In this essay, Karolina Majewska-Güde explores the history of Galeria Adres, which the feminist Polish artist Ewa Partum launched in Łódź in 1972. Through unrivaled access and meticulous attention to the materials in the artist’s personal archive, Majewska-Güde reveals the role of this avant-garde gallery in fostering conceptual art with an international reach during the period of state socialism in Poland. The author is also a curator of the exhibition ewa partum: my gallery is an idea , realized in cooperation with Berenika Partum, which opened in Warsaw on March 7, 2019.

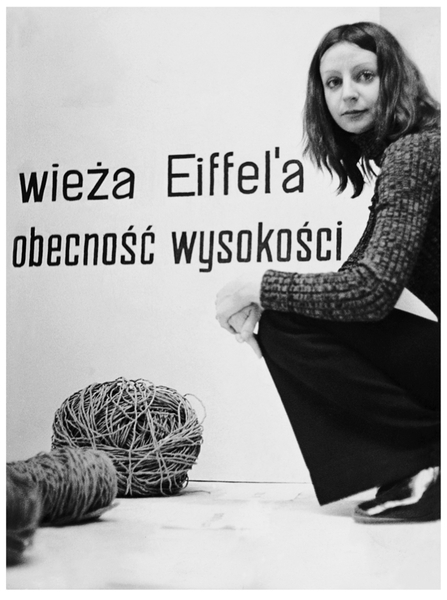

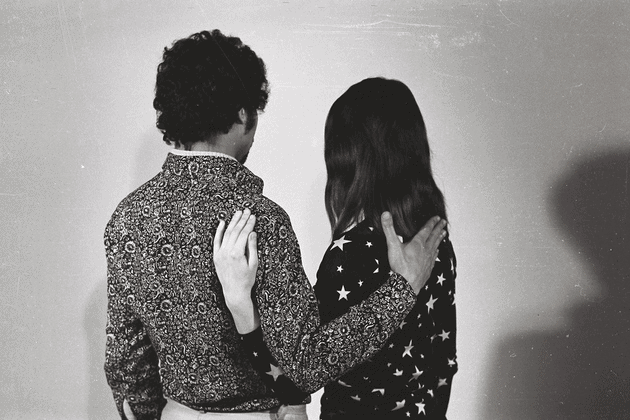

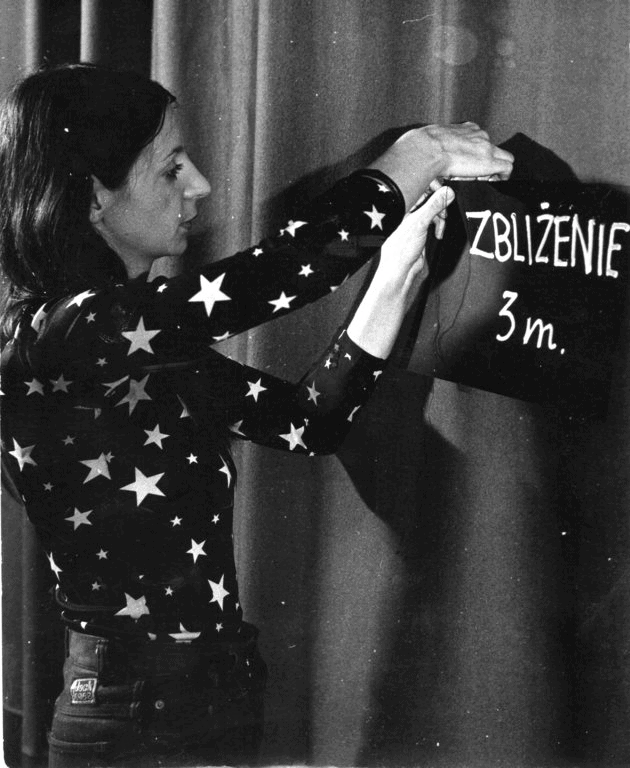

Polish-born artist Ewa Partum is considered a pioneer of Eastern European feminist art produced within the conceptual idiom. Her work belongs to two discursive formations: the historical neo-avant-garde that emerged during the 1960s and contemporary art with its temporal and semantic transition before and after 1989. Partum’s work can also be chronologically divided into Polish (1965–82), West Berlin (from 1982–89) and transnational/global (post-1989) periods. Undoubtedly, the relative visibility of Partum’s practice in Poland throughout the 1970s was due not only to her active engagement and participation in the existing artistic networks and events, but also to the creation of art infrastructure (Galeria Adres) and to her own flexibility as a cultural producer, which we can retrospectively define as artist as curator, artist as producer, and artist as publisher.

This paper seeks to articulate the history of Ewa Partum’s Galeria Adres (1972–77) in Łódź, which she operated from the aforementioned strategic positions. My inquiry focuses on the role of Galeria Adres in terms of specific locales and contexts (both Polish and Eastern European), and considers 1) its structure and artistic profile; 2) its transnational aspirations and strategies; and 3) Partum’s strategy of appropriating infrastructure as a part of her artistic practice.1The Archive of the Galeria Adres has not been preserved in its entirety. My analysis is, therefore, based on a close examination of the remaining fragmentary material, which includes correspondence, mail art, books, catalogues, brochures, posters, experimental film scores, and notes. I also refer to art historical texts and especially to Dorota Monkiewicz’s essay published in 2015 (“On the International Artistic Exchange Network in Poland as Illustrated by the Example of Łódź’s Adres Gallery,” in Nothing Stops the Idea of Art, ed. Maria Morzuch, exh.cat. [Łódź: Muzeum Sztuki, 2015], 56–67), which constitutes the first attempt to historize the Galeria Adres’s activities. My knowledge of the gallery’s activities was also enriched by a series of interviews with Ewa Partum, Marek Żychski and other participants of the gallery activities, that I conducted during my doctoral dissertation’s research over the past 5 years. Before reconstructing the history of the Galeria Adres, I would like to present some introductory remarks regarding cultural politics in Poland in the 1970s, focusing in particular on the problem of the structural dependency of artist-run, so-called independent galleries on state patronage.

“Art-Infrastructure-in-the-Making.”2The notion of “art-infrastructure-in-the-making” was introduced by Irit Rogoff in a lecture delivered at the Former West Congress Documents, Constellations, Prospects, which took place March 18–24, 2013, at Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin. A recording of the lecture is available at http://www.formerwest.org/DocumentsConstellationsProspects/Contributions/Infrastructure.

