This text is a reimagined transcription of a series of conversations between Prabha Sahasrabudhe and Indira Gandhi that took place in 1960 at the Westbury Hotel in New York City. At the time, Sahasrabudhe was a teaching artist at The Museum of Modern Art and pursuing a PhD in art education at New York University, and Gandhi, the daughter of Jawaharlal Nehru, then prime minister of India, was president of the Indian National Congress. The reason for their meetings was to discuss bringing an adaptation of MoMA’s Children’s Art Carnival to India. Sahasrabudhe’s memories of what he and Gandhi took into consideration when adapting a US pedagogical experiment to the Indian context provided the foundation for this re-created dialogue.

Ephemerality, intangibility, un-collectability, performativity, and temporality are all conditions intrinsic to art education. Once an action in art education is considered over, its participants (educators, learners, artists, policy makers) “take their presence away with them, embodied in personal memories and narrations of the events.”1Carmen Moersch, “Application: Proposal for a Youth Project Dealing with Forms of Youth Visibility in Galleries,” in Magic Moments: Collaboration between Artists and Young People, ed. Anna Harding (London: Black Dog, 2005), 198. Oral histories are key tools to capture experiences of learning. They are, in many cases, the last strand from which to pull a pale representation of how something was. The way in which the interviewee narrates the events prompted by the particular take of the interviewer creates a story that belongs neither to the past nor to the present. It lives in a third space configured by emotional memory and the benefit of hindsight. Despite the inherent subjectivity and complexity of oral histories, they still remain priceless pieces to scaffold the history of art education. On December 2018, in the role of interviewer, I was privileged to get one such narration.

Dr. Prabha Sahasrabudhe, a retired professor of art and art education at Teachers College, Columbia University, in New York City, welcomed me into his home in New Jersey. With his characteristic natural flair, he made me coffee as he quietly shared his life story and achievements in art education. As he spoke, he repeatedly referred to the many people he had been blessed to meet and learn from, claiming that he had met so many brilliant minds in the field because he purposefully sought out those he thought would nourish him as an educator.

There was one name that came up over and over again: Indira Gandhi.

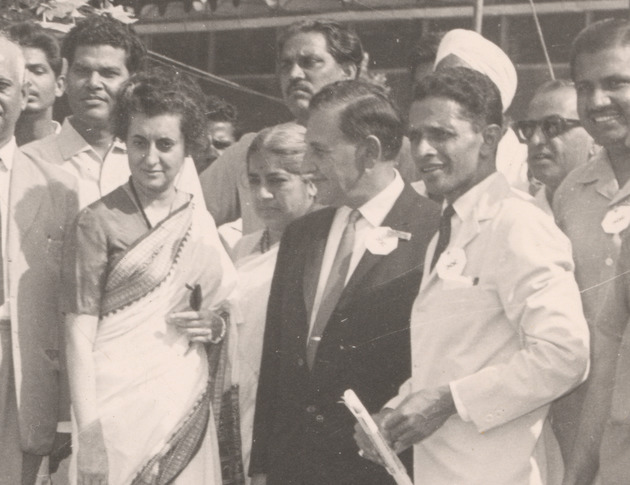

Sahasrabudhe first met Gandhi on November 9, 1960, at the Westbury Hotel. “Indira Gandhi,” he said, “was going to be in the city for three days. So, she and I spent three days of breakfast time . . . in a long breakfast, talking about what she wanted to do.”2Prabha Sahasrabudhe, interview by author, Pompton Lakes, New Jersey, 2019.

Indira Gandhi would go on to become India’s first female prime minister, a position she held from 1966 to 1977 and again from 1980 to 1984. Her political career was surrounded by controversy, and her life cut short when she was assassinated by her own bodyguards in 1984. Obviously, none of this had taken place when she met with Sahasrabudhe for breakfast in 1960, but she was nonetheless already a very public figure at the time and her political aspirations were gaining momentum.

While Indira Gandhi remains a compelling figure in the history of India, I confess that I was surprised to hear her name mentioned in connection to the field of art education. When I asked Dr. Sahasrabudhe what led to the opportunity to share three breakfasts with her, he replied, “It was the idea of bringing the Children’s Art Carnival to India.”3Ibid.

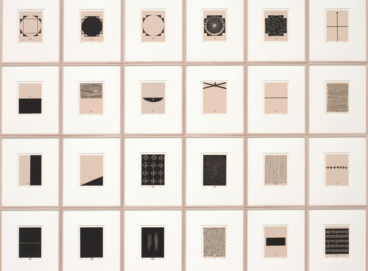

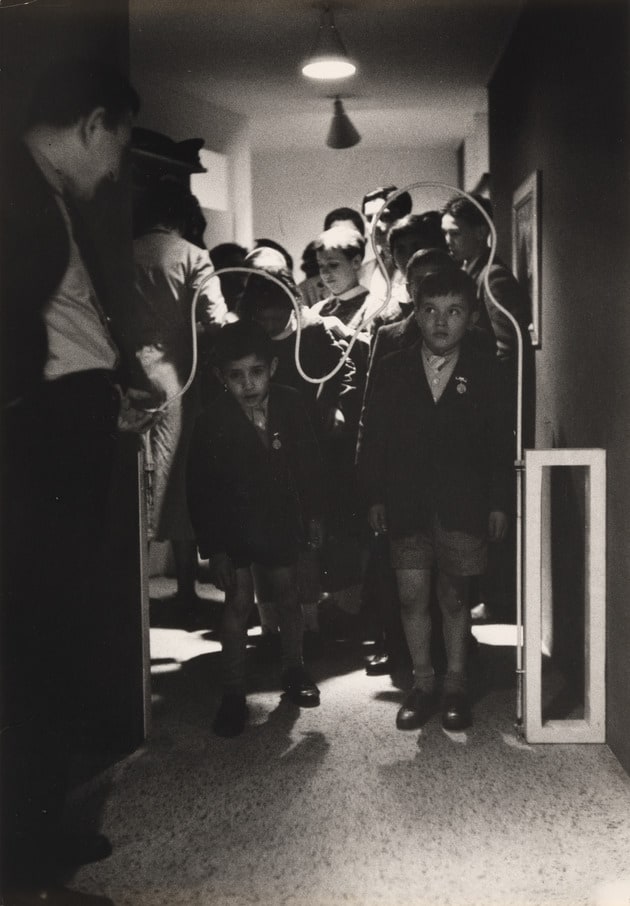

The Children’s Art Carnival was a pedagogical experiment that originated at The Museum of Modern Art in 1942. Conceived by Victor D’Amico, then director of education at MoMA, the Carnival was designed to cultivate the development of children’s imaginations and creativity. Upon entering through a child-shaped contour gate, young visitors would find themselves in a semi-darkened room painted in deep blues and greens. Spotlights revealed works of art chosen by children or made especially for them by modern artists such as Alexander Calder, Joan Miró, Ruth Vollmer, Toni Hughes, William Zorach, and Chaim Gross. These objects were displayed at a child’s eye level—a height that allowed them to be touched and/or manipulated.

