Alfred H. Barr, Jr., future director of The Museum of Modern Art, made a trip to Russia in 1927-28 to investigate the avant-garde, meeting with several Vkhutemas faculty while he was there. The Vkhutemas school in Moscow has often been termed the “Soviet Bauhaus” due to its temporal and pedagogical proximity to its more famous German counterpoint. In this essay, a close consideration of archival material from Barr’s trip help contextualize how such associations have come to overshadow Vkhutemas’s original contributions in art and architecture. A vitrine exhibition in the MoMA Library— BAUHAUS VKhUTEMAS: Intersecting Parallels, on view through October 26, 2018—features many of the materials discussed below.

“There is no living library that does not harbor a number of booklike creations from fringe areas. . . . some people become attached to leaflets and prospectuses, others to handwriting facsimiles or typewritten copies of unobtainable books; and certainly periodicals can form the prismatic fringes of a library.” —Walter Benjamin1Walter Benjamin, “Unpacking My Library,” in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), 66.

In 1927, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., the American art historian who would become the founding director of The Museum of Modern Art, embarked on an extensive European trip. Taking a break from teaching art history at Wellesley College, the twenty-five-year-old Barr saw this tour as an opportunity to study contemporary European culture and, on a more practical level, to collect bibliographic and visual material for his courses on modern art.2Sybil Gordon Kantor, Alfred H. Barr, Jr. and the Intellectual Origins of the Museum of Modern Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002), 146. A major destination was the Bauhaus in Dessau, where Barr met with the school’s director and architect Walter Gropius, as well as its faculty, including the painter Paul Klee, and the photographer, typographer, and painter László Moholy-Nagy.

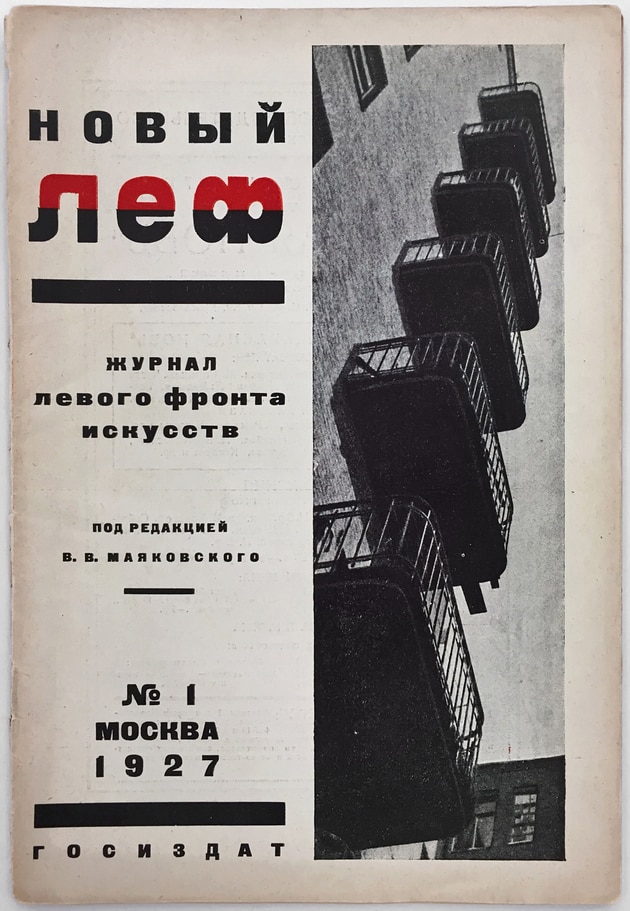

Barr was accompanied by Jere Abbott, a friend and fellow art history graduate from Harvard, who would become MoMA’s first associate director. While still in Germany, near the end of 1927, the two travelers decided to make an unplanned detour to Russia to witness firsthand its post-revolutionary avant-garde. Initially planning to spend two or three weeks in Moscow, they ended up staying and traveling across Russia for a month and a half.3Margaret Scolari Barr and Jere Abbott, foreword to “Russian Diary 1927–28,” October 7, Soviet Revolutionary Culture (Winter 1978): 8. Anxious to preserve the information they gathered, both Barr and Abbott kept lively diaries of the plays they watched, the people they met, and the things they learned.4Alfred H. Barr, Jr., “Russian Diary 1927–28,” Alfred H. Barr, Jr. Papers (AHB), IV.B.143, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York; the original is held in Harvard University’s Houghton Library, Cambridge, MA. Barr’s diary was published in full as Alfred H. Barr, Jr., “Russian Diary 1927–28,” October 7, Soviet Revolutionary Culture (Winter 1978): 10–51. Excerpts from Abbott’s diary were initially published as Jere Abbott, “Notes from a Soviet Diary,” Hound & Horn 2, no. 3 (April–June 1929): 257–66; and Hound & Horn 2, no. 4 (July–September 1929): 388–97. Abbott’s diary was published in full as Jere Abbott, “Russian Diary, 1927–28,” October 145 (Summer 2013): 125–223.

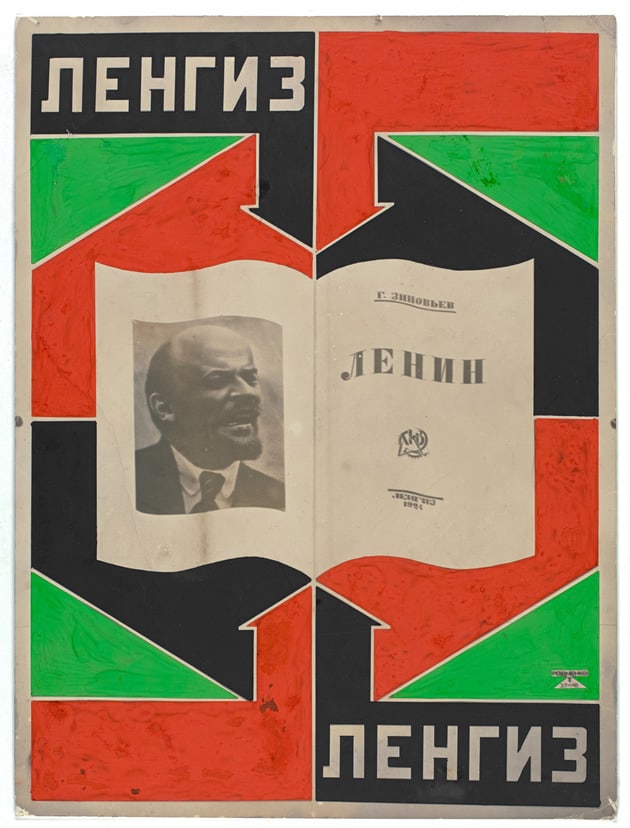

Having recently visited the Bauhaus in Dessau, Barr was especially keen to see VKhUTEMAS (also spelled Vkhutemas), an acronym for the Vysshie khudozhestvenno-tekhnicheskie masterskie (Higher state artistic and technical studios), in Moscow. In recent press and bibliography, the school is often reductively referred to as the “Soviet Bauhaus.”5See, for example, the review of a recent VKhUTEMAS exhibition at the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin: Agata Pyzik, “The ‘Soviet Bauhaus,’” Architectural Review 237, no. 1119 (May 2015): 110–11. However, Vkhutemas faculty comprised some of the most pioneering Soviet artists of the time, including Aleksandr Rodchenko, Varvara Stepanova, El Lissitzky, Vladimir Tatlin, and Gustav Klutsis, to name but a handful.6For a general overview of the protagonists and pedagogical approach of the school with an emphasis on architecture, see Anna Bokov, “VKhUTEMAS Training,” in Fair Enough: Pavilion of the Russian Federation at the 14th International Architecture Exhibition (Venice: La Biennale di Venezia, 2014), 100¬–11. Barr visited the Vkhutemas three times in January 1928. He actively sought to meet with faculty there to learn about their artistic practice and pedagogical activities, and to inform his own teaching of modern art back in the United States. Yet, his attempts were decisively hindered by language, as he did not know Russian.

