Since the 1990s, Jean Depara has become famous for his portraits of brash city dwellers, and for his hedonistic depictions of their unbridled nightlife. This essay explores how Depara’s transgressive photographs emerged in the interstices of the otherwise very controlled Belgian colonial “image world.” Sandrine Colard argues that the 1960 threshold of independence in these photographs becomes nearly imperceptible because Depara’s 1950s images literally prefigure, in the sense of “presenting before their time,” a vision of independence. Depara’s images remained misconstrued or invisible to the colonizer — an elusion that foreshadowed the realization of political autonomy.

On a summer day in 2013, I was warmly received by the Belgian photographer Henri Goldstein in his Brussels apartment for what he announced would be his last interview. Fifty-three years earlier, he had reluctantly left the Congo and his position as the head of the photography department of the colonial information service when the colony unexpectedly gained its independence. Between 1947 and 1960, Goldstein had been given a wealth of means to survey the Congolese cities, landscapes, and “traditions and progress” with his camera, and he was one of the main authors of the photographic propaganda of the postwar Belgian Congo. Now he was a very old and ailing man, and his memory was inexhaustible as he recaptured what he described as the most beautiful thirteen years of his life. Toward the end of our conversation, however, my last question left Goldstein at a loss for words. Presenting him with some pictures by the Congolese Jean Depara, I asked if he had ever had the chance to meet this fellow photographer in the 1950s, when they both resided in Léopoldville, the colony’s capital. Since the 1990s, Depara has become famous for his portraits of brash city dwellers, and for his hedonistic depictions of their unbridled nightlife. Discovering Depara’s name and images for the first time, Goldstein remained visibly perplexed, if not disoriented, and he assured me that none of these photographs could have been taken in the Belgian Congo, or even in the wake of its independence. The interview ended on this unresolved note, and Goldstein passed away a few months later, convinced that Depara and his subjects had never been his own contemporaries in Léopoldville.

This essay explores how the transgressive photographs of Jean Depara, whose career spanned from 1951 to 1975, emerged in the interstices of the otherwise very controlled Belgian colonial “image world.”1Deborah Poole, Vision, Race and Modernity: A Visual Economy of the Andean Image World (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997). His parallel visual economy was paradoxically made possible by the space and time segregation enforced in the city of Léopoldville, as it allowed alternative Congolese subjectivities to thrive shielded from the colonial gaze. The periodization of Depara’s photographs is rarely specifically detailed, with his images usually simply marked “ca. 1950–1970.” This essay argues that the 1960 threshold of independence is almost imperceptible because Depara’s 1950s images literally prefigure, in the sense of “presenting before their time,” a vision of independence. It further argues that similarly to other forms of Congolese resistance, Depara’s images remained misconstrued or invisible to the colonizer — just as they were to Goldstein’s eyes — and that this elusion foreshadowed the realization of political autonomy.