The Carnival plan consisted of two distinct areas, or galleries: one for motivating or inspiring children, and the second for engaging them in art activities. In the inspirational area, children explored the fundamentals of line, space, light, and motion through play with specially designed toys. In the studio workshop, they made their own creations: paintings, collages, mobiles, and other three-dimensional constructions. To foster independent activity and concentration, as well as to prevent adult interference or influence, adult visitors were blocked from entering but could observe from the gate and through specially designed portholes. The only adults present were teaching artists who had been trained to enrich and broaden the children’s experience by motivating and challenging them in unimposing ways. As D’Amico expressed: “The artist has a close kinship with the child in imagination, liveliness of spirit, and creative response. As a result, the truly creative artist is a child’s best teacher.”4Modern Art for Young People [MoMA Exh. #279, February 21–March 11, 1945], Victor D’Amico Papers VI.50. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.

The Carnival was held annually at the Museum between 1942 and 1964 for a period of six to eight weeks and was open to children between the ages of four and twelve.5Over the course of 22 years, there was fluctuation in the age range but 4 to 12 was most common. Carnival sessions lasted one hour.

In 1957, the US Government commissioned duplicate editions of the Carnival for international trade fairs in Milan and Barcelona and, in 1958, for the US Pavilion at the Brussels World’s Fair.6At the Brussels World’s Fair the Children’s Art Carnival was named Children’s Creative Center. It was estimated that in Brussels, over the course of six months, more than 55,000 children from different countries visited the Carnival and that more than 10,000 adults from different parts of the world had observed it in operation.7Final Report: Children’s Creative Center. US Pavilion. Brussels World Fair 1958. Charles Henry Alston Papers, 1924–1980, Box 1, Folder 6. Archives of American Art, Washington DC. Indira Gandhi was among those observers.

Gandhi visited the fair in Brussels with Dorothy Norman, an arts advocate and longtime friend of the Gandhi family. Gandhi was enthusiastic about the Carnival, and so later, she, Norman, and Pupul Jayakar (a cultural activist and writer who had previously worked closely with MoMA) visited D’Amico to discuss the possibility of creating a version of the Carnival for India, which they envisioned might circulate to several cities and then be installed permanently in New Delhi.

Around the same time, Sahasrabudhe had become acquainted with both the Carnival and D’Amico in New York and expressed his interest to D’Amico in the possibility of setting up a similar art center in India. Moreover, he had spent a great deal of time observing the Carnival in operation. If there was to be a Children’s Art Carnival in India, D’Amico felt that Sahasrabudhe was the right person to coordinate it.8“Background Information—The Children’s Art Carnival.” International Council & International Program Records I.B.881. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. Funding for such an undertaking was, however, uncertain.

Almost simultaneously, a different project was in the making: in September 1960, Sahasrabudhe was approached by officials from the Government of India, at the request of Jayakar, to propose a tentative plan for a National Children’s Museum in Delhi.

By 1960, Sahasrabudhe had been asked to coordinate two projects, neither of which had secured funding: the adaptation of MoMA’s Children’s Art Carnival for India and the proposal for a National Children’s Museum in Delhi. This was the situation when D’Amico informed Sahasrabudhe that Indira Gandhi was coming to New York City for a long-dreamed-of private visit and suggested that he should meet with her.

On November 9, 1960, Gandhi and Sahasrabudhe met for the first of the three breakfasts they were scheduled to share. It is not unusual that key moments in decision-making in art education go unnoticed and undocumented as they happen. Sometimes it is only after years, maybe even decades, that one traces great projects back to their moment of inception. Such was the case when Dr. Sahasrabudhe and I, sitting in his house having coffee, decided that going back sixty years to those breakfasts and trying to re-create the dialogues that took place over them would be an unusual but worthwhile experiment. When we started this endeavor, we couldn’t anticipate that in the process of reconstructing history, its ephemerality would become ruthlessly explicit with Dr. Sahasrabudhe’s passing on January 27, 2019. The experiment we started together, I finish alone in this article. I humbly ask the reader to bear with me in this speculative act of rebellion against art education memory loss.

In attempting to reconstruct Sahasrabudhe’s and Gandhi’s dialogue, I have drawn upon my own conversations with Dr. Sahasrabudhe in the months before he died and integrated his narrative and the information he provided about his exchange with Gandhi with direct quotes from the latter’s correspondence and writings. The content of these conversations as presented here has been checked against different accounts in order to represent Dr. Sahasrabudhe’s and Gandhi’s words and positions as accurately as possible.

Questions such as how many hours they spent together or what they were having for breakfast are missing. There are other inevitable gaps that are impossible to fill now that both Gandhi and Dr. Sahasrabudhe are gone. However, the scattered pieces that do remain deserve attention as they sparked key ideas that Gandhi and Sahasrabudhe would continue to develop together in the decades to come. What follows highlights possible aspects of their discussions—those moments in which Gandhi and Sahasrabudhe speculate about what should be considered when adapting a US experiment in art education, that is, the Children’s Art Carnival, to the context of major cities in India.

Sahasrabudhe’s memories of his conversations with Gandhi were that they flowed between the defense of art education as a means of transforming society and the asymmetrical influence of Western creative teaching methods. His narrative not only provides a historical record, it also offers an opportunity to recognize and question the art pedagogies of our own time.

FIRST BREAKFAST: “We need not waste time on preliminaries.”

It was not a particularly cold November morning on New York City’s Upper East Side when Prabha Sahasrabudhe, a thirty-two-year-old art educator entered the luxurious Westbury Hotel in New York City. At the suggestion of his supervisor Victor D’Amico, then director of education at The Museum of Modern Art, Sahasrabudhe was there to meet with Indira Gandhi, president of the Indian National Congress.9Victor D’Amico (1904–1987) was an American teaching artist and the founding director of the Department of Education of The Museum of Modern Art, New York. It was breakfast time, and when Sahasrabudhe entered the elegant dining room of the hotel, Gandhi was already sitting at a table and waiting for him.

INDIRA GANDHI: Pupul [Jayakar] has told me about you, and she would like you to be the director of a new children’s museum and adjoining children’s recreation-cum-education center [Bal Bhavan] in New Delhi.10Pupul Jayakar née Mehta (1915–1997) was an Indian cultural activist and writer, best known for her work on the revival of traditional and village arts, handlooms, and handicrafts in post-independence India. She served as a cultural adviser to Indira Gandhi. At the request of Jayakar, officials from the Government of India approached Sahasrabudhe in September 1960 to request he submit a plan for an “Art Education Center” that the Government was considering sponsoring. I know at present you are connected with New York University and work with [Victor] D’Amico at The Museum of Modern Art, but nevertheless, I have asked the Indian Ministry of Education to send you the relevant papers as well as blueprints of the plans for the museum so that “we need not waste time on preliminaries.”11Indira Gandhi, Indira Gandhi, Letters to an American Friend (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1985), 75.

