Carlfriedrich Claus is one of few artists who worked in East Germany that has work in MoMA’s collection. A portfolio of ten prints, together called Aurora, was acquired in 1980, just a few years after the prints were produced and nearly a decade before the Berlin Wall came down. The year prior to the purchase of Aurora, a series of Psychological Improvisations were gifted to the museum by the Kunstammlungen Dresden. Today, the Carlfriedrich Claus archive is kept under the meticulous care of Brigitta Milde at the Kunsammlungen Chemnitz, which the MoMA C-MAP group for Central and Eastern Europe visited in the summer of 2018 on a research trip.

Brigitta Milde has been a curator at the Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz since 1993, and since 1999, the director of its Carlfriedrich Claus archive. From 1982 to 1992, she was head of the Städtische Galerie am Markt in Annaberg-Buchholz, the birthplace and home of Carlfriedrich Claus (German, 1930–1998). Lynn Rother is Senior Provenance Specialist at The Museum of Modern Art in New York. She, too, was born and raised in Annaberg-Buchholz and has been a member of C-MAP’s Central and Eastern Europe group since 2017. Carlfriedrich Claus’s work has been part of the MoMA collection since 1979.

This interview was conducted in German, and translated into English by Anne Posten.

To read the original German, please scroll down.

Lynn Rother: Carlfriedrich Claus lived a secluded life in the small town of Annaberg- Buchholz in the Ore Mountains near the Czech border, yet he corresponded with artists and philosophers from all over the world. Do you see this as contradictory?

Brigitta Milde: Carlfriedrich Claus is a phenomenon. Despite living in a provincial backwater, his art aimed at nothing less than the investigation, depiction, and communication of universal relationships. Relationships between being and consciousness, man and nature, historicity and responsibility for the future, language-thinking processes and extralinguistic-psychic ones. One of the guiding principles of his thought and art was communication. And communication was also something he intensively cultivated personally. He understood his “Sprachblätter” (a term he translated as “speech sheets,” which implies an interest in the acoustic dimension of the visual works) as art in and of themselves, but also as means of communication and a way of learning more about himself (that is, the unconscious, repressed, libidinous aspects of his mind) through the artistic process—and then as a way of exchanging these ideas and experiences with others.

Since communication played such a major role in his work, it’s not surprising that it was also extremely important in his life. Claus needed and sought out exchange with others. In the small town of Annaberg-Buchholz, and also within the ideologically restrictive art world of the German Democratic Republic [GDR], he met with much resistance and so found few suitable communication partners. Instead, he communicated literally worldwide through letters: His contacts extended from Japan (Yuichi Inoue, Niikuni Seiichi) to the United States (Emmett Williams, Dick Higgins), from Russia (Valeri Scherstjanoi) to South America (Guillermo Deisler). He corresponded with art historians (Will Grohmann) and philosophers (Ernst Bloch), artists (Raoul Hausmann, Jean [Hans] Arp, Fritz Winter, Bernard Schultze) and writers (Franz Mon, Ilse and Pierre Garnier, Christa Wolf). The Carlfriedrich Claus archive, which is housed in the Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz, alone comprises 22,000 letters.

LR: Would you say that life as an artist was made difficult for him in the GDR, despite the fact that he saw himself as a Communist? How did he reconcile this?