Moreover, the most important obstacle for Barr in decoding the school and its pedagogy was its lack of printed matter: “The whole institution seemed painfully lacking in organization and equipment but the fine spirit of enthusiasm will conquer these technical difficulties with time and money. It was annoying, though, not to find any printed matter about the school, not even a list of professors or courses.”7Barr, “Russian Diary 1927–28,” 33. AHB, IV.B.143. Unlike the Bauhaus—whose posters, brochures, postcards, and books were crossing borders around the world—Vkhutemas and its workings remained largely unknown in European circles, let alone North American ones.8As Daria Sorokina points out in a recent comparison on the continuing obscurity of VKhUTEMAS, “As partial answer to the question of why the Bauhaus is known throughout the world while VKhUTEMAS is not, consider the Bauhaus’ achievements in publishing.” Daria Sorokina, “Bauhaus VKhUTEMAS: The History of Two Legendary Schools,” Readymag, https://stories.readymag.com/bauhaus-vkhutemas/.

Faced with an impregnable fortress, Barr found a new mission in obsessively amassing as much printed material directly or indirectly related to Vkhutemas, its faculty, and its students as he could get his hands on. The disproportionate number of personal papers accumulated during his stay in Moscow betray an impassioned collector of Russian printed matter, characterized by what Walter Benjamin calls “the thrill of acquisition.”9Walter Benjamin, “Unpacking My Library,” 60. For Benjamin, who in 1926 had also felt frustrated spending a winter in Moscow, the most memorable items are acquired “on trips, as a transient.”10Ibid., 63. Similarly for Barr, each piece of paper he gathered had its own story, promising to offer another small piece to the frustrating puzzle of the development of modern Russian art he felt unable to trace.

Barr’s and Abbott’s diaries from their Russian trip reveal their constant urge to compare and measure Vkhutemas against the Bauhaus. As Barr wrote about the Russian faculty of the former: “They were much interested in the Bauhaus and have evidently learned much from it. I asked [painter, critic, and administrator David] Sterenberg what were the chief differences between the two. He replied that the Bauhaus aimed to develop the individual whereas the Moscow workshops worked for the development of the masses. This seemed superficial and doctrinaire since the real work at the Bauhaus seems as social, the spirit as communistic as in the Moscow school.”11Barr, “Russian Diary 1927–28,” 33. AHB, IV.B.143. The Bauhaus is the only lens through which they seemed able to interpret the Vkhutemas, a riddling entity often understood as simply derivative.

Delving into Barr’s Russian trip library reveals an impressive variety and volume of material, amounting to more than sixty archival folders. In connecting the dots between Barr’s and Abbott’s diary entries and the dozens of items they brought back from their reconnaissance trip east, the seeming “disorder” of the archive begins to make sense. Every newspaper clipping, postcard, pamphlet, bulletin, travel guide, journal, exhibition catalogue and book reveals a brief moment of contact, a personal story, a rare glimpse into not only the faculty of Vkhutemas, but also the school’s “intersecting parallels” with the Bauhaus.12This oxymoron refers to the subtitle of the exhibition organized by Meghan Forbes and the author, on the occasion of which this essay was written: BAUHAUS↔VKhUTEMAS: Intersecting Parallels, The Museum of Modern Art Library, New York, September 25–October 26, 2018.

NOTE

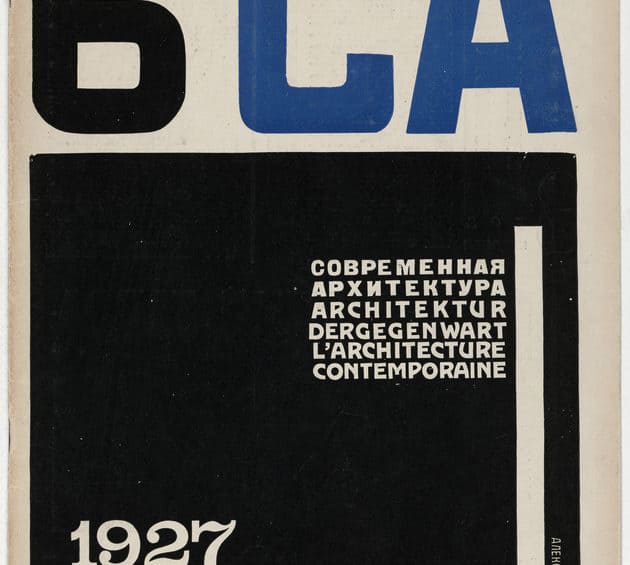

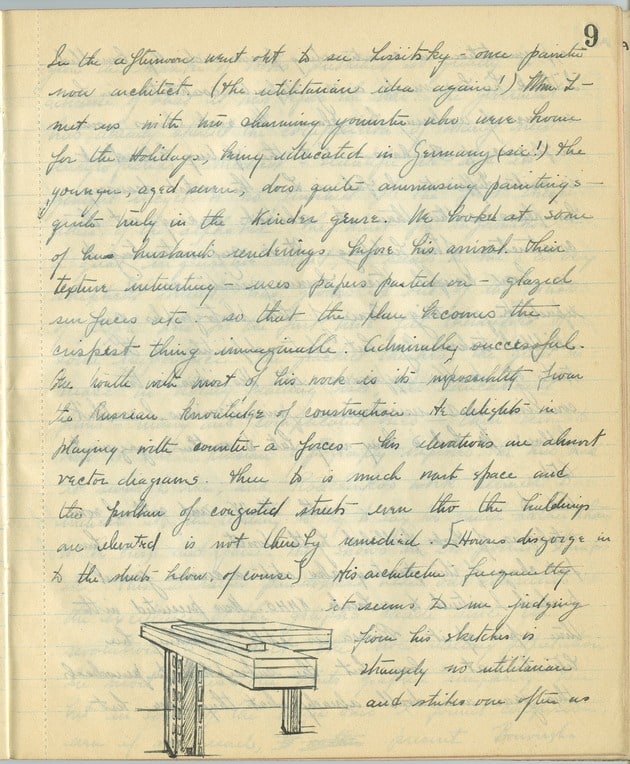

On January 3, 1928, Barr met with the architect, artist, designer, and typographer El Lissitzky, who taught architecture, interiors, and furniture design at Vkhutemas. Barr carried printed matter from the Bauhaus to Vkhutemas, and he delivered a handwritten personal note from Gropius to Lissitzky, entrusted to him a few weeks earlier in Dessau. Judging from the positive way in which the gesture was received, Barr assumed that Lissitzky “is evidently very friendly with the Bauhaus.”13Ibid. He reflected on Lissitzky’s “quite ingenious” book designs and photos, which he noted in his diary were, nonetheless, suggestive of Moholy-Nagy’s work at the Bauhaus.14Ibid. In 1927, the Vkhutemas had published one of its most important book-length publications, which, showcasing the work of the architecture faculty, features a cover designed by Lissitzky.15N. Dokuchaev and P. Novitskii, eds., Arkhitektura: raboty arkhitekturnogo fakul’teta VKhUTEMASa [Architecture: Works of the architecture faculty of VKhUTEMAS], 1920–1927 (Moscow: Izdanie VKhUTEMASa, 1927), cover. Strangely enough, there is no evidence that a copy of it was shown or made available to Barr.