PRABHA SAHASRABUDHE: Mrs. Jayakar requested that I propose a plan for the children’s museum, which the Government [of India] would like to sponsor.12Sahasrabudhe had been told that the museum was confirmed, but in fact, it wasn’t. When he arrived in Delhi a year later to assume the role of museum director, there was no building or museum to direct.

IG: My father [Jawaharlal Nehru] loves museums and never misses an opportunity to visit them, however busy his schedule.13Jawaharlal Nehru (1889–1964) was the first prime minister of India and a central figure in Indian politics before and after independence. With his knowledgeable interest and appreciation, he is a curator’s delight. He would like our country to be dotted with children’s museums, because he believes that even a small beginning is better than none at all—and that we should not let our lack of resources deter us from forming collections even though they might at first be inadequately housed and displayed. A few years ago, my father visited the Artek Pioneer Camp in the USSR, and he was moved to see hundreds of children immersed in the world of fantasy and creativity, unlimited by barriers of caste, class, religion, or place.14Artek, a youth camp on the Black Sea, was one of the most prominent examples of how Soviet pedagogues and architects collaborated to create educational institutions for children. It aimed at uniting children from all over the Soviet Union to share an outdoor, or “pioneer” experience, within the natural environment. As prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru visited the camp during his first official visit to the USSR in 1955. The idea of developing a similar institution in India, one solely for children, emerged in his mind. Following the “pioneer camp” schema, my father founded Bal Bhavan, which began offering physical education and science activities in a tin shed at Turkman Gate in Delhi. This project marked the start of a nationwide mission to promote the creative enhancement of children through play in a child-friendly environment. We now aim to build the first National Children’s Museum in the New Delhi Bal Bhavan.15Gandhi, foreword to Museums for Children—A Seminar: Why, What and How? (New Delhi: Bal Bhavan and National Children’s Museum New Delhi, 1962), vii.

PS: I’ll present a preliminary proposal for the National Children’s Museum next month. But in light of the transitional period in India’s educational reconstruction program, plans for educational institutions should not contain final blueprints for proposed building construction.16The attainment of independence in India led to changes in the Indian educational setup. The process of addressing the growing demands of education as a consequence of industrialization and modernization was called the “Educational Reconstruction.” The emphasis should be to establish the need for the center and its significance to India’s educational program, rather than to focus on the architecture of its buildings and grounds.

IG: “We should try to use whatever resources and materials are immediately available while constantly endeavoring to improve the personnel, the installation, and the nature and quality of exhibits. The same applies to the building and other exterior aspects.”17Gandhi, foreword to Museums for Children, viii. “I am genuinely concerned about the present educational system in India. I was fortunate to attend institutions and to be taught by people whose teaching went far beyond the normal routine. But my own experience has made me doubtful about the value of most schools.”18Indira Gandhi, Indira Gandhi, Letters to an American Friend (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1985), 138. “After all, plenty of literate people get nowhere, and vice versa. We need of course, to wipe out illiteracy, but people of intelligence can do remarkable things under any circumstances, if given the opportunity.”19Ibid., 14. “I am convinced that if we had been able to change our outmoded educational system when we became free, it would have made a big difference. We are now trying to see what can be done.”20On August 15, 1947, the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed the Indian Independence Act, transferring power to the constituent assemblies. Quote from Gandhi, Indira Gandhi, Letters to an American Friend, 138.

PS: The problems that educational reform in India faces, cannot be thought of in unilinear terms. What applies to urban India may not be suitable for rural India, for example. India has often been described as a land of contrasts. This contrast is nowhere clearer than in terms of education. No doubt some states and metropolitan cities can boast of modern schools or school systems; but India’s villages, which first entered the picture after India achieved independence in 1947, have been grossly neglected for decades. In my opinion, what rural India needs is a program that extends community services—a program that will meet these areas’ deficiencies in goods, services, and amenities. It will be quite some time before art education comes to the Indian villages.21Prabha Sahasrabudhe, “A Conceptual Framework for a Children’s Art Education Center, in New Delhi, India” (PhD dissertation, New York University, 1961), 7.

IG: Pupul says that in the schools in urban India that have more ambitious art departments and programs, there is a false sense of “Indian” or “Oriental,” as opposed to modern or contemporary, which further narrows the child’s sensibility. In the name of the “great and ancient tradition,” direct seeing and listening by the child diminishes, and ideological, conceptual grooves of thinking become established. Tradition becomes synonymous with making copies from Ajanta, or the work of the Bengal School.22The Ajanta Caves are 30 rock-cut Buddhist cave monuments that date from the 2nd century BCE to about 480 CE. They are located near Ajanta village in the Aurangabad district of Maharashtra state in western India. Since 1819, many attempts have been made to document the paintings inside them. From 1872 to 1885, John Griffiths, principal of the Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy School of Art, and seven students spent every winter at the caves, producing approximately 300 copies of the paintings within. Essentially, it leads to imitation. This is so even in schools that profess to be progressive in their approach. Here there is an attempt to reject the so-called traditional, but the intent is still not with discovery and perception in mind. So, the whole approach becomes rooted in imitation, whether it be of works of the past, or of the present.23Pupul Jayakar, “The Place of Children’s Museum in Art Education,” in Museums for Children, 5.

PS: Philosophically, the education of the senses, the importance of learning by doing and thinking with the hands, the joy of creative work, the importance of constructive activity, and other art education premises have become accepted notions. But the reality is that in the schools where art is taught, it is approached as training for skill in drawing based on so-called indoctrinary methods.24The term “indoctrinary” is commonly used in the field of art education to refer to practices that potentially hamper creative activity. Sahasrabudhe’s definition of indoctrinary methods in children’s education include fostering competition, encouraging imitation, and allowing expectations from adults (with the exception of trained teaching artists) to interfere with the individual development of the child. Until recently, education has stressed only the intellectual and practical needs of the individual. Education has been the acquisition of useful and valuable knowledge, skills, and understanding. Existing patterns of social and cultural conditions have defined educational needs. This education, however, has neglected human needs in the aesthetic realm. “The need to experience, and the need to relate to the world, the need for self-discovery through self-expression and the need for self-identification, and other such needs have only recently become part of our own educational thinking.”25Sahasrabudhe, “A Conceptual Framework for a Children’s Art Education Center,” 3. “Reform in education and the rethinking of current practices in education, appraisal of new trends, and newer ideas on education very rarely come down from the top. [. . .] It is the lay people, the teachers and parents who must advocate for change.”26Prabha Sahasrabudhe, “A Blueprint for the National Children’s Museum,” in Museums for Children,” 141.

