADA collective initially comprised of Diamela Eltit, Raúl Zurita, Lotty Rosenfeld, and Juan Castillo, as well as Carmen Berenguer, Pedro Lemebel, Francisco Casas, and Carlos Leppe, among others who worked to develop a multidisciplinary dissident art praxis. Against Pinochet’s censorship practices and the disarticulation of politically left social and artistic movements, the escena de avanzada (avant-guard scene) proposed a radical rupture with the normalization of a coordinated and legislated attack upon nonbinary gendered bodies, Indigeneity, and the working class. Through performance, photography, poetry, radio, and chronicles, the escena de avanzadaintervened in a public sphere that was controlled by Pinochet’s curfews, his shooting cannons, the threat of imprisonment and disappearance, and the general national security doctrine of the dictatorship state.

Metaphorically then, una estética de los márgenes marked the street as a place of plurality, bringing forward an imaginary of the political and artistic undercurrents, or those spaces that functioned beneath the otherwise total control of the state security apparatus. Such art offers creative documentation of the radical potential of nonnormative embodiment. For instance, by taking images within the space of prostíbulos (brothels) in Talca and Santiago, Errázuriz’s camera captured trans performance, intimate desires and connections, alternative femininities, and sexualities within the broader frame of brute patriarchal repression and social prejudice.

Making art under Pinochet’s dictatorship was nearly impossible. Such artistic intention required a political sensitivity and commitment to the importance of transnational solidarity. The escena de avanzada, of which Errázuriz was a part, shared a vision of textured urgency: “During dictatorship times, we did many things. For example, we exhibited at the CEPAL [United Nations Economic Commission on Latin America and the Caribbean] space, and they censored me. I arrived and my photographs were not there, and many of my works were lost. They were never returned by the agencies. We were idealists, and we went where they invited us to exhibit: Italy, Spain, Germany, Croatia; our collective [CADA] travelled around the world to different galleries, to the most eccentric locations, because we searched for diffusion.”8The original text read: “En tiempos de dictadura hicimos muchas cosas, pero por ejemplo en la Cepal, expusimos y me censuraron, llegué y no estaban mis fotos, hay muchos trabajos que se perdieron, no los devolvieron nunca las agencias, eran idealismos de nosotras, íbamos donde nos invitaban a exponer: en Italia, España, Alemania, Croacia, las colectivas viajaban por todo el mundo en distintas galerías, hasta las partes más estrafalarias, porque buscábamos difusión.” See “Entrevista a la fotógrafa Paz Errázuriz: ‘Soy feminista pero no mlitante,’” (Interview with the photographer Paz Errázuriz: ‘I am a feminist, but not militant,’” elciudadano.com, https://www.elciudadano.com/general/entrevista-a-la-fotografa-paz-errazuriz-soy-feminista-pero-no-militante/10/27/. Translation mine. The ideas of diffusion and circulation expressed in this quote were not motivated by a need for capitalist visibility or accumulation, but instead by a critical practice that worked to disrupt the presumed normalcy of emergent neoliberalism, the hegemony of global liberal democracy, and the idea that art and politics have unitary or fixed meanings. For the escena de avanzada, art and politics were not distinct categories, but rather completely fused in their denunciation of dictatorship. In practice, these artists also created transnational linkages through a heterogeneous praxis that responded to urgent times.

In this context, the archive of Errázuriz’s photographs documents the ruptures and difference that cuir and trans bodies make to the brutality of authoritarianism and its aftermath. How does pleasure, imagination, and a future archive of sex dissidence reveal itself in Errázuriz’s photographs? The social traces that show up in such photographic archives do not resolve into one meaning. They instead show how gender and sexed forms of social life can never be fully contained by state punishment or the logics of art commercialization.