The decade 1970–80 was a time in Polish political and culture history characterized by a relative opening to the West, which fuelled proto-consumerist attitudes. After the political crisis of 19683The Polish 1968 political crisis, known as “March 1968,” pertains to a series of protests against the Communist government that paralleled the Prague Spring. These protests were instrumentalized in orchestrating an anti-Semitic (branded anti-Zionist) campaign related to the power struggle within the Polish Communist Party. The anti-Jewish smear campaign, propaganda, mass mobilization, and continuous harassment resulted in the emigration of 13,000 citizens of Jewish descent., and the reshuffle resulting in Edward Gierek’s becoming head of the Polish Communist Party (on December 20, 1970), the country gradually became de-ideologized.4Edward Gierek remained in power for almost ten years, from December 20, 1970, to September 6, 1980. As a result of the new cultural politics, artistic culture in the 1970s functioned relatively freely within the official and alternative infrastructures but was nonetheless “limited, controlled and not stimulated.”5Piotr Piotrowski, Dekada: O Syndromie Lat Siedemdziesiątych, Kulturze Artystycznej, Krytyce, Sztuce-Wybiórczo i Subiektywnie(Poznań: Obserwator, 1991), 20. Consequently, as art historian Piotr Piotrowski has proposed, it is not accurate to describe the Polish cultural landscape in the 1970s as two separated circuits of culture: the official circle, which promoted apolitical post-thaw modernism, and the nonofficial neo-avant-garde circle, or—as more recently referred to in the context of Eastern European scholarship—the first and the second public spheres.6See, for example, the recently published comprehensive joint publication that frames neo-avant-garde art from Central-Eastern Europe within the concept of the second public sphere: Katalin Cseh-Varga and Adam Czirak, eds., Performance Art in the Second Public Sphere: Event-Based Art in Late Socialist Europe (New York: Routledge, 2018). It would instead be more accurate to map neo-avant-garde practices in the margins of official culture, or to visualize them as connected to the mainstream through the system of sponsorship and censorship.7Piotrowski also observed that apart from political reasons, the marginalization of neo-avant-garde art was related to pragmatic problems: a lack of strong (central) art institutions to promote neo-avant-garde values, as well as the mere incompetence of civil servants whose decisions were shaping the Polish cultural scene. See Piotrowski, Dekada, 20.

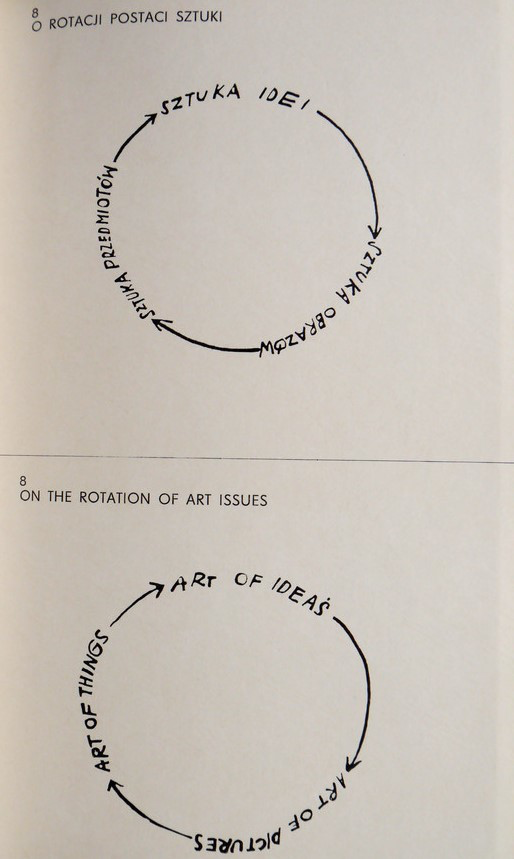

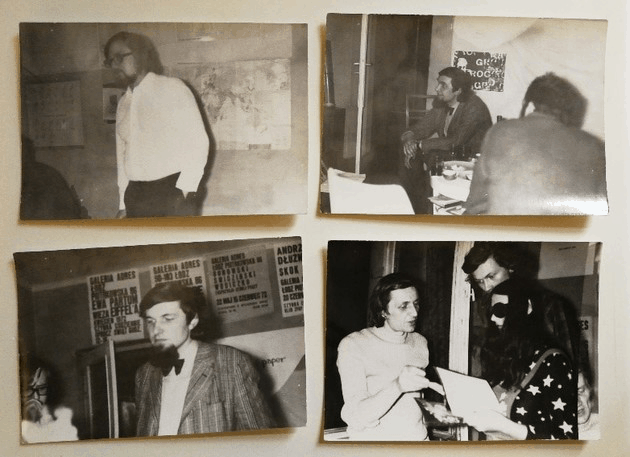

The beginning of the 1970s saw not only the number of artist-run art institutions rapidly increase, but also the development of a new paradigm of art infrastructure. The monographer of the Polish art scene of the 1970s Marcin Lachowski argues that the dominant model of the art gallery in 1960 as an “art laboratory” or “autonomous artistic sphere” was replaced by a type of institution that problematized its own institutional entanglement.8Marcin Lachowski, Awangarda wobec instytucji. O sposobach prezentacji sztuki w PRL-u (Lublin: Towarzystwo Naukowe KUL 2006), 118–19. These institutions facilitated new formulas of art that could be characterized by a general tendency to replace the work of art as an object with its documentation: conceptual art, mail art, and Fluxus-related projects with their processual character, ephemerality, and hybridity; forms combining text, photography, action, and body. These artistic practices were easily produced and disseminated within more ephemeral, weaker structures. In that context, acting personas/active agents and personal connections, meetings, discussions, exchanges, and gestures became constitutive elements of art production.

An active participant in the neo-avant-garde movement, the influential art theorist Jerzy Ludwiński emphasized that the most important ways of stimulating the neo-avant-garde art movement in Poland in the 1970s were via the artists’ meetings, art seminars, and “independent galleries” that took place and/or were located in all parts of Poland. All of these “institutional inventions,” as he called them, constituted a system of distribution and presentation of art, but also “an educational platform, a system for the exchange of information on new forms of art.”9Jerzy Ludwiński, “Awangarda awangardy,” in Jarosław Kozłowski, (ed.): Sztuka w epoce postartystycznej i inne teksty (Akademia Sztuk Pięknych w Poznaniu, Biuro Wystaw Artystycznych we Wrocławiu, Poznan and Wroclaw 2009) 72-77, p.74. Ludwiński’s text was originally published in the journal Nadodrze no. 19 (1971). To characterize this dynamic institutional formula of the Polish neo-avant-garde as described above I appropriate the notion of “infrastructure-in-the-making” introduced in 2013 by Irit Rogoff in her lecture at the Former West Congress with respect to contemporary art practices.10Rogoff, lecture delivered at Documents, Constellations, Prospects. In my reading of the Polish neo-avant-garde art scene, I have found that this concept provides an adequate mode for conceptualizing the ways in which the art infrastructures functioned in the 1970s in that it captures “the move from properly functioning structures that serve to support something already agreed upon, to the recognition of ever-greater numbers of those who have a stake in what they contribute to or benefit from.”11Ibid. In other words, “infrastructure-in-the-making” of the Polish neo-avant-garde was constituted through conversations and exchanges of ideas and materials between artists and art critics and art theoreticians, which became more important for the process of art production than the actual physical parameters such as venues or technical support. Although partially infiltrated by the secret police,12See, for example, Jarosław Jakimczyk, Najweselszy Barak w Obozie: Tajna policja komunistyczna jako krytyk artystyczny i kurator sztuki w PRL-u (Warsaw: Akces 2015). this “infrastructure-in-the-making” was functioning as a relatively free sphere in terms of artistic deliberation.

Ewa Partum’s Galeria Adres, as I will demonstrate below, followed this paradigm not only by focusing on fostering artistic exchange but also by merely existing as a reciprocity between her and the other cultural producers who represented a transnational neo-avant-garde art.