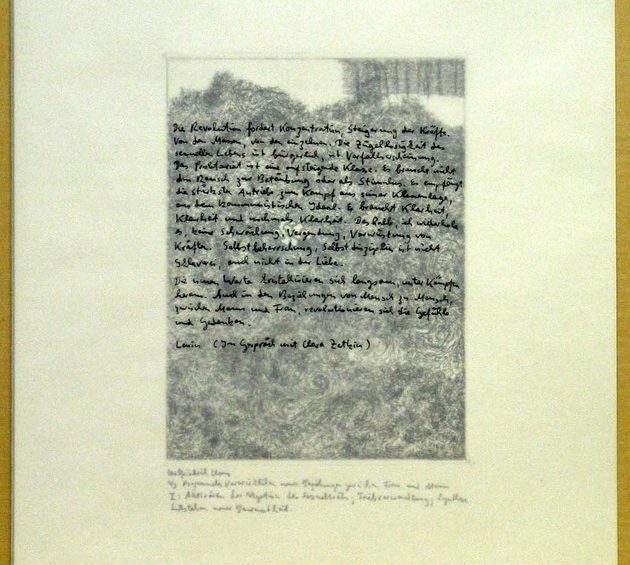

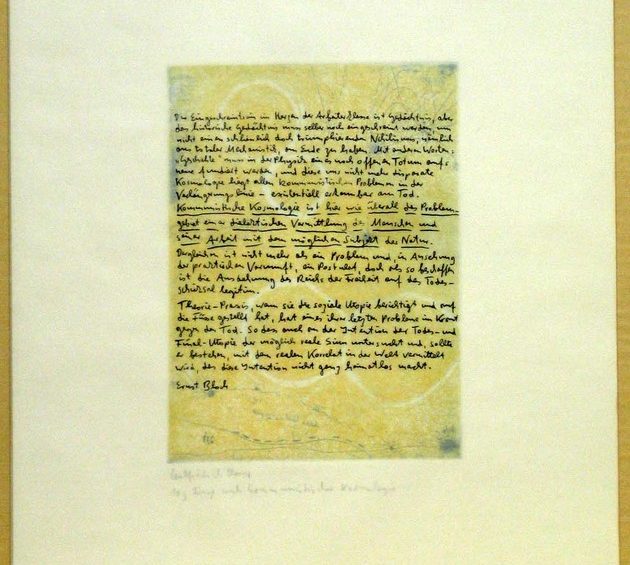

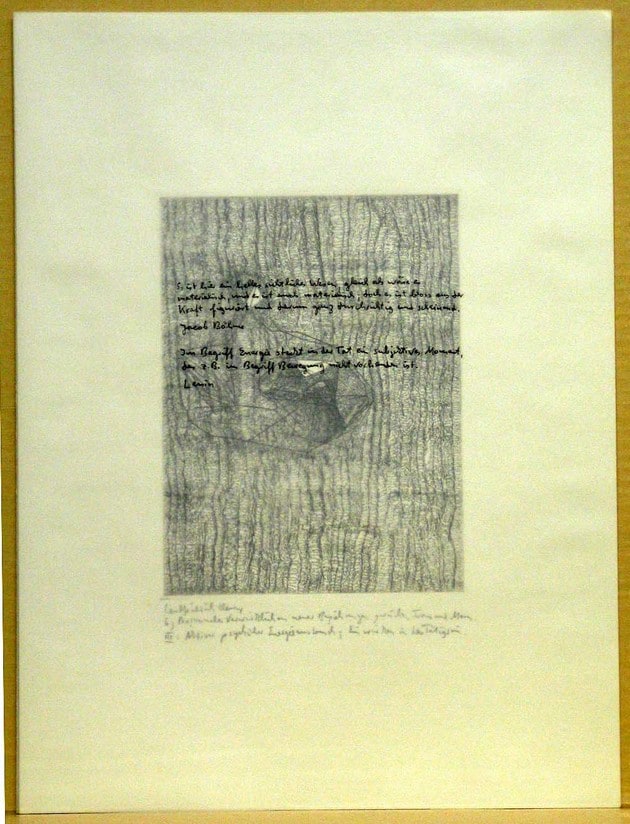

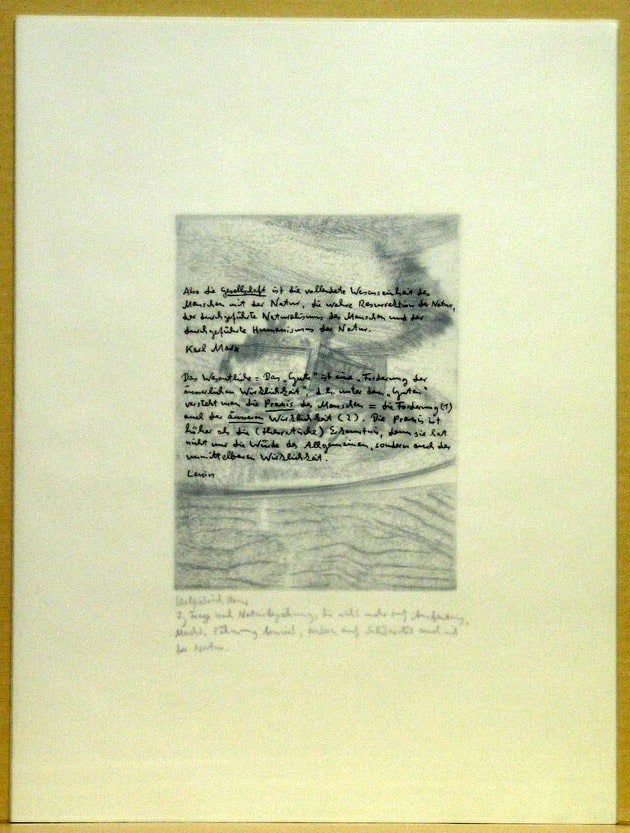

BM: Yes, Carlfriedrich Claus understood himself as a Communist, but his worldview had little to do with the ideologically rigid model of thought that was understood as “Communist” in the Eastern bloc. Claus was inspired less by Marx than by Ernst Bloch, one of the many philosophers branded a “dissident” in the GDR. From Ernst Bloch, Claus was inspired to an interest in mysticism, speculative interpretations of the world, and techniques of religious ecstasy—all of which were frowned upon under Socialism. I think, rather, that through intensive religious philosophical, philological, and psychological study, he developed his own unique worldview, according to which every individual, in transforming him- or herself, can take part in bettering the world as a whole. His art was a means of recording these inner changes and, as I said before, also a medium through which to communicate these possibilities to others.