Archives from the Sexual Underground

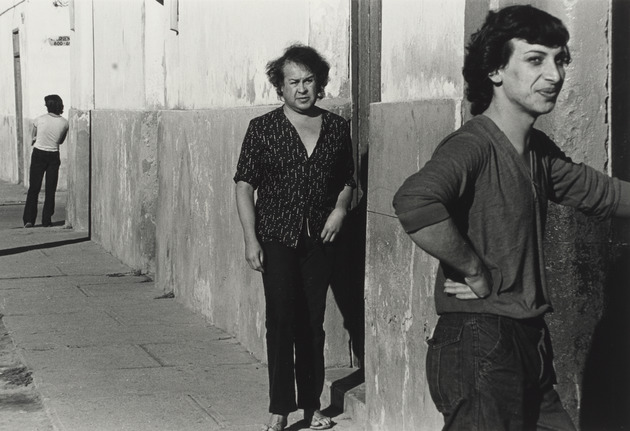

From 1982 to 1987, Errázuriz documented the lives of trans female sex workers in the prostíbulos of La Jaula and La Palmera, in the town of Talca, and within the peripheries of Santiago. Rather than offering ethnographic spectacle, the photographs reveal Errázuriz’s deep investment in a community that was in full view of the state apparatus that attempted to eradicate gender and sexual difference but that was also hidden from it. In the series La Manzana de Adán (Adam’s Apple) from that period, Errázuriz worked closely with journalist Claudia Donoso to produce images that reinscribe the personhoods, libidos, and ways of organizing life out from under its erasure by Pinochet’s narrow implementation of the heteronormative nation.9Because of the threat of censorship and state violence, Errázuriz’s images could not be published until the dictatorship had ended. These photographs were first exhibited in 1989, and the first edition of the book was published in 1990. A second extended version was published in 2014. For more information, see Claudia Donoso and Paz Errázuriz, La manzana de Adán (Adam’s Apple), 1st ed. (Santiago: Zona Editorial, 1990); and Donoso and Errázuriz, La manzana de Adán, exp. ed. (Santiago de Chile: Fundación AMA, 2014). The title of the series, La Manzana de Adán, of course, refers to the telltale sign of biological maleness beneath the meticulously constructed and maintained performance of femininity. In this regard, the title could be seen as an essential reference to the sex of the body assigned at birth. Yet, given the context of the violence of state regimes, we can instead read the title generously, and as noted by Errázuriz, consider the title to refer to the binary gender essentialism that was enforced by authoritarianism.

In the black-and-white photo Evelyn and Hector (1987), which is part of this series, Errázuriz documents two figures who coquettishly face the camera, lovers whose tenderness for each other and for Errázuriz radiates in their expressions. In the affective spillover of the visible bond between the subjects and their photographer, a secondary yet invisible register is also present, one that queers the punctum.10Here, I refer to the need to see photographic archives outside of a purely Western frame of subjectivity. For instance, to use Roland Barthes’s idea of the “punctum,” or the object within the image that jumps out at the viewer, would detract from the relational exchanges of glances and meanings embedded within Errázuriz’s photography. Especially in queer and nonnormative forms of sociality and racialization, no single frame of analysis can address the multiplicity of available relations. For more on decolonial queer visualities in relation to photographic archives, see Macarena Gómez-Barris, “The Plush View: Makeshift Sexualities and Laura Aguilar’s Forbidden Archives,” in Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A., eds. C. Ondine Chavoya and David Evans Frantz, exh. cat. (London: Prestel Publishing, 2018). Evelyn is the sister of Pilar, also documented by Errázuriz’s camera in the series. As Donoso points out, Evelyn and Pilar were close with their mother, Mercedes, who also formed a close bond with Errázuriz.11For a detailed account from Claudia Donoso of the kin relationship, see https://www.scribd.com/document/247201528/Paz-Errazuriz-La-Manzana-de-Adan. The proximity of the closely cropped view into this world is only possible through forms of love, community, and intimacy that exceed the normative parameters of the biological family structure. The photograph’s affect expresses deep care, and the sheer joy that two people feel in each other’s company. It also reveals the pleasure of being documented by Errázuriz’s camera, which via the image, becomes a tool of intimacy rather than a colonial weapon of objectification. As Evelyn coyly faces the camera, Hector looks over her shoulder from behind, with a large grin on their face, hardly hiding the shy delight that is nestled within the intimate bonds of queer relation.

