Mulk Raj Anand is perhaps best remembered as a cultural critic, writer, philosopher, and patron of the arts. But Rashmi Viswanathan turns her attention to his lesser known initiative to establish India’s First Triennale of Contemporary World Art in 1968. This essay explores Anand’s optimistic use of the triennale to shift international cultural relations and make a claim for cultural self-determination. Anand’s engagement with the arts should be understood within his broader project of imagining a progressive secular state, as India negotiated the terms of its unfolding nationhood and modernity.

Mulk Raj Anand (1905–2004), the founder of Marg magazine (since 1946), one of India’s oldest publications dedicated to the visual and performing arts, is perhaps best remembered as a cultural critic, writer, philosopher, and patron of the arts. Less well-known is his initiative to establish India’s First Triennale of Contemporary World Art in 1968, the country’s first contribution to a now-common global art-exhibition format. Left in relative obscurity as a result of its failure to generate regular successive editions, this ill-fated exhibition nonetheless casts light on the efforts to reorient India’s position in the modern art world, as a newly decolonized country and in the Cold war era.1Ranjit Hoskote connects the impoverished momentum of the triennale to the loss of its original political drive, which resulted in institutional desiccation: “The India Triennial is an instance of a biennial lapsing into neglect and oblivion as a result of the loss of its original propulsive ideological fervor and the political commitment of its organizers, followed by a bureaucratization of culture, which causes the fossilization of an inspiring idea into a set of routine commissioning procedures traced over diplomatic treaties of cultural exchange between the host nation-state and other nation-states.” Ranjit Hoskote, “Biennials of Resistance: Reflections on the Seventh Gwangju Biennial,” in The Biennial Reader, eds. Elena Filipovic, Marieke van Hal, Solveig Øvstebø (Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Kantz, 2010), 310.

Anand was born in 1905 in Peshawar, in what is now Pakistan, and in 1925, he moved to London, partly as the result of a self-imposed exile following his arrest for anti-British agitation in India. He enrolled at University College London in 1929, earning a doctorate in philosophy under the supervision of the Kantian scholar Dawes Hicks. His earliest associations in England sparked interest in the young writer in a brand of egalitarianism. He sympathized with the general strike of 1926, a broadscale worker-led protest against labor conditions in the coal-mining industry. He found like-minded intellectuals while working as a reviewer for T. S. Eliot at Criterion, a literary magazine, and for Leonard Woolf with Hogarth Press and associating with the Bloomsbury Group. Bound by shared political sympathies, the left-leaning group shared an aesthetic commitment to a socialist internationalism that was sensitive to the commercial and political tethering of India to Great Britain and vice versa. In 1928, he briefly returned to India, where he met Jawaharlal Nehru (India’s future first prime minister), whose politics of international solidarity and belief in progress through secular state interventionism in the cultural sector would also impact Anand. In 1932, he initiated a fulfilling friendship with the Indian advocate for independence Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, who inflected Anand’s turn toward a more political commitment to social reform. Holding architecture and art as potent liberating forces, Anand saw their instrumentality in British India’s claims to nationhood.

At stake for Anand was the articulation of an identity for the incipient nation through material cultural expression—art and architecture for a country that was “situated between two worlds, one not yet dead, the other refusing to be born.”2Mulk Raj Anand, “The Monkey Business or a New Experimental Architecture in India,” typed draft manuscript, undated, cited in Mustansir Dalvi, “Mulk and Modern Indian Architecture,” in Mulk Raj Anand: Shaping the Indian Modern, ed. Annapurna Garimella, Marg (Monograph series; Mumbai: Marg Publications, 2005), 56–57. Anand neither romanticized an imagined pristine Indian past nor shunned the emancipatory project of the European Enlightenment. Rather, within the crucible of modern state formation, art, in his estimation, had the unique capacity to express local sociologies of knowledge and universalist aspirations. His model of Indian-European philosophical synthesis in his advocacy of a modern India evolved over time as India’s position shifted on the Cold War geopolitical stage, following its independence from British rule in 1947.3See Geeta Kapur, “Partisan Modernity,” in ibid., 28–42. See also Jessica Berman, “Toward a Regional Cosmopolitanism: The Case of Mulk Raj Anand,” MFS Modern Fiction Studies 55, no. 1 (Spring 2009): 142–62.