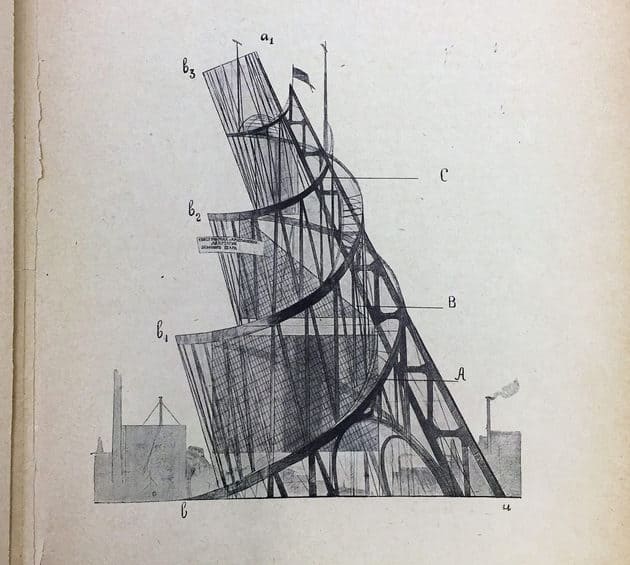

SKETCH

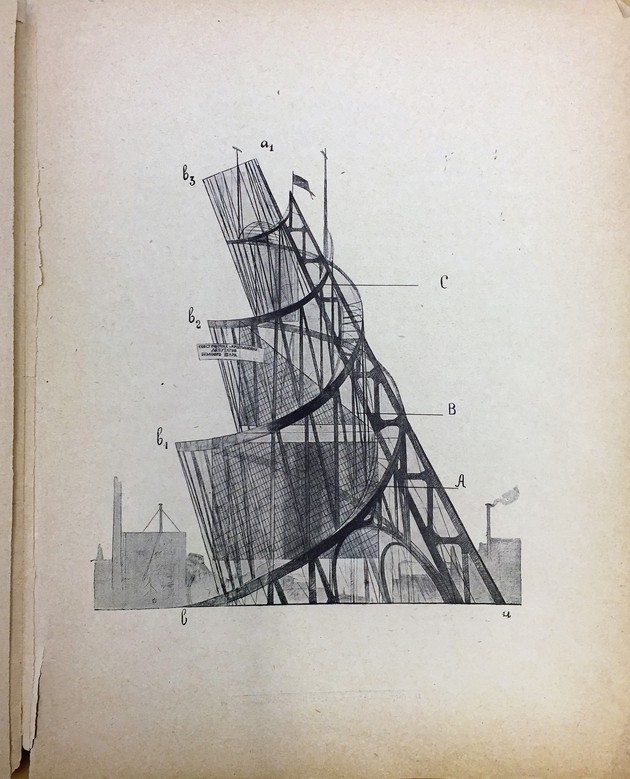

Lissitkzy must have also shown Barr and Abbott his audacious design forWolkenbügel (Cloud Iron), a network of “horizontal skyscrapers” positioned at major intersections across Moscow. Barr was quick to consider the proposition as “the most frankly paper architecture I have ever seen.”16Barr, “Russian Diary 1927–28,” 15. AHB, IV.B.143. Abbott, on the other hand, rehearsed Lissitkzy’s paper architecture by sketching a perspective view of the daring cantilevered design under his diary entry for that day, and he noted that Lissitzky’s “work shows some influence of Bauhaus—but the feeling behind it is quite different . . . It is very interesting to see how careful these former painters are to repudiate painting.”17Jere Abbott, “Russian Diary, 1927–28,” October 145 (Summer 2013): 158. A few days later, Abbott concluded that “Lissitzky gets many ideas from [the] Bauhaus but he is not a copyist.”18Ibid., 206.

“JUNK”

The afternoon of the same day, Barr and Abbott met with Aleksandr Rodchenko, who taught furniture design at Vkhutemas, and Varvara Stepanova, his “talented wife,” at their apartment.19Barr, “Russian Diary 1927–28,” 16. AHB, IV.B.143. Language was an obstacle once again, as these “brilliant, versatile artists” only spoke Russian.20Ibid. As early as 1921, both Stepanova and Rodchenko had abandoned painting in order to fully devote themselves to photography, advertising, and textile design. A seemingly unsatisfied Barr insisted on looking at their older abstract paintings, which he was surprised to find “preceding the earliest geometrical things I’ve seen.”21Ibid, 15. While impressed with their masterful photographs, Barr was determined to “find some painters if possible.”22Ibid, 16. Recalling the incident from a different angle, Stepanova wrote: “Those Americans came to call: one of them dull, dry, and bespectacled—Professor Alfred Barr. . . . is interested only in art—painting, drawing. He turned our whole apartment upside down. They made us show them all kinds of old junk. Toward the end Barr got all hot and bothered.”23Varvara Stepanova, Chelovek ne mozhet zhit’ bez chuda. Pis’ma, poeticheskie opyty, zapiski khudozhnitsy [A person cannot live without a miracle. Letters, poetry experiments, notes of the artist], ed. O. V. Mel’nikov, compiled by V. Rodchenko and A. Lavrent’ev (Moscow: Izd. “Sfera,” 1994), 222; cited in Magdalena Dabrowski, Leah Dickerman, and Peter Galassi, eds., Aleksandr Rodchenko (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1998), 140.

For Stepanova, Barr’s uptight character and inquiries were indicative of an academic who seemed stuck in a bygone idea of fine art and nonmechanical media: “I am absolutely not interested in this anymore . . . the soul is already filled with photography.”24Anna Savitskaya, “Alfred Barr Made Us Pull Out All the Old Junk,” Art Newspaper, November 25, 2014, https://perma.cc/SM22-L6AR.

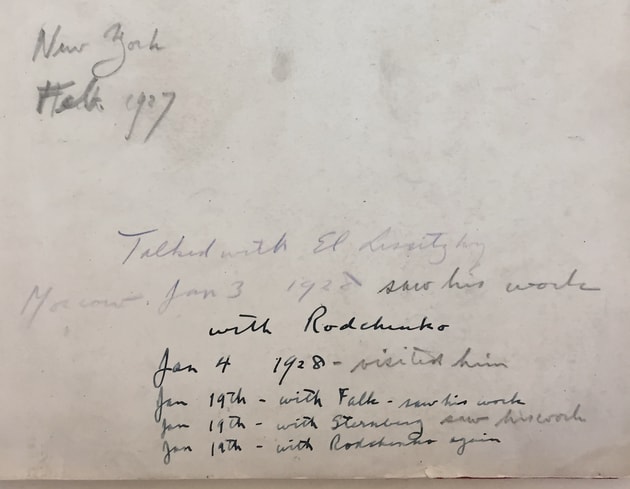

TEXTBOOK

On January 19, 1928, Barr reconvened with Rodchenko, this time at the latter’s Vkhutemas workshop. Barr arrived loaded with questions, many of them regarding Rodchenko’s formative years as a painter, which the artist answered “in a rather disgruntled manner, insisting that the past bored him utterly and that he couldn’t remember at all when he had painted this way or that.”25Barr, “Russian Diary 1927–28,” 33. AHB IV.B.143. Stepanova apparently answered on behalf of her husband, for she later chronicled in her diary: “Barr showed us a book on Russian art, in English, by [Louis] Lozowick. Everything was accurate—even the parts on the Constructivists—and there was a list of all their names. There’s an entire chapter on Rodchenko. Barr made us check it for accuracy . . . There turned out to be only one error: that Rodchenko had been a student of Malevich. This was pointed out to Barr, and the passage was underlined.”26Stepanova, Chelovek ne mozhet zhit’ bez chuda, 222; cited in Dabrowski, Dickerman, and Galassi, Aleksandr Rodchenko, 140.

