Karl-Heinz Adler, who died in November 2018, used an abstract geometric approach in both his design and his fine art practices. This essay explores the different reception that Adler received with these two bodies of work in the German Democratic Republic (1949-90), where the official artistic style was Socialist Realism. Given state control and the resistance to alternative aesthetic forms, it is remarkable that Adler’s abstract geometries found their way into the everyday life of East German citizens.

The boundary between Socialist Realism and nonconformist art in the Eastern Bloc is increasingly considered to be fluid, rather than a clear bifurcation of diametrically opposed positions; the career of the East German artist Karl-Heinz Adler is a case in point. On June 8, 2018, the C-MAP Central and Eastern European research group visited Galerie EIGEN+ART in Berlin to view works by the independently minded artist and designer. Adler, born in 1927, lived and worked in the German Democratic Republic (GDR, 1949–90) throughout its existence, and in Germany until his death in 2018. Adler’s work did not fit into the framework of the socialist, realistic art prescribed by the Socialist Unity Party of Germany, and so during its rule, he was not able to exhibit his fine art or to make a living as an artist, similar to other nonconformist artists of the period.1Other nonconformist artists in East Germany included Carlfriedrich Claus (1930–1998) and Hermann Glöckner (1889–1987). The official GDR policy toward artistic production was aligned with Socialist Realism as set out in the 1930s by the Russian Comintern: that cultural production should be relevant to the workers, depict scenes of everyday life, be made in a representational style, and support the aims of the Communist Party. In contrast, Adler created works of geometric abstraction and has done so since the 1950s. It fascinates me that the East German state allowed companies to commission works of design by Adler in this abstract geometric style, even while refusing to support his fine art practice, which displays an identical aesthetic. In its contradiction, Adler’s career in the GDR illustrates the uneven enforcement and changing interpretation at a local level of Socialist Realism, a style of art often mistakenly considered to be as static and monolithic as the then-prevalent busts of Lenin.2Barbara McCloskey speaks to the local debate about Socialist Realism when she writes: “In East(ern) Germany, by contrast, socialist realism became embroiled in highly contentious, party-regulated debates between the artists, the public, and government functionaries over art’s role in a new German cultural order extricated from the infamy of the Nazi past.” Barbara McCloskey, “Dialectic at a Standstill: East German Socialist Realism in the Stalin Era,” Art of Two Germanys: Cold War Cultures (New York: Abrams, in association with the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2009), 105.