IG: “We want persons with ideas to stimulate our own people to new thinking.”27Gandhi, Indira Gandhi, Letters to an American Friend, 137. I’ve seen the Children’s Creative Center in Brussels, which Victor D’Amico created for young visitors. It stresses the tactile, sensory, and visual qualities of the materials on view, encouraging the children to paint what they experience, in terms of their own imaginations. I am enthusiastic about D’Amico’s project and think it would be relevant to Indian children. Pupul thinks so too. We have scheduled a visit for today with Dorothy [Norman] and Victor D’Amico at The Museum of Modern Art.28Dorothy Norman (1905–1997) was an American photographer, writer, editor, arts patron. Gandhi met Norman in New York in 1956, and the two developed a friendship that was to continue throughout their lives.

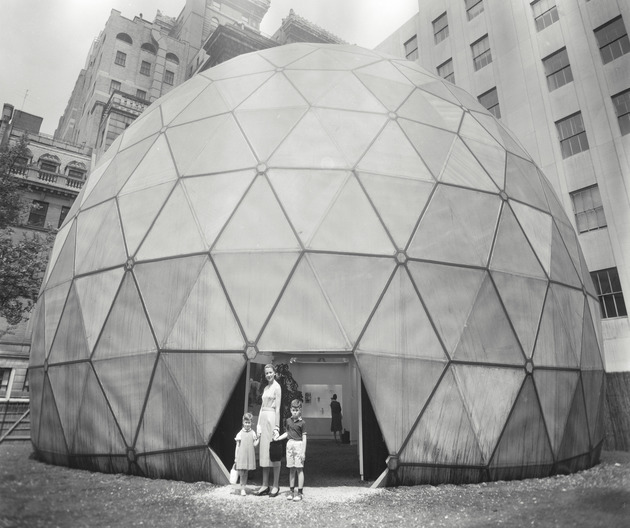

That afternoon, Sahasrabudhe and D’Amico showed Gandhi and Norman the Children’s Art Carnival at MoMA, held that year inside the Buckminster Fuller Dome in the garden of the Museum.

During the visit, D’Amico registered a statement made by Gandhi: “Mr. D’Amico, we want an Art Carnival of our own and we want you to come with a staff of teachers and train our teachers so that we will be able to carry on creative teaching for our children.”29Victor D’Amico, “The Children’s Art Caravan: Creative Education on Wheels,” in Arts and Activities: The Teacher’s Arts and Crafts Guide(1970), Victor D’Amico Papers, IV.C.7, pp. 13–19. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.

After visiting the Children’s Art Carnival at MoMA, Gandhi was convinced about wanting to secure a Children’s Art Carnival for India. An appointment with Sahasrabudhe was made for the following morning so the two could work together not only on a plan to raise interest and funds but also to define the purpose of such a project. They decided that the Carnival in India was to have its permanent headquarters inside the Bal Bhavan in New Delhi.

SECOND BREAKFAST: “The creative energies of our own time . . .”

PRABHA SAHASRABUDHE: It is important to discuss the philosophy behind the Children’s Art Carnival: that is, creative education. I think a creatively oriented philosophy of art education, one that supports new methods of teaching art, will in all possible ways facilitate the advancement of art education in Indian schools. The Children’s Art Carnival in India must “help assist in [the] transformation of a society by recognizing and establishing the creative energies of our own time.”30Sahasrabudhe, “A Conceptual Framework for a Children’s Art Education Center,” 136. The aim should be to develop an art education center as a base from which to introduce a philosophy of creative art education. “The philosophy of creative art education can be successfully introduced, demonstrated, and implemented where an atmosphere of freedom prevails, and where values such as respect for individual dignity, faith in individuality, and other democratic values, are generally accepted.”31Ibid., 6.

INDIRA GANDHI: I must confess I am attracted by the relationship between participatory democracy and education. But how does one bring it about?

PS: “Art education offers every individual an opportunity to partake in the bounty of cultural goods, and makes it possible for everyone to become culture-makers.”32Ibid., 24. A society that proposes to encourage aesthetic activity must provide an atmosphere in which personal uniqueness is recognized and take delight in the individual’s right to freedom. “What the Indian child needs most is recognition of his individuality, acceptance of himself as an individual in his own right, with a claim for a world of his own.”33Ibid., 23. It is the need for self-assertion, for self-realization. The need to be individual—the very survival of democracy depends on this.

IG: What I have been trying to do in India is to involve more people in the political processes and to initiate public discussions about education and other important subjects.

PS: “Art is an activity of the evolving human consciousness. A work of art is the manifestation, the symbolic image of man’s awareness of his relatedness to the external world and of his consciousness of his inner being.”34Ibid., 19. As the child engages in self-expression, he becomes aware of the possibilities and responsibilities of individual action.

IG: Why is creative education the right method to be introduced?

PS: Because it is within the context of creative education that the concept of freedom of the individual is cherished. Creative education derives its strength from the environment, from the values that the society upholds. The method behind such an education is a creative, constructive, and critical one. Sir Herbert Read has called it the method of “natural wisdom” and “the integral method.”35Sir Herbert Edward Read (1893–1968) was a British critic, art historian, and philosopher of education. He was a distinguished presence on museum boards, arts institutions, and university faculties. John Dewey terms it the approach of “creative intelligence.”36John Dewey (1859–1952) was an American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer. Dewey is one of the primary figures associated with the philosophy of pragmatism and is considered one of the founders of functional psychology. It is the method that integrates the intellectual and emotional, rational and intuitive, conscious and unconscious aspects of a child’s personality. It is the method that fosters creative intelligence as well as aesthetic sensibility. It is the method that combines the way the artist approaches a problem with the approach of the scientist.

IG: Pupul says it is important that the child does not lose his sense of wonder at the tremendous glory of everyday things—tender green shoots, the sun and the stars, the majesty of man and also his frailties. She also believes there has to be wonder and delight, reverence and frugality and cleaving attention. It is only then that the listening mind can take root in the child—the listening mind, which is in direct communication with art. Your references, Dewey and Read, are not Indian scholars.37Jayakar, “The Place of Children’s Museum in Art Education,” 7.

PS: References to the importance of art in education are not lacking in the writings of influential Indians. Creative activity is the basic principle of [Mahatma] Gandhiji’s nationally adopted scheme of Basic Education, for example.38The “Wardha Scheme of Education,” popularly known as “Basic Education,” was the first attempt at a national educational curriculum in British India. Its aim was to make the child self-reliant by ensuring that his acquired knowledge and skills would be of use to him in daily life.