The Artistic Profile of the Galeria Adres in Two Locales13Considering the spatio-temporal significance of the local, Elspeth Probyn distinguishes between “locale” and “location,” defining “locale” as a place that is the setting for a particular event: “A place understood as both a discursive and non-discursive arrangement that holds an even.” See locale Elspeth Probyn, “Travels in Postmodern: Making Sense of the Local,” in: Linda J. Nicholson, (ed.): Feminism/Postmodernism (New York and London, Routledge 1990), 76-189, p.178.

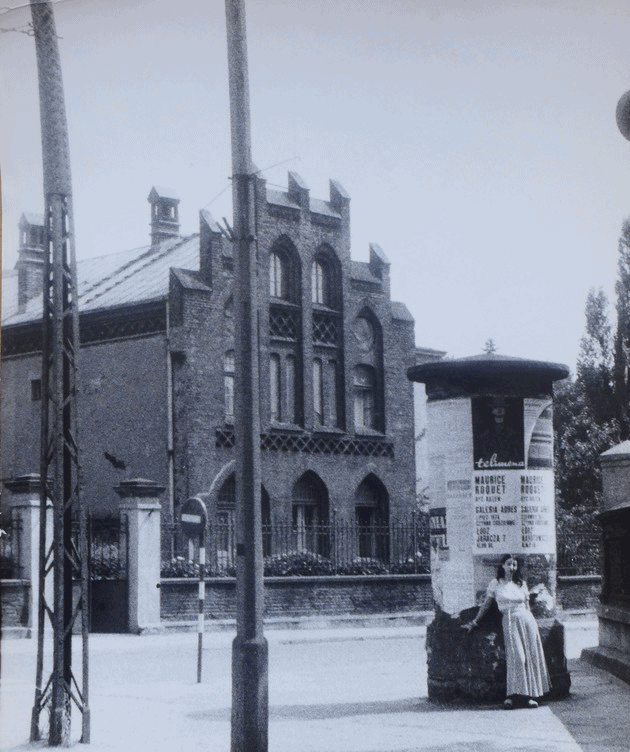

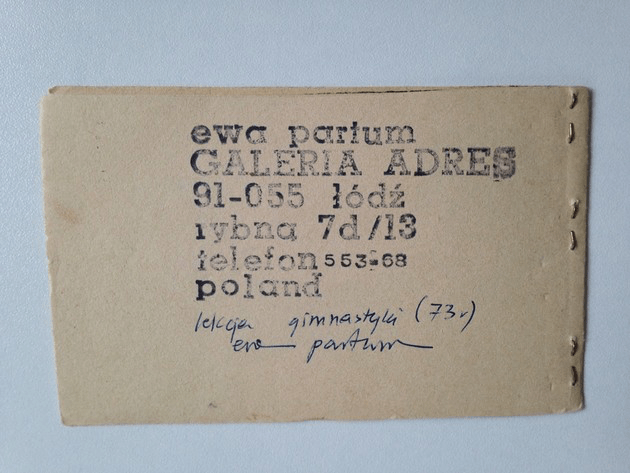

Ewa Partum founded the Galeria Adres in spring 1972 in Łódź, where she moved from Warsaw in 1971, and initially located her gallery in a small space (four square meters, or approximately forty-three square feet) under the steps of the offices of the Association of Polish Artists (Związek Polskich Artystów Plastyków, or ZPAP). The “independent art galleries” of the 1970s that existed parallel to the official exhibition system controlled by ZPAP were often created as attachments to official cultural institutions, such as student clubs, local cultural centers, and sometimes offices or factories. The aim of the neo-avant-garde artists was not to undermine the hosting institutions by subversive practices, but rather to exploit their institutional possibilities without initiating a dialogue. Being connected to an official institution increased the chances of obtaining occasional financial support as well as enabled access to printing facilities.

Partum’s strategy, however, was more akin to the contemporary practices described by Rogoff, who has argued with regards to socially engaged art that “much of the more activist-oriented work within the art field has taken the form of re-occupying infrastructures: using pre-existing spaces and technologies, budgets and support staffs, and recognized audiences in order to do something quite different.”14Rogoff, lecture delivered at Documents, Constellations, Prospects. Partum embraced the interventional strategy of a direct engagement with the institutional situatedness of the Galeria Adres. The artist chose a very particular fragment of the art infrastructure, the official Association of Polish Artists, and performed an “asignifying rupture”15In A Thousand Plateaus, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari list a series of characteristics of the rhizome as the principles of connection and heterogeneity, multiplicity, assignifying rupture, cartography, and decalcomania. The principle of assignifying rupture means that “a rhizome may be broken, shattered at a given spot, but will start up again, on one of its old lines, or on new lines.” Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, 2nd ed. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 303. by “doing something quite different” to the program and values represented by it. It must be emphasized that Partum’s choice of venue was not that unusual: the year before, ZPAP provided other artists with opportunities to present their conceptual activities in the club located within the ZPAP building, namely the conceptual galleries 80 x 140 and A4.16At the beginning of the 1970s, Łódź had become a place where conceptual activities could be realized within the framework of art galleries. In May 1971, the conceptual art gallery 80 x 140 was founded there, initiated by Jerzy Treliński with a flash card indicating the space’s measurements. The gallery’s activities took place inside the ZPAP building, as well as outside of it. From May 1972, the gallery coexisted with the gallery A4—namely a piece of paper in the A4 format with the name of the gallery inscribed on it by Andrzej Pierzgalski. To place a gallery within the official ZPAP offices meant to be granted relative visibility, and access to a professional audience as well as the status of a recognized art venue.

Partum thematized the situatedness of the Galeria Adres (under the steps of the Artist’s Association) through her artistic intervention, which challenged the integrity of the hosting institution. It was her first (undocumented) realization at the gallery, and it consisted of the action of wrapping portraits of ZPAP members, which were exhibited on the walls of the corridor. She accompanied her intervention with the following statement: “The field of artistic action / Instead of representing and representation (the mutual adoration of each other), requires an action in a broader sense.”17The original text reads, “Pole działania artystycznego / Zamiast reprezentacji i reprezentowania / (wzajemnej adoracji siebie samych) / wymaga działania artystycznego w szerszym sensie” (1972). “A Filed of Artistic Action/ Instead of Representation and Representing (a Mutual Adoration) / Demands an Artistic Action in a Broader Sense.” This form of intervention was not a self-centred institutional critique, or a critique of the historicity of a gallery/museum concept that could be applied to any cultural institution with the disposal of cultural capital. Rather, this was a guerrilla-style intervention that risked destabilizing the Galeria Adres’s own institutional position within the ZPAP organism. This policy, together with the conceptual aesthetics and transnationalism promoted by Partum, eventually lead to the eviction of the gallery from the ZPAP building the following year.