Constructivist Adler

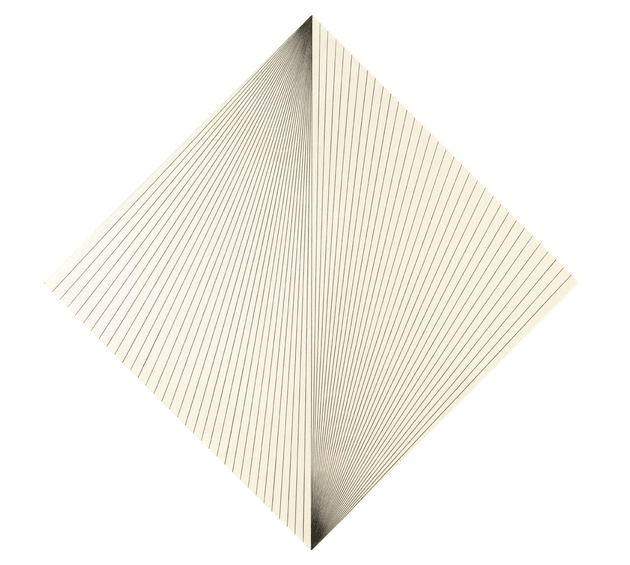

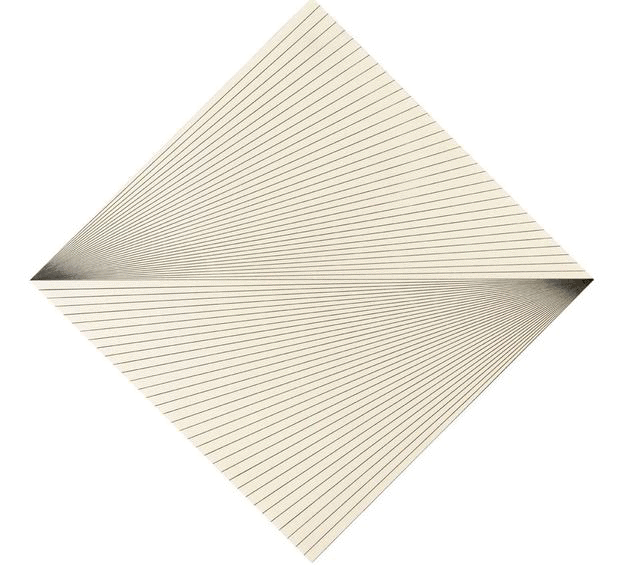

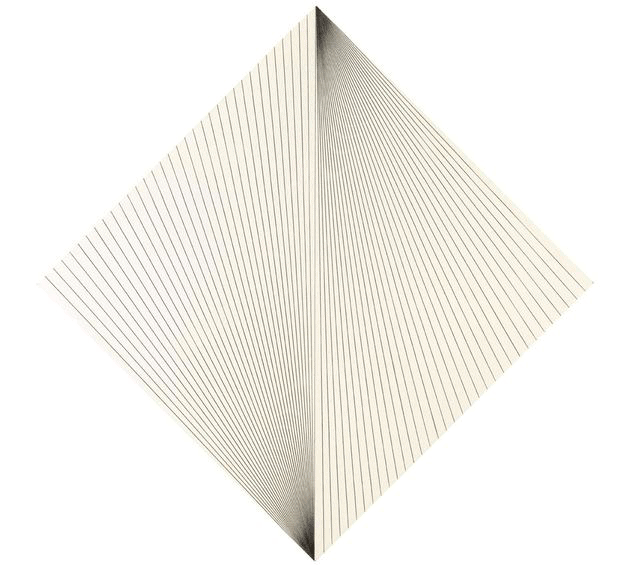

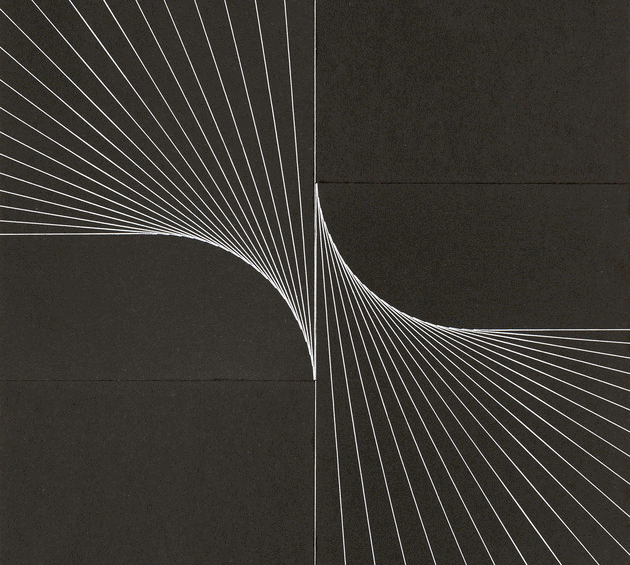

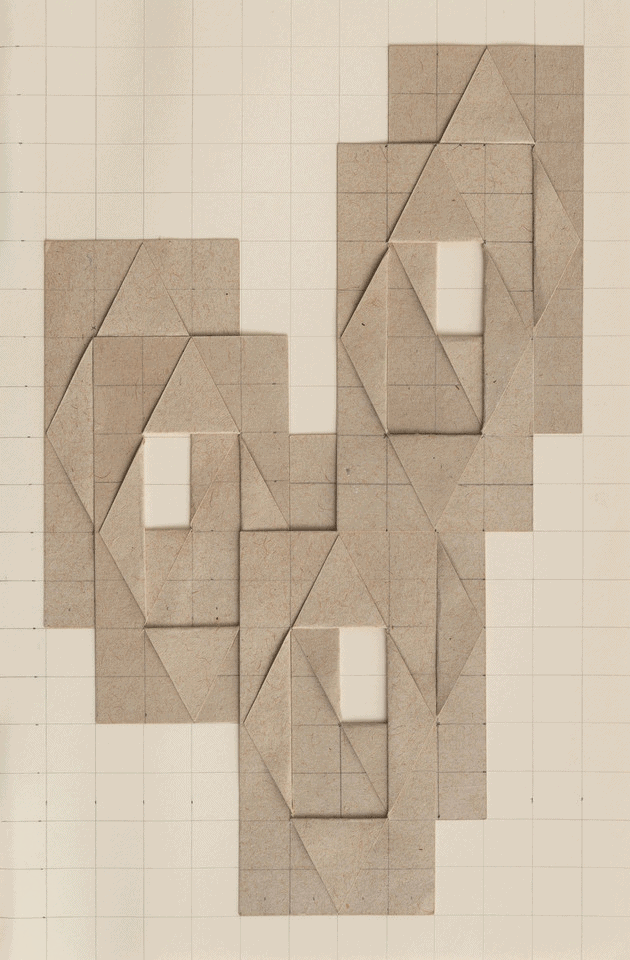

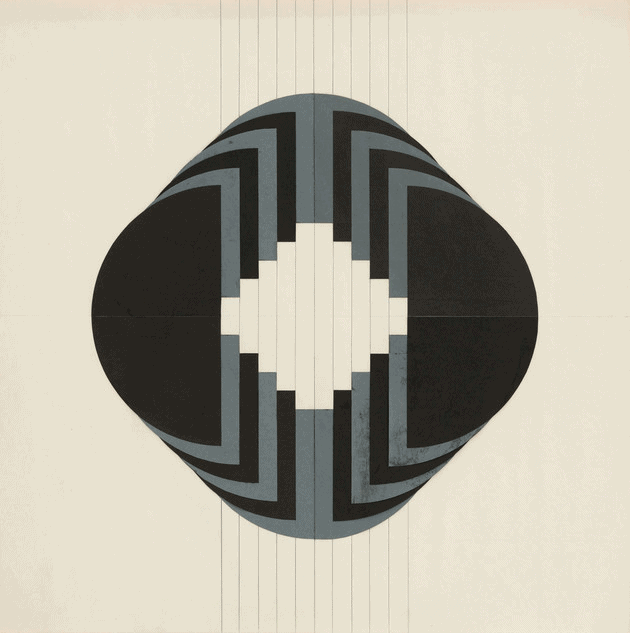

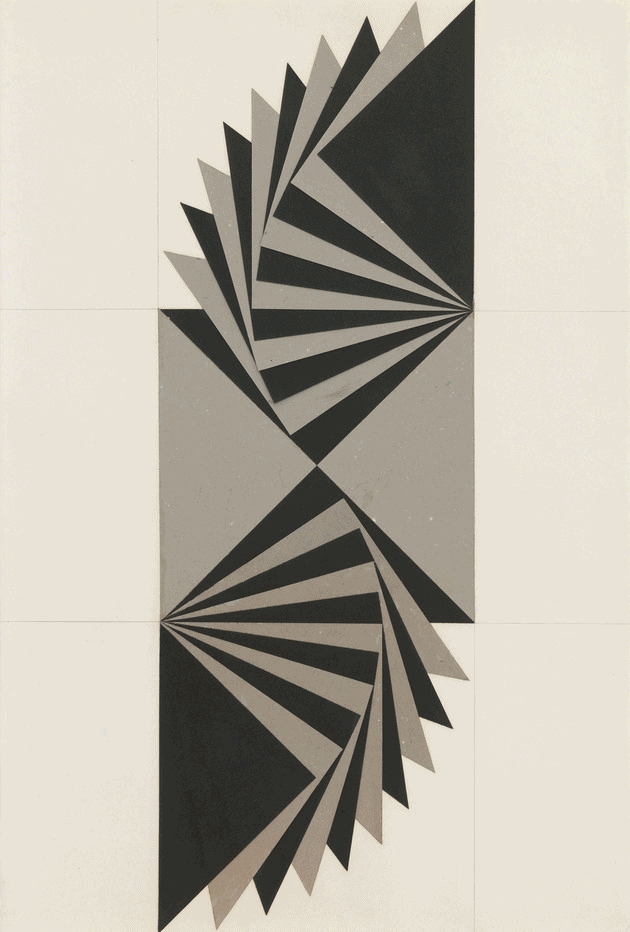

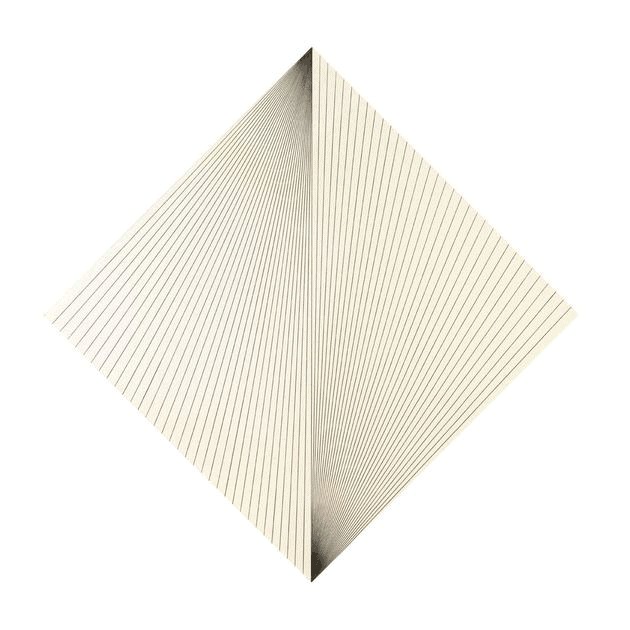

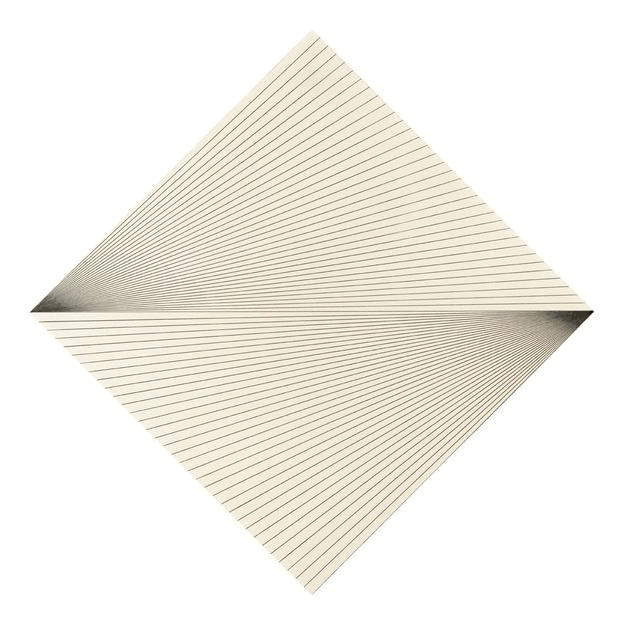

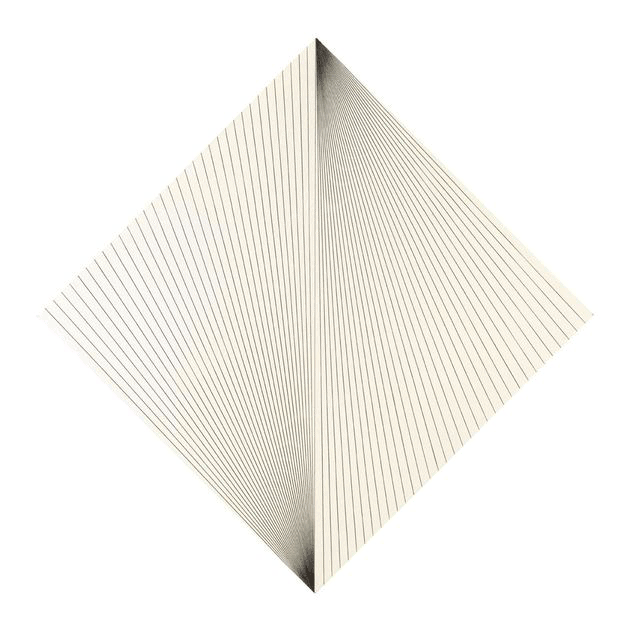

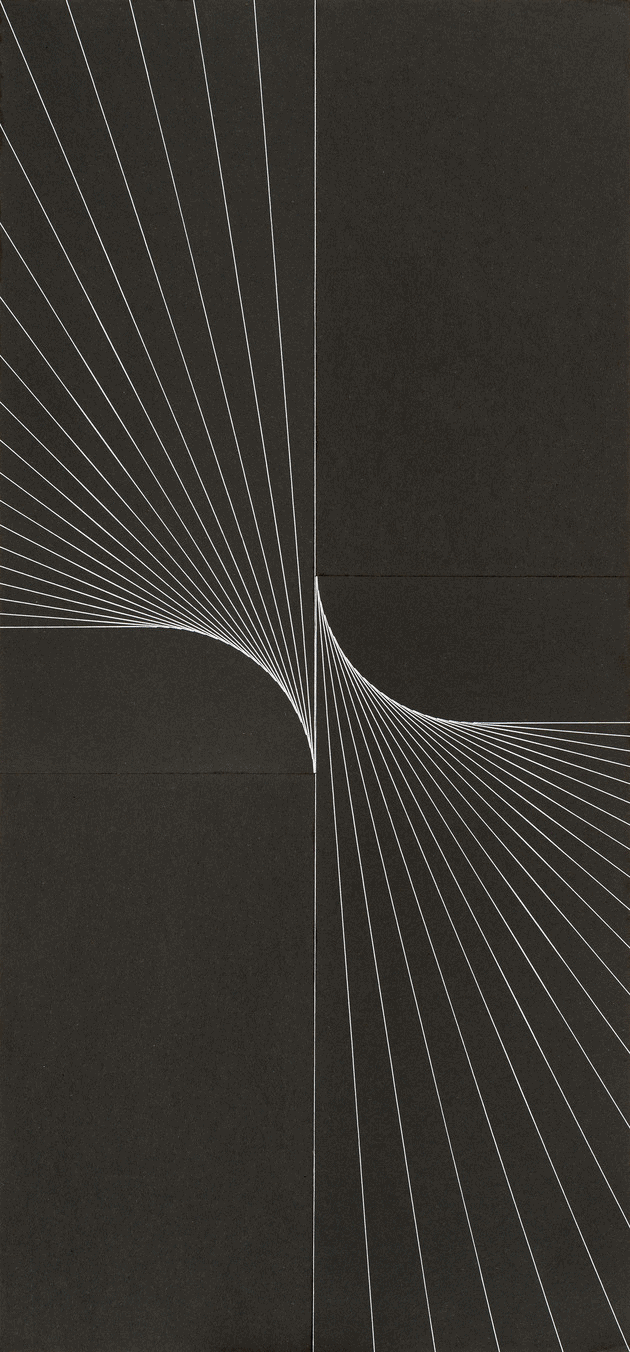

I begin with the format. The format is partitioned on the edges in height and width. One, two, three, four horizontally, one, two, three, four vertically, and then the points are connected. If I want, I apply a grey-white palette in advance and retain the characteristic style. I then take two colors and layer them: one time, two times, three times, four times, five times, six times, seven times. And then work in the opposite direction: one, two, three, four, five. I’ve then achieved my