IG: In bringing the Children’s Art Carnival to India, we need to infuse this creative way of doing things, with Indian thought.39Sahasrabudhe, interview by author, Pompton Lakes, New Jersey, 2019.

THIRD BREAKFAST: “Art is not a question of ownership, either of a country, or of a people.”

INDIRA GANDHI: The philosophy of creative education that sustains the Children’s Art Carnival derives from Western, and particularly American, educational sources. How does this American philosophy of creative education apply to India?

PRABHA SAHASRABUDHE: This question is appropriate and legitimate. My answer is that American education reflects the social structure of a free and fluid society—in that free, tax-supported schools are a concrete manifestation of these ideals. Creative education, an educational tradition in a free, liberal democratic society can very rightly be termed “democratic education,” rather than simply “American education.” An education that regards every individual as an end, and never as a means; an education that gives all children equal opportunity and that strives toward the liberation of the individual’s potential for creative, intelligent, and self-disciplined living; an education that generates a sense of interdependence between the individual and the society is not, in this researcher’s opinion, foreign in its spirit or in its temper to India. This is not to suggest that the structure or seeds of American art education can be transplanted to Indian soil as is, without consideration of certain local factors. We need to discuss creative education in the context of the aesthetic educational needs of Indian children, the characteristics of Indian culture, and the status of art education in Indian schools.40Sahasrabudhe, “A Conceptual Framework for a Children’s Art Education Center,” 85.

IG: Pupul explained to me that one of the burdens we carry is the method of art education brought to us [to India] by the British more than a hundred years ago. The separation of art from craft disciplines, and the type of teaching established for the training of art and craft teachers in art schools, has led to enormous waste of men and resources. Cadres of art teachers who are mediocre in terms of their vision, who are neither artists nor craftsmen nor communicators, have emerged. It is these teachers who are responsible for the child during the most formative periods of his life. This time, will we be carrying the burden of American education to the Indian people?41Jayakar, “The Place of Children’s Museum in Art Education,” 4.

PS: It is no wonder that the Children’s Art Carnival is an American idea, for I would assert that a museum can fulfill its educational promise only in an atmosphere of liberal and progressive ideas fostered by a democratic society. “It would take the constant enthusiasm of an awakened and enlightened community concerned with education of its growing generation of children, its faith in the uniqueness and dignity of the human being, its atmosphere of freedom and democracy to demonstrate the workability of this concept of museums as an instrument of children’s education.”42Sahasrabudhe, “A Blueprint for the National Children’s Museum,” 136.

IG: I’m concerned about how “craft has become a way of producing mediocre ornamental objects, cut away from the needs of the child and unrelated to the child’s environment. No attempt is made to make the child understand the materials he uses or the discipline inherent to his tools. Even before the child has gained control of the muscles of his hand and can hold a pencil, he is taught to copy drawings from a copy book on small pieces of paper. The child never has access to materials or spaces, such as a wall or a mud floor, where he can work on large surfaces. This narrowing of the child’s vision results in a general diminishing of the child’s basic capacity to perceive in a vast way.”43Jayakar, “The Place of Children’s Museum in Art Education,” 4.

Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941) was a Bengali polymath, poet, musician, and artist. On February 9, 1919, he delivered a lecture titled “The Centre of Indian Culture in Madras,” which dealt with what should be the educational ideal in India.PS: Following the ideas of [Gurudev Rabindranath] Tagore, in order for an art educational philosophy to become a valid educational theory for India, it must (1) be based on the fundamental beliefs of the people, shaped by their common heritage, (2) consider the aim of education, the growth and developmental stages of children, and the needs of children, and (3) understand the implications of this art education philosophy for the individual and the society.44Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941) was a Bengali polymath, poet, musician, and artist. On February 9, 1919, he delivered a lecture titled “The Centre of Indian Culture in Madras,” which dealt with what should be the educational ideal in India.

IG: For the Children’s Art Carnival to function effectively, it will have to concern itself with the training of a new type of art educator: a teacher who is sensitive, observant, and awake to the needs of the child and his environment. It is only through this process of observation, questioning, and learning that the teacher will find revealed those forms that are essential to the germination of a living art tradition.

PS: “Only by making culture a ‘live issue’ for every individual can India put itself in contact with the vital and life-giving qualities in her past.”45Sahasrabudhe, “A Conceptual Framework for a Children’s Art Education Center,” 24.

IG: But at the same time, Pupul has pointed out to me that among the factors the Children’s Art Carnival will have to stress is the need to break down the limiting concepts of national and local frontiers of art. “The child must understand that art is not a question of ownership, either of a country, or of a people.”46Jayakar, “The Place of Children’s Museum in Art Education,” 7.

Indira Gandhi left New York City by train after this meeting to receive the Howland Memorial Prize of Yale University for Distinguished Achievement. Sahasrabudhe and Gandhi continued their discussions in the following months. In 1961, after earning his doctoral degree, Sahasrabudhe moved to New Delhi with his wife, Sybil, and their first child, Kyra. In New Delhi, Sahasrabudhe took over as director of the Children Centers for Creative, Critical, and Constructive Education at the Bal Bhavan and National Children’s Museum. During this time, Sahasrabudhe prepared for the arrival of the Children’s Art Carnival, planned for 1963.

CODA: After three breakfasts . . . an elephant’s snack

On March 14 1962, Urvashi, “the baby elephant,” found herself at the Teen Murti House, the residence of Jawaharlal Nehru in New Delhi, to be fed by US first lady Jacqueline Kennedy. Kennedy’s good will in offering a snack to Urvashi is captured in images taken by Indian photojournalist Homai Vyarawalla as an awkward moment: candid in the first lady’s attitude and also the elephant’s dramatic response.47Homai Vyarawalla (1913–2012), commonly known by her pseudonym Dalda 13, was the first Indian woman to work as a photojournalist. The occasion of this episode was none other than the symbolic presentation of the Children’s Art Carnival to Indira Gandhi as “An American Gift to the Indian Child.” The “gift-giving” formula of the ceremony presented what had been a reciprocally shared search for answers in art education as an uneven cultural exchange. It, in fact, offered an image that can be read as not too different from the exchange between America’s first lady and Urvashi: the US dominant culture “feeding” a Western pedagogical experiment to a young postcolonial India.