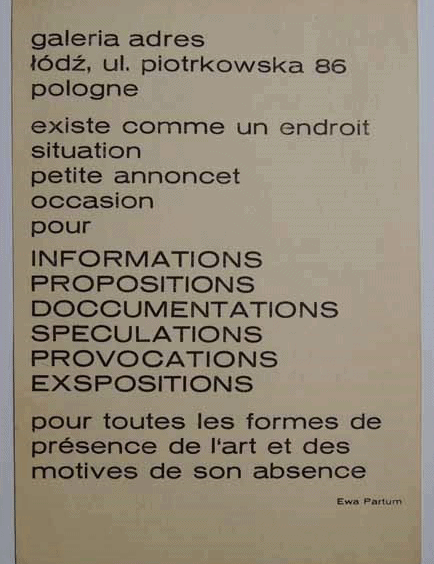

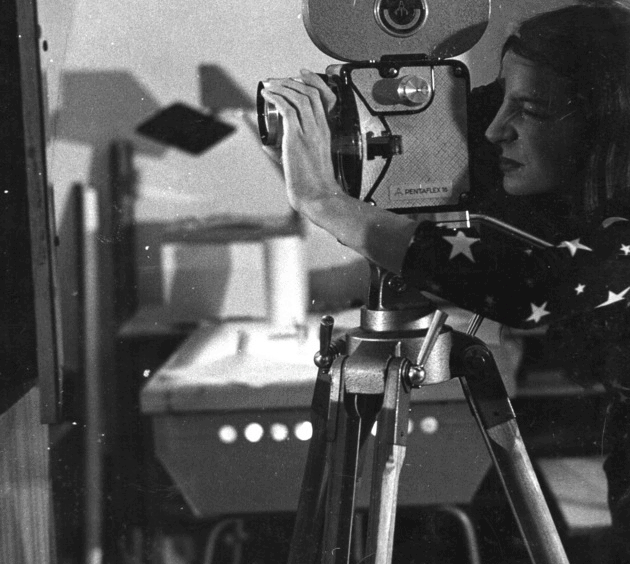

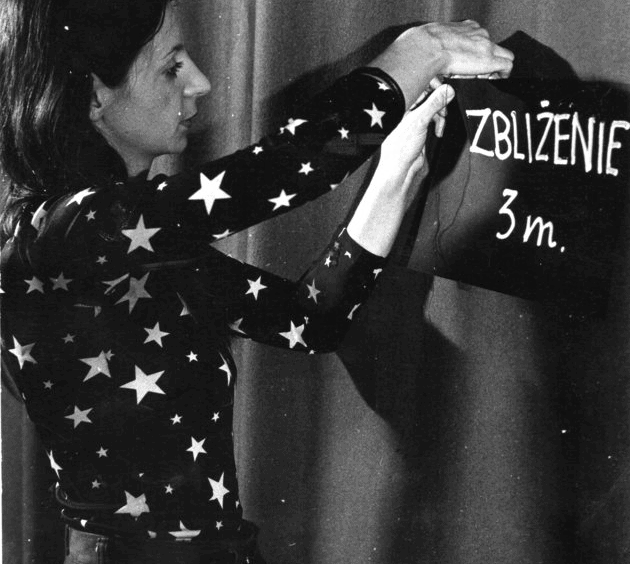

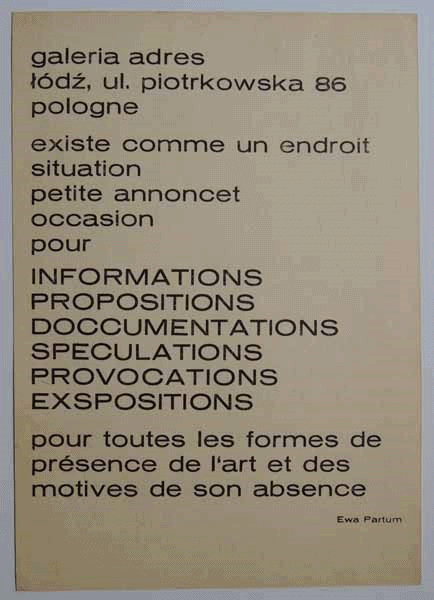

In her manifesto published in Polish and French and sent to institutions and artists in Poland and abroad,18At the beginning of the 1970s in Poland, French was still considered an international language, but in 1972, Ewa Partum began using English in the titles of her works and publications. Partum’s texts were originally written in Polish and translated by her collaborators Marek Żychski (English translator), Kader Lactta and Rolland Paret (international students from the Łódź Film Academy), and Ewa Zając (Partum’s friend and collaborator.) Partum defined the Galeria Adres as “a place, a situation, an opportunity, an offer, for information, proposition, documentation, speculation, provocation, exposition”19In 1971, Partum published a gallery manifesto that was republished in 1972 in Notatnik Robotnika Sztuki/Art’s Worker Notebook, an art zine published by Galeria ELin Elbląg. following the anti-institutional paradigm. In a video documentation realized by the local branch of the national TV in 1971–72, the artist emphasized the importance of art theory to her practice.20Ewa Partum, Galeria Adres Documentation (Łódź: TVP, 1971–72), 3 min. 36 sec., 8 mm, http://post.at.moma.org/sources/30/publications/287?_ga=2.134658353.1596660259.1523983044-774675610.1512302028. She mentioned that the aim of the gallery was to maintain contact with leading art theoreticians such as Andrzej Kostołowski in Poland, László Beke in Hungary, and Klaus Groh in West Germany.21Klaus Groh’s influential publication (Klaus Groh, Aktuelle Kunst in Osteuropa: CSSR, Jugoslawien, Polen, Rumänien, UdSSR, Ungarn [Cologne: DuMont, 1972]), did not include Ewa Partum’s practice. In 1972, using ZPAP facilities without requesting permission from the organization, Partum self-published Theses on Art No 1–17, a seminal text on conceptual art by Kostołowski, which Dorota Monkiewicz has argued remains one of the most important historical texts on conceptual art written in Polish.22Monkiewicz, “On the International Artistic Exchange Network in Poland as Illustrated by the Example of Łódź’s Adres Gallery,” 61.

Thus, significantly, as much as initiating and preserving contacts with artists and critics around the world, Partum focused most of her efforts on publishing activities and the production of documentation. Because there was no “absolute proliferation”23Jean Baudrillard, “Beyond the Vanishing Point of Art” (1988), quoted in Alexander Alberro, Conceptual Art and the Politics of Publicity(Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003), 150. in the Polish (or, broader Eastern European) context of the 1970s, but rather a scarcity of alternative culture, partly related to the limitations of the supply of paper for publishing books and magazines, self-published texts, catalogues, photographs, or posters assumed an aura akin to art objects, even before they had been validated by the global art market as such (after 1989). The “homogenisation of material and experience in the ubiquitous display of information”24Sjoerd van Tuinen and Stephen Zepke, introduction to Art History after Deleuze and Guattari, eds. Sjoerd van Tuinen and Stephen Zepke (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2017), 17. did assume in communist states a very political meaning: self-publishing (samizdat) had a political dimension as an activity associated with civil society and insubordination, even in cases when the publications did not have explicit political content.