Few if any other photographers at the time registered the domestic queer and trans intimacies hovering below the gaze of surveillance. For instance, in La Palmera(The Palm Tree; 1982–90) and Evelyn (1981), preparation for the nightly work of the alternative sex economy becomes visible only through modes of relation that rely upon Errázuriz’s artistic embeddedness within extended trans communities. In both photographs, the doubling of the mirror, a quintessential trope of trans visuality, and the view into Chilean domestic interiors provide the grounded aesthetics of trans social life that the film Una Mujer Fantástica (A Fantastic Woman; 2017), directed by Sebastián Lelio, later depends upon. Though it is hard to substantiate how much Errázuriz’s images influenced the aesthetics of Una Mujer Fantástica, it is only through this later film that we see the full force of an intimate view of southern trans subcultures and their mediation. Unlike members of the community that Errázuriz documents, however, Marina, the transgender protagonist of Una Mujer Fantástica, is chronicled as alone, alienated, and barely enduring the violent aftermath of nonrecognition. Indeed, Errázuriz’s archive challenges the presumption of the individuation and isolation of trans subjectivity under surveillance.

As a mediator of social worlds and political imaginaries, Errázuriz uses the camera in the ways I have elsewhere called a decolonial cuir femme methodology.12For a fuller discussion of this methodology, see Macarena Gómez-Barris, The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives(Durham: Duke University Press 2017). Rather than extracting knowledge from the field through a disciplinary framing, this multivalent method seeks to open up a space for experiential porousness, letting the immediacy and intimacies of the surround seep in. This is not an objective related to profit, but rather a political objective that is motivated by producing critical solidarity with those under constant threat of surveillance, gentrification, extraction, absorption, and erasure.13This concept is one that I originally developed in relation to majority Indigenous territories in the southern hemisphere, where extractive industries have left their violent imprint. The methodology is incomplete without a fuller discussion of decolonizing land and territory, as critical Indigenous Studies have importantly shown. For a concise discussion of this idea, see Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1, no. 1 (2012), https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/18630. See also Jodi Byrd, Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critique of Colonialism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011). Connection to social movements and praxis is also key to this. The work of critical and ethical solidarities in relation to those under duress of state violence, through feminist of color practices of engagement, listening, political imagination, and action, is something that a decolonial cuir femme praxis offers. Such relational work is enlivened by the social life-force of edge geographies and their vitality. Within the Chilean context, Nelly Richard and others have referred to the space of gender and sex alternatives as lo marginal (of the margins) to describe the cultural formations of those who reside below and beyond normative social and political life. Richard has shown how gender and sex ideologies in the Global South operate through codes long inscribed by the patriarchal nation, and whose emancipation can only take place through the activities of feminist, queer, and trans disruption.14See Nelly Richard, Cultural Residues: Chile in Transition, trans. Theodore Quester and Alan West-Durán (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004). Thus, she turns to the marginal spaces of symbolic and material multiplicity as the sites of her analysis and possibility.

Indeed, Paz Errázuriz documents queer and trans lives within the peripheries of capitalist and authoritarian violence. As Errázuriz explains with respects to her own positionality in relation to her subjects: “I guess my point of view has been an anthropological one. I did not comment on their lives; I wanted to be more of an accomplice than a foreigner or an outsider.”15See Philomena Epps, “La Manzana de Adan by Paz Errázuriz,” Elephant, March 11, 2018, https://elephant.art/la-manzana-de-adan-by-paz-errazuriz/. In her use of the term “anthropological,” Errázuriz does not refer to a distancing move, or to the disciplinary lens of observation; instead, she describes her proximity and adjacency to Evelyn and Hector’s life as a form of attachment to the deep bonds of familiarity that she feels as part of queer and trans relationalities.16On queer relationality, see Ann Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003).