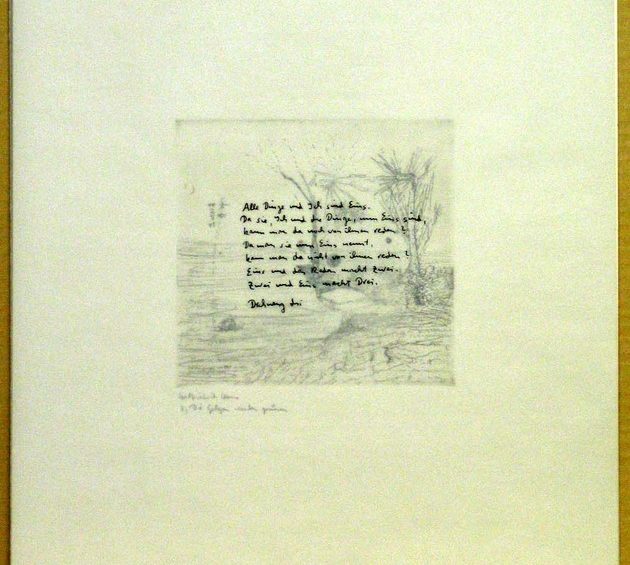

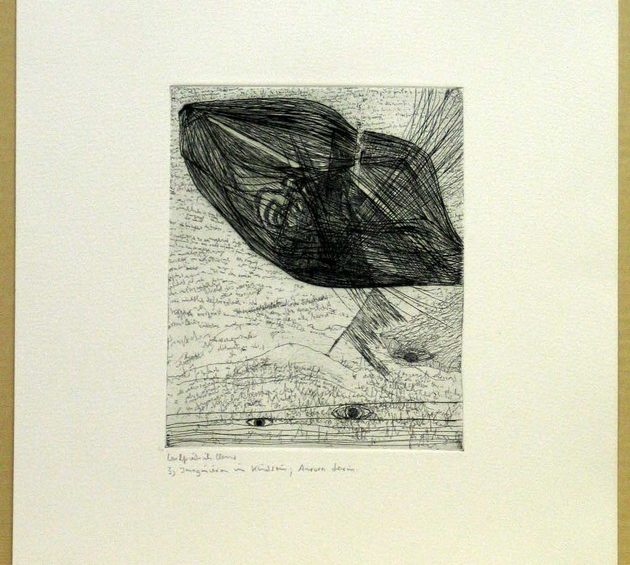

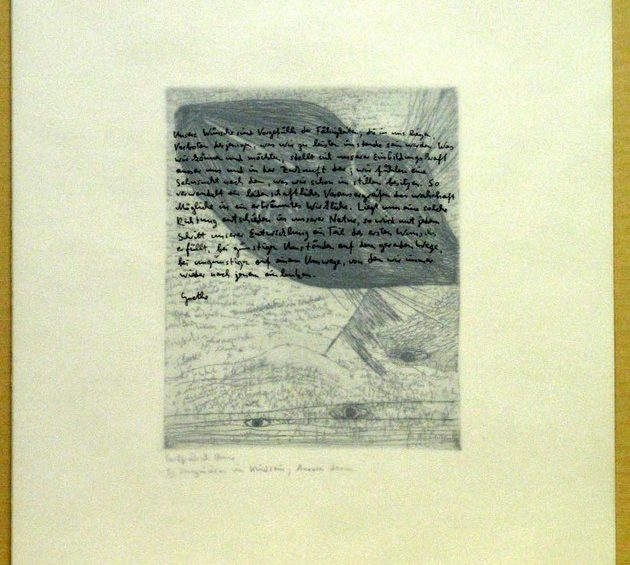

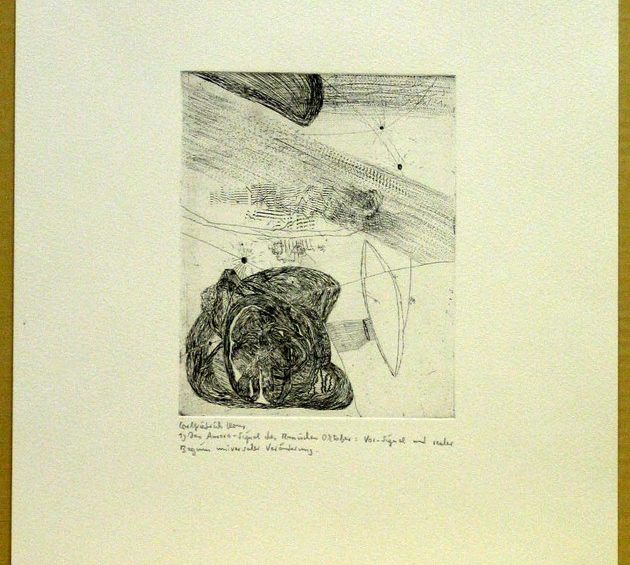

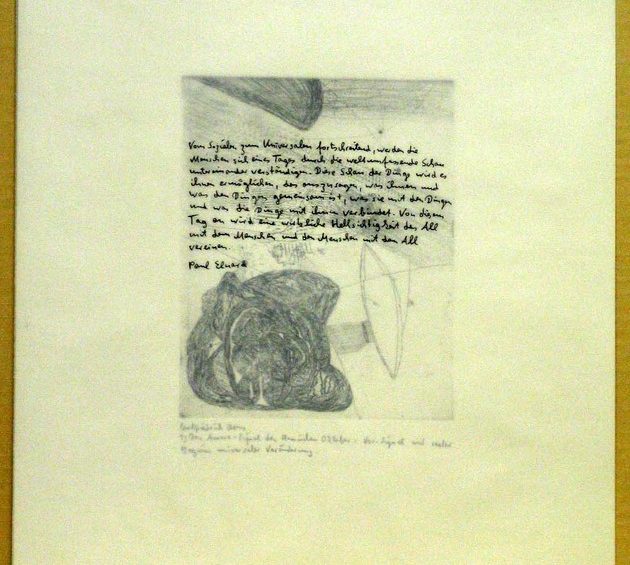

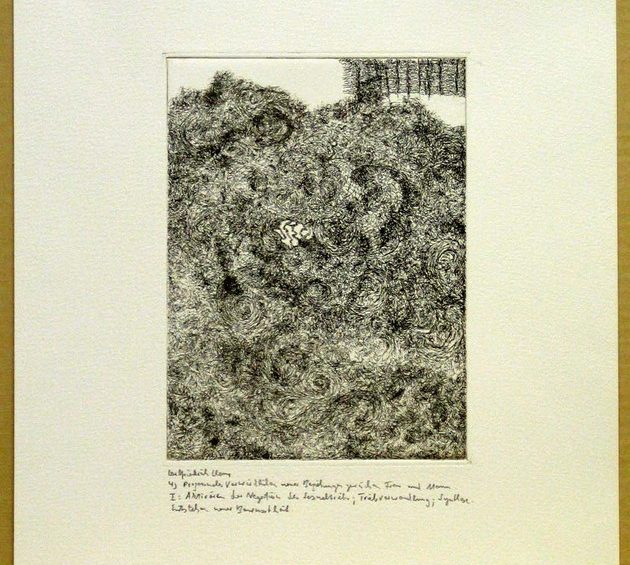

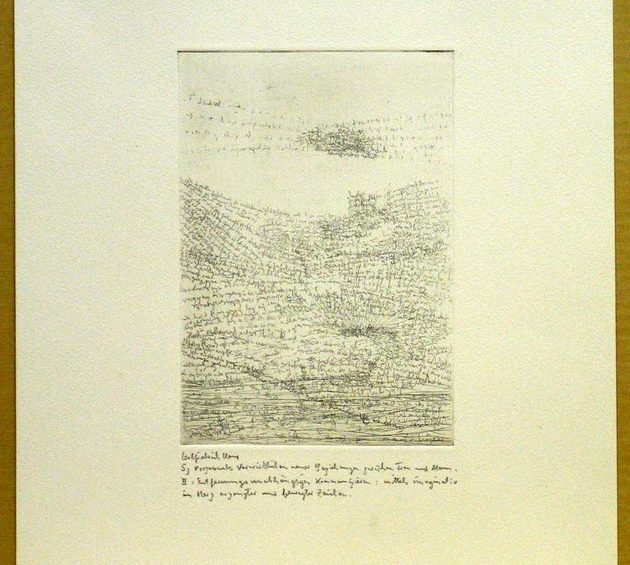

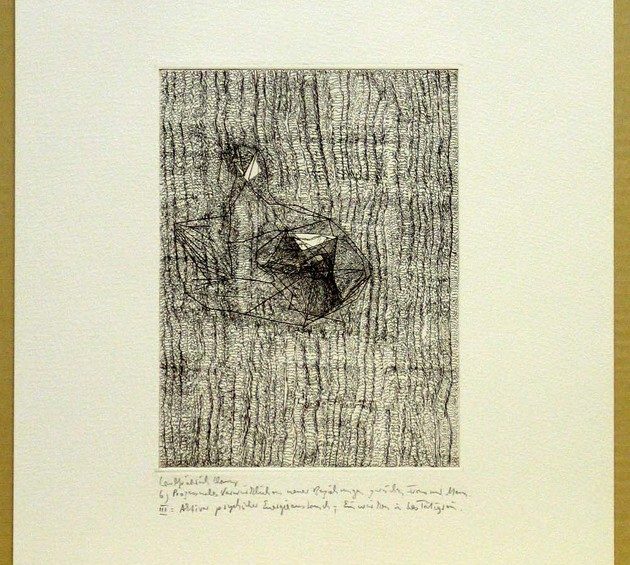

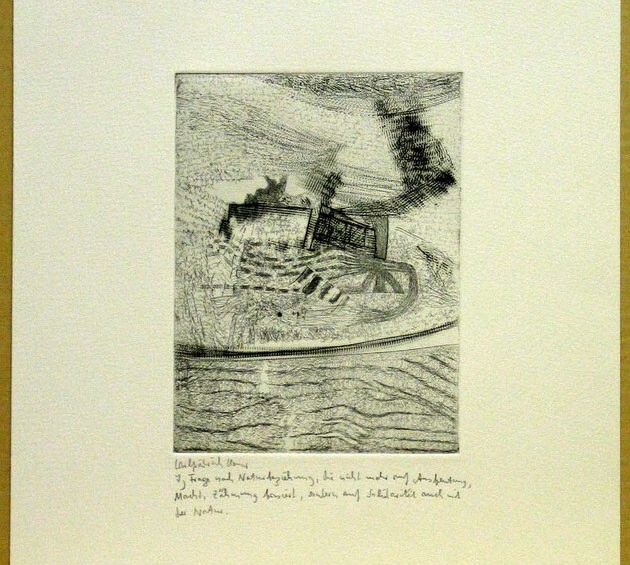

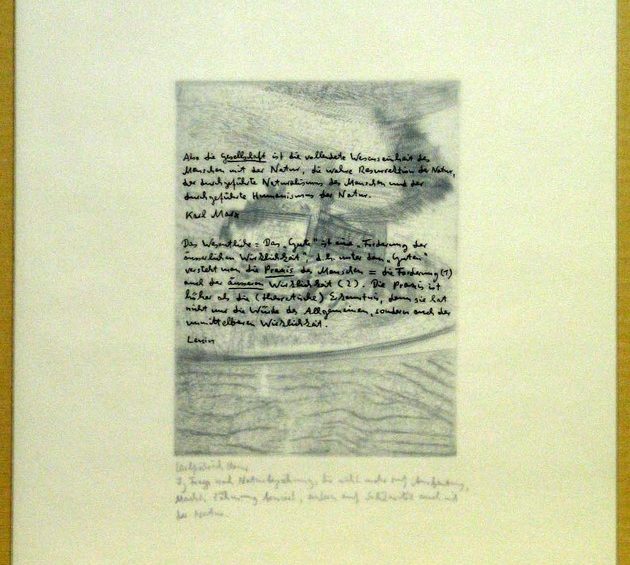

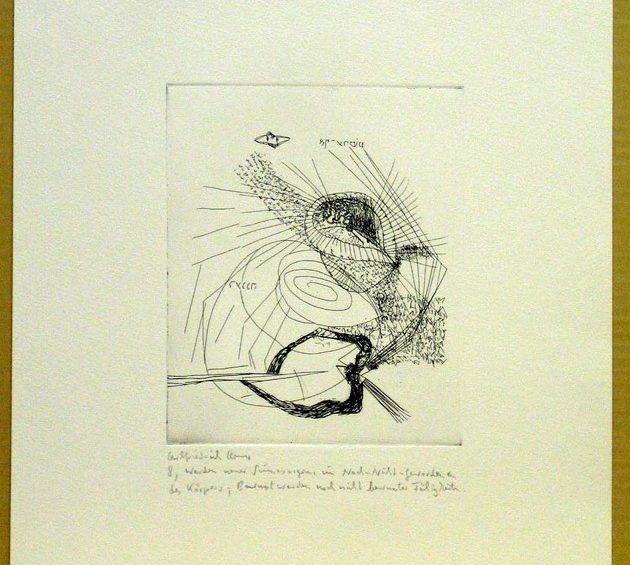

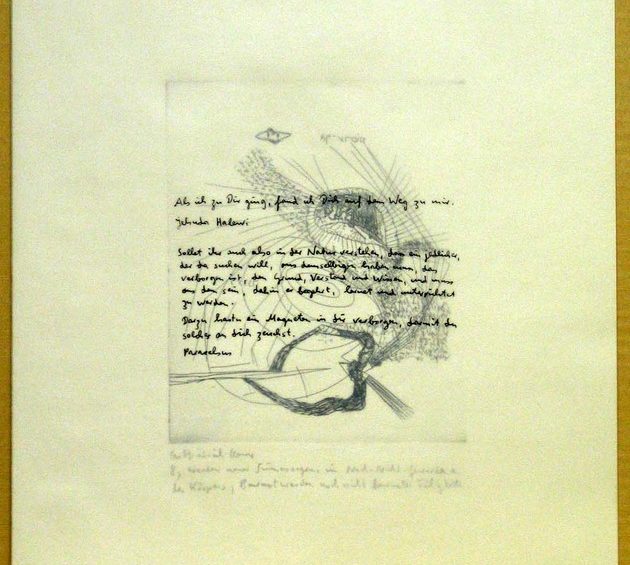

