Lyn Hsieh reflects on education strategies she encountered during the C-MAP Asia research group’s trip to India and Bangladesh in January 2018. As department manager in the Education Department at MoMA, Hseih is interested in learning from the ways different institutions engage with audiences and structure educational programs. She cites the Children’s Art Carnival of 1962, which was organized by MoMA’s Education department and toured through cities in India, as an example of how relationships can be sustained.

At the generous invitation of C-MAP, I traveled to India and Bangladesh for the first time. I was impressed by the creative energy of the people and places I visited. Prior to my trip, I was aware of the fact that cultural institutions in India are structured differently from those in the United States. As someone who has worked in the Greater China area as well as in New York for the past decade, I am interested in how different museum systems shape their engagements with the public. For instance, I remember vividly how inspiring it was to see the distinctive and nimble education programs that my Taiwanese colleagues had created to respond to the lifestyles of their local audiences. On this particular research trip, I was curious to learn how Indians and Bangladeshis encounter the arts, as well as what the effective entry points are—that is, what entices people in these countries to visit museums.

During my two-week C-MAP trip, thanks to Prajna Desai and Sean Anderson, the leaders of the trip, I had the unique opportunity to visit a wide range of places: historical sites, modern architecture, artists’ studios, museums, galleries, art schools, and the Dhaka Art Summit. With the eventful itinerary and our leaders’ great knowledge of the local art scenes, I was able to observe how art is learned in diverse settings in both India and Bangladesh.

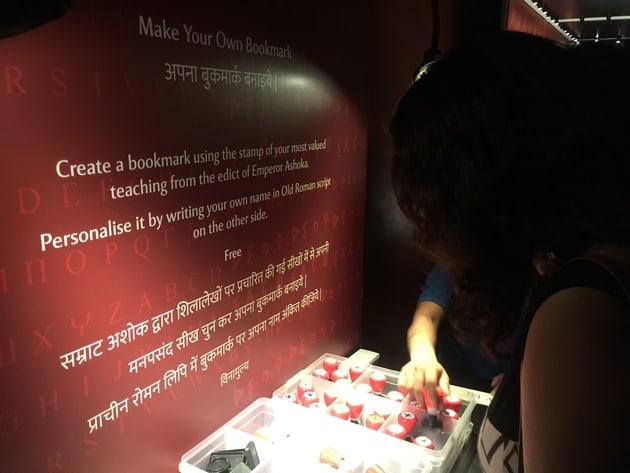

Based on my experience, it seems that institutions often introduce hands-on activities as part of visitors’ exhibition journeys. These in-gallery interventions create moments in which visitors are encouraged to pause and to reflect on the works on display. The activities are intuitive and compelling. Without needing much guidance, one can easily drop in, engage, and then leave at any given moment. The stamp station at CSMVS and the building stations at JKK are brilliant examples of how simple props can be used to illuminate an artist’s ideas and process, and to stimulate deep conversations and social learning among visitors.

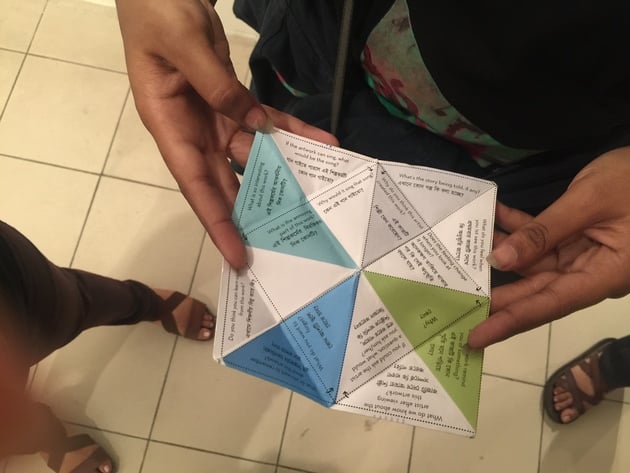

What I found fascinating is that these programs are playful and tailored to all ages. They are not limited to a specific audience. Instead, they speak to the core desire of all human beings: to express themselves. For instance, the paper fortune-telling game was very popular at the Dhaka Art Summit. The staff member had visitors play the game and answer the prop questions on each flap, such as “What is the annoying part of this work?”, “Why?”, ” What do you want to forget?” This game and the blindfolding game at the Dhaka Art Summit are refreshing ways to lead people to see details of artworks, and to guide them in articulating their feelings about their experience. The informality of these gamelike programs offers a comfortable environment in which participants and spectators may socialize and exchange ideas.