By the 1950s, the momentum of the decolonization movements had sharply accelerated. The Bandung Conference of 1955 saw a number of Asian and African nations meet in the spirit of economic and social cooperation as well as allied opposition to colonial rule. Formalized in the Non-Alignment Movement of 1961 under Gamal Abdel Nasser (Egypt), Kwame Nkrumah (Ghana), Sukarno (Indonesia), Jawaharlal Nehru (India), and Josip Broz Tito (Yugoslavia), the initiative formally distanced member countries from the postwar geopolitical tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union. In 1958, the Afro-Asian Peoples Solidarity Organization, a non-governmental pluralist and democratic organization, was established at an inaugural conference held in Cairo. Perhaps more importantly, the organization, of which Anand was a vocal advocate, endured considerable infighting in the mid-1960s. Continually shifting alliances in the newly formed coalitions placed India in a rather precarious position vis–à–vis the Soviet Union, whose support (unexpectedly) became politically expedient by the late 1960s. In a landscape of shifting alliances, Anand may have viewed the triennale as a strategy for articulating new cultural affinities and as an independent act of self-determination—of “cultural self-comprehension” for the newly independent and uncertain India.4Mulk Raj Anand, “The Search for National Identity in India,” in Cultural Self-Comprehension of Nations, ed. Hans Köchler (Tübingen/Basel: Horst Erdmannn Verlag, 1978), 73–97.

The First Triennale of Contemporary World Art (February–March 1968)