goal: nuancing the color field. The color spaces obtained in this way are divided up according to the rules, based on the network, and then reshaped through my joining the structural components into fascinating, object-like images of organic regularity that differ in shape and color, like we are familiar with in an analogue way from natural phenomena.“3Abstraction Comes from Behind: Karl-Heinz Adler in Conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist,” in Karl-Heinz Adler: Art in the System—The System in Art (Berlin: Spector Books, 2017), 20. —Karl-Heinz Adler

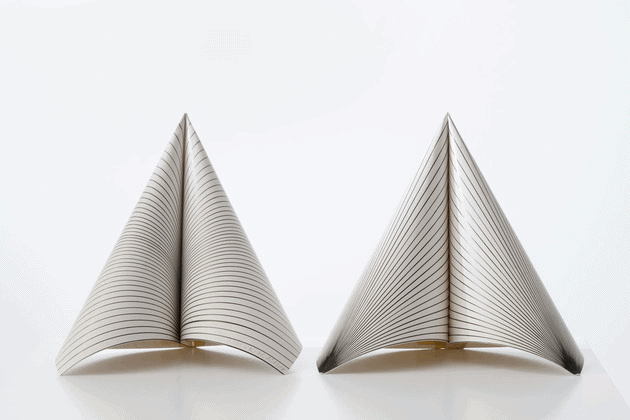

Adler approaches the building of form with simple shapes that can be layered and rotated. He ascribes this analytic and constructive approach to his apprenticeship as a textile designer at a carpet factory.4Ibid. Exploring the variations and rhythms that can be achieved with a single form, Adler cuts shapes out of paper that he then arranges serially on the page in what he calls Schichtungen (layerings). The artist has said of this process, “I wanted to point out the wide range of different possibilities there are in the original form on which these spaces are based.”5Kito Nedo, “Leap into Space,” in Karl-Heinz Adler: systeme/systems (Leipzig/Berlin: Galerie EIGEN + ART, 2016), 8. A reduced color palette, often consisting of only two colors, focuses the viewer’s attention on the dimensionality, depth, and movement that can be created with an economy of means. Adler began to create constructive collages in 1957 and 1958, a little less than a decade after the foundation of the new GDR. To me, this recalls the Russian Constructivist artists who, amid the turmoil of the Russian Revolution of 1917, visually broke down the world to start anew, with a goal of using art to help build a new society. However, in Adler’s case, his works, from their very beginning, existed in tension with the official policy of supported art.