Seeing how accessible these programs are was an aha moment on this research trip. The realization struck me in several ways: first, it challenged the way we (at MoMA) divide our visitors, and then it made me think about how our framework could be opened up to more outside-the-box possibilities.

Since returning, I have been thinking about how to break the rules (in a good way) in my own work. For example, in my role as department manager in the Education Department, when reviewing budget proposals, I have started asking if it would be possible to scale programs up to attract a broader range of visitors. How can we design a coordinated workflow and structure that fosters cross-generational programs? With this one-size-fits-all mindset, the Education Department is experimenting with various cross-audience programs in order to shape a more welcoming experience for all visitors.

For example, this thinking has led us to transform the Explore This! Activity Stations from a family program to an all-ages programs. This program was originally conceived to engage family visitors with art-making in the galleries. After three months of prototyping, testing, and refining the program, through analyzing feedback from visitors, we realized the unfulfilled demand from adult visitors. They were eager to participate, but discouraged by the “Family Programs” title. We have since dropped ‘Families’ from the title in order to encourage participation by all visitors—not just those with children.

Additionally, this research trip has led to me to think about ways in which MoMA, an established institution with a full range of programs, can learn from institutions with completely different structures, and/or of different scales and social contexts. The discovery of a “secret sauce” often requires time and commitment. I wonder how I can transform the relationships built during this research trip into lasting dialogues. What unique collaborations could the Education Department develop with museums in India and Bangladesh? What would the impact on all participating museums be?

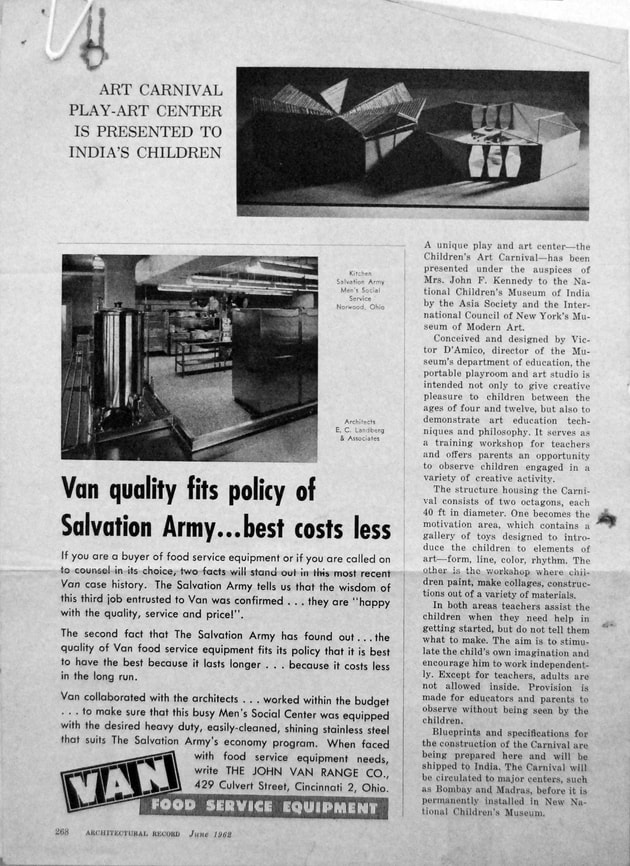

Luckily, my questions are answered in the beautiful history between MoMA and India—and the annual Children’s Art Carnival at the Museum (1942– 69) organized by Victor D’Amico, the founding director of MoMA’s Education Department. The Carnival, which consisted of imaginative spaces designed to engage children in art processes, became the symbol of a progressive democratic society. With support from the US government, it was a featured exhibit in the United States Pavilion at the Brussels World’s Fair in 1958. Indira Gandhi was so inspired by what she saw in Brussels that she invited first lady Jacqueline Kennedy to present MoMA’s Children’s Art Carnival to the National Children’s Museum in New Delhi in 1962. After its stay at New Delhi, the Carnival traveled to several Indian cities, including Hyderabad, Madras, Bangalore, and Ahmedabad. It was housed entirely within its own structure and then placed in “Bal Bhavan” (Bal Bhavans are national centers devoted to the creative development of children). When I visited National Bal Bhavan in New Delhi, I saw how the ideas behind the Children’s Art Carnival are still manifest, with tweaks to meet the local audience’s needs. Seeing how this telling history has unfolded over more than fifty years gives me confidence in exploring possible collaborations with our colleagues in India, Bangladesh, and beyond.