Seeing into the Void

If you look at many of Paz Errázuriz’s images, you will notice that behind the figure of the portrait, there is a void, or a negative geography. In the photograph Evelyn(1982), for instance, the direct address of the subject is framed by the negative space behind her, as if the domestic space is about to engulf her. Yet Evelyn is steadily poised, and confident in her gaze, with her hands gently folded in front of her as if to reveal a steady patience with the static temporality of authoritarianism. Evelyn’s trans embodiment seemingly resides in the sliver-edge space between normative interiors and dangerous exteriors, in a refuge-transitive geography. Evelyn also seems to exist in a transtemporal time and place, that is, a time not ruled by authoritarian temporality. Here we might think about an excess beyond what Beth Freeman has generatively termed as “chrononormativity,” or the experience of time within a normative framework.17For a thorough discussion of this important concept and application, see Beth Freeman, Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010). On trans-temporalities, see Kadji Amin, “Temporality,” Transgender Studies Quarterly 1, nos. 1–2 (2014): 219–22. See also, Jack Halberstam, In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives, Sexual Cultures (New York: New York University Press), 2005.

This sliver-edge space of trans communal living, it seems to me, shows up in Errázuriz’s camera in ways that cannot be easily coded as lo marginal—in part, because to focus our attention on marginality is to miss the deeper subversive aesthetics and practices at play in the making of the photograph. In the catalogue accompanying a recent group exhibition at the Barbican, of which Errázuriz’s work was a part, Lucy Davies writes, “Errázuriz has since returned over and again to the lives of those who find themselves on life’s margins . . . to nomad minorities and circus performers, as well as the elderly and those confined to psychiatric wards—groups who seem to lack a voice everywhere, dictatorship or not.”18See Epps, “La Manzana de Adan by Paz Errázuriz.” Yet, rather than merely seeking to give voice to those who live in the marginal spaces of dominant society, Errázuriz’s work represents a critical praxis of documentation, a political gesture toward a queer and trans social photography that makes edge relations visible within the obscurity of authoritarianism. As Errázuriz describes: “For me, it was a form of activism. . . . Photography let me participate in my own way in the resistance waged by those of us who remained in Chile. It was our means of showing that we were there and fighting back.”19Ibid. Rather than document the death worlds produced by the dictatorship, Errázuriz focused on the textures and imaginaries of everyday life as a trans person through the lives of Evelyn and others. Even beyond the model of resistance articulated in this quote, I would argue that Errazúriz’s camera shows how sex and gender dissidence can never be fully eradicated by surveillance capitalism, the authoritarian state, or colonial governmentality. Queer and trans communal social life, in particular, always finds new forms of expression and manifestation, as Errázuriz’s camera reminds us.

Embodying Dissent

In Beyond the Pink Tide: Art and Political Undercurrents, I write about the difference that cuir and trans perspectives make in relation to unpacking the violence of authoritarianism.20Macarena Gómez-Barris, Beyond the Pink Tide: Art and Political Undercurrents (University of California Press, 2018). More broadly, the book shows how art and art praxis, when connected to social movements, offer new ways to think, act, and do politics beyond the nation state. These political undercurrents and their aesthetic practices offer important challenges to normative ideas about dominant society. Errazúriz’s photography also enlivens such undercurrent worlds, offering a living archive of embodied dissent. The photographic archive can be a dangerous place. It can fall prey to the dominant gaze of ethnographic spectacle or be the site for romantic portrayals of gender and sex difference. Outside of these poles, how can we think about photography that documents sex dissidence as a challenge to nationalism and dictatorship? Can it be a site of refusal and of imagining social and political life otherwise?