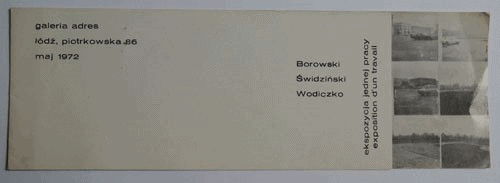

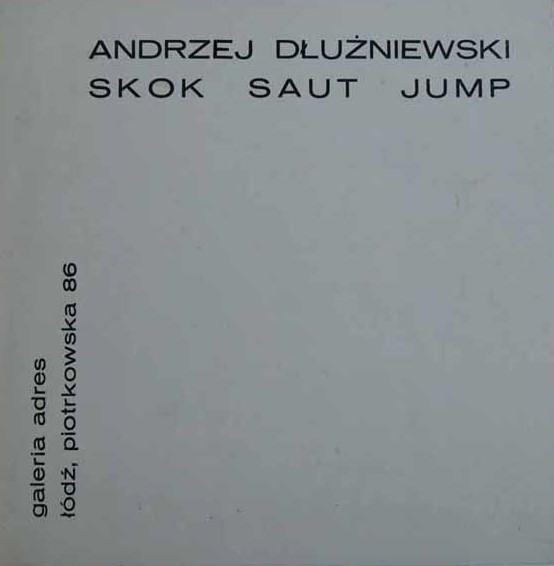

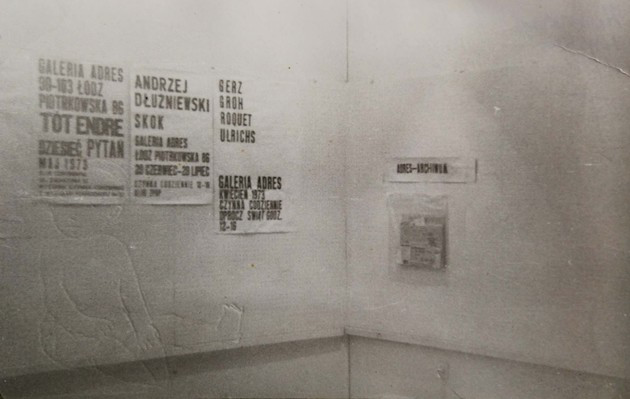

The exhibitions that took place at the Galeria Adres in the ZPAP office in 1972 were mostly related to media-oriented conceptualism and included projects by artists such as Krzysztof Wodiczko, Włodzimierz Borowski, Jan Świdziński, Andrzej Dłużniewski, Zbigniew Warpechowski, and Partum. At the beginning of 1973, Partum realized her first international project in collaboration with Jochen Gerz, presenting the exhibition Documentation of Recent European Art (Jochen Gerz, Klaus Groh, Maurice Roquet, and Timm Ulrichs). However, on March 14, 1973, a year after the gallery’s opening, the presidium of the local ward of ZPAP decided to close it. This decision was communicated as a recommendation of the general board of ZPAP to stop supporting “the dissemination of activities carried out nationally and also internationally.”25In the Galeria Adres Archive, there is a letter of support that was initiated by Partum and signed by many culture producers, including art historians and artists related to the neo-avant-garde art movement such as Józef Robakowski, Wojciech Bruszewski, Paweł Kwiek, and Ryszard Waśko.

Piotr Piotrowski, in his polemical text published in 1991, which he characterized as “subjective and selective,” argued that the poor quality of the art produced in the 1970s in Poland was related directly to the system of financing culture because art production’s dependence on state or municipal patronage reinforced attitudes of self-censorship.26Piotrowski, Dekada, 20. Partum’s strategy for the Galeria Adres consisted of using her own private means, namely her inheritance from her deceased father, and only occasionally seeking out and obtaining the public funding that the Communist state offered for “independent” culture initiatives. The Galeria Adres was, therefore, neither structurally nor financially dependent on the official system. For this reason, it was not possible for the gallery to be closed down by the authorities.

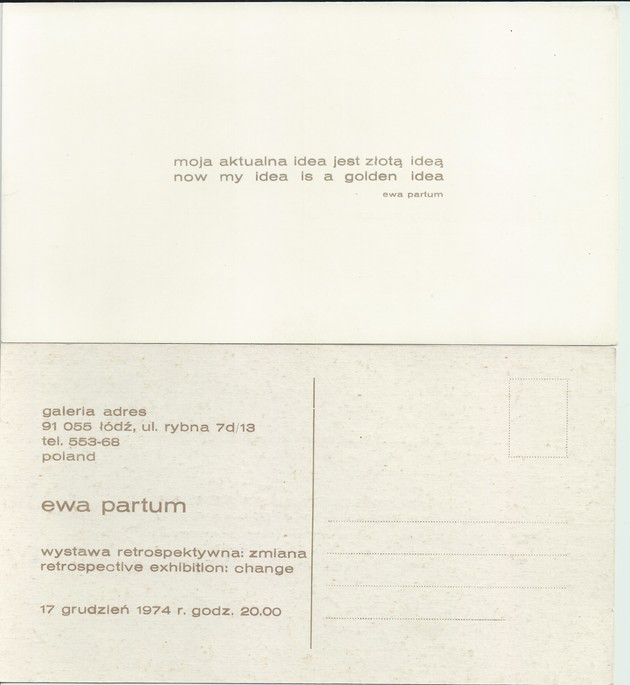

Instead of closing the Galeria Adres, as was recommended by the ZPAP presidium, Partum decided to increase her own level of financial support of the project. The artist moved the gallery to her mother’s apartment on Rybia Street, where she was living at the time, thus becoming independent from the venue provided by ZPAP. In a subsequent statement, preserved as a handwritten note in the Ewa Partum Archive, the artist appropriated a new infrastructural context and declared the Galeria Adres to be an integral part of a private apartment. The artist emphasized, however, that she was not inscribing her gallery into the tradition of the art salon, but rather seeking a sphere in which to explore the coexistence of life and art, private and public. She concluded her statement by declaring, “my gallery is a home.”27“Moja galeria jest domem”/ “My Gallery is a Home,” a handwritten and undated note in the Ewa Partum Archive. Thus, with her new statement, Partum thematized and explored the relationship between art and the everyday, where “the everyday” was conceptualized as a mode of being rather than as a form of activity. The Fluxus project of dissolving art into life or of learning to cherish aesthetic pleasure in the everyday was not at the core of this aesthetic program. According to the Partum’s artistic statement, “the everyday” is merely a sphere incompatible with bureaucracy and management. In other words, existing within the sphere of the everyday meant that the gallery was independent from the authorities. By exclaiming, “my gallery is a home,” the artist referred to the notion of individual, but not necessarily aesthetic, experience.28A discourse on the privacy of aesthetic experience was introduced into Polish conceptual art practices later on, in exhibitions such as Private Views (1978) or Individual Mythologies (1980), in which art is defined as a sphere of privacy in accordance with the individual character of aesthetic experience. See Luiza Nader, Konceptualizm w PRL, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego and Fundacja Galerii Foksal, Warszawa, 2009, 182. Thus, once it was relocated to Partum’s apartment, the gallery was re-inscribed within the discourse of privacy and experience that reinforces the idea of freedom from the official doctrine. As Piotr Piotrowski has argued, the independent art galleries of the 1970s produced meanings of art through the play of contexts.29Piotr Piotrowski, Znaczenia modernizmu: W stronę historii sztuki Polskiej po 1945, 2nd ed. (Poznań: Dom Wydawniczy Rebis, 2011), 211. In the case of Partum’s gallery, this strategy assumed a particular and ambivalent form. On the one hand, the artist positioned her gallery from the outset as an institution thematizing its situatedness, an idea also reflected in the gallery’s name (Galeria Adres).30Galeria Adres translates as “Address’ Gallery.” On the other hand, the Galeria Adres was conceptualized not as a particular locale, but rather as an event that manifested itself through a strong visual identification that was designed by Partum.