The book, the accuracy of which Rodchenko and Stepanova were interrogated about, was Modern Russian Art.27Louis Lozowick, Modern Russian Art (New York: Société anonyme, 1925). AHB, IX.B.14, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. Written by the Russian-born émigré artist Louis

Lozowick and published by the Société anonyme in New York in 1925, it was one of the very few English sources on modern Russian art of the twenties in circulation in the United States.28Elizabeth Jones, “A Note on Barr’s Contribution to the Scholarship of Soviet Art,” October 7, Soviet Revolutionary Culture (Winter 1978): 54. Barr was apparently so attached to it that he had taken his copy all the way across the Atlantic and then carried it through Europe all the way to Moscow, where he wrote down within it the dates on which he met with Russian artists and architects, all of whom appeared to be faculty members at Vkhutemas. For the far-flung art historian, these close encounters presented a rare opportunity not only to witness a foreign artistic scene but also, in the absence of an established bibliography, to fact-check the few existing accounts of its hitherto genealogy.

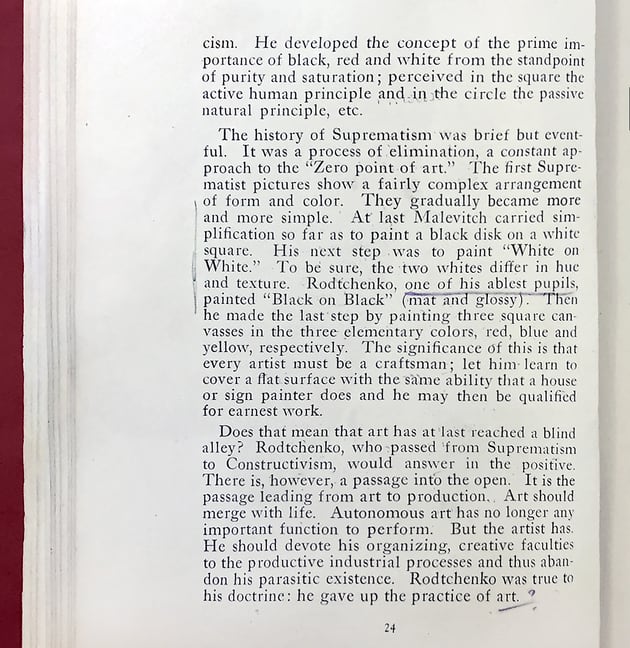

PHOTO

During another visit to Vkhutemas, on January 19, 1928, Rodchenko again welcomed Barr to his workshop. It is possible that it was on this very day that the artist gave Barr a gelatin silver print of one of his photographs that captures the snowy courtyard of Vkhutemas as seen from above on a sunny winter day. It is likely that Rodchenko had taken this picture from a balcony situated off his workshop at the Vkhutemas building on 21 Myasnitskaya Street, a site that served as a laboratory for his architectural photography. Rodchenko’s gift, later added to the MoMA collection as Barr’s gift, is part of his iconic series of sharp-angle shots depicting the school building’s balconies and service access ladders. One of these photographs also appears on the cover the first issue of Novyi lef (New left), a journal also designed by Rodchenko, a copy of which Barr made sure to bring back to North America.29Aleksandr Rodchenko, Novyi lef. Zhurnal levogo fronta iskusstv, no. 1 (1927). AHB, IX, B.103. Novyi lef [New left] was the second Journal of the Left Front of the Arts. Its first issues were edited by poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, and the entire run was designed by Rodchenko.

PAMPHLET

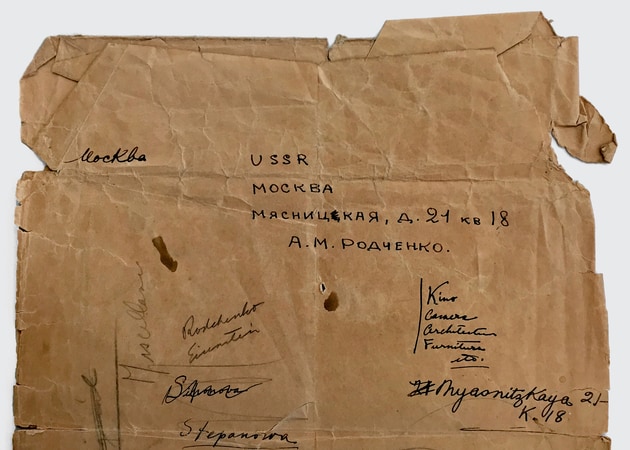

Rodchenko’s photographic gift may have (briefly) transcended the language barrier with Barr, who attempted to scribble the former’s address at Vkhutemas in Cyrillic, along with other notes about Russian artists and publications in Latin script, on a yellow envelope.30Envelope annotated in Barr’s handwriting. AHB, IX.B.100. The same could not be said about Tatlin, who was introduced to Barr at Vkhutemas on the same day. Tatlin had recently been appointed head of the school’s metal workshop and spoke with Barr in broken German. Barr was intrigued by the “very beautiful metal constructions” produced by Tatlin’s students, but he left empty-handed. Three days later, Barr was delighted to meet Russian modern art critic Nikolai Punin, who provided him with “a copy of his excellent monograph on Tatlin,” and possibly also his famous 1920 pamphlet on Tatlin’sPamiatnik III Internatsionala (Monument to the Third International), which would resurface a couple more times in Barr’s personal papers.31Barr, “Russian Diary 1927–28,” 52. AHB IV.B.143; Nikolai Punin, Pamiatnik III Internatsionala Monument to theThird International. AHB IX.B.106.