Adler’s early explorations of geometric abstraction occurred in parallel with Minimalism, Op art, and Concrete art, abstract movements that were emerging in the West. Yet he was isolated from these developments to a great degree. While artists whose work was supported by the East German state had some freedom to travel or exhibit in Western Europe, Adler did not. His travel in these years was limited to countries that were politically aligned with the GDR, such as Poland. For Adler, knowledge of Constructivism or its legacy in Europe, such as at the German-based Bauhaus, came more from a limited supply of books and word of mouth.6The Bauhaus, which continued the Constructivist legacy, closed in 1933, and information about it circulated unevenly in East Germany. Adler tells of first hearing of the Bauhaus when he came across a book on it in Walther Löbering’s attic while he was a student at the State Art and Master School of Textile Industry (Staatlichen Kunst- und Meisterschule für Textilindustrie) in Plauen. Adler describes the school in Plauen as a connection to earlier avant-gardes: “The art school in Plauen was a legendary institution. Klee gave lectures there. As a specialized school, art and technical college for the textile industry, it had maintained a very good connection to the Bauhaus earlier on.” “Abstraction Comes from Behind,” 18. Adler has, nevertheless, worked with geometric abstract forms throughout his career. In addition to his early training in textile design, he cites nature as an influence on his forms: “In our developments, we always used a simple grid as a starting point. It then developed and grew organically, as also occurs in nature.”7Ibid., 23. Though Adler was working in a place that limited his exposure to international art trends, it seems that observation of the natural world helped him to pursue abstract and serial forms.

Architectural Decoration

I wanted to make the elements in such a way that they result in new aesthetic design possibilities again and again.8Ibid., 20. —Karl-Heinz Adler

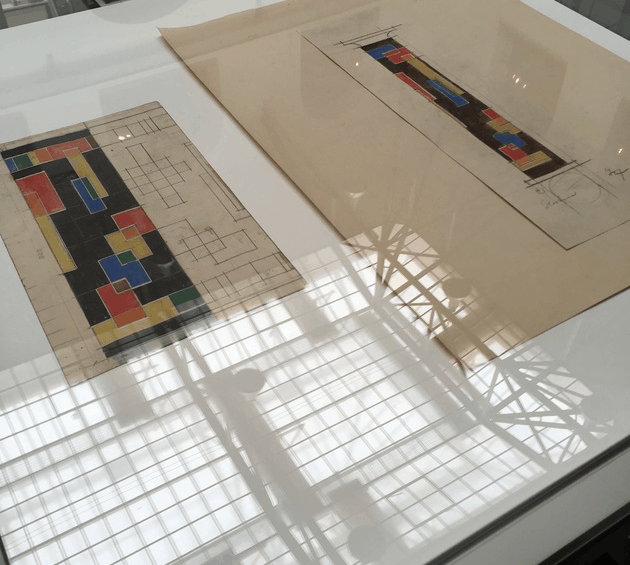

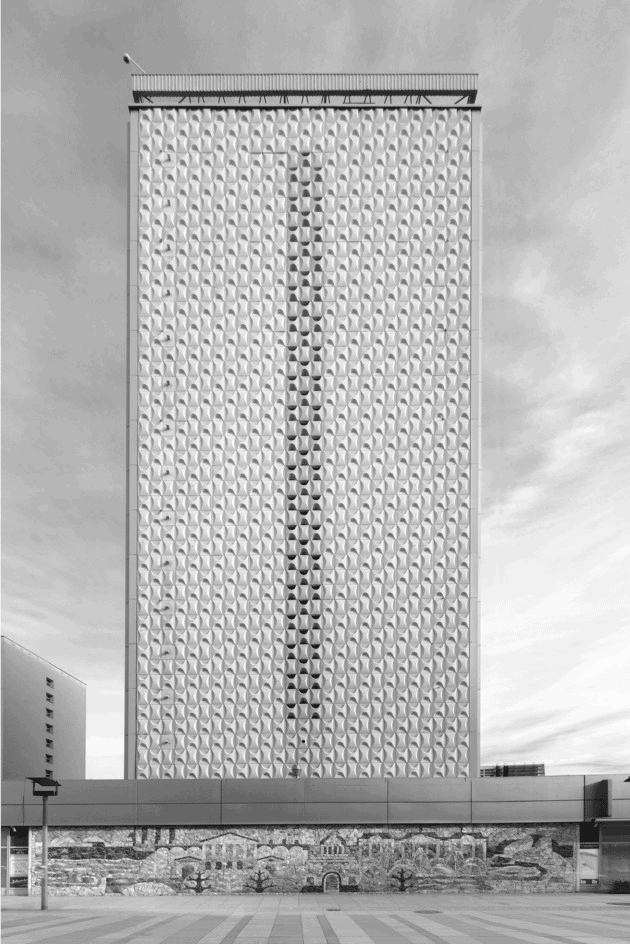

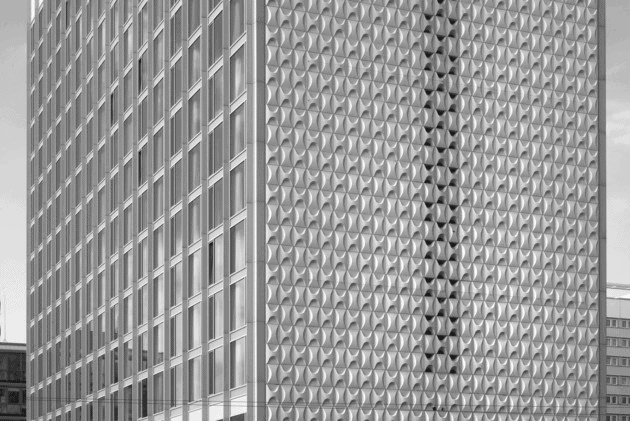

In parallel to his fine art, Adler created systems of architectural decoration that, strongly connected to his abstract, constructivist explorations on paper, were used for public buildings and spaces throughout East Germany. Adler has said that concentrating on environmental design and building-related art “was the easiest way to be able to do something” within the narrow definition of supported art in East Germany.9Ibid. In this way, he contributed to the building of a new society in East Germany—even while choosing an abstract visual language more closely resembling Constructivism than the style of Socialist Realism associated with the Communist revolution in the GDR.