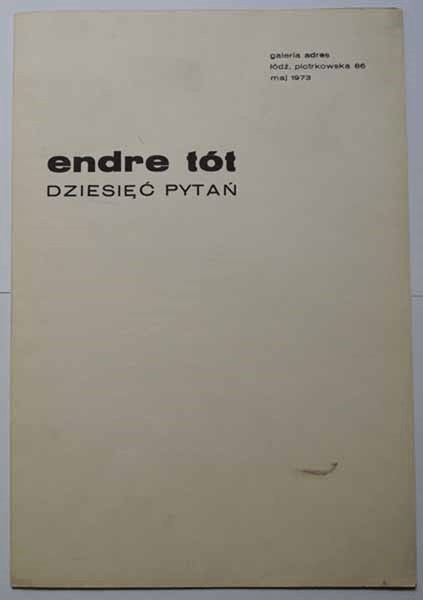

Partum explored the notion of the art gallery as an idea, or as a brand, publishing documentation and organizing exhibitions by the Galeria Adres outside of the apartment on Rybia Street, in public places related to international exchange. In 1973, she organized Endre Tót’s exhibition 10 Questions at the Continental Club, and in 1974, Maurice Roquet’s Entre Ensemble at the Press and Book Club, both in Łódź. The logo of the Galeria Adres, which appeared on all related print materials, was designed, published, and produced by Partum to be a mark that would connect particular objects and documents with the institution of Galeria Adres. In such a way, the change of context from ZPAP’s headquarters to Partum’s apartment did not affect the gallery’s artistic program, which continued to foster the neo-avant-garde art movement on local, regional, and transnational levels.

The Map of Transnational Networks

Although the gallery served multiple functions, it was nevertheless conceived primarily as a means to enable participation in the international art movement through the mail art network. Thus, the Galeria Adres was a working platform, enabling connections to Eastern European and Western artists working within a paradigm of ephemeral, conceptual, and/or process-based art. This dimension of Partum’s activity manifested itself in the form of a customized/amended world map, which hung on the wall in her apartment/Galeria Adres, and was used to record the circulation of materials, information, knowledges, and art documentation into and out of the space.

In her essay critiquing the superficiality of the internationalist discourse on conceptual art produced in its Western centers, Sophie Cras points out that maps have been misused as a means to “visualise false geographies”,31Sophie Cras, “Global Conceptualism? Cartographies of Conceptual Art in Pursuit of Decentering,” in Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann, Thomas, Catherine Dossin, and Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel, eds., Circulations in the Global History of Art (Farnham, Surrey, and Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2015), 168. and geographic ambitions.”32Ibid., 176. Cras suggests that claims of internationalism or decentering “only hid—or even justified—persisting geographical inequalities,”33Ibid. whereas “the maps were used at the time as visual statements, to either build or deconstruct this idea of international decentring through circulation.”34Ibid. In some cases, the author continues, maps clearly partake in the general discourse on internationalism in vogue at the time.

The Galeria Adres’s map functioned as both evidence of Partum’s geographic ambitions and proof of its internationalism, but it fulfilled a different function than the maps employed by the proponents of dematerialized art located in the Western centers. It visually constructed an aspirational, or false, geography, assigning the Galeria Adres to a place at the center of the art world, thereby serving the purpose—as defined by Piotrowski after Dipesh Chakrabarty—of provincializing the West.35Piotrowski in his postulate to provincialize Western art history, which is expressed in his writings (Piotr Piotrowksi, Awangarda w cieniu Jałty. Sztuka i polityka w Europie Środkowo-Wschodniej 1945-1989 (Poznań Rebis 2005) / English Edition: In the Shadow of Yalta: Art and the Avant-garde in Eastern Europe, 1945-1989(London, Reaktion Books 2009) refers to Dipesh Chakrabarty’s concept of provincializing Europe. See Dipesh Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference(Princeton, NJ, and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2000). It constituted a virtual network of art circulating from and to the Galeria Adres, and in that sense, it did not simply duplicate actual socioeconomic geography but instead re-inscribed relative artistic geography over it.

Partum’s networking efforts and the position of her gallery were recognized both locally and internationally as early as 1973. The gallery was invited to participate in the presentations of independent galleries in Poland that took place in Warsaw in 1973 and 1975 as well as to the International Festival of Students of Art Schools (F-ART) in Gdańsk in 1975, where Partum also presented her works and documentation from the Galeria Adres Archive, along with the visual poems by Richard Kostelanetz and Ken Friedman that were sent to her by the artists.

Also in 1973, Ken Friedman, a director of Fluxus West, who had an important role in initiating contacts with Eastern European artists, sent Partum a “Confidential International Contact List of the Arts,” which included more than 3000 addresses of artists, gallerists, and art collectors.36This was a confidential draft. The published version from 1972 is the one that circulated widely around the world. The title of the published version was International Contact List of the Arts. In the same year, Partum received a parcel with a selection of books from Dick Higgins’s Something Else Press.37Something Else Press books ran in editions ranging from 1,000 to 3,000 copies. These were circulating in Europe and the United States, spreading Fluxus ideas. Partum received the following books (the order follows the list attached to Higgins’s letter): Geoffrey Hendricks, Ring Piece (1973); Richard Kostelanetz, Breakthrough Fictioneers (1973); George Brecht and Robert Filliou, Games at the Cedilla, or the Cedilla Takes Off (1967); John Cage, Notations(1969); Alison Knowles, Tomas Schmit, Benjamin Patterson, and Philip Corner, The Four Suits(1965); Dick Higgins, A Book About Love and War and Death (1972); Dick Higgins, foew&ombwhnw(1969); Richard Huelsenbeck, DaDa Almanach(1966); Toby MacLennan, 1 Walked Out of 2 and Forgot It (1972); Bern Porter, I’ve Left (1971); Daniel Spoerri, An Anecdoted Topography of Chance (1966); Daniel Spoerri, The Mythological Travels of a Modern Sir John Mandeville, Being an Account of the Magic, Meatballs and Other Monkey Business Peculiar to the Sojourn of Daniel Spoerri on the Isle of Symi, Together with Divers Speculations Thereon (1970); Gertrude Stein, Matisse Picasso and Gertrude Stein (1972); Wolf Vostell and Dick Higgins, Fantastic Architecture (1970); Emmett Williams, An Anthology of Concrete Poetry (1967); John Cage, Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse); Manifestoes (Öyvind Fahlström, Robert Filliou, John Giorno, Al Hansen, Dick Higgins, Allan Kaprow, Alison Knowles, Nam June Paik, Diter Rot, Jerome Rothenberg, Wolf Vostell, Robert Watts, and Emmett Williams; 1966); and Diter Rot, A Look into a Blue Tide (1967). In other words, by 1973, the Galeria Adres had become one of the many points of contact for Fluxus artists (including Dick Higgins, Ben Vautier, and Eric Andersen) who had been working together with artists from Eastern Europe in Warsaw, Budapest, and Prague since mid-1960.38In Poland, intensive points of contact with Fluxus were, in the mid-1960s, the Zamek Group (Jerzy Ludwiński, Włodzimierz Borowski, Tytus Dzieduszycki, Jan Ziemski, and Ryszard Kiwerski); from 1966, Galeria Foksal, the Poetry Bureau (1971), and Galeria Akumulatory 2 (1972); and from the mid-1970s, also Galeria Piwna 20/26, Riviera-Remont in Warsaw, and Galeria Potocka in Krakow. The Galeria Adres participated in the initial stage of this exchange and communication between Polish neo-avant-garde and international Fluxus artists. Until the mid-1970s, the contact was merely occasional, and the first Fluxus Festival in Poland did not take place until 1977 in Jarosław Kozłowski’s Galeria Akumulatory 2 in Poznań.