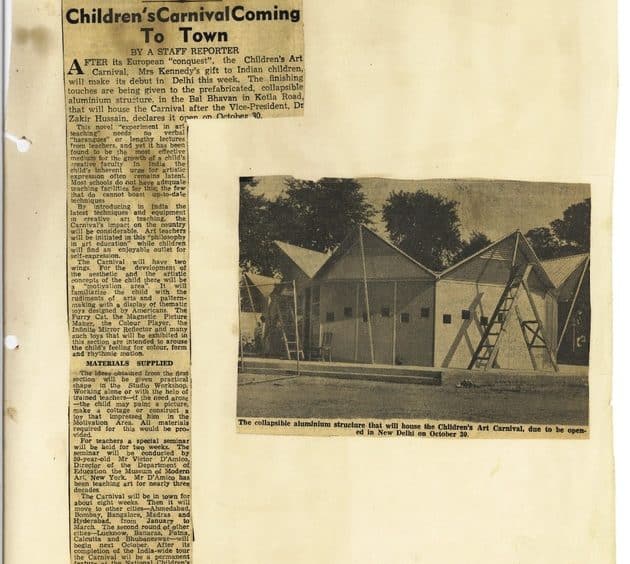

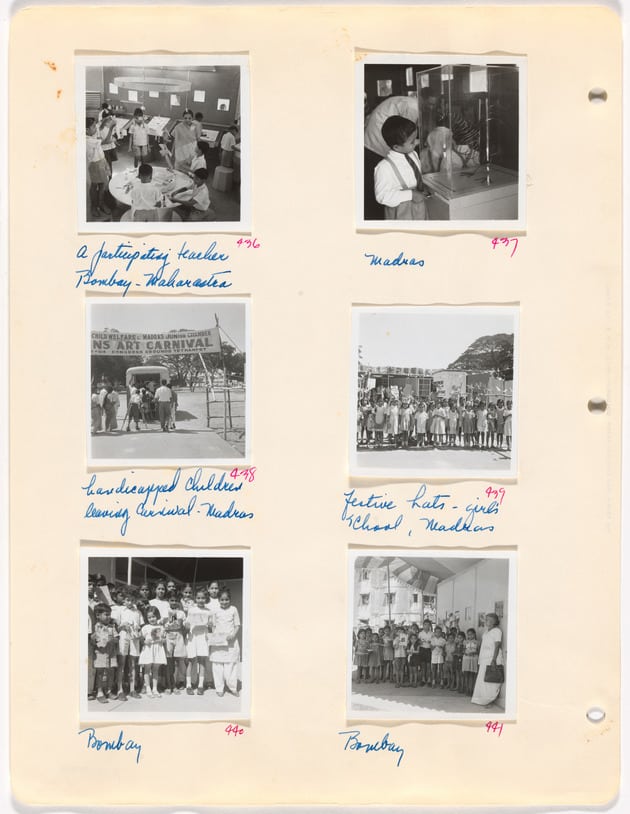

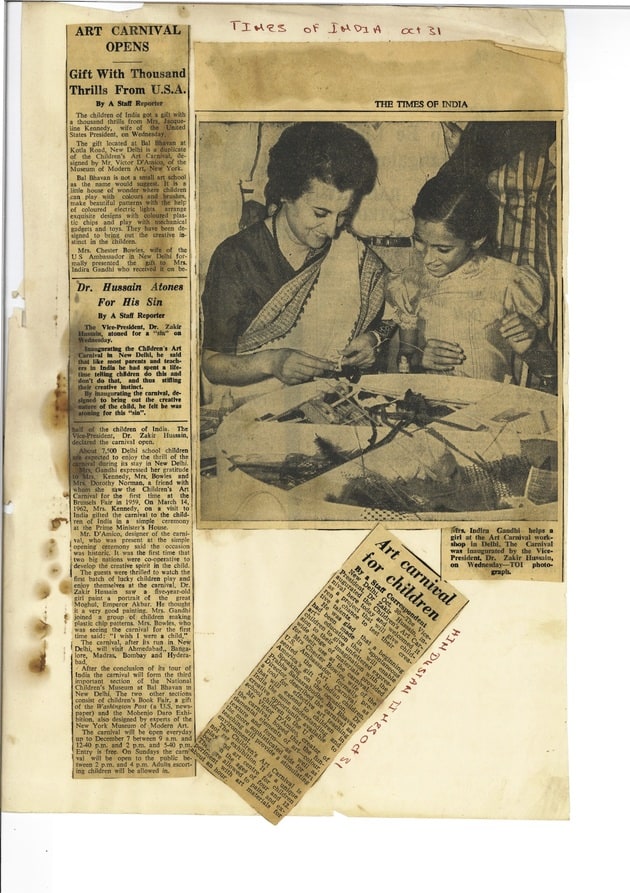

On October 30, 1963, Indira Gandhi inaugurated the Children’s Art Carnival in New Delhi. MoMA’s International Council, the Asia Society, MoMA’s Education Department, and individual donors provided the necessary funds for putting the Carnival in full motion. It had maintained its original two-part structure, with an inspirational area and studio workshop, and embodied Gandhi and Sahasrabudhe’s joint conviction that art education can create a new spirit in society through opportunities for creative development.