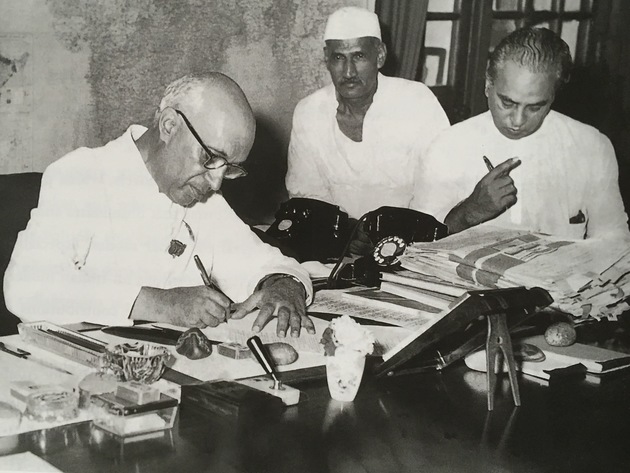

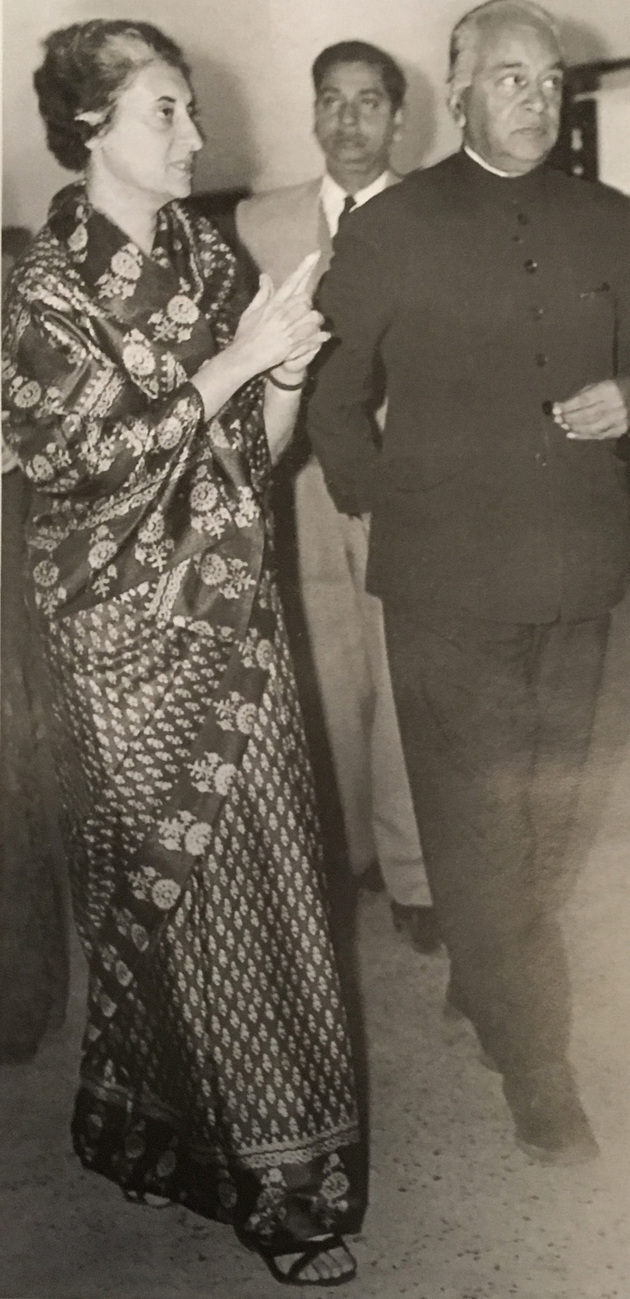

With the support of the Indian government, Anand, then chairman of the Lalit Kala Akademi (National Academy of Art), initiated India’s First Triennale of Contemporary World Art in 1968. In his preface to the catalogue, he makes explicit the exhibition’s emulation of the Venice, Sao Paolo, Tokyo, and Paris biennials, and his envisioning of it as a key shift in “international cultural relations” for India.5Mulk Raj Anand, The First Triennale of Contemporary World Art (New Delhi: Lalit Kala Akademi, 1968), 5. Its international jury reviewed works from thirty-one countries, the final selection from which was displayed in national pavilions. The exhibit featured more than six hundred works in two New Delhi venues: the Lalit Kala Gallery and the National Gallery of Modern Art at Jaipur House.6The jury consisted of Anand; the poet and art critic Octavio Paz; Nasayoshi Homma, Curator in Chief, the Museum of Modern Art (Tokyo); Norman Reid, Director, Tate Gallery; Prithwish Neogy, Professor of Fine Arts, University of Hawaii; Dr. A. F. Jakimowicz of the International Association of Art Critics; and R. Von Leyden, contributing editor to Marg, art critic, and connoisseur. In addition, Anand mounted published a corollary pictorial exhibition of sorts for in the journal Marg (1968), which included a catalogue of sculpture organized by nation.7This was intended to offset the lack of large-scale plastic arts, which were prohibitively expensive and difficult to ship.

The global format of the triennale offered an aspirational space for the redrawing of national interrelationships and the production of new community networks. The catalogue entries for the triennale are preceded by a set of notes from well-wishers, including Henry Moore; the English anarchist and art historian Herbert Read; Joan Miro; George Keyt; the English artist and historian Roland Penrose; the English art critic, novelist, painter, and poet John Berger; the office of the Director-General of UNESCO, and Alfred H. Barr Jr. Fierily invoking the utopian communality of the project, Berger wrote:

“I send my greetings to the first Triennale of Contemporary World Art to be held in India. It would suggest the possibility of escaping from or even overthrowing the hegemony of Europe and North America in these matters. This hegemony is disastrous because, whatever the personal feelings or ideas of individual artists or teachers may be, it is based upon the concept of a visual work of art as property. The historical usefulness of such a concept has long past: it stands now as a barrier to further development. The ideology of modern European property is inseparable from imperialism. The fight against imperialism and all its agencies is thus closely connected with the struggle for a truly modern art. I wish you clear-sightedness, strength and courage in your struggle.”8John Berger in a letter dated January 10, 1968 among a number of letters reproduced in Anand, preface to The First Triennale of Contemporary World Art.

Aligning a new modernity in the arts with a political trajectory, Berger echoed Anand’s disdain for what he viewed as the art market’s empty promises of individuality and self-expression. The triennale, in a sense, provided a platform for the re-inscription of values in and of art, which drew from the force of individual expression to symbolically validate new cultural affinities and invalidate existing cultural and political hegemonies.