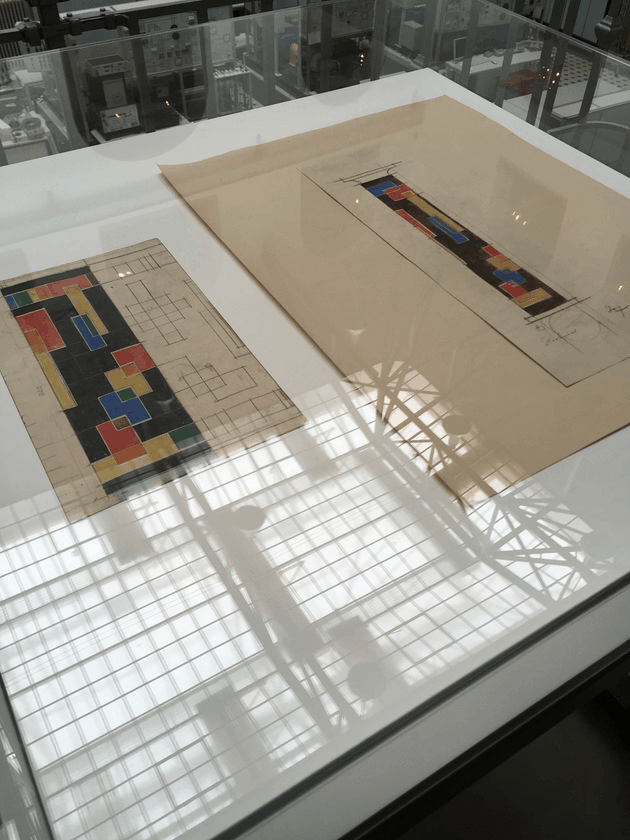

In the 1950s, Adler began working with Friedrich Kracht, an artist who had also trained in the applied arts.10Adler studied at the State Art and Master School of Textile Industry in Plauen before earning a diploma at the Kunstakademie Dresden. Kracht apprenticed as a draftsman and studied at the School of Fine and Applied Arts (Schule für Bildende und Angewandte Kunst) in Dortmund. Karl-Heinz Adler: Art in the System—The System in Art, 117. See also “Projekt Kunst Am Bau in der DDR,“ http://www.kunst-am-bau-ddr.de/die-kuenstler.html. Adler wanted to create productive systems that could be applied to architecture and environmental design. Together, he and Kracht developed modular systems whose parts could be combined by workers and builders in different ways to generate varied abstract surface patterns. This idea of serial systems could be—and was—applied to everyday objects including walls, fountains, and playgrounds. Adler recalls the popularity of the modular construction sets for playgrounds, for example: “The children loved that equipment. It stood in nearly every daycare center and on almost every playground.”11“Abstraction Comes from Behind,” 20.

In 1960, Adler and Kracht joined a production cooperative of visual artists called Kunst am Bau (Art in Architecture) in Dresden.12Nedo, “Leap into Space,” 8. As part of this group, in 1968, the pair developed a concrete breeze-block construction kit called a “Fassadenformsteinsystem” (Façade-form-stone system), which consisted of twelve modular forms.13Breeze blocks are perforated concrete blocks that allow air to pass through. At 23 5/8 x 23 5/8 inches (60 x 60 cm) in size, these concrete sculptural forms could be arranged in numerous combinations determined by the local builder. Ibid. This system was used to produce ornamental concrete surfaces for partitions in public space, facade elements, and decorative columns, among other things. The Berlin-based construction company VEB Stuck und Naturstein put the model into production in 1970, and it soon shaped the appearance of new urban building in East Germany. A 1973 catalogue disseminated information about this façade-form system throughout the GDR, resulting in a burgeoning of concrete walls throughout the country. An example of the Fassadenformsteinsystem appears to this day on the side of the undulating Pullman Hotel Newa in Dresden, a project dating to 1970.