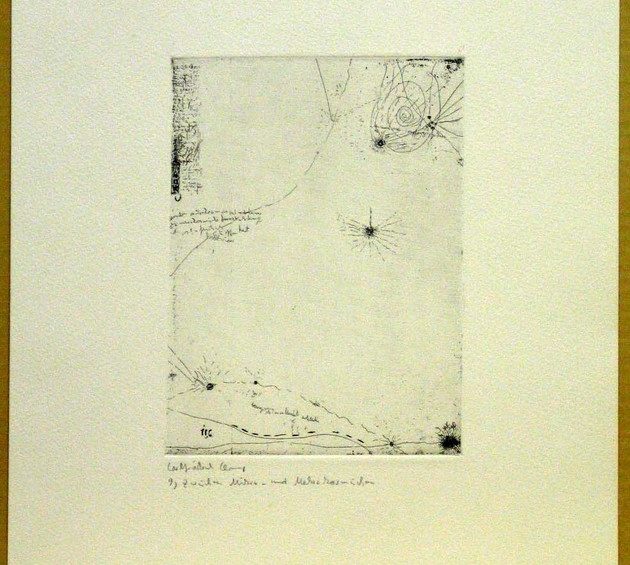

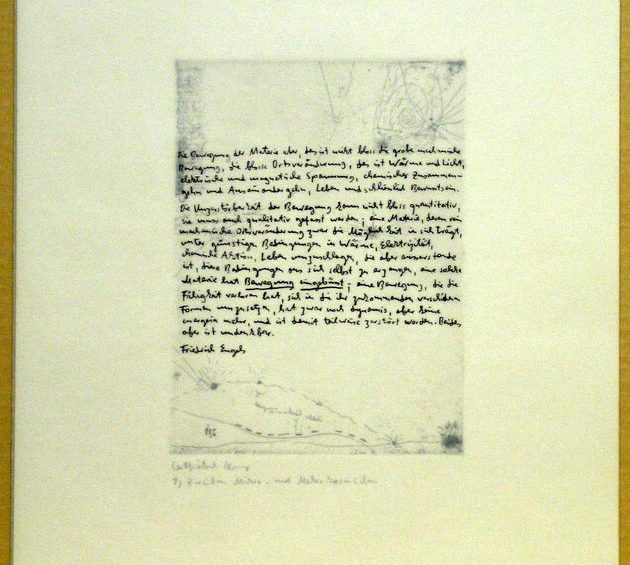

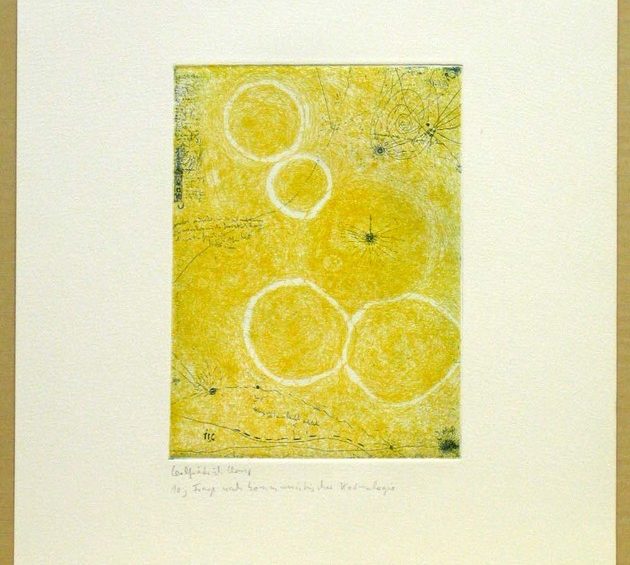

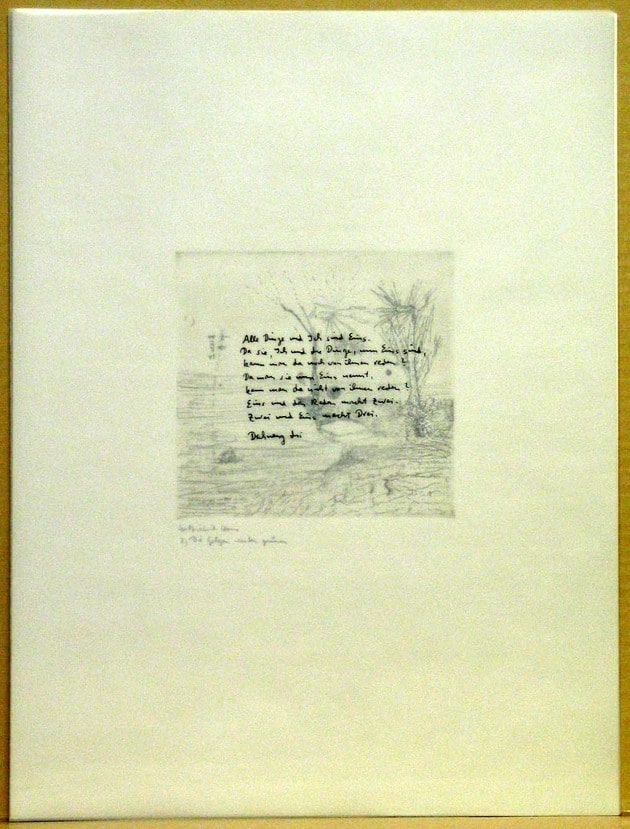

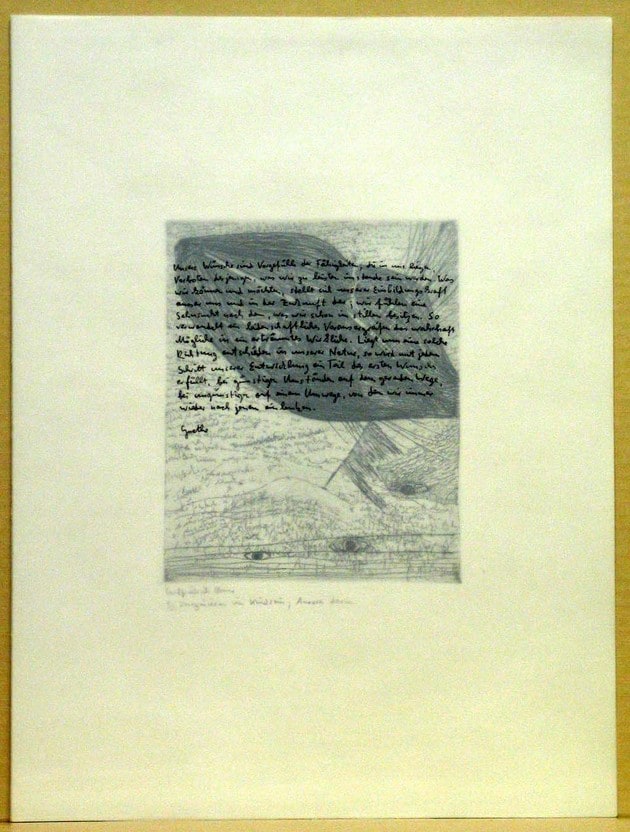

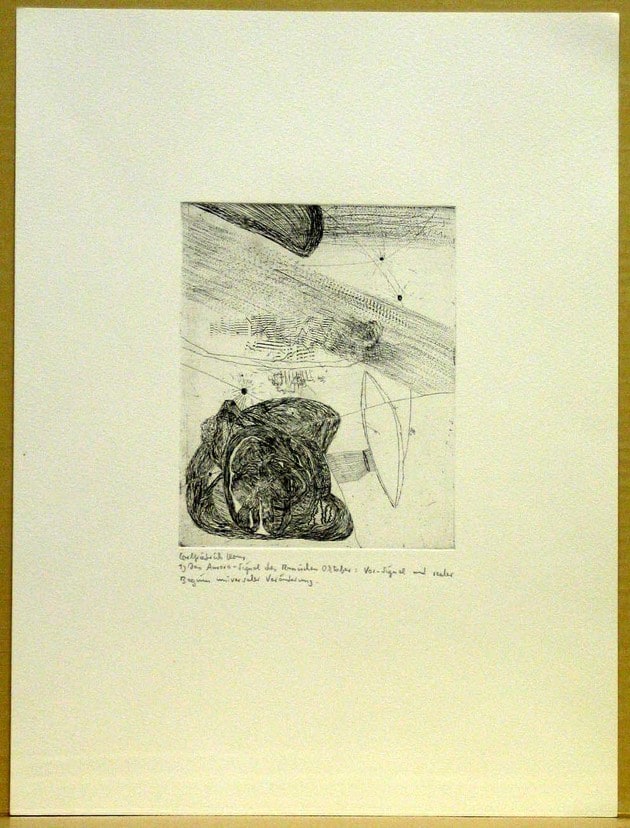

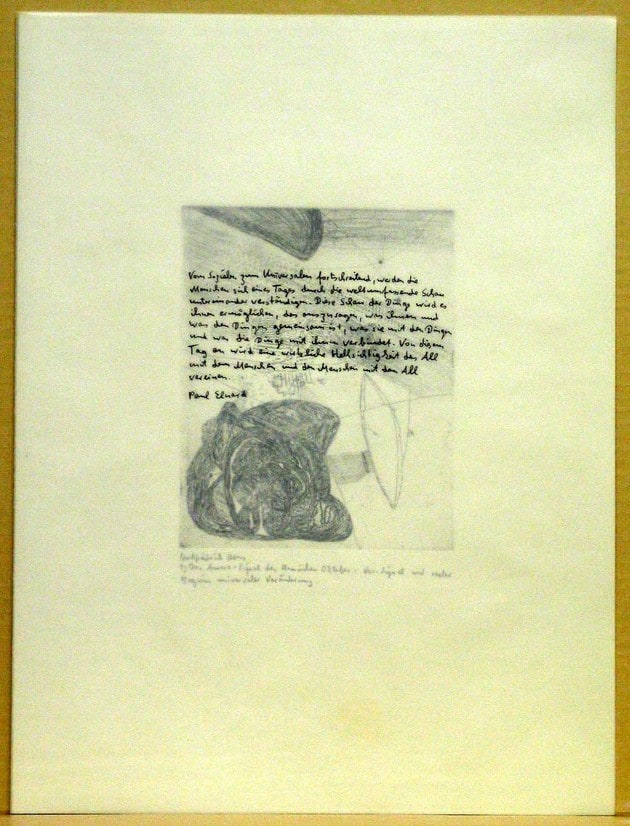

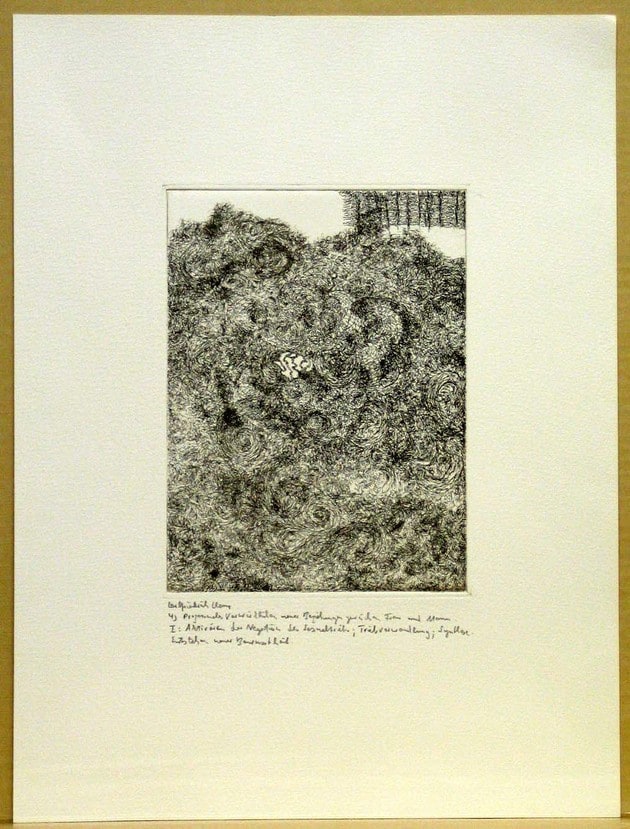

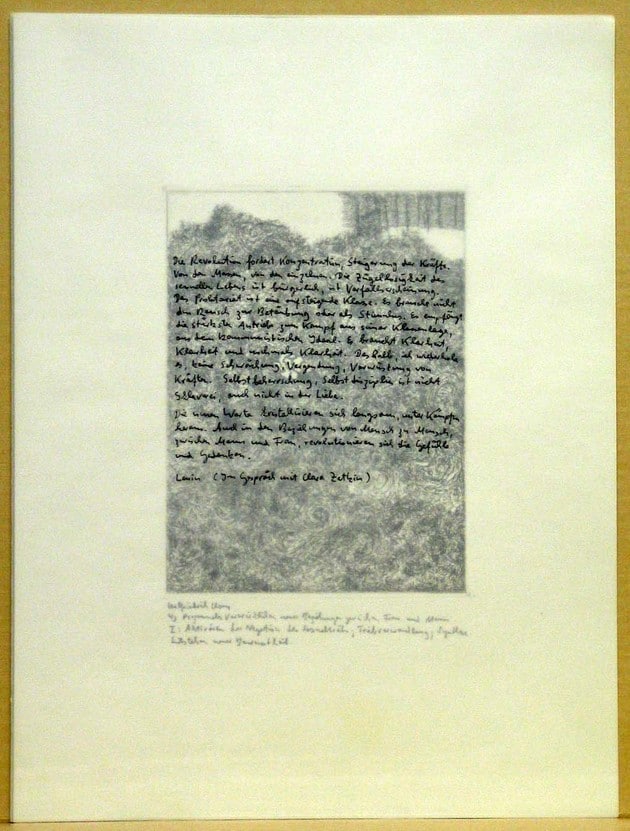

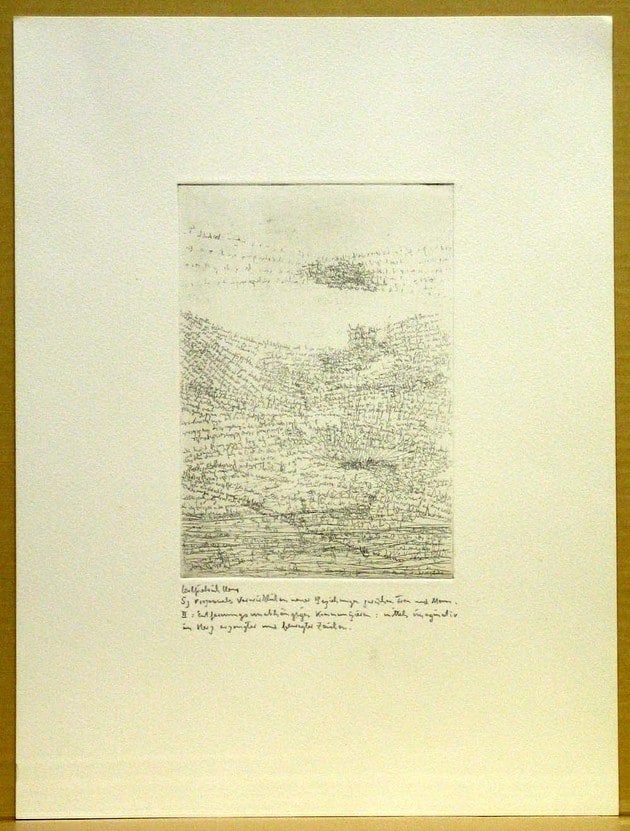

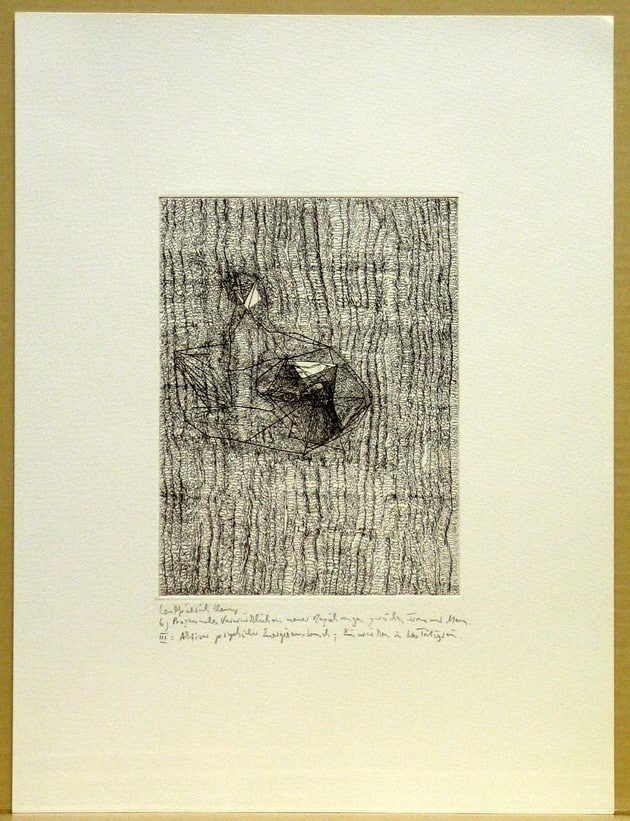

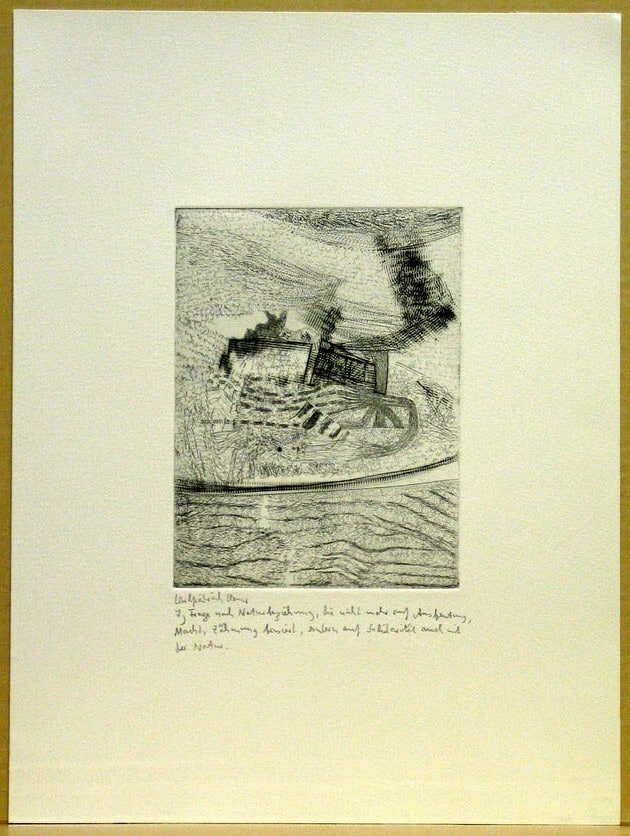

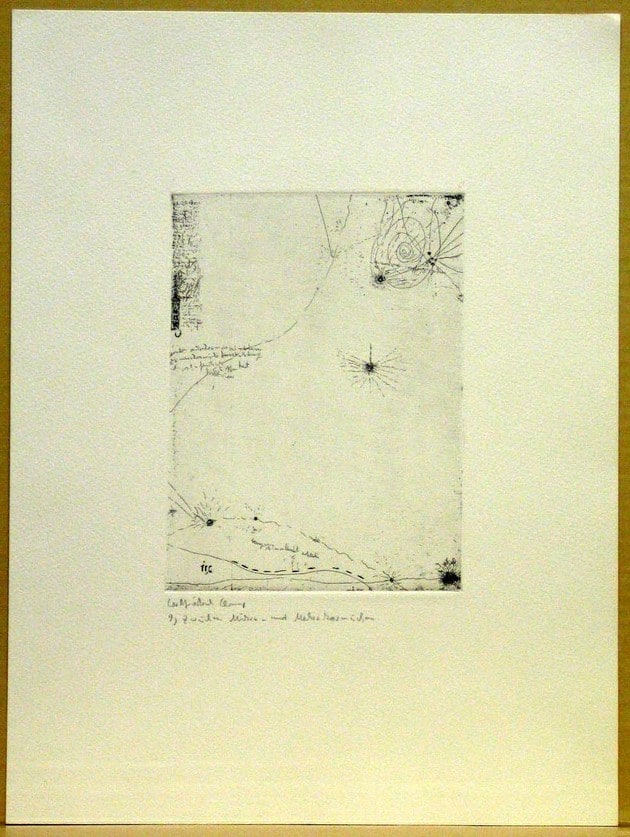

The fact that Claus did not receive any official recognition in the GDR until the mid- 1970s had to do, above all, with his art. His “Sprachblätter” simply bore no relationship to Socialist Realism. Claus’s background was in the written word, though he had a broad understanding of “text.” He covered both sides of transparent paper so thickly and complexly with writing and drawing that the writing became illegible and thus reverted to image—to a largely abstract image that now and then features legible verbal passages and allows associations with landscapes or physiognomies and, above all, to an image that is not fixed, but rather is, in and of itself, a kind of process, or dialogue of written fragments and traces of drawings between the front and back of the paper. These “Sprachblätter” are not finished objects, but rather have to be unlocked, decoded, and completed by the recipient through the process of looking and reading. In this way, they are the very opposite of state–sponsored Socialist Realism, with its claim to truth.