Working within the alternative sex economies outside of Santiago, in the shadow spaces of street corners, and within domestic interiors in working-class neighborhoods, Errázuriz created an important archive of sex dissidence. This series of images of trans lives both warns us about this new dangerous moment in the rise of authoritarianism, and teaches us how to see within it by documenting worlds of pleasure, imagination, fantasy, solidarity, and intimacy from inside the storm’s eye of state terror.

I would like to thank Jay Levenson and the group of talented curators and museum staff that I have met at MoMA through projects and seminars affiliated with C-MAP and the Cisneros Institute. I especially want to thank Iberia Pérez for her editorial insights, and River Bullock for taking time to talk with me about Paz Errázuriz’s small, but powerful photographic archive at MoMA. I am also grateful to Sarah Meister and other curators involved in the acquisition of Errázuriz’s work for their important commitment to collecting dissident art.

- 1The “social trace” refers to those subjects, processes, and events that cannot be measured through quantitative or qualitative methodologies and that escape the normative disciplinary and disciplining vision of the social sciences and the violence of authoritarianism. Thus, those who live as the targets of state violence must be rendered and considered through other approaches, including decolonial methodologies. For more on this topic, see Herman Gray and Macarena Gómez-Barris, eds., introduction to Toward a Sociology of the Trace (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010). See also Avery Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997).

- 2Of the many works that could be cited here, see especially Marjorie Agosín and Cola Franzen, Scraps of Life: Chilean Arpilleras: Chilean Women and the Pinochet Dictatorship (New Jersey: Red Sea Press, 1987). For a longer history of Andean weaving and its importance beyond the colonial matrix, see the work of multimedia artist Cecilia Vicuña, especially in Cecilia Vicuña: Disappeared Quipu, an exhibition organized by the Brooklyn Museum and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 2018. For work on cultural memory in relation to authoritarianism, see also Macarena Gómez-Barris, Where Memory Dwells: Culture and State Violence in Chile (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009); and Vikki Bell, The Art of Post-Dictatorship: Ethics and Aesthetics in Transitional Argentina (New York: Routledge, 2014).

- 3I am mindful that centers and peripheries have long been disturbed, as per Anna Tsing, In the Realm of the Diamond Queen: Marginality in an Out-of-the Way Place (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), and the work of a host of other scholars. However, “lo marginal,” in the context of dictatorship in the Americas, names those who worked within the artistic and political undercurrents inside and outside the normative time/space coordinates of the dictatorship nation. Later in this essay, I describe those who inhabit the material and symbolic location within authoritarian regimes as residing in edge spaces and geographies.

- 4There is an important and growing body of work on trans studies in the Americas in English, Spanish, and Portuguese that is too extensive to cite here. See, for instance, Cole Rizki et al., Trans Studies en las Américas, an issue of TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly 6, no. 2 (May 2019). For an introduction to trans studies within a US frame, see J. Jack Halberstam, Trans*: A Short and Quirky Account of Gender Variability(Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018).

- 5For work on the photographic archive and the social otherwise, see Saidiya Hartman’s discussions of photographic documents of Black girls lives in Hartman, Wayward Lives: Beautiful Experiments; Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval(New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2019). On queer diasporic archives and new methods, see Gayatri Gopinath, Unruly Visions: The Aesthetic Practices of Queer Diaspora (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019).

- 6In the 20th and 21st centuries, criminalizing gender and sex difference has often been an authoritarian pathway to the violent biopolitical control of the populace. This is evident in Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro’s recent “anti-gender ideology” speech acts, which make visible how authoritarian rhetoric depends upon normative conventions regarding gender and sexuality.

- 7See Nelly Richard, La estratificación de los márgenes: Sobre arte, cultura y política (Santiago: Zegers, 1989).