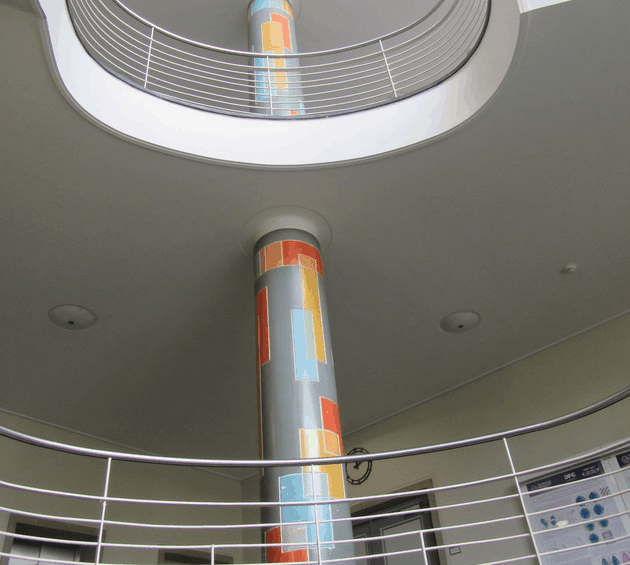

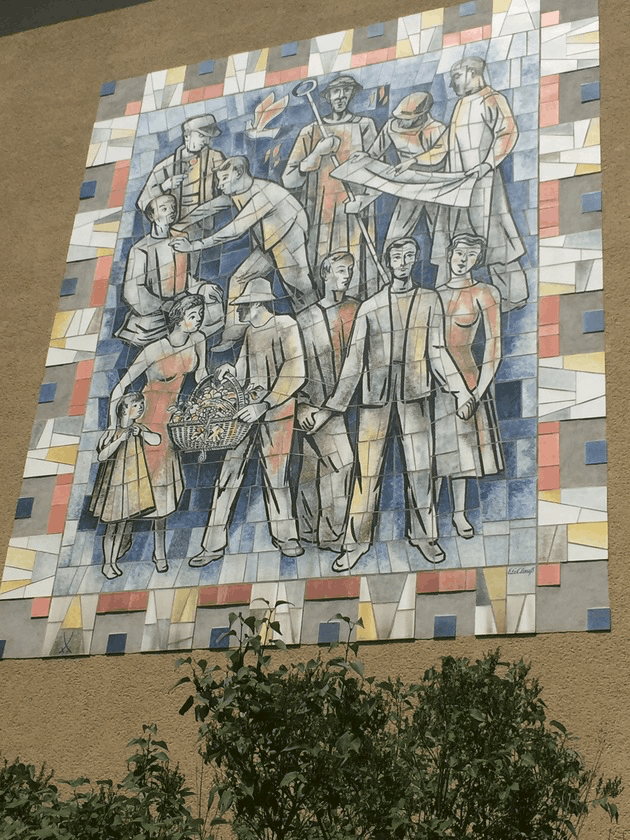

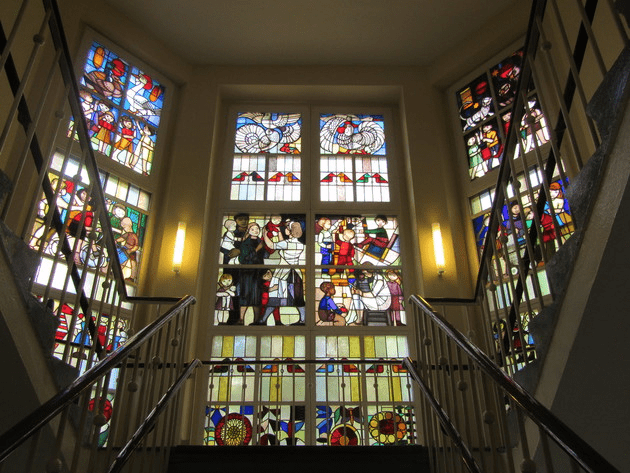

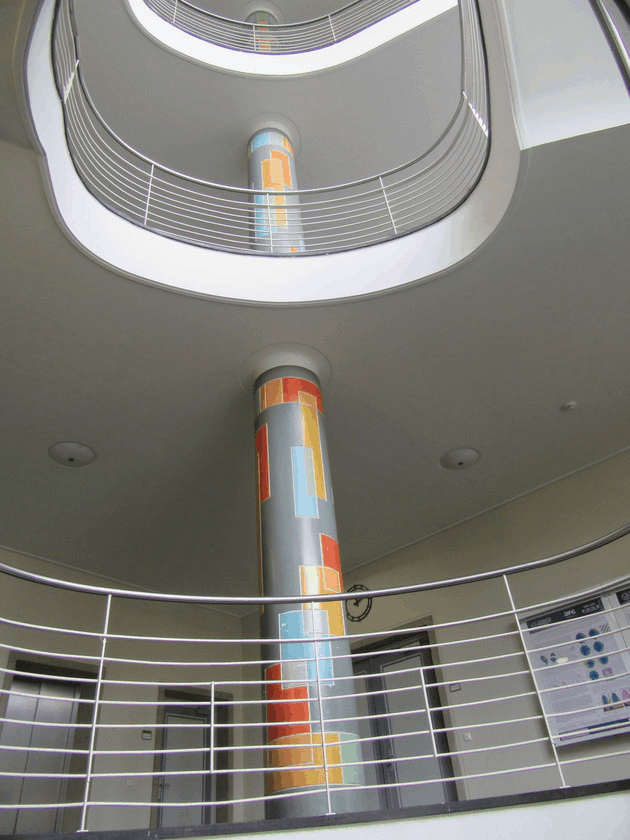

To understand why Adler’s geometric abstraction might seem radical, one could cite examples that the C-MAP Central and Eastern European group saw in the state–planned industrial town of Eisenhüttenstadt, such as a stained-glass window in a former kindergarten and the ceramic mural on the facade of a state–planned apartment building.14Eisenhüttenstadt (originally Stalinstadt) was founded alongside a nearby steel mill in 1950 and served as a model socialist city in the GDR. Both examples correspond to Socialist Realist principles of legible, recognizable forms. One example of abstract architectural decoration that the group encountered during its research trip is Hermann Glöckner’s 1957 color pillar at the Technical University of Dresden. But Glöckner’s nonconformist experiment in geometric building decoration is a single example within a university building, and less visible than the mass-produced designs created through Adler and Kracht’s Fassadenformsteinsystem.