LR: Graphic artworks from the GDR are generally highly regarded today. They were created outside of the official state–sponsored fine art and are superior in quality and density. As a graphic artist, isn’t Carlfriedrich Claus actually a typical representative of this milieu?

BM: Yes and no. As a whole, the high standard of GDR print work is striking. The small format was less useful for ideological themes and instead fostered formal experimentation and artistic innovation. Perhaps it is for this reason that it was in the realm of graphic arts that fresh, original pieces of great technical brilliance and excellent craftsmanship were created throughout the country. Yes, it’s true that Carlfriedrich Claus was inspired by these fertile surroundings. When he turned to printmaking around 1970, he could rely on the technical experience of artists like Max Uhlig or Thomas Ranft, who printed his lithographs and etchings. Ranft was particularly instrumental in printing Aurora [1975–77, published 1977], a portfolio of ten etchings (a copy of which is part of the MoMA’s collection).

On the other hand, Claus’s print works are so singular stylistically, methodologically, and in their intellectual depth that they largely defy comparison with other sophisticated print work from the GDR.

LR: If Carlfriedrich Claus can’t be sufficiently explained in the context of GDR art, where should we look for points of reference? To Dada or Paul Klee? To Mail Art?

BM: Dada was enormously important to Carlfriedrich Claus, particularly in his earlier years. Dada was nonconformist and rebellious, it was intermedial, and it was untainted by any connection to Nazism—which was extremely important in the years after World War II. Claus had a very lively, stimulating correspondence with Raoul Hausmann—though it was limited to the year 1960, after which they quarreled. Hausmann was a bitter and complicated person.

Paul Klee was something of a stylite in the independent culture scene—he was impossibly distant (who had ever seen an original?), but greatly admired. It’s probably rare to find as many Klee-lovers per capita as there were among the critical minds of the GDR! [Laughs.] Claus dealt with Klee intensively and analytically throughout his own life. He wrote a wonderful text about his relationship to Klee on the occasion of the first major exhibition of Klee’s work in the GDR, which was held at the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen in Dresden in 1985.

I can say generally that the avant-garde art of the 1950s and early 1960s was an important model for Claus, without inspiring him to emulate it stylistically. But the formal radicality, the uncompromising and utopian nature of this art fascinated him— as it did many of his generation in both the East and West. Claus was also artistically connected to representatives of concrete and visual poetry, among whom the intermingling of theory in the creative process was common. And his working style also paralleled the textualization of discourse that was the trend in this milieu. He had exhibitions in the context of this circle, and he published in their periodicals. So inevitably, there were commonalities between his work and Fluxus or Mail Art.

LR: Did Carlfriedrich Claus influence his fellow artists? Does he still have some kind of influence on the work and trends of today?

BM: When the restrictive cultural policies of the GDR relaxed in the 1970s, a lively, creative, nonconformist art scene developed in what was then called Karl-Marx- Stadt (now Chemnitz). In 1977, Michael Morgner, Thomas Ranft, Dagmar Ranft- Schinke, and Gregor Torsten Schade (later known as Gregor Torsten Kozik) sought out collaboration with Carlfriedrich Claus. They convinced him to join the artist group CLARA MOSCH, which was active until 1982 and reached an audience far outside the region, gaining recognition for exhibitions, land art, and process-oriented art forms. Even in this group, though, Claus was an outsider—but above all, he was recognized as a kind of spiritus rector.

He also exercised a less direct but lasting influence on the younger artists who turned away from the GDR entirely, choosing instead to blithely and unreservedly pursue their own intentions. Olaf Nicolai, for example, sees Claus as one of the very few proponents of conceptual artistic work. He is impressed by the freedom and internationality of Claus’s work, as well as by its intermediality and complexity—and by the natural connection between theory and art

Brigitta Milde ist seit 1993 Kuratorin in den Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz und seit 1999 Leiterin des dortigen Carlfriedrich Claus-Archivs. Von 1982 bis 1992 war sie Leiterin der Städtischen Galerie am Markt in Annaberg-Buchholz, dem Geburts- und Schaffensort von Carlfriedrich Claus. Lynn Rother ist Senior Provenance Specialist am Museum of Modern Art in New York und seit 2017 Teil von C-Map Central and Eastern Europe (und in Annaberg-Buchholz geboren und aufgewachsen). Carlfriedrich Claus ist seit 1979 in der Sammlung des Museum of Modern Art vertreten.

Lynn Rother: Carlfriedrich Claus hat ein abgeschiedenes Leben in der erzgebirgischen Kleinstadt Annaberg-Buchholz nahe der tschechischen Grenze geführt, andererseits mit Künstlern und Philosophen in der ganzen Welt korrespondiert. Sehen Sie darin einen Widerspruch?

Brigitta Milde: Carlfriedrich Claus ist ein Phänomen. In der äußersten Provinz lebend, zielte seine Kunst auf nichts Geringeres, als universelle Zusammenhänge zu erkunden, darzustellen und zu kommunizieren. Zusammenhänge von Sein und Bewusstsein, Mensch und Natur, Geschichtlichkeit und Zukunftsverantwortung, Sprachdenken und außersprachlichen psychischen Vorgängen. Ein zentraler Begriffseines Denkens und seiner Kunst war Kommunikation. Und Kommunikation hat er selbst intensiv gepflegt. Seine „Sprachblätter“ (Claus selbst hat den Begriff übersetzt mit „speech sheets“ und dabei auch die akustische Dimension der visuellen Arbeiten im Blick gehabt) also noch einmal: seine „Sprachblätter“ verstand er als autonome Kunst, zugleich aber als Mittel der Kommunikation, um im Prozess der künstlerischen Arbeit über sich selbst (seine inneren unbewussten, verdrängten, triebhaften, mentalen Anteile) mehr zu erfahren – und um anhand des fertigen Objekts mit anderen seine Ideen und Erfahrungen auszutauschen.

Wenn Kommunikation eine solche Rolle in seinem Werk spielte, wundert es nicht, dass sie auch lebenspraktisch für ihn äußerst relevant war. Claus brauchte und suchte den Austausch. Innerhalb der Kleinstadt Annaberg-Buchholz, aber auch innerhalb des ideologisch einengenden Kunstsystems der DDR stieß er auf viel Ablehnung und fand nur wenige geeignete Kommunikationspartner. Stattdessen kommunizierte er brieflich wirklich weltweit: von Japan (Inoue Yūichi, Niikuni Seiichi) bis in die USA (Emmett Williams, Dick Higgins) von Russland (Valeri Scherstjanoi) bis Südamerika (Guillermo Deisler) reichten seine Kontakte; Kunsthistoriker (Will Grohmann) und Philosophen (Ernst Bloch), Künstler (Raoul Hausmann, Hans Arp, Fritz Winter, Bernard Schulze) und Literaten (Franz Mon, Ilse und Pierre Garnier, Christa Wolf) korrespondierten mit ihm. Das Carlfriedrich Claus-Archiv, das sich in den Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz befindet, umfasst allein 22.000 Briefe.

LR: Würden Sie sagen, dass ihm sein Leben als Künstler in der DDR schwer gemacht wurde, obwohl sich Claus doch selbst als Kommunist sah? Wie ist er mit diesem Widerspruch umgegangen?