The Global Stage

Anand’s engagement with the arts extended beyond his support of contemporary practice, and should be understood within his broader project of giving historical context to India as it negotiated the terms of its unfolding nationhood and modernity. In line with Nehruvian thought, Anand looked both backward to pre-colonial Indian art to give historical heft to the forming nation, and forward, to an unfolding rational humanist state. Consequently, he articulated national-cultural identity within a larger supranational frame.9Besides his triennale undertaking, Anand wrote a series of art histories, including_ Persian Painting (1930), The Hindu View of Art (1933), and the controversial Kama-Kala: Some Notes on the Philosophical Basis of Hindu Erotic Sculpture_ (1958). Keenly aware of the global field in which the proposed political restructuring of the non-alignment took place, Anand may well have viewed New Delhi, the site of the triennale, as reflective of the importance of the Indian state to the progress of the cultural sector. The triennaleformat—global with discrete national pavilions—provided an exemplary space for the reconfiguration of the art world. Moreover, its lack of precedent in the Indian context permitted it to function as an experimental theater of sorts—as a forward-looking endeavor. It made it a thing of possibility; capacious; the product, reflection, and demonstration of collective efforts, one in which India could physically take its place alongside American and Soviet cultural production. And Anand was keen on the potential of experiment as progressive practice, and modernist art as a revolutionary tool: “Even a cursory look at the contributions from the various countries, will confirm the impression that the large majority of the artists of the world have gone on to an experimentalism which was, perhaps, implicit in the force released by the machine civilization of the world.”10Anand, preface to The First Triennale of Contemporary World Art.

“The prophet Tolstoy called it (art) an ‘instrument of peace’. I suggest that art is the most important weapon of creative humanism—the only ism left in the world in which we might believe.”11Ibid., 8.

Nancy Adajania explores Anand’s establishment of the triennale in light of decolonization movements and the Non-Alignment Movement in “Globalism Before Globalisation: The Ambivalent Fate of Triennale India,” in Western Artists and India: Creative Inspirations in Art and Design, ed. Shanay Jhaveri. (London: Thames and Hudson, 2013), 168–85, http://www.academia.edu/7818709/Nancy_Adajania_Globalism_Before_Globalisation_The_Ambivalent_Fate_of_Triennale_India.

- 1Ranjit Hoskote connects the impoverished momentum of the triennale to the loss of its original political drive, which resulted in institutional desiccation: “The India Triennial is an instance of a biennial lapsing into neglect and oblivion as a result of the loss of its original propulsive ideological fervor and the political commitment of its organizers, followed by a bureaucratization of culture, which causes the fossilization of an inspiring idea into a set of routine commissioning procedures traced over diplomatic treaties of cultural exchange between the host nation-state and other nation-states.” Ranjit Hoskote, “Biennials of Resistance: Reflections on the Seventh Gwangju Biennial,” in The Biennial Reader, eds. Elena Filipovic, Marieke van Hal, Solveig Øvstebø (Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Kantz, 2010), 310.

- 2Mulk Raj Anand, “The Monkey Business or a New Experimental Architecture in India,” typed draft manuscript, undated, cited in Mustansir Dalvi, “Mulk and Modern Indian Architecture,” in Mulk Raj Anand: Shaping the Indian Modern, ed. Annapurna Garimella, Marg (Monograph series; Mumbai: Marg Publications, 2005), 56–57.

- 3See Geeta Kapur, “Partisan Modernity,” in ibid., 28–42. See also Jessica Berman, “Toward a Regional Cosmopolitanism: The Case of Mulk Raj Anand,” MFS Modern Fiction Studies 55, no. 1 (Spring 2009): 142–62.

- 4Mulk Raj Anand, “The Search for National Identity in India,” in Cultural Self-Comprehension of Nations, ed. Hans Köchler (Tübingen/Basel: Horst Erdmannn Verlag, 1978), 73–97.

- 5Mulk Raj Anand, The First Triennale of Contemporary World Art (New Delhi: Lalit Kala Akademi, 1968), 5.

- 6The jury consisted of Anand; the poet and art critic Octavio Paz; Nasayoshi Homma, Curator in Chief, the Museum of Modern Art (Tokyo); Norman Reid, Director, Tate Gallery; Prithwish Neogy, Professor of Fine Arts, University of Hawaii; Dr. A. F. Jakimowicz of the International Association of Art Critics; and R. Von Leyden, contributing editor to Marg, art critic, and connoisseur.

- 7This was intended to offset the lack of large-scale plastic arts, which were prohibitively expensive and difficult to ship.

- 8John Berger in a letter dated January 10, 1968 among a number of letters reproduced in Anand, preface to The First Triennale of Contemporary World Art.

- 9Besides his triennale undertaking, Anand wrote a series of art histories, including_ Persian Painting (1930), The Hindu View of Art (1933), and the controversial Kama-Kala: Some Notes on the Philosophical Basis of Hindu Erotic Sculpture_ (1958).

- 10Anand, preface to The First Triennale of Contemporary World Art.

- 11Ibid., 8.