Career Since Reunification

It was only in 1982 that Adler exhibited his works on paper in the GDR. Galerie Mitte, a small gallery in Dresden, displayed Adler’s collages and serial line drawings in a show titled Grafik und entwurfe zur baubezogenen kunst (Artwork and Design for Construction-Related Art), and subsequently featured Adler in a exhibition with Hermann Glöckner in 1984. Even this limited exhibition history reflects the loosening of restrictions since the strict party control of the 1950s.15Christoph Tannert, “Voices of Dissent: Art in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) from 1976 to 1989,” post: notes on modern and contemporary art around the globe, August 9, 2016, http://post.at.moma.org/content_items/843-voices-of-dissent-art-in-the-german-democratic-republic-gdr-from-1976-to-1989. Works on paper by Adler were also exhibited in Malmö in 198416This opportunity came about through the West German painter Gotthard Graubner (1930–2013), who showed some of Adler’s collages to Eje Högestött (1921–1986), then director of the Malmö Kunsthalle, during a studio visit in preparation for the 1984 exhibition of Graubner’s work. “Abstraction Comes from Behind,” 23.; in this and other cases, the artist would smuggle work out of the GDR either by mail or in a suitcase that he carried to Poland.17Ibid. Since the reunification of Germany, Adler’s career as a fine artist has changed significantly. He was appointed guest professor at the highly regarded Dusseldorfer Art Academy in 1990. Prior to his death in November 2018, Adler exhibited more and more widely, including in the 2017 exhibition Karl-Heinz Adler. Ganz Konkret (Karl-Heinz Adler: Very Concrete) at the Albertinuum in Dresden and the 2018 exhibition Karl-Heinz Adler és a magyar absztrakció (Karl-Heinz Adler and Hungarian Abstraction) shown concurrently at two venues in Budapest, the Kassák and Kiscelli Museums.18In an interesting parallel, the part of the exhibition installed at the Kiscelli Museum exhibited Adler’s applied works alongside works by Hungarian contemporaries, including Ferenc Lantos (1929–2014). Lantos nurtured experiments with geometric form in a group of artists known as the Pecs Workshop and worked closely with a nearby enamel factory on large panels for public works. He, like Adler, earned commissions for architectural decoration in an abstract geometric style, despite the overarching policy of Socialist Realism as the supported art style of the state.

A similar approach—the productive building of form through geometric shape—guided Adler’s fine art practice and his design work. The GDR’s decision to allow only the architectural design to operate in the public realm speaks to the limits of what was permissible in the interpretation of Socialist Realism for the building of the East German state. Given the state’s resistance to alternative aesthetics, it is all the more remarkably that Adler impacted everyday life in East Germany through his innovative technical and design products.

- 1Other nonconformist artists in East Germany included Carlfriedrich Claus (1930–1998) and Hermann Glöckner (1889–1987).

- 2Barbara McCloskey speaks to the local debate about Socialist Realism when she writes: “In East(ern) Germany, by contrast, socialist realism became embroiled in highly contentious, party-regulated debates between the artists, the public, and government functionaries over art’s role in a new German cultural order extricated from the infamy of the Nazi past.” Barbara McCloskey, “Dialectic at a Standstill: East German Socialist Realism in the Stalin Era,” Art of Two Germanys: Cold War Cultures (New York: Abrams, in association with the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2009), 105.

- 3Abstraction Comes from Behind: Karl-Heinz Adler in Conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist,” in Karl-Heinz Adler: Art in the System—The System in Art (Berlin: Spector Books, 2017), 20.

- 4Ibid.

- 5Kito Nedo, “Leap into Space,” in Karl-Heinz Adler: systeme/systems (Leipzig/Berlin: Galerie EIGEN + ART, 2016), 8.

- 6The Bauhaus, which continued the Constructivist legacy, closed in 1933, and information about it circulated unevenly in East Germany. Adler tells of first hearing of the Bauhaus when he came across a book on it in Walther Löbering’s attic while he was a student at the State Art and Master School of Textile Industry (Staatlichen Kunst- und Meisterschule für Textilindustrie) in Plauen. Adler describes the school in Plauen as a connection to earlier avant-gardes: “The art school in Plauen was a legendary institution. Klee gave lectures there. As a specialized school, art and technical college for the textile industry, it had maintained a very good connection to the Bauhaus earlier on.” “Abstraction Comes from Behind,” 18.

- 7Ibid., 23.

- 8Ibid., 20.

- 9Ibid.

- 10Adler studied at the State Art and Master School of Textile Industry in Plauen before earning a diploma at the Kunstakademie Dresden. Kracht apprenticed as a draftsman and studied at the School of Fine and Applied Arts (Schule für Bildende und Angewandte Kunst) in Dortmund. Karl-Heinz Adler: Art in the System—The System in Art, 117. See also “Projekt Kunst Am Bau in der DDR,“ http://www.kunst-am-bau-ddr.de/die-kuenstler.html.

- 11“Abstraction Comes from Behind,” 20.

- 12Nedo, “Leap into Space,” 8.

- 13Breeze blocks are perforated concrete blocks that allow air to pass through. At 23 5/8 x 23 5/8 inches (60 x 60 cm) in size, these concrete sculptural forms could be arranged in numerous combinations determined by the local builder. Ibid.

- 14Eisenhüttenstadt (originally Stalinstadt) was founded alongside a nearby steel mill in 1950 and served as a model socialist city in the GDR.

- 15Christoph Tannert, “Voices of Dissent: Art in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) from 1976 to 1989,” post: notes on modern and contemporary art around the globe, August 9, 2016, http://post.at.moma.org/content_items/843-voices-of-dissent-art-in-the-german-democratic-republic-gdr-from-1976-to-1989.

- 16This opportunity came about through the West German painter Gotthard Graubner (1930–2013), who showed some of Adler’s collages to Eje Högestött (1921–1986), then director of the Malmö Kunsthalle, during a studio visit in preparation for the 1984 exhibition of Graubner’s work. “Abstraction Comes from Behind,” 23.

- 17Ibid.

- 18In an interesting parallel, the part of the exhibition installed at the Kiscelli Museum exhibited Adler’s applied works alongside works by Hungarian contemporaries, including Ferenc Lantos (1929–2014). Lantos nurtured experiments with geometric form in a group of artists known as the Pecs Workshop and worked closely with a nearby enamel factory on large panels for public works. He, like Adler, earned commissions for architectural decoration in an abstract geometric style, despite the overarching policy of Socialist Realism as the supported art style of the state.