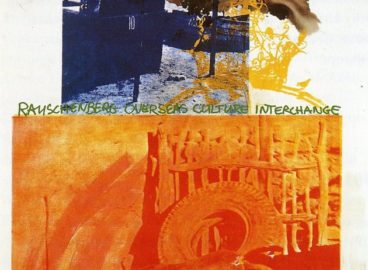

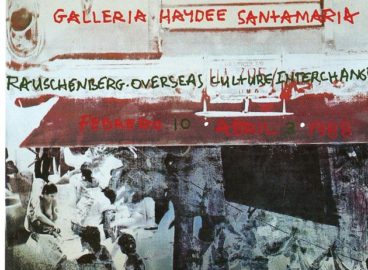

This essay considers Robert Rauschenberg’s 1975 residency in Ahmedabad, India, which fostered an environment of exchange and collaboration between Rauschenberg and the Sarabhai family. The visit inspired continuing projects that used art-making to forge relationships between cultural contexts, including an expansion of the Sarabhai family’s commitment to inviting American artists to India and the development of the Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange (ROCI). It discusses how the social and political valences of making work using local materials functioned in Rauschenberg’s practice during this period, as well as how this usage fits into a larger picture of increasingly globalized art production.

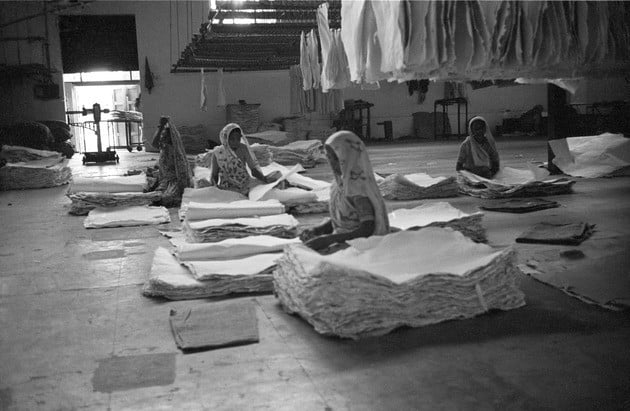

On May 18, 1975, Robert Rauschenberg arrived at “The Retreat,” the twenty-two-acre estate of the Sarabhai family, north of the old city of Ahmedabad. Anand Sarabhai extended an invitation to the artist to make work drawing upon the resources of a paper mill located at the nearby Gandhi Ashram (Sabarmati), dedicating both staff and machinery to assist the artist in the creation of what would become his Bones series (1975). The two men had maintained a correspondence for more than a decade, since Rauschenberg’s first visit to Ahmedabad while working as the costume and lighting designer for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s 1964 World Tour, which had visited Ahmedabad for two performances in the fall of that year.

Hiroko Ikegami has compellingly argued that Rauschenberg’s role as costume and lighting designer for Cunningham’s dance company, specifically his work during the World Tour, for which the artist “not only devised sets and costumes from materials collected in each locale but also enacted his own performances and created works of art, often involving collaboration with local art communities,” provided the genesis for the founding of the Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange (ROCI) in 1984.1Hiroko Ikegami, The Great Migrator: Robert Rauschenberg and the Global Rise of American Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010), 7. Yet the artist’s 1975 visit to India remains underexplored as a formative moment for this later initiative. Closer attention to Sarabhai family members’ roles as not only patrons, but also collaborators—conceptually and sometimes even literally—in the production of Rauschenberg’s work in India complicates the Orientalist implications of a Western artist who travels to South Asia for inspiration. The abstract Bones and Unions series Rauschenberg made while in Ahmedabad mark an evolution in the artist’s practice toward an international focus, where Rauschenberg’s use of scrap or discarded material became a method to explore the social and political valences of making work using local materials and processes within an increasingly globalized network of art production.