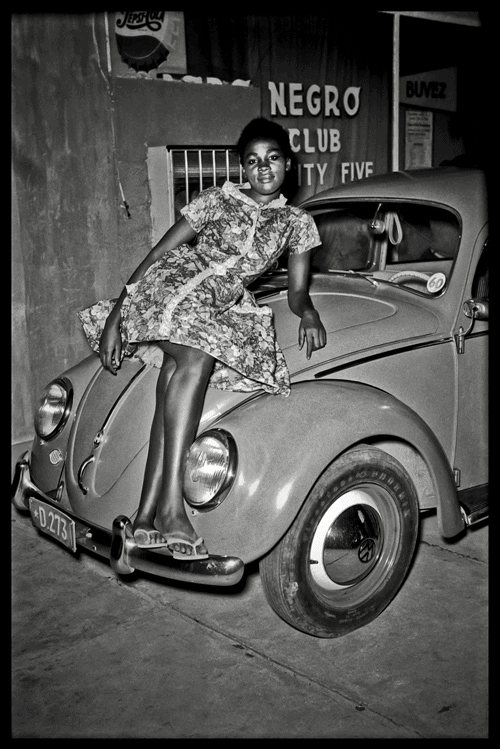

Born in neighboring Angola, Jean Depara (1928–1997) arrived in the vibrant city of Léopoldville in 1951. After having tried his hand at a series of small jobs, the purchase of an Adox 6×6 camera to document his wedding inspired a passion for image making, and that same year, he opened his own photography business. The stamp on the backs of his early prints reads as a cryptic anticolonial manifesto, one infused with the cockiness for which the city’s inhabitants are famous. The top line, “PHOTO CONTRE MAÎTRE,” is the name of the first iteration of Depara’s business, but above all it is a subversive double entendre: “Contremaître” designates a foreman in French, and thus this self-appointed title is Depara’s tongue-in-cheek advertisement of his photographic skills, which he suggests, are superior to those of his peers, mere subcontractors. The architectural lexicon floated in the air of the booming 1950s Léopoldville, at a time when investments in the Congo’s urban planning created such a building frenzy that the entire country looked like a “construction site.” Newly built wide boulevards and skyscrapers gave “Léo” such an American look that it was celebrated as even more modern than Brussels itself, the metropole’s capital. However, laid out as separate words, i.e., “contre” and “maître,” the term translates as “against the master”—and it takes little imagination to understand which oppressive master needed to be opposed in the decade that led up to African independences.