BM: Ja, Carlfriedrich Claus begriff sich als Kommunist, aber mit dem ideologisch starren Denkraster, das man im Ostblock unter „kommunistisch“ verstand, hatte sein Weltbild eigentlich wenig zu tun. Mehr als von Marx war Claus von Ernst Bloch inspiriert, einem in der DDR als „Abweichler“ gebrandmarkten Philosophen. Von Ernst Bloch übernahm er das Interesse an Mystik, spekulativen Weltdeutungen, religiösen Ekstasetechniken – alles im Sozialismus verpönte Fragestellungen. Ich glaube eher, dass Claus aus intensiven philosophischen, religionsphilosophischen, sprachwissenschaftlichen und psychologischen Studien ein ganz eigenes Weltbild entwickelt hat, wonach jeder Einzelne, sich selbst verändernd, an der Verbesserung des Weltganzen mitgestalten kann. Seine Kunst war ihm Mittel, diese inneren Veränderungen zu protokollieren, und, wie bereits gesagt, gleichzeitig Medium, um mit anderen diese Möglichkeiten zu kommunizieren.

Dass Claus bis Mitte der 1970er Jahre keine offizielle Anerkennung in der DDR fand, hatte vor allem mit dieser seiner Kunst selbst zu tun. Seine „Sprachblätter“ hatten einfach keinen Bezug zum sozialistischen Realismus. Claus kam ursprünglich vom geschriebenen Wort her, wobei er den Textbegriff ganz weit fasste. Er beschriftete und bezeichnete transparente Papiere beidseitig so dicht und komplex, dass die Lesbarkeit der Schrift ausgelöscht wurde und das Lineament umschlug zum Bild. Zu einem weitgehend abstrakten Bild, das hin und wieder eine verbal lesbare Passage aufweist, das Assoziationen von Landschaftsräumen oder Physiognomien ermöglicht. Und vor allem: ein Bild, das nicht unveränderlich ist, sondern quasi selbst ein Prozess, ein Dialog ist aus Schriftfragmenten und Zeichenspuren zwischen Vorder- und Rückseite. Diese „Sprachblätter“ sind kein fertiges Objekt, sondern müssen vom Rezipienten lesend und betrachtend erschlossen, enträtselt, komplettiert werden. Insofern waren sie das Gegenteil vom sozialistischen Staatsrealismus mit seinem Wahrheitsanspruch.

LR: Grafische Kunstwerke aus der DDR genießen heute eine hohe und allgemeine Wertschätzung. Sie entstanden abseits der offiziellen, vom Staat beauftragten Großkunst in hoher Qualität und Dichte. Ist Carlfriedrich Claus als Grafiker nicht doch auch ein typischer Vertreter dieses Milieus?

BM: Ja und Nein. Pauschal betrachtet ist das hohe Niveau der DDR-Druckgrafik augenfällig. Die kleinen Formate taugten weniger für ideologische Themen, boten sich eher an für formales Experiment und künstlerische Innovation. Vielleicht entstanden deshalb im Sektor der Grafik landauf landab frische, unverbrauchte Blätter von hoher technischer und handwerklicher Brillanz. Ja, es stimmt, dass Carlfriedrich Claus von diesem fruchtbaren Umfeld inspiriert wurde. Als er sich um 1970 der Druckgrafik zuwandte, konnte er auf die drucktechnische Erfahrung von Künstlerfreunden wir Max Uhlig oder Thomas Ranft zurückgreifen, die ihm die Lithografien und Radierungen druckten. Speziell Thomas Ranft war Carlfriedrich Claus beim Druck der Aurora-Mappe (von der sich ein Exemplar ja im Bestand des MoMA befindet) äußerst hilfreich.

Andererseits sind die Druckgrafiken von Claus stilistisch, methodisch und auch von der intellektuellen Durchdringung her so singulär, dass sie sich dem Vergleich mit anderen, durchaus anspruchsvollen Druckgrafiken aus der DDR weitgehend entziehen.

LR: Wenn Carlfriedrich Claus nicht aus dem Kontext der DDR-Kunst zu erklären ist, wohin gibt es dann Bezüge? Zu Dada oder zu Paul Klee? Zur Mail Art?

BM: Dada besaß für Carlfriedrich Claus, besonders in jungen Jahren, eine enorme Strahlkraft. Dada war unangepasst und aufmüpfig, es war intermedial, und es war – was in den Jahren nach dem 2. Weltkrieg eine hohe Relevanz hatte – durch keine Kollaboration mit dem Nationalsozialismus beschmutzt. Mit Raoul Hausmann hatte Carlfriedrich Claus einen äußerst lebendigen, anregenden Briefwechsel – allerdings nur im Kalenderjahr 1960, weil es dann zum Zerwürfnis kam. Hausmann war verbittert und kompliziert.

Paul Klee war in der unabhängigen Kulturszene so etwas wie ein Säulenheiliger: unerreichbar fern (wer kannte schon Originale) aber hoch verehrt. So viele Klee- Bewunderer pro Kopf, wie es unter den kritischen Geistern in der DDR gab, finden sich vielleicht nicht oft [lacht]. Claus hat sich lebenslang, und zwar intensiv und analytisch, mit Klee beschäftigt. Anlässlich der ersten umfangreichen Klee- Ausstellung der DDR, die 1985 in den Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Dresden gezeigt wurde, hat er einen wunderbaren Text über sein Verhältnis zu diesem Künstler verfasst.

Verallgemeinernd kann ich sagen, dass die Kunst der historischen Avantgarden in den 1950er und frühen 1960er Jahren für Claus beispielgebend war, ohne dass er deshalb stilistisch in dieser Nachfolge gearbeitet hätte. Aber die formale Radikalität, die Kompromisslosigkeit und die Utopiehaltigkeit dieser Kunst faszinierten ihn – wie viele seiner Generationsgenossen in Ost und West auch. Künstlerisch vernetzt war Claus mit Vertretern der konkreten und visuellen Poesie. Unter diesen war die theoretische Durchdringung des künstlerischen Schaffensprozesses verbreitet. Und auch dem Arbeitsstil von Claus entsprach die Verschriftlichung des Diskurses. In diesen Zirkeln stellte er also aus, publizierte in deren Periodika. Zwangsläufig ergaben sich daher auch Überschneidungen hin zu Fluxus oder zur Mail Art.

LR: Hat Carlfriedrich Claus auf Künstlerkollegen Einfluss ausgeübt bzw. hat er bis heute – auf die aktuellen Strömungen – irgendwie Einfluss?

BM: Als sich in den 1970er Jahren die restriktive Kulturpolitik der DDR lockerte, entwickelte sich im damaligen Karl-Marx-Stadt (dem heutigen Chemnitz) eine lebendige, unangepasste und kreative Kunstszene. 1977 bemühten sich Michael Morgner, Thomas Ranft, Dagmar Ranft-Schinke und Gregor Torsten Schade/später Kozik um eine Zusammenarbeit mit Carlfriedrich Claus. Sie konnten ihn für eine Mitgliedschaft in der Künstlergruppe CLARA MOSCH gewinnen, die bis 1982 bestand und mit Ausstellungen, Land-Art-Projekten und prozessorientierten Kunstformen weit überregional Anerkennung fand. Claus war ein Außenseiter auch in dieser Gruppe – aber von allen wurde er als spiritus rector anerkannt.

Mehr indirekt, aber nachhaltig hat er auf junge Künstler gewirkt, die sich auf die DDR überhaupt nicht mehr einließen, sondern unbekümmert und uneingeschränkt eigenen Intentionen folgten. Olaf Nicolai beispielsweise sieht in Claus einen der ganz wenigen Anreger für konzeptionell künstlerisches Arbeiten. Die Freiheit und die Internationalität von Claus beeindrucken ihn ebenso wie die Intermedialität und Komplexität seines Werks oder die selbstverständliche Verbindung von Theorie und Kunst.