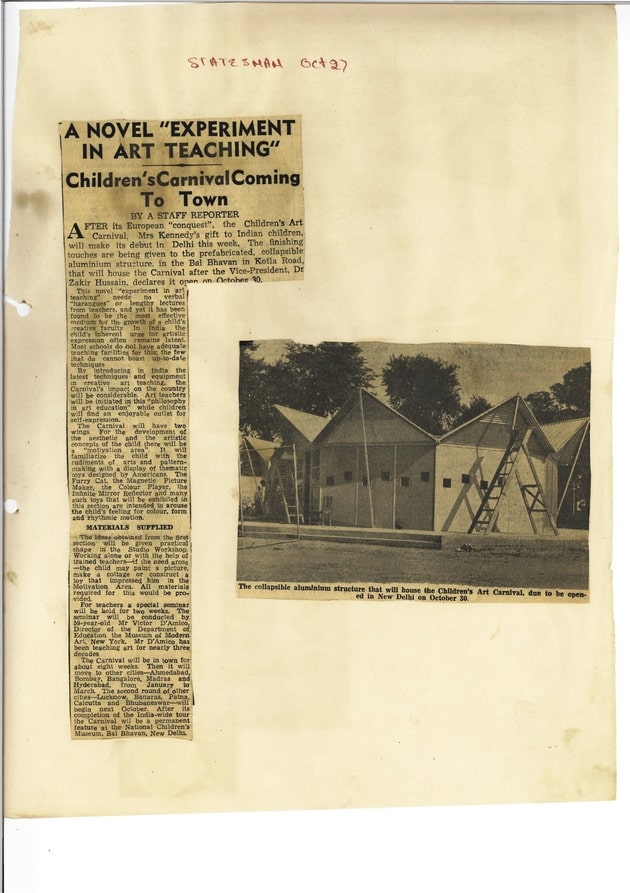

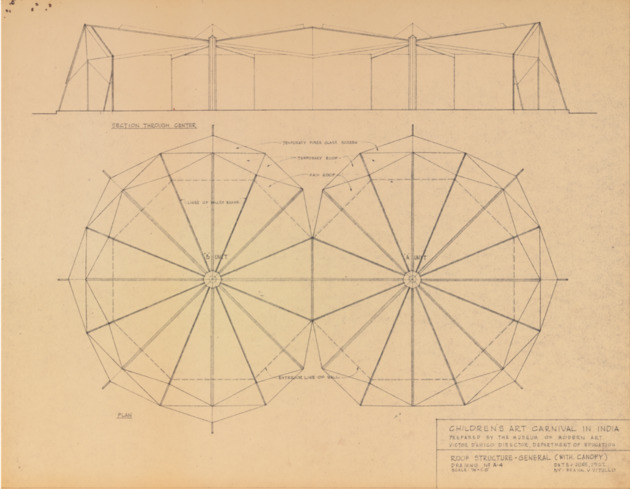

The Children’s Art Carnival in India was distinctively different from past US iterations. For the first time, the Carnival was to be housed entirely within its own structure. The building for the Carnival was designed to be portable and thus able to travel to different cities in India. The structure was fabricated in New Delhi from designs and working drawings by Frank Vitullo and Victor D’Amico. The Children’s Art Carnival in India was located in two octagonal rooms that were joined along one side that connected the motivational and studio areas.

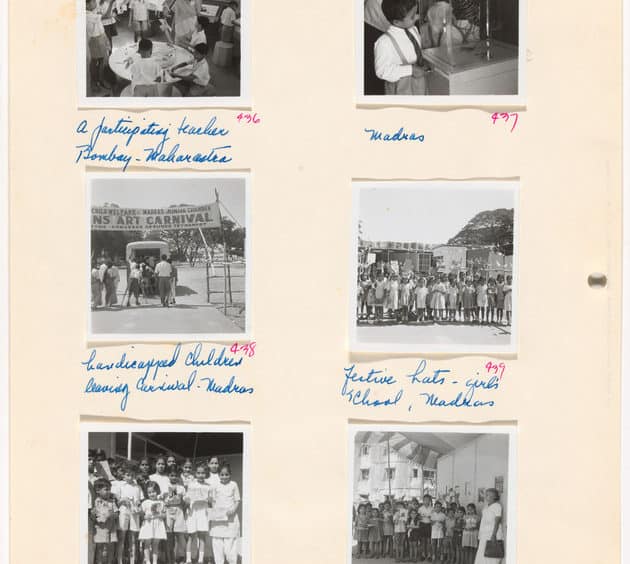

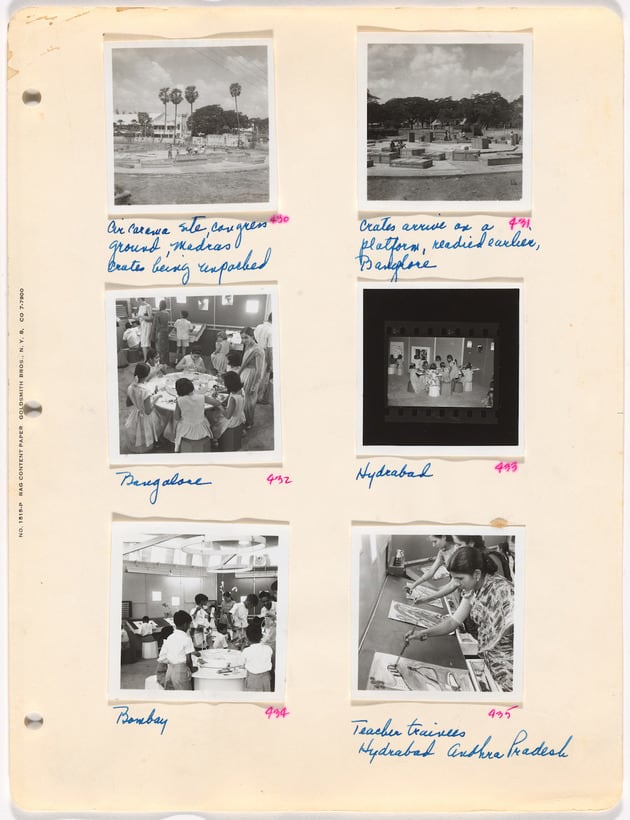

This portable design responded to Gandhi and Sahasrabudhe’s aim of taking the Carnival to different Indian contexts. The Carnival toured five cities in India: Hyderabad, Madras, Bangalore, Bombay, and Ahmedabad, before returning to New Delhi, where it was permanently installed in the National Children’s Museum.48Madras refers to the capital of Tamil Nadu, a state in south India. Madras was renamed Chennai in 1996.

This singular story of a leading politician sitting down with an art educator offers an opportunity to think about the importance of having policy makers and art education practitioners address key questions together. In my conversations with Dr. Prabha Sahasrabudhe, he remembered fondly: “I was just blessed with this opportunity. Indira Gandhi never, never, never said no to me. Never.”

The Children’s Art Carnival played, according to Sahasrabudhe, a small but vital role. It gave him and Gandhi a reason to meet and to tackle crucial questions that would permeate the field of art education. At a government level in India, the Children’s Art Carnival was a public acknowledgment that art education should promote creative thinking. At an institutional level, the most important consequence was the establishment of a permanent Carnival inside the Bal Bhavan and National Children’s Museum in New Delhi (with Sahasrabudhe as its director). This joint institution supported initiatives including Delhi’s first Art Teachers’ Conference, held in 1963, and followed by ongoing seminars and conferences in the ensuing decades that strengthened the art education research network in schools in New Delhi as well as established a teacher’s training program that (with transformations) exists today.

However, from the broader lens of art education in India, the impact of the Carnival dilutes. Many questions that arose in the conversations between Gandhi and Sahasrabudhe remain far from resolved: Is it possible (or even responsible) to devise an educational system that addresses the multiplicity of contexts that coexist in India? Is art a global language whose education can be outlined in all-inclusive terms? Is addressing democratic values part of what should be included in an art education curriculum? Is it acceptable to assume that democratic values in India and the United States are the same? How does self-assertion, self-realization, and the need to be individual translate into an awareness of the relatedness to the external world?

In this larger perspective, MoMA, the Children’s Art Carnival, or the day the US first lady fed Urvashi, “the baby elephant,” seem anecdotal. The Children’s Art Carnival in India was only a small event, “an elephant’s snack,” when compared to the important issues whose surface Sahasrabudhe and Gandhi had only begun to scratch over three breakfasts in 1960 at the Westbury Hotel in New York City.

The Bengal School of Art, commonly referred to as the Bengal School, was an art movement and style of Indian painting that originated in Bengal, primarily in Kolkata and Shantiniketan, and that flourished throughout India during the British Raj in the early 20th century. Also known as the “Indian style of painting” in its early days, it was associated with Indian nationalism and led by Abanindranath Tagore (1871–1951), but was also promoted and supported by British arts administrators such as E. B. Havell.