JOURNAL

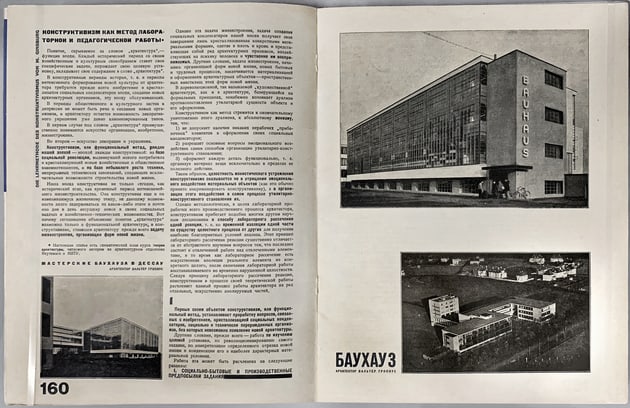

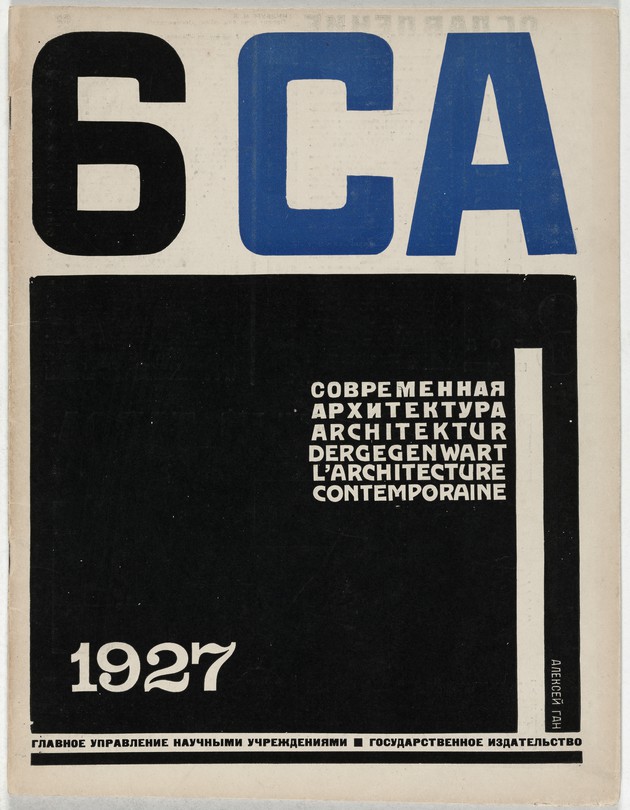

A few days before departing, on January 26, 1928, Barr also met with Moisei Ginzburg, a “brilliant, young architect” who taught at Vkhutemas.32Barr, “Russian Diary 1927–28,” 43. AHB, IV.B.143. Ginzburg was a founding member of the Organization of Contemporary Architects (OSA) and a coeditor of the widely circulated architectural journal SA. Sovremennaia arkhitektura (CA. Contemporary Architecture). An illustrated article by Ginzburg on “constructivism as [a] method of laboratory and pedagogical work,” published a few months earlier in SA, is included, along with Walter Gropius’s design for the new Bauhaus building in Dessau and photographs by Lucia Moholy, among others. The appearance of the Bauhaus and its faculty on the pages of SA are testament not only to OSA’s admiration of the Bauhaus’s mission but also to the aspiration of many Vkhutemas architecture faculty members to engage in a critical dialogue with the German school’s faculty and ideas through publications, exhibitions, and even mutual exchanges of students.33Christina Lodder, “The VKhUTEMAS and the Bauhaus,” in The Avant-Garde Frontier: Russia Meets the West, 1910–1930, eds. Gail Harrison Roman and Virginia Hagelstein Marquardt (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1992), 196–234, esp. 213–214, 218, 234n128.

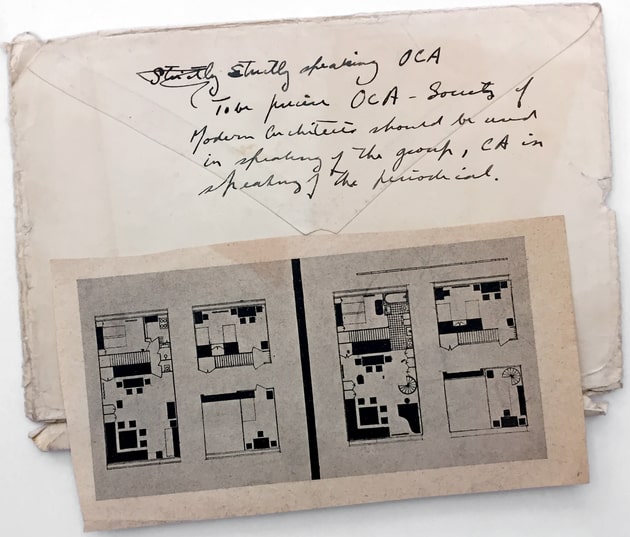

CLIPPING

Ginzburg offered back issues of SA to Barr, who wrote in his diary of Ginzburg’s “excellent maquette for a workers’ apartment house and club.”34M. Ia. Ginzburg, “Kommunal’nyi dom A 1” [Communal house A 1], SA. Sovremennaia arkhitektura, no. 4–5 (1927): 130–31. A few months after returning to the United States, Barr contributed an article titled “Notes on Russian Architecture” to the journal The Arts.35Alfred H. Barr, Jr., “Notes on Russian Architecture,” The Arts 15 (February 1929), 103–106. AHB, V.B.44, Folder 5. There, his initial appraisal of Ginzburg’s design is revised to question the project as “perhaps . . . influenced by Gropius’ building for the Deutsches Bauhaus at Dessau.”36Ibid., 105. Barr’s papers include a clipping from SA with plans for the project, which he kept in a white envelope annotated with explanations about the OSA and SA acronyms, most possibly to illustrate his article. His original reaction is self-censored, and the clipping remained unused. As former MoMA curator and Barr’s collaborator Elizabeth Jones later noted, “Architecture as practiced by the pioneers of modernism in the West provided a standard against which to judge the recent buildings in Moscow.”Jones, “A Note on Barr’s Contribution to the Scholarship of Soviet Art,” 53-54.