To understand the specificity of the institutional strategy of the Galeria Adres with regards to international networks, it is interesting to compare Partum’s strategy with NET, a parallel initiative, or network, launched the same year (1972) by the artist Jarosław Kozłowski and theoretician Andrzej Kostołowski. Unlike the Galeria Adres, with its strong authorial presence and intensive publishing and archiving activities, NET was conceived as a decentralized network. Its authors deliberately resigned from the authorial license, stating in the founding manifesto that NET “ceases to be an authorized idea” and proposed that it can be copied and used in all possible ways by anybody who participates in the network.39The NET Manifesto (1972), signed by Jarosław Kozłowski and Andrzej Kostołowski reads: —NET is open and noncommercial —NET points are private homes, studios, and any premises in which the artistic proposals are articulated —these proposals are presented to the people who are interested in them —plans can be supported by editions in the form of press, slides, photographs, films, books, catalogues, flyers, letters, manuscripts, and the like —NET has no central point, nor any coordinates —NET points can be located anywhere —all NET points are in mutual contact and have concepts of exchange, proposals, projects, and other forms of circulation —the NET idea is not new and at this point ceases to be an authorized idea —NET can be arbitrarily developed and copied. NET functioned merely as a system of art circulation outside of art institutions; events related to the network took place in various private (apartment) and semiprivate (studio) venues. On the contrary, Galeria Adres was defined by Partum as part of her own private life. Its locale, the artist’s apartment, provided a framework for situating Partum’s activities at the center of this “infrastructure-in-the-making.” At the same time, the map created by Partum’s activities, and exhibited in the gallery, situated the Galeria Adres in the center of an international network. This double centering was opposite to NET’s idea of decentering. In other words, instead of reinventing the very concept of a network as Kozłowski and Kostołowski did, Partum articulated and negotiated her own position within the fragments of existing networks, devising the Galeria Adres as an apparatus of acceleration and expansion in particular directions.

Retrospectively, we can argue that the Galeria Adres became an apparatus of self-historization in the chosen transnational context. Through the activities of the gallery, Partum placed her practice within a fragment of the transnational network of the neo-avant-garde. This context was produced through the gallery’s publishing, production, and exhibition activities and has been preserved in the form of the Galeria Adres Archive.

- 1The Archive of the Galeria Adres has not been preserved in its entirety. My analysis is, therefore, based on a close examination of the remaining fragmentary material, which includes correspondence, mail art, books, catalogues, brochures, posters, experimental film scores, and notes. I also refer to art historical texts and especially to Dorota Monkiewicz’s essay published in 2015 (“On the International Artistic Exchange Network in Poland as Illustrated by the Example of Łódź’s Adres Gallery,” in Nothing Stops the Idea of Art, ed. Maria Morzuch, exh.cat. [Łódź: Muzeum Sztuki, 2015], 56–67), which constitutes the first attempt to historize the Galeria Adres’s activities. My knowledge of the gallery’s activities was also enriched by a series of interviews with Ewa Partum, Marek Żychski and other participants of the gallery activities, that I conducted during my doctoral dissertation’s research over the past 5 years.

- 2The notion of “art-infrastructure-in-the-making” was introduced by Irit Rogoff in a lecture delivered at the Former West Congress Documents, Constellations, Prospects, which took place March 18–24, 2013, at Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin. A recording of the lecture is available at http://www.formerwest.org/DocumentsConstellationsProspects/Contributions/Infrastructure.

- 3The Polish 1968 political crisis, known as “March 1968,” pertains to a series of protests against the Communist government that paralleled the Prague Spring. These protests were instrumentalized in orchestrating an anti-Semitic (branded anti-Zionist) campaign related to the power struggle within the Polish Communist Party. The anti-Jewish smear campaign, propaganda, mass mobilization, and continuous harassment resulted in the emigration of 13,000 citizens of Jewish descent.

- 4Edward Gierek remained in power for almost ten years, from December 20, 1970, to September 6, 1980.

- 5Piotr Piotrowski, Dekada: O Syndromie Lat Siedemdziesiątych, Kulturze Artystycznej, Krytyce, Sztuce-Wybiórczo i Subiektywnie(Poznań: Obserwator, 1991), 20.

- 6See, for example, the recently published comprehensive joint publication that frames neo-avant-garde art from Central-Eastern Europe within the concept of the second public sphere: Katalin Cseh-Varga and Adam Czirak, eds., Performance Art in the Second Public Sphere: Event-Based Art in Late Socialist Europe (New York: Routledge, 2018).

- 7Piotrowski also observed that apart from political reasons, the marginalization of neo-avant-garde art was related to pragmatic problems: a lack of strong (central) art institutions to promote neo-avant-garde values, as well as the mere incompetence of civil servants whose decisions were shaping the Polish cultural scene. See Piotrowski, Dekada, 20.

- 8Marcin Lachowski, Awangarda wobec instytucji. O sposobach prezentacji sztuki w PRL-u (Lublin: Towarzystwo Naukowe KUL 2006), 118–19.

- 9Jerzy Ludwiński, “Awangarda awangardy,” in Jarosław Kozłowski, (ed.): Sztuka w epoce postartystycznej i inne teksty (Akademia Sztuk Pięknych w Poznaniu, Biuro Wystaw Artystycznych we Wrocławiu, Poznan and Wroclaw 2009) 72-77, p.74. Ludwiński’s text was originally published in the journal Nadodrze no. 19 (1971).

- 10Rogoff, lecture delivered at Documents, Constellations, Prospects.

- 11Ibid.

- 12See, for example, Jarosław Jakimczyk, Najweselszy Barak w Obozie: Tajna policja komunistyczna jako krytyk artystyczny i kurator sztuki w PRL-u (Warsaw: Akces 2015).

- 13Considering the spatio-temporal significance of the local, Elspeth Probyn distinguishes between “locale” and “location,” defining “locale” as a place that is the setting for a particular event: “A place understood as both a discursive and non-discursive arrangement that holds an even.” See locale Elspeth Probyn, “Travels in Postmodern: Making Sense of the Local,” in: Linda J. Nicholson, (ed.): Feminism/Postmodernism (New York and London, Routledge 1990), 76-189, p.178.

- 14Rogoff, lecture delivered at Documents, Constellations, Prospects.

- 15In A Thousand Plateaus, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari list a series of characteristics of the rhizome as the principles of connection and heterogeneity, multiplicity, assignifying rupture, cartography, and decalcomania. The principle of assignifying rupture means that “a rhizome may be broken, shattered at a given spot, but will start up again, on one of its old lines, or on new lines.” Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, 2nd ed. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 303.