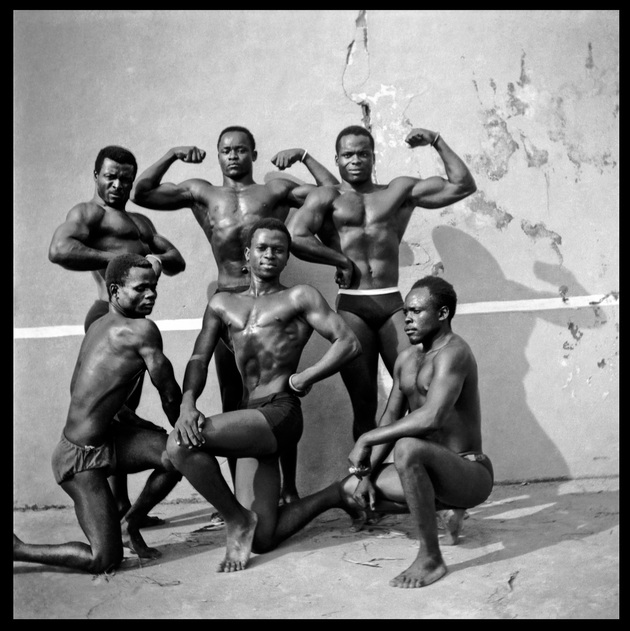

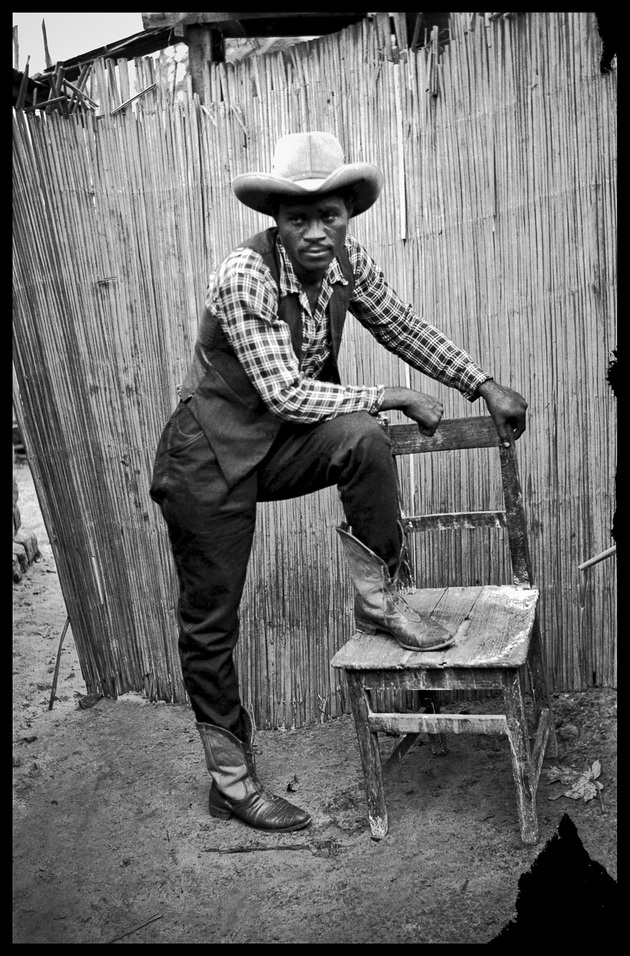

As benign as the other lines read at first sight, they were similarly anarchist blows leveled at the respectable model of the middle-class “évolué”2The “évolué,” or literally “evolved,” was the racist and condescending term given to the educated and Europeanized small bourgeoisie that started to emerge before World War II. inhabiting the social promised land painted by the colonial administration for all Congolese.3On the eve of World War II, the Belgian colonial administration put in place an information propaganda agency that included a prolific photographic service. In its last iteration, known as InforCongo, the team of photographers supervised by Henri Goldstein were invested with the mission of comprehensively — and positively — representing the colony for the world. Organized in a rigorous system of classification that was mostly free of copyright, more than twenty thousand images enjoyed worldwide circulation that guaranteed the quasi monopole control over the imaging of the Belgian Congo. “L’argent qui m’embête,” or “the money that irks me,” scoffed at the bourgeois ideal of the male financial purveyor, but it also flouted the laws that regulated Africans’ entrance into the city. Even if regularly bypassed, permissions for legal stays in Léopoldville were granted only upon proof of employment and accompanying salary.4Emmanuel Capelle, La Cité indigène de Léopoldville (Léopoldville: Centre d’études sociales africaines [CESA]; Elisabethville: Centre d’Etude des problèmes sociaux indigènes [CEPSI] in association with Des Presses Imbelco, 1947). In lieu of law-abiding “évolués” — usually educated clerks or small entrepreneurs serving the economy and administration of the colony — the subjects that Depara’s portraits celebrate are the rumba musicians and their subversive lyrics, muscle-flexing and parading body builders, and the eccentric “Bills,” the societies of dropouts converted to a life of more or less petty crime, and whose inspiration was the American cowboy Buffalo Bill. These radically diverging performances of masculinities cohabited in the cité indigene (indigenous quarters) with, on one end of the spectrum, the family-man “évolué” emulating the model of bourgeois domesticity and respectability, and on the other end, the pretendedly armed, nonchalant, single but womanizing “gangster,” who fears neither the Christian god nor the colonial man.