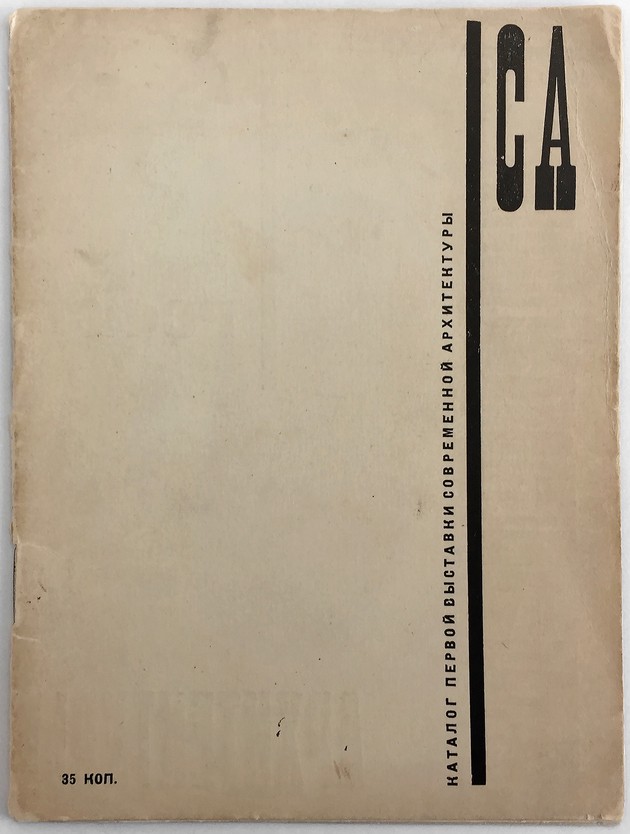

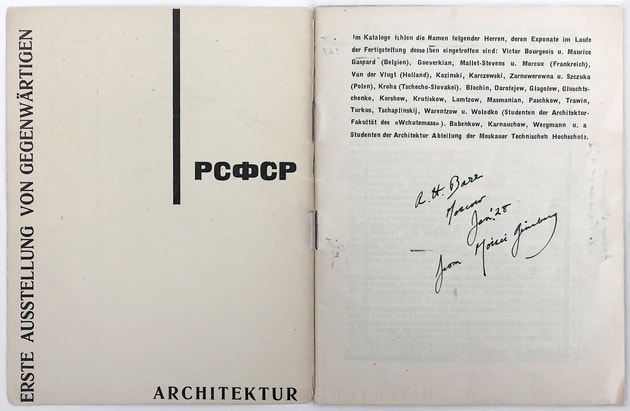

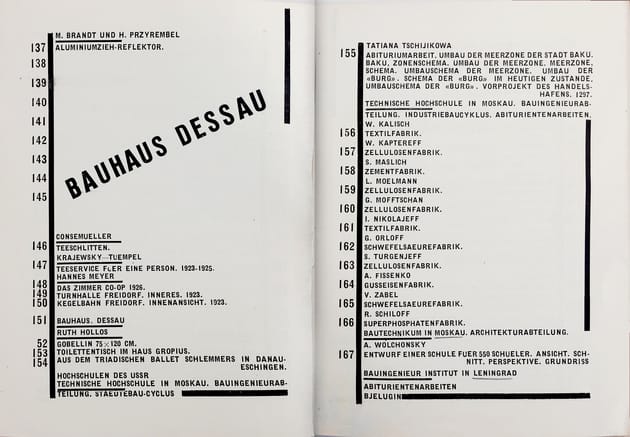

CATALOGUE

Perhaps the rarest item included in Barr’s Russian trip papers is one of the five thousand copies printed of the catalogue for the First Exhibition of Contemporary Architecture, which he obtained “from Moisei Ginzburg.”37SA: Katalog pervoi vystavki sovremennoi arkhitektury = SA: Erste Ausstellung von gegenwärtigen architektur CA: First Exhibition of Contemporary Architecture, AHB, IX.B.4. Barr’s handwriting on the opening spread of the catalogue reads: “A. H. Barr Moscow Jan. ’28 from Moisei Ginzburg.” Typeset in both Russian and German, this publication was designed by the artist and designer Aleksei Gan, one of the main theoreticians of Constructivism. Held inside the Vkhutemas building in the summer of 1927, the exhibition was organized by members of OSA and brought together works by Vkhutemas and Bauhaus students and faculty under one roof.38Lodder, “The VKhUTEMAS and the Bauhaus,” 213. The exhibition was divided into six sections, one of which was exclusively devoted to the Bauhaus and featured the work of Herbert Bayer, Marianne Brandt, Erich Consemüller, Ruth Hollos, Max Krajewski, Wolfgang Tümpel, Hannes Meyer, and Walter Gropius, among others. For a comprehensive overview of the exhibition and a full English translation of its catalogue, see: K. Paul Zygas, “OSA’s 1927 Exhibition of Contemporary Architecture: Russia and the West Meet in Moscow” in The Avant-Garde Frontier: Russia Meets the West, 1910–1930, 102–42. Even though the exhibition had closed a few months before his arrival, Barr made use of his copy of the catalogue to take notes on Moscow’s architects and buildings, many of which he later referenced in his “Notes on Russian Architecture.”