- 1Carmen Moersch, “Application: Proposal for a Youth Project Dealing with Forms of Youth Visibility in Galleries,” in Magic Moments: Collaboration between Artists and Young People, ed. Anna Harding (London: Black Dog, 2005), 198.

- 2Prabha Sahasrabudhe, interview by author, Pompton Lakes, New Jersey, 2019.

- 3Ibid.

- 4Modern Art for Young People [MoMA Exh. #279, February 21–March 11, 1945], Victor D’Amico Papers VI.50. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.

- 5Over the course of 22 years, there was fluctuation in the age range but 4 to 12 was most common.

- 6At the Brussels World’s Fair the Children’s Art Carnival was named Children’s Creative Center.

- 7Final Report: Children’s Creative Center. US Pavilion. Brussels World Fair 1958. Charles Henry Alston Papers, 1924–1980, Box 1, Folder 6. Archives of American Art, Washington DC.

- 8“Background Information—The Children’s Art Carnival.” International Council & International Program Records I.B.881. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.

- 9Victor D’Amico (1904–1987) was an American teaching artist and the founding director of the Department of Education of The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

- 10Pupul Jayakar née Mehta (1915–1997) was an Indian cultural activist and writer, best known for her work on the revival of traditional and village arts, handlooms, and handicrafts in post-independence India. She served as a cultural adviser to Indira Gandhi. At the request of Jayakar, officials from the Government of India approached Sahasrabudhe in September 1960 to request he submit a plan for an “Art Education Center” that the Government was considering sponsoring.

- 11Indira Gandhi, Indira Gandhi, Letters to an American Friend (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1985), 75.

- 12Sahasrabudhe had been told that the museum was confirmed, but in fact, it wasn’t. When he arrived in Delhi a year later to assume the role of museum director, there was no building or museum to direct.

- 13Jawaharlal Nehru (1889–1964) was the first prime minister of India and a central figure in Indian politics before and after independence.

- 14Artek, a youth camp on the Black Sea, was one of the most prominent examples of how Soviet pedagogues and architects collaborated to create educational institutions for children. It aimed at uniting children from all over the Soviet Union to share an outdoor, or “pioneer” experience, within the natural environment. As prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru visited the camp during his first official visit to the USSR in 1955.

- 15Gandhi, foreword to Museums for Children—A Seminar: Why, What and How? (New Delhi: Bal Bhavan and National Children’s Museum New Delhi, 1962), vii.

- 16The attainment of independence in India led to changes in the Indian educational setup. The process of addressing the growing demands of education as a consequence of industrialization and modernization was called the “Educational Reconstruction.”

- 17Gandhi, foreword to Museums for Children, viii.

- 18Indira Gandhi, Indira Gandhi, Letters to an American Friend (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1985), 138.

- 19Ibid., 14.

- 20On August 15, 1947, the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed the Indian Independence Act, transferring power to the constituent assemblies. Quote from Gandhi, Indira Gandhi, Letters to an American Friend, 138.

- 21Prabha Sahasrabudhe, “A Conceptual Framework for a Children’s Art Education Center, in New Delhi, India” (PhD dissertation, New York University, 1961), 7.

- 22The Ajanta Caves are 30 rock-cut Buddhist cave monuments that date from the 2nd century BCE to about 480 CE. They are located near Ajanta village in the Aurangabad district of Maharashtra state in western India. Since 1819, many attempts have been made to document the paintings inside them. From 1872 to 1885, John Griffiths, principal of the Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy School of Art, and seven students spent every winter at the caves, producing approximately 300 copies of the paintings within.

- 23Pupul Jayakar, “The Place of Children’s Museum in Art Education,” in Museums for Children, 5.

- 24The term “indoctrinary” is commonly used in the field of art education to refer to practices that potentially hamper creative activity. Sahasrabudhe’s definition of indoctrinary methods in children’s education include fostering competition, encouraging imitation, and allowing expectations from adults (with the exception of trained teaching artists) to interfere with the individual development of the child.

- 25Sahasrabudhe, “A Conceptual Framework for a Children’s Art Education Center,” 3.

- 26Prabha Sahasrabudhe, “A Blueprint for the National Children’s Museum,” in Museums for Children,” 141.

- 27Gandhi, Indira Gandhi, Letters to an American Friend, 137.

- 28Dorothy Norman (1905–1997) was an American photographer, writer, editor, arts patron. Gandhi met Norman in New York in 1956, and the two developed a friendship that was to continue throughout their lives.

- 29Victor D’Amico, “The Children’s Art Caravan: Creative Education on Wheels,” in Arts and Activities: The Teacher’s Arts and Crafts Guide(1970), Victor D’Amico Papers, IV.C.7, pp. 13–19. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.

- 30Sahasrabudhe, “A Conceptual Framework for a Children’s Art Education Center,” 136.

- 31Ibid., 6.

- 32Ibid., 24.

- 33Ibid., 23.

- 34Ibid., 19.

- 35Sir Herbert Edward Read (1893–1968) was a British critic, art historian, and philosopher of education. He was a distinguished presence on museum boards, arts institutions, and university faculties.

- 36John Dewey (1859–1952) was an American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer. Dewey is one of the primary figures associated with the philosophy of pragmatism and is considered one of the founders of functional psychology.

- 37Jayakar, “The Place of Children’s Museum in Art Education,” 7.

- 38The “Wardha Scheme of Education,” popularly known as “Basic Education,” was the first attempt at a national educational curriculum in British India. Its aim was to make the child self-reliant by ensuring that his acquired knowledge and skills would be of use to him in daily life.

- 39Sahasrabudhe, interview by author, Pompton Lakes, New Jersey, 2019.

- 40Sahasrabudhe, “A Conceptual Framework for a Children’s Art Education Center,” 85.

- 41Jayakar, “The Place of Children’s Museum in Art Education,” 4.

- 42Sahasrabudhe, “A Blueprint for the National Children’s Museum,” 136.

- 43Jayakar, “The Place of Children’s Museum in Art Education,” 4.

- 44Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941) was a Bengali polymath, poet, musician, and artist. On February 9, 1919, he delivered a lecture titled “The Centre of Indian Culture in Madras,” which dealt with what should be the educational ideal in India.

- 45Sahasrabudhe, “A Conceptual Framework for a Children’s Art Education Center,” 24.

- 46Jayakar, “The Place of Children’s Museum in Art Education,” 7.

- 47Homai Vyarawalla (1913–2012), commonly known by her pseudonym Dalda 13, was the first Indian woman to work as a photojournalist.

- 48Madras refers to the capital of Tamil Nadu, a state in south India. Madras was renamed Chennai in 1996.