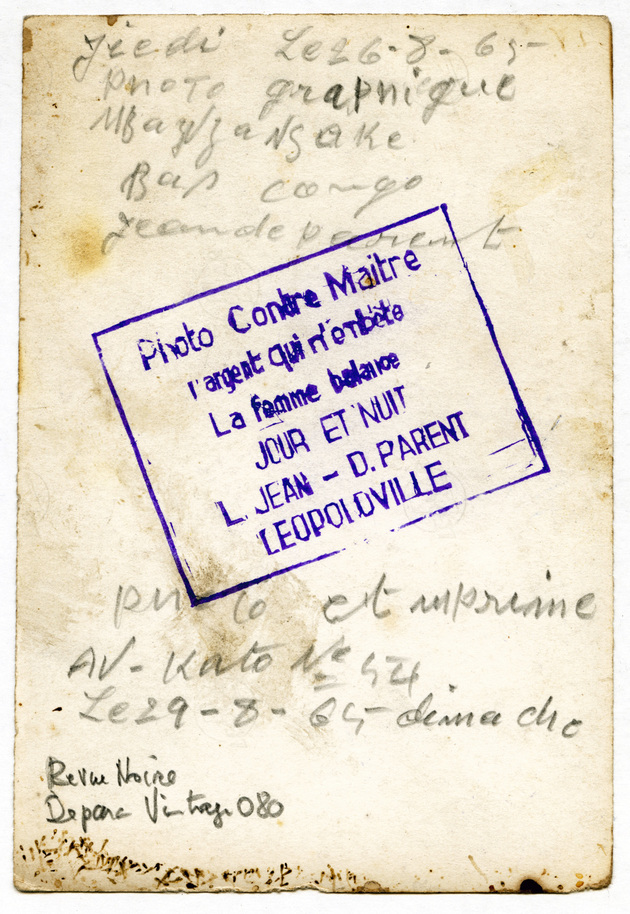

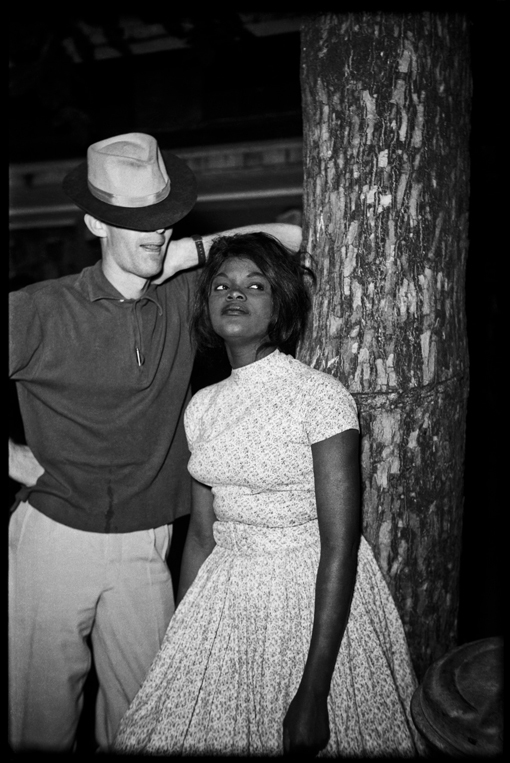

The next line of Depara’s stamp—“La femme balance,” or “the woman swings,” was a yearning nod to the hip-swaying “free women” who populated the cité and Depara’s pictures. The antithesis of the unassuming mother and ménagère (housewife) of the colonial picture, Depara’s ladies posed in such liberated ways that, more than thirty years later, the photographer was still vetoing the public disclosure of some of these risqué images out of consideration for the reputations of his audacious models.5Pascal Martin Saint Léon and Jean-Loup Pivin, “Kinshasa, Night and Day, 1951–1975,” in Jean Depara, PhotoBolsillo, Biblioteca de fotógrafos africanos (Madrid: La Fábrica, 2010). The alleged deplorable morality of many of the cité’s women was a recurrent lament of Belgian colonial literature.6Capelle, La Cité indigène de Léopoldville, 59. Mostly, they were vilified for being freely in charge of their own sexuality — whether they made commerce out of it or not. Undeniably the victims of a layered patriarchy — colonial, Christian, and that of the largely male majority of the cité7In 1947, the Léopoldville cité counted 44,639 men; 26,494 women and 29,457 children. Ibid., 29. — Depara’s female subjects nevertheless made an uninhibited spectacle of their sensuality — in private bedrooms or in public bars — that repudiated all of the models with which they were presented. Not infrequently coiled in the arms of white gentlemen, they simultaneously breached the color bar that divided Léopolville’s inhabitants.