- 16At the beginning of the 1970s, Łódź had become a place where conceptual activities could be realized within the framework of art galleries. In May 1971, the conceptual art gallery 80 x 140 was founded there, initiated by Jerzy Treliński with a flash card indicating the space’s measurements. The gallery’s activities took place inside the ZPAP building, as well as outside of it. From May 1972, the gallery coexisted with the gallery A4—namely a piece of paper in the A4 format with the name of the gallery inscribed on it by Andrzej Pierzgalski.

- 17The original text reads, “Pole działania artystycznego / Zamiast reprezentacji i reprezentowania / (wzajemnej adoracji siebie samych) / wymaga działania artystycznego w szerszym sensie” (1972). “A Filed of Artistic Action/ Instead of Representation and Representing (a Mutual Adoration) / Demands an Artistic Action in a Broader Sense.”

- 18At the beginning of the 1970s in Poland, French was still considered an international language, but in 1972, Ewa Partum began using English in the titles of her works and publications. Partum’s texts were originally written in Polish and translated by her collaborators Marek Żychski (English translator), Kader Lactta and Rolland Paret (international students from the Łódź Film Academy), and Ewa Zając (Partum’s friend and collaborator.)

- 19In 1971, Partum published a gallery manifesto that was republished in 1972 in Notatnik Robotnika Sztuki/Art’s Worker Notebook, an art zine published by Galeria ELin Elbląg.

- 20Ewa Partum, Galeria Adres Documentation (Łódź: TVP, 1971–72), 3 min. 36 sec., 8 mm, http://post.at.moma.org/sources/30/publications/287?_ga=2.134658353.1596660259.1523983044-774675610.1512302028.

- 21Klaus Groh’s influential publication (Klaus Groh, Aktuelle Kunst in Osteuropa: CSSR, Jugoslawien, Polen, Rumänien, UdSSR, Ungarn [Cologne: DuMont, 1972]), did not include Ewa Partum’s practice.

- 22Monkiewicz, “On the International Artistic Exchange Network in Poland as Illustrated by the Example of Łódź’s Adres Gallery,” 61.

- 23Jean Baudrillard, “Beyond the Vanishing Point of Art” (1988), quoted in Alexander Alberro, Conceptual Art and the Politics of Publicity(Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003), 150.

- 24Sjoerd van Tuinen and Stephen Zepke, introduction to Art History after Deleuze and Guattari, eds. Sjoerd van Tuinen and Stephen Zepke (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2017), 17.

- 25In the Galeria Adres Archive, there is a letter of support that was initiated by Partum and signed by many culture producers, including art historians and artists related to the neo-avant-garde art movement such as Józef Robakowski, Wojciech Bruszewski, Paweł Kwiek, and Ryszard Waśko.

- 26Piotrowski, Dekada, 20.

- 27“Moja galeria jest domem”/ “My Gallery is a Home,” a handwritten and undated note in the Ewa Partum Archive.

- 28A discourse on the privacy of aesthetic experience was introduced into Polish conceptual art practices later on, in exhibitions such as Private Views (1978) or Individual Mythologies (1980), in which art is defined as a sphere of privacy in accordance with the individual character of aesthetic experience. See Luiza Nader, Konceptualizm w PRL, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego and Fundacja Galerii Foksal, Warszawa, 2009, 182.

- 29Piotr Piotrowski, Znaczenia modernizmu: W stronę historii sztuki Polskiej po 1945, 2nd ed. (Poznań: Dom Wydawniczy Rebis, 2011), 211.

- 30Galeria Adres translates as “Address’ Gallery.”

- 31Sophie Cras, “Global Conceptualism? Cartographies of Conceptual Art in Pursuit of Decentering,” in Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann, Thomas, Catherine Dossin, and Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel, eds., Circulations in the Global History of Art (Farnham, Surrey, and Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2015), 168.

- 32Ibid., 176.

- 33Ibid.

- 34Ibid.

- 35Piotrowski in his postulate to provincialize Western art history, which is expressed in his writings (Piotr Piotrowksi, Awangarda w cieniu Jałty. Sztuka i polityka w Europie Środkowo-Wschodniej 1945-1989 (Poznań Rebis 2005) / English Edition: In the Shadow of Yalta: Art and the Avant-garde in Eastern Europe, 1945-1989(London, Reaktion Books 2009) refers to Dipesh Chakrabarty’s concept of provincializing Europe. See Dipesh Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference(Princeton, NJ, and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2000).

- 36This was a confidential draft. The published version from 1972 is the one that circulated widely around the world. The title of the published version was International Contact List of the Arts.

- 37Something Else Press books ran in editions ranging from 1,000 to 3,000 copies. These were circulating in Europe and the United States, spreading Fluxus ideas. Partum received the following books (the order follows the list attached to Higgins’s letter): Geoffrey Hendricks, Ring Piece (1973); Richard Kostelanetz, Breakthrough Fictioneers (1973); George Brecht and Robert Filliou, Games at the Cedilla, or the Cedilla Takes Off (1967); John Cage, Notations(1969); Alison Knowles, Tomas Schmit, Benjamin Patterson, and Philip Corner, The Four Suits(1965); Dick Higgins, A Book About Love and War and Death (1972); Dick Higgins, foew&ombwhnw(1969); Richard Huelsenbeck, DaDa Almanach(1966); Toby MacLennan, 1 Walked Out of 2 and Forgot It (1972); Bern Porter, I’ve Left (1971); Daniel Spoerri, An Anecdoted Topography of Chance (1966); Daniel Spoerri, The Mythological Travels of a Modern Sir John Mandeville, Being an Account of the Magic, Meatballs and Other Monkey Business Peculiar to the Sojourn of Daniel Spoerri on the Isle of Symi, Together with Divers Speculations Thereon (1970); Gertrude Stein, Matisse Picasso and Gertrude Stein (1972); Wolf Vostell and Dick Higgins, Fantastic Architecture (1970); Emmett Williams, An Anthology of Concrete Poetry (1967); John Cage, Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse); Manifestoes (Öyvind Fahlström, Robert Filliou, John Giorno, Al Hansen, Dick Higgins, Allan Kaprow, Alison Knowles, Nam June Paik, Diter Rot, Jerome Rothenberg, Wolf Vostell, Robert Watts, and Emmett Williams; 1966); and Diter Rot, A Look into a Blue Tide (1967).

- 38In Poland, intensive points of contact with Fluxus were, in the mid-1960s, the Zamek Group (Jerzy Ludwiński, Włodzimierz Borowski, Tytus Dzieduszycki, Jan Ziemski, and Ryszard Kiwerski); from 1966, Galeria Foksal, the Poetry Bureau (1971), and Galeria Akumulatory 2 (1972); and from the mid-1970s, also Galeria Piwna 20/26, Riviera-Remont in Warsaw, and Galeria Potocka in Krakow.

- 39The NET Manifesto (1972), signed by Jarosław Kozłowski and Andrzej Kostołowski reads: —NET is open and noncommercial —NET points are private homes, studios, and any premises in which the artistic proposals are articulated —these proposals are presented to the people who are interested in them —plans can be supported by editions in the form of press, slides, photographs, films, books, catalogues, flyers, letters, manuscripts, and the like —NET has no central point, nor any coordinates —NET points can be located anywhere —all NET points are in mutual contact and have concepts of exchange, proposals, projects, and other forms of circulation —the NET idea is not new and at this point ceases to be an authorized idea —NET can be arbitrarily developed and copied.