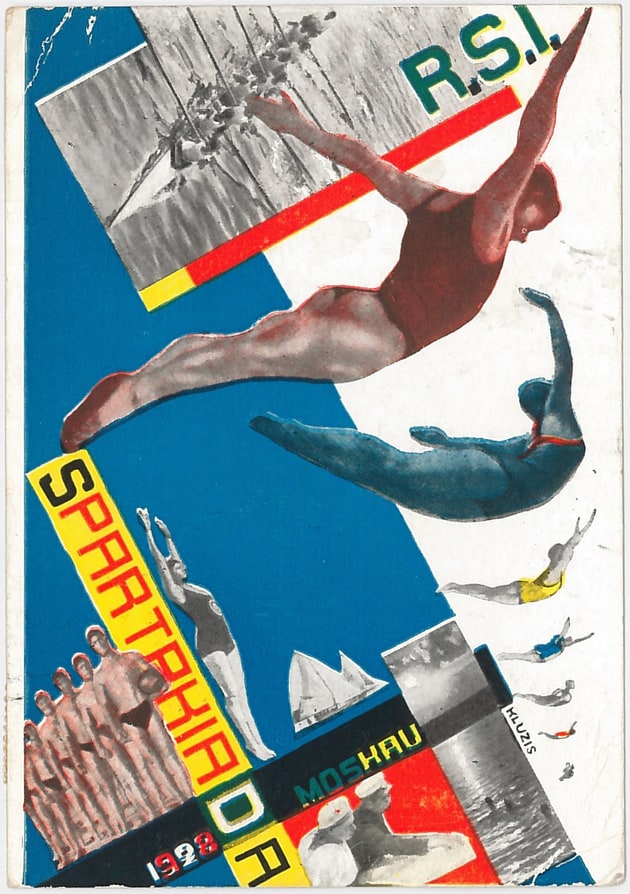

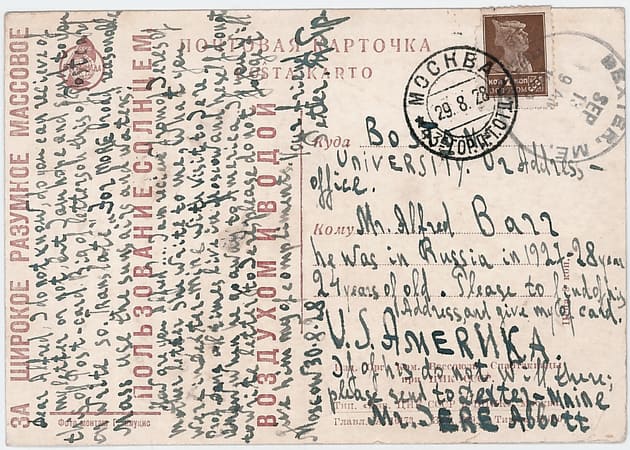

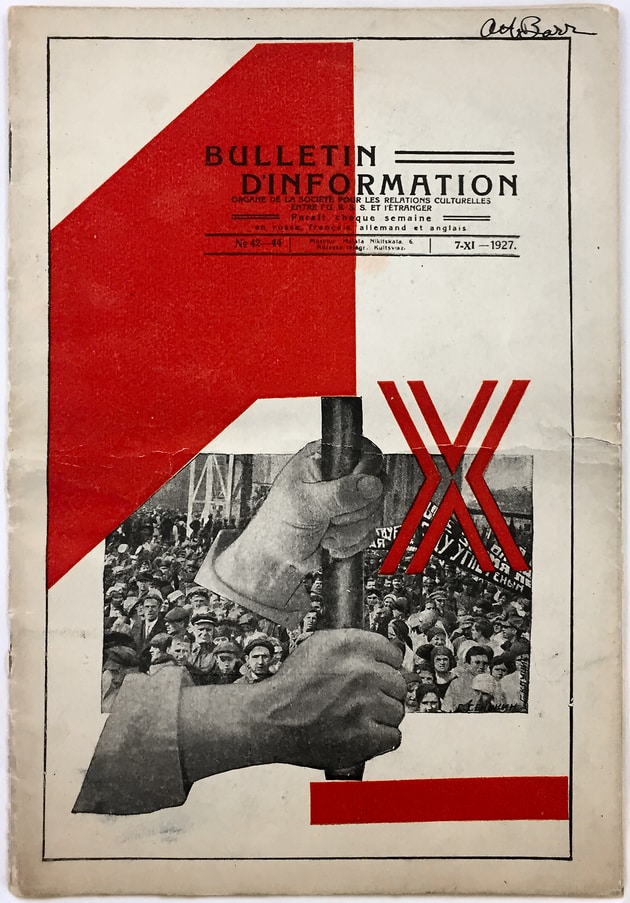

POSTCARD

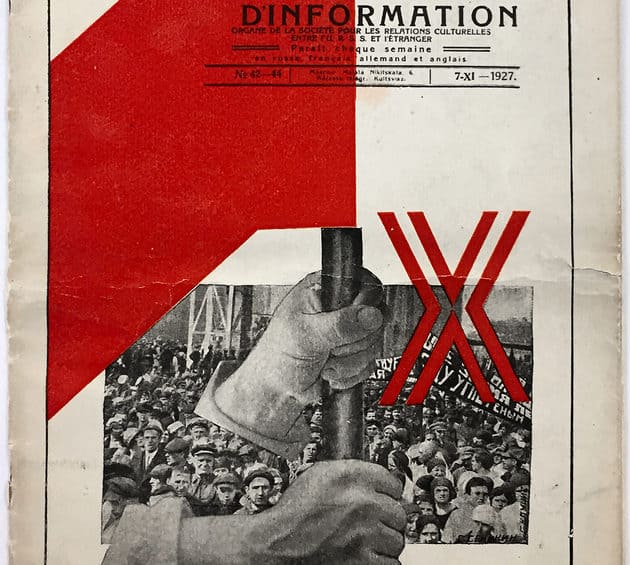

Barr’s paper trail on modern Russian art continued to grow even after his return to the United States. One of the items sent to him from Moscow, in August 1928, was a postcard that, for the All-Union Spartakiada Sporting Event of 1928, was designed by Gustav Klutsis.39Petr Likhachev to Alfred Barr, Moscow, August 30, 1928. AHB, IX.B.154, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. Klutsis, who initially studied with Malevich and graduated from Vkhutemas in 1921, taught color in the wood and metal workshop of the school from 1924 until 1930.40Lodder, Russian Constructivism, 246. Barr must have already been familiar with his work as Klutsis had codesigned the cover of a 1927 issue of the Bulletin d’information, the weekly news bulletin of VOKS (Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries), which Barr had brought back in his suitcase from Moscow.41Bulletin d’information. Organe de la Société pour les Relations Culturelles Entre l’U.R.S.S. et l’Étranger 7–XI, no. 42–44 (1927). AHB, IX.B.35. However, this postcard was not sent by Klutsis or any other Vkhutemas faculty, but rather by Petr Likhachev, a nineteen-year-old interpreter who had spent enough time assisting Barr and Abbott in Moscow to distinguish Barr’s curiosity for any portable piece of paper on modern Russian art and design. Likhachev’s choice to send a postcard designed by a Vkhutemas faculty member thus can be read as deliberate gesture to contribute to his American friend’s towering collection of ephemera related to modern Russian art and architecture.

Throughout the Russian trip of 1927–28, Barr struggled to comprehend both the Vkhutemas faculty he met and any distinctive qualities of the school vis-à-vis its overshadowing sibling, the Bauhaus. Vkhutemas might have been less successful in the dissemination of its ideas and image through the circulation of printed media (let alone commercial products), but at the same time, its distinct place in the history of the twentieth-century avant-garde and its far-reaching impact through the education of literally thousands of Russian and Soviet students cannot be overestimated. Despite initially interpreting Vkhutemas as chaotic and derivative of the Bauhaus, as missing the “organizing genius” of Gropius, Barr gradually drew a more nuanced comparison, noting: “The important difference so far as I could discern lay in the fact that the aim of the Moscow school was more practical, its technique far less efficient; the aim of the Bauhaus more theoretical, its technique much superior. But with men such as Lissitzky and Tatlin and [painter and teacher Robert] Falk there is much in the future.”42Barr, “Russian Diary 1927–28,” 33. AHB, IV.B.143.

In the years immediately following his trip to Russia, Barr established regular correspondence with members of the intellectual circles he had met in the fields of art, architecture, theater, and cinema, and he wrote numerous articles, published both in the United States and Russia, summarizing his evolving observations on both historical and contemporary Russian culture.43Alfred H. Barr, Jr., “Za grantsei: Ruki” [Abroad: Hands], Sovetskoe kino 1 (1928): 26–27; “The ‘LEF’ and Soviet Art,” Transition, no. 14 (Fall 1928): 267–70; “The Researches of Eisenstein,” Drawing and Design 4 (June 1928): 155–56; “Sergei Michailovich Eisenstein,” The Arts 14 (December 1928), 316–21; “Russian Icons,” The Arts 17 (February 1931).

In later years, Barr claimed that the medium-specific structure of the Bauhaus workshops played a key role in conceptualizing his strategic proposal for MoMA’s media-specific, multi-departmental structure.44Alfred H. Barr, Jr. to George Rowley, May 20, 1949; cited in Kantor, Alfred H. Barr, Jr. and the Intellectual Origins of the Museum of Modern Art, 155. However, as he himself was first to point out in his Russian diary, a similar structure characterized Vkhutemas and included “painting, sculpture, architecture, printing (color and various processed), typography, graphic arts, furniture designing, advertising posters, and techniques of materials.”45Barr, “Russian Diary 1927–28,” 31. AHB, IV.B.143. During Barr’s directorship, works by Vkhutemas faculty—including Malevich, Lissitzky, Rodchenko, and Stepanova—entered MoMA’s collection for the first time (sometimes exported as “technical drawings” through Germany, or wrapped inside Barr’s umbrella to protect them from seizure by the Nazis).46Kantor, Alfred H. Barr, Jr. and the Intellectual Origins of the Museum of Modern Art, 183. His first few bumpy encounters with Rodchenko soon transformed into an exchange of letters, photographs, and ideas—and ultimately culminated in peaks, such as MoMA’s 1971 retrospective exhibition of Rodchenko’s work, to which Barr lent much of his own personal collection.47AHB, IX.B.97–105; David Vance to Alfred H. Barr, Jr., “Loan Receipt,” February 1, 1971. AHB, IX.B.103; Jennifer Licht to Alfred H. Barr, Jr., “Loans to Rodchenko Exhibition,” February 9, 1971. AHB, IX.B.101.

Unlike the Bauhaus, Vkhutemas as a pedagogical institution of global significance never made it into Barr’s infamous 1936 diagram interpreting the evolution of abstract art and cubism as a series of uncomplicated, one-way vectors that converge and diverge.48Juliet Koss, “The Pale Red Bauhaus and the USSR,” (symposium, Before and After 1933: The International Legacy of the Bauhaus, The Museum of Modern Art, NY, January 22, 2010); Anna Bokov, “Institutionalizing the Avant-Garde: VKhUTEMAS, 1920–1930” (lecture, Collins/Kaufmann Forum for Modern Architectural History, Columbia University, New York, NY, April 10, 2018). Neither did it receive the American exposure that Gropius’s school enjoyed through MoMA’s 1938–39 Bauhaus exhibition and (multiple reprints of) its accompanying catalogue.49Herbert Bayer, Walter Gropius, Ise Gropius (eds.), Bauhaus 1919–1928 (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1938; reprinted in 1955, 1972, 1975. Perhaps Barr’s contribution to shedding a light, albeit indirectly, on Vkhutemas might lie elsewhere, as his travels, ephemera collection, and writings did make available the ideas and artistic achievements of the Russian avant-garde for new audiences on the other side of the Atlantic. More than ninety years after Barr’s Russian trip, though, the continued Othering of the Vkhutemas does not only still hinder a rightful assessment of its original contributions in art and architecture, but also prevents us from considering its idiosyncratic, and only seemingly disordered pedagogical culture as an interpretation of modernity in its own right.

- 1Walter Benjamin, “Unpacking My Library,” in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), 66.

- 2Sybil Gordon Kantor, Alfred H. Barr, Jr. and the Intellectual Origins of the Museum of Modern Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002), 146.

- 3Margaret Scolari Barr and Jere Abbott, foreword to “Russian Diary 1927–28,” October 7, Soviet Revolutionary Culture (Winter 1978): 8.

- 4Alfred H. Barr, Jr., “Russian Diary 1927–28,” Alfred H. Barr, Jr. Papers (AHB), IV.B.143, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York; the original is held in Harvard University’s Houghton Library, Cambridge, MA. Barr’s diary was published in full as Alfred H. Barr, Jr., “Russian Diary 1927–28,” October 7, Soviet Revolutionary Culture (Winter 1978): 10–51. Excerpts from Abbott’s diary were initially published as Jere Abbott, “Notes from a Soviet Diary,” Hound & Horn 2, no. 3 (April–June 1929): 257–66; and Hound & Horn 2, no. 4 (July–September 1929): 388–97. Abbott’s diary was published in full as Jere Abbott, “Russian Diary, 1927–28,” October 145 (Summer 2013): 125–223.

- 5See, for example, the review of a recent VKhUTEMAS exhibition at the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin: Agata Pyzik, “The ‘Soviet Bauhaus,’” Architectural Review 237, no. 1119 (May 2015): 110–11.

- 6For a general overview of the protagonists and pedagogical approach of the school with an emphasis on architecture, see Anna Bokov, “VKhUTEMAS Training,” in Fair Enough: Pavilion of the Russian Federation at the 14th International Architecture Exhibition (Venice: La Biennale di Venezia, 2014), 100¬–11.