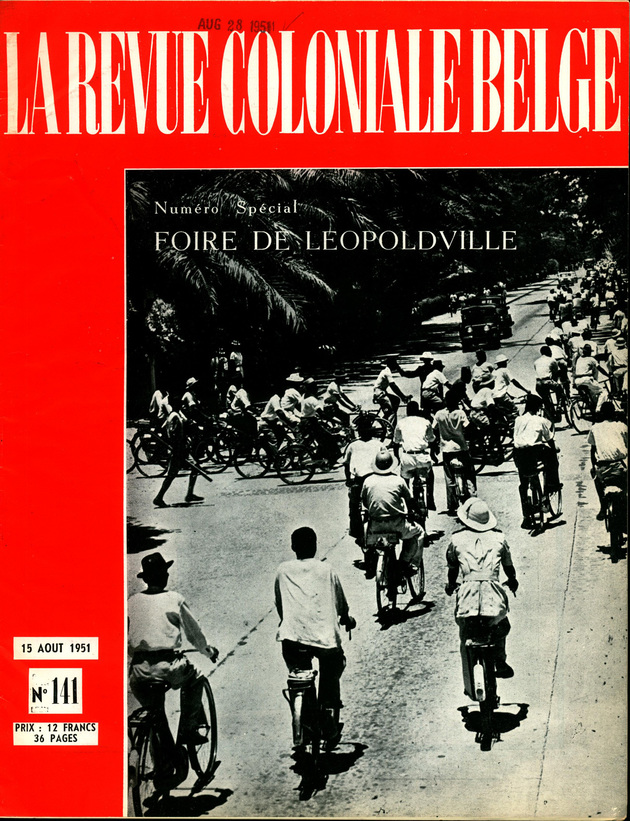

Finally, “JOUR ET NUIT,” or the “day and night” line advertising Depara’s twenty-four-hour service, was certainly not the least of his transgressions, in a colony where the management of Africans’ time was a central tool of control. Even before independence, a vast number of Depara’s photographs were taken at night, during the dusk-to-dawn curfew that forced the retreat of Congolese into their designated residential area. An official and many times reproduced image made by one of Goldstein’s colleagues suggests pride in the disciplined ranks of “natives” pedaling back to the cité indigène at the sound of the siren signaling the end of their workday.

Separated from the European city by a “neutral zone” of 400 meters, the indigenous quarter was the operational field of Depara. The multitude of “nganda” (bars) and dance halls that served as the night owl photographer’s favorite décors — OK Bar, Kongo Bar, Opika Bar, Binga Bar, etc. — were officially closed at 9:30 p.m.8Cappelle, La Cité indigène de Léopoldville, 73. Past this limit, as Ch. Didier Gondola describes in his book Tropical Cowboys, the restless inhabitants of the cité were lulled to the sound of a menacing tune: “Holding hurricane lamps and armed with sticks or chicotes, Force Publique agents routinely patrolled the streets shouting ‘Tolala! Tolala!’ (Go to sleep! Go to sleep!), a tocsin of apathy that echoed in all sections of the ghostly townships, a sort of hypnotizing incantation intended to rock the natives into quiescence and political inertia. This was also a crude way to infantilize African men, to sear and saturate their sensory experience of colonization with sounds, images, smells, and tastes of domination.”9Ch. Didier Gondola, Tropical Cowboys: Westerns, Violence, and Masculinity in Kinshasa (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2016), 42. The chicotte was a whip made of twisted hippopotamus skin and known for the particularly vicious pain it inflicted. Its use throughout the time of the Belgian colonial period has made it a symbol of colonial violence. The Force Publique was the indigenous army. These successive injunctions to recede — behind the neutral zone and into somnolence — had the main purpose of preventing disorder and subversive behaviors, all of which are nevertheless sprawled out in Depara’s photographs.

