Cara Manes participated in MoMA’s C-MAP Asia group research trip to India and Bangladesh in January 2018. Of the many new and elucidating experiences she had while abroad, she found her time spent looking at Sheela Gowda’s work and speaking with the artist about her complex, multidisciplinary practice to be particularly instructive. Below is an account of these endeavors.

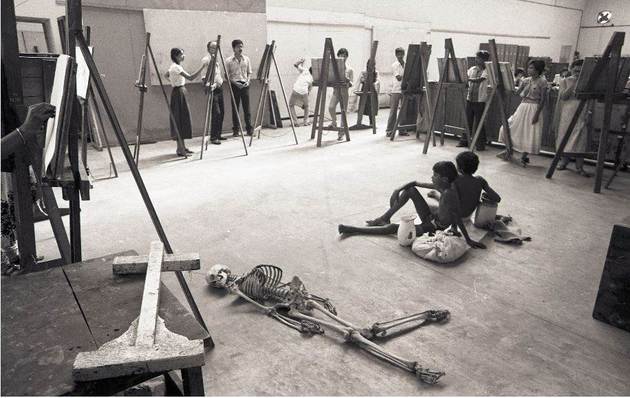

As part of MoMA’s C-MAP Asia group, I have had the distinct fortune of being able to make several trips to South Asia. Each time, I’ve visited new places and met new people, and each experience has bolstered my understanding of the history of modern art in the region, and has provided opportunities for engaging with its vibrant contemporary art community, as well. A few years ago, I visited the Faculty of Fine Arts at The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, an important art school whose curriculum, drawing on aspects of the German Bauhaus principles unifying art, craft, and design, encouraged students to look to traditional idioms, indigenous materials, and historical genres in an effort to define a genuinely new and Indian art.

It was in this context that I came to know the work of Sheela Gowda, an artist best known for making large-scale abstract sculptural installations. Born in 1957 in the Karnataka region of southern India, where she currently lives and works in its capital city, Bangalore, Gowda received a MA in painting from the Royal College of Art, London, in 1986, after studying in Baroda, and also at an equally historically important institution in Santiniketan. Though Gowda was trained as a painter, it was her interest in the specific medium of cow dung that prompted a shift in her work from two to three dimensions. Considered sacred in Hindu scripture, dung is formed into patties, often by village women laborers, and burned for fuel or applied to walls of Indian homes to protect their inhabitants. Ubiquitous in the Indian domestic landscape, the cow dung pats proved to be an ideal medium for Gowda to incorporate into her work: abstract, natural, available, and, most importantly, charged with reference—to culture, to place, to politics, and to personal history.

Gowda then began to seek other symbolically potent materials. She found them in the likes of empty tar drums (repurposed as road workers’ temporary housing), human hair, incense ash, red kumkum powder made from ground tumeric (all used in religious rituals), and, in the case of of all people—a work I saw at GALLERYSKE in Bangalore, my first stop on my trip—the remains of torn-down houses. Scavenged from the streets or purchased from scrapyard salesmen, these window frames, pillars, and doorjambs form the spine of of all people. Gowda painted the wooden fragments the bright yellows, pinks, and turquoises typical of Karnataka homes, and recombined them into structures that stand freely, lean, or stretch skyward; by doing so, she resuscitated them not to their original state but to their original integrity. Strewn on and among these reconstituted domestic fragments are thousands of small wood votive figurines that are typically distributed as gifts and kept in the homes of their recipients for good luck. Nearly abstract but for three small slits that signify a face, these figurines animate Gowda’s imagined architectural setting. With of all people, Gowda conjures a real place by stitching together elements from it, and also hints at a narrative with the figurative elements within it, all while maintaining a resolutely abstract visual language. In this way she constructs a complex environment that synthesizes the history, culture, and politics of her native India, western modes of twentieth-century abstraction, and her own biography.

Gowda has been the subject of several monographic presentations, most recently Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, UK (2017), and the Van Abbe Museum, Eindhoven (2013). She has an upcoming solo presentation at Hangar Bicocca, Milan in 2019. Her work has also been presented in international group exhibitions well over the past decade, including the Dhaka Art Summit (2017), biennials in Busan (2012), Sharjah (2009), and Venice (2009), and Documenta 12 (2007). She was a finalist for the Huge Boss Prize at the Guggenheim Museum (2014) and is represented by works in its and the Walker Art Museum’s collections. MoMA was fortunate enough to acquire of all people this spring, signaling an important investment on behalf of the Museum in tracing the significant developments in contemporary Indian art.

After viewing of all people in Bangalore, I was able to see another new installation by Gowda, this time at the Dhaka Art Summit in Bangladesh. This was my second visit to the Summit, an international research and exhibition biennale for art and architecture founded by the Samdani Art Foundation in 2012 and organized by the Foundation’s curator, Diana Campbell Betancourt. The Summit provides a crucial platform for exploring the history and development of South Asia’s cultural communities, bringing together artists, curators, academics, and interested visitors from around the globe to participate in a series of cross-disciplinary discussions and exhibitions. One of these such presentations was A Beast, a god, and a line, organized by Cosmin Costinas, Director of the arts organization Para-Site in Hong Kong. According to the attendant didactic materials, the exhibition considered the South Asian region of “Bengal’s position at the core of different geographical networks, reflecting the circulation of people and ideas in different historical times… [T]he exhibition unfolds in several chapters, positioning the material histories of textiles as a central thread that carries the trace of these exchanges.”

It was in this context that Gowda was commissioned to make a site specific installation. Discreetly sited under a back staircase in the Shilpakala Academy, a state-sponsored cultural center and the Summit’s main venue, Of Becoming¸ her contribution to the Summit, comprises dozens of “gamchas”—brightly colored cotton cloths used across South Asia as towels or worn by laborers as loincloths or head wraps—which are tied together and suspended in the space. These ubiquitous, everyday materials become the formal building blocks of an abstract sculptural installation, but one that is imbued with a specific political and cultural meaning.

The remainder of my trip brought me to a host of new places and experiences, including memorable visits to several renowned architectural sites, made all the more meaningful on account of my traveling companions, curators and research fellows in MoMA’s Department of Architecture and Design: the Faculty of Fine Arts in Dhaka, an art school designed by renowned Bangladeshi architect Muzharul Islam in 1948 which serves as an incubator for a new generation of contemporary artists; Auroville, an experimental utopian community in southern India founded in 1968 by the spiritual leader Mirra Alfassa and designed by visionary architect Roger Anger; and Le Corbusier’s masterful Court Complex in the northern city of Chandigarh, among other sites.

I ended my trip in Delhi, where I was lucky enough to make several studio visits, visit the India Art Fair with contemporary curator, scholar, and friend Gayatri Sinha, and see the marvelous career retrospective exhibition of artist Vivan Sundaram at the Kiran Nadar Museum. I have been aware of Sundaram’s multidisciplinary practice for some time now, but had not understood what a phenomenal painter he is! The exhibition teemed with remarkable, never-before-seen paintings from early in his career, such as Indeterminacy, 1967, which demonstrates the artist’s interest in Pop art, or, as his friend, artist Gulammohammed Sheikh described it, a “love of the mundane, the trivial and the trite, even kitsch.”