- 7Barr, “Russian Diary 1927–28,” 33. AHB, IV.B.143.

- 8As Daria Sorokina points out in a recent comparison on the continuing obscurity of VKhUTEMAS, “As partial answer to the question of why the Bauhaus is known throughout the world while VKhUTEMAS is not, consider the Bauhaus’ achievements in publishing.” Daria Sorokina, “Bauhaus VKhUTEMAS: The History of Two Legendary Schools,” Readymag, https://stories.readymag.com/bauhaus-vkhutemas/.

- 9Walter Benjamin, “Unpacking My Library,” 60.

- 10Ibid., 63.

- 11Barr, “Russian Diary 1927–28,” 33. AHB, IV.B.143.

- 12This oxymoron refers to the subtitle of the exhibition organized by Meghan Forbes and the author, on the occasion of which this essay was written: BAUHAUS↔VKhUTEMAS: Intersecting Parallels, The Museum of Modern Art Library, New York, September 25–October 26, 2018.

- 13Ibid.

- 14Ibid.

- 15N. Dokuchaev and P. Novitskii, eds., Arkhitektura: raboty arkhitekturnogo fakul’teta VKhUTEMASa [Architecture: Works of the architecture faculty of VKhUTEMAS], 1920–1927 (Moscow: Izdanie VKhUTEMASa, 1927), cover.

- 16Barr, “Russian Diary 1927–28,” 15. AHB, IV.B.143.

- 17Jere Abbott, “Russian Diary, 1927–28,” October 145 (Summer 2013): 158.

- 18Ibid., 206.

- 19Barr, “Russian Diary 1927–28,” 16. AHB, IV.B.143.

- 20Ibid.

- 21Ibid, 15.

- 22Ibid, 16.

- 23Varvara Stepanova, Chelovek ne mozhet zhit’ bez chuda. Pis’ma, poeticheskie opyty, zapiski khudozhnitsy [A person cannot live without a miracle. Letters, poetry experiments, notes of the artist], ed. O. V. Mel’nikov, compiled by V. Rodchenko and A. Lavrent’ev (Moscow: Izd. “Sfera,” 1994), 222; cited in Magdalena Dabrowski, Leah Dickerman, and Peter Galassi, eds., Aleksandr Rodchenko (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1998), 140.

- 24Anna Savitskaya, “Alfred Barr Made Us Pull Out All the Old Junk,” Art Newspaper, November 25, 2014, https://perma.cc/SM22-L6AR.

- 25Barr, “Russian Diary 1927–28,” 33. AHB IV.B.143.

- 26Stepanova, Chelovek ne mozhet zhit’ bez chuda, 222; cited in Dabrowski, Dickerman, and Galassi, Aleksandr Rodchenko, 140.

- 27Louis Lozowick, Modern Russian Art (New York: Société anonyme, 1925). AHB, IX.B.14, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.

- 28Elizabeth Jones, “A Note on Barr’s Contribution to the Scholarship of Soviet Art,” October 7, Soviet Revolutionary Culture (Winter 1978): 54.

- 29Aleksandr Rodchenko, Novyi lef. Zhurnal levogo fronta iskusstv, no. 1 (1927). AHB, IX, B.103. Novyi lef [New left] was the second Journal of the Left Front of the Arts. Its first issues were edited by poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, and the entire run was designed by Rodchenko.

- 30Envelope annotated in Barr’s handwriting. AHB, IX.B.100.

- 31Barr, “Russian Diary 1927–28,” 52. AHB IV.B.143; Nikolai Punin, Pamiatnik III Internatsionala Monument to theThird International. AHB IX.B.106.

- 32Barr, “Russian Diary 1927–28,” 43. AHB, IV.B.143.

- 33Christina Lodder, “The VKhUTEMAS and the Bauhaus,” in The Avant-Garde Frontier: Russia Meets the West, 1910–1930, eds. Gail Harrison Roman and Virginia Hagelstein Marquardt (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1992), 196–234, esp. 213–214, 218, 234n128.

- 34M. Ia. Ginzburg, “Kommunal’nyi dom A 1” [Communal house A 1], SA. Sovremennaia arkhitektura, no. 4–5 (1927): 130–31.

- 35Alfred H. Barr, Jr., “Notes on Russian Architecture,” The Arts 15 (February 1929), 103–106. AHB, V.B.44, Folder 5.

- 36Ibid., 105.

- 37SA: Katalog pervoi vystavki sovremennoi arkhitektury = SA: Erste Ausstellung von gegenwärtigen architektur CA: First Exhibition of Contemporary Architecture, AHB, IX.B.4. Barr’s handwriting on the opening spread of the catalogue reads: “A. H. Barr Moscow Jan. ’28 from Moisei Ginzburg.”

- 38Lodder, “The VKhUTEMAS and the Bauhaus,” 213. The exhibition was divided into six sections, one of which was exclusively devoted to the Bauhaus and featured the work of Herbert Bayer, Marianne Brandt, Erich Consemüller, Ruth Hollos, Max Krajewski, Wolfgang Tümpel, Hannes Meyer, and Walter Gropius, among others. For a comprehensive overview of the exhibition and a full English translation of its catalogue, see: K. Paul Zygas, “OSA’s 1927 Exhibition of Contemporary Architecture: Russia and the West Meet in Moscow” in The Avant-Garde Frontier: Russia Meets the West, 1910–1930, 102–42.

- 39Petr Likhachev to Alfred Barr, Moscow, August 30, 1928. AHB, IX.B.154, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.

- 40Lodder, Russian Constructivism, 246.

- 41Bulletin d’information. Organe de la Société pour les Relations Culturelles Entre l’U.R.S.S. et l’Étranger 7–XI, no. 42–44 (1927). AHB, IX.B.35.

- 42Barr, “Russian Diary 1927–28,” 33. AHB, IV.B.143.

- 43Alfred H. Barr, Jr., “Za grantsei: Ruki” [Abroad: Hands], Sovetskoe kino 1 (1928): 26–27; “The ‘LEF’ and Soviet Art,” Transition, no. 14 (Fall 1928): 267–70; “The Researches of Eisenstein,” Drawing and Design 4 (June 1928): 155–56; “Sergei Michailovich Eisenstein,” The Arts 14 (December 1928), 316–21; “Russian Icons,” The Arts 17 (February 1931).

- 44Alfred H. Barr, Jr. to George Rowley, May 20, 1949; cited in Kantor, Alfred H. Barr, Jr. and the Intellectual Origins of the Museum of Modern Art, 155.

- 45Barr, “Russian Diary 1927–28,” 31. AHB, IV.B.143.

- 46Kantor, Alfred H. Barr, Jr. and the Intellectual Origins of the Museum of Modern Art, 183.

- 47AHB, IX.B.97–105; David Vance to Alfred H. Barr, Jr., “Loan Receipt,” February 1, 1971. AHB, IX.B.103; Jennifer Licht to Alfred H. Barr, Jr., “Loans to Rodchenko Exhibition,” February 9, 1971. AHB, IX.B.101.

- 48Juliet Koss, “The Pale Red Bauhaus and the USSR,” (symposium, Before and After 1933: The International Legacy of the Bauhaus, The Museum of Modern Art, NY, January 22, 2010); Anna Bokov, “Institutionalizing the Avant-Garde: VKhUTEMAS, 1920–1930” (lecture, Collins/Kaufmann Forum for Modern Architectural History, Columbia University, New York, NY, April 10, 2018).

- 49Herbert Bayer, Walter Gropius, Ise Gropius (eds.), Bauhaus 1919–1928 (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1938; reprinted in 1955, 1972, 1975.