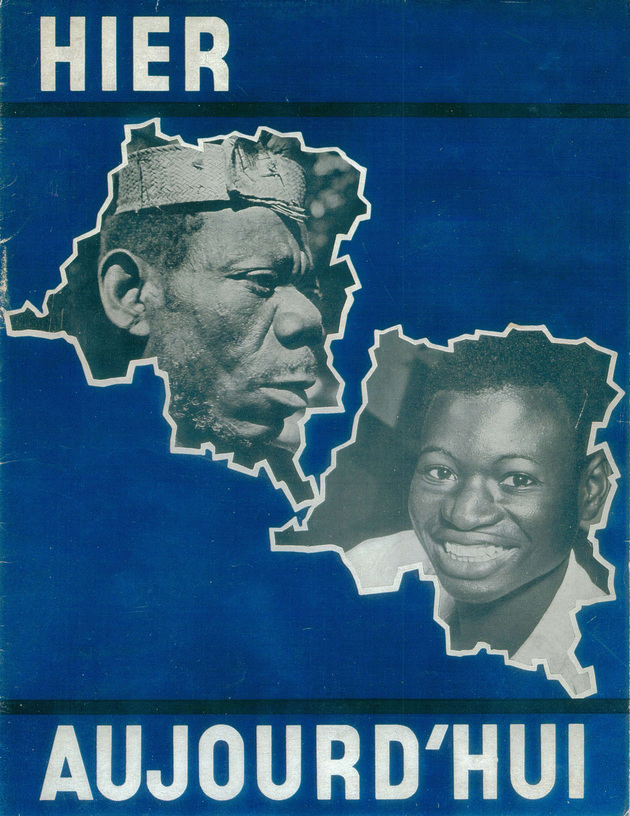

The Congolese subjectivities in Depara’s pictures deviate from the trajectory traced by the Belgian authorities toward the civilizational telos, and repeatedly represented as a timeline. One of the propaganda posters circulated at the end of the 1950s could not have made that clearer. Placed on a blue background in Congo-shaped frames, the portraits of a traditional-looking, older African belong to “hier” (yesterday), while the young, smiling “civilized” boy embodies “aujourd’hui” (today), or the present. The future that lay ahead was kept out of view and reach, as an indefinite curfew imposed on the aspirations of the Congolese. However, by literally and figuratively “staying awake,” Depara and his subjects made these turbulent nights Trojan horses in a decolonized temporal order, where a vision of independence could be developed. At its core, the struggle for independence was a battle about time, or as Dipesh Chakrabarty wrote in his influential book Provincializing Europe, “somebody’s way of saying ‘not yet’ to somebody else,”10Dipesh Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2000), 8. of keeping them in the waiting room of history. This was not lost on the rumba musicians who Depara spent so much time photographing. In 1955, the famous song “Ata Ndele (Mokili Ekobaluka),” or “Sooner or Later (The World Will Change),” was released, and it resonated as an unofficial anthem to the ears of Depara and his clientele. Blind to the images of the cité, the Belgians, just like Goldstein, missed the signs of a future’s rising much sooner than was expected.

- 1Deborah Poole, Vision, Race and Modernity: A Visual Economy of the Andean Image World (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997).

- 2The “évolué,” or literally “evolved,” was the racist and condescending term given to the educated and Europeanized small bourgeoisie that started to emerge before World War II.

- 3On the eve of World War II, the Belgian colonial administration put in place an information propaganda agency that included a prolific photographic service. In its last iteration, known as InforCongo, the team of photographers supervised by Henri Goldstein were invested with the mission of comprehensively — and positively — representing the colony for the world. Organized in a rigorous system of classification that was mostly free of copyright, more than twenty thousand images enjoyed worldwide circulation that guaranteed the quasi monopole control over the imaging of the Belgian Congo.

- 4Emmanuel Capelle, La Cité indigène de Léopoldville (Léopoldville: Centre d’études sociales africaines [CESA]; Elisabethville: Centre d’Etude des problèmes sociaux indigènes [CEPSI] in association with Des Presses Imbelco, 1947).

- 5Pascal Martin Saint Léon and Jean-Loup Pivin, “Kinshasa, Night and Day, 1951–1975,” in Jean Depara, PhotoBolsillo, Biblioteca de fotógrafos africanos (Madrid: La Fábrica, 2010).

- 6Capelle, La Cité indigène de Léopoldville, 59.

- 7In 1947, the Léopoldville cité counted 44,639 men; 26,494 women and 29,457 children. Ibid., 29.

- 8Cappelle, La Cité indigène de Léopoldville, 73.

- 9Ch. Didier Gondola, Tropical Cowboys: Westerns, Violence, and Masculinity in Kinshasa (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2016), 42. The chicotte was a whip made of twisted hippopotamus skin and known for the particularly vicious pain it inflicted. Its use throughout the time of the Belgian colonial period has made it a symbol of colonial violence. The Force Publique was the indigenous army.

- 10Dipesh Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2000), 8.