- 8The original text read: “En tiempos de dictadura hicimos muchas cosas, pero por ejemplo en la Cepal, expusimos y me censuraron, llegué y no estaban mis fotos, hay muchos trabajos que se perdieron, no los devolvieron nunca las agencias, eran idealismos de nosotras, íbamos donde nos invitaban a exponer: en Italia, España, Alemania, Croacia, las colectivas viajaban por todo el mundo en distintas galerías, hasta las partes más estrafalarias, porque buscábamos difusión.” See “Entrevista a la fotógrafa Paz Errázuriz: ‘Soy feminista pero no mlitante,’” (Interview with the photographer Paz Errázuriz: ‘I am a feminist, but not militant,’” elciudadano.com, https://www.elciudadano.com/general/entrevista-a-la-fotografa-paz-errazuriz-soy-feminista-pero-no-militante/10/27/. Translation mine.

- 9Because of the threat of censorship and state violence, Errázuriz’s images could not be published until the dictatorship had ended. These photographs were first exhibited in 1989, and the first edition of the book was published in 1990. A second extended version was published in 2014. For more information, see Claudia Donoso and Paz Errázuriz, La manzana de Adán (Adam’s Apple), 1st ed. (Santiago: Zona Editorial, 1990); and Donoso and Errázuriz, La manzana de Adán, exp. ed. (Santiago de Chile: Fundación AMA, 2014).

- 10Here, I refer to the need to see photographic archives outside of a purely Western frame of subjectivity. For instance, to use Roland Barthes’s idea of the “punctum,” or the object within the image that jumps out at the viewer, would detract from the relational exchanges of glances and meanings embedded within Errázuriz’s photography. Especially in queer and nonnormative forms of sociality and racialization, no single frame of analysis can address the multiplicity of available relations. For more on decolonial queer visualities in relation to photographic archives, see Macarena Gómez-Barris, “The Plush View: Makeshift Sexualities and Laura Aguilar’s Forbidden Archives,” in Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A., eds. C. Ondine Chavoya and David Evans Frantz, exh. cat. (London: Prestel Publishing, 2018).

- 11For a detailed account from Claudia Donoso of the kin relationship, see https://www.scribd.com/document/247201528/Paz-Errazuriz-La-Manzana-de-Adan.

- 12For a fuller discussion of this methodology, see Macarena Gómez-Barris, The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives(Durham: Duke University Press 2017).

- 13This concept is one that I originally developed in relation to majority Indigenous territories in the southern hemisphere, where extractive industries have left their violent imprint. The methodology is incomplete without a fuller discussion of decolonizing land and territory, as critical Indigenous Studies have importantly shown. For a concise discussion of this idea, see Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1, no. 1 (2012), https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/18630. See also Jodi Byrd, Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critique of Colonialism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011). Connection to social movements and praxis is also key to this. The work of critical and ethical solidarities in relation to those under duress of state violence, through feminist of color practices of engagement, listening, political imagination, and action, is something that a decolonial cuir femme praxis offers.

- 14See Nelly Richard, Cultural Residues: Chile in Transition, trans. Theodore Quester and Alan West-Durán (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004).

- 15See Philomena Epps, “La Manzana de Adan by Paz Errázuriz,” Elephant, March 11, 2018, https://elephant.art/la-manzana-de-adan-by-paz-errazuriz/.

- 16On queer relationality, see Ann Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003).

- 17For a thorough discussion of this important concept and application, see Beth Freeman, Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010). On trans-temporalities, see Kadji Amin, “Temporality,” Transgender Studies Quarterly 1, nos. 1–2 (2014): 219–22. See also, Jack Halberstam, In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives, Sexual Cultures (New York: New York University Press), 2005.

- 18See Epps, “La Manzana de Adan by Paz Errázuriz.”

- 19Ibid.

- 20Macarena Gómez-Barris, Beyond the Pink Tide: Art and Political Undercurrents (University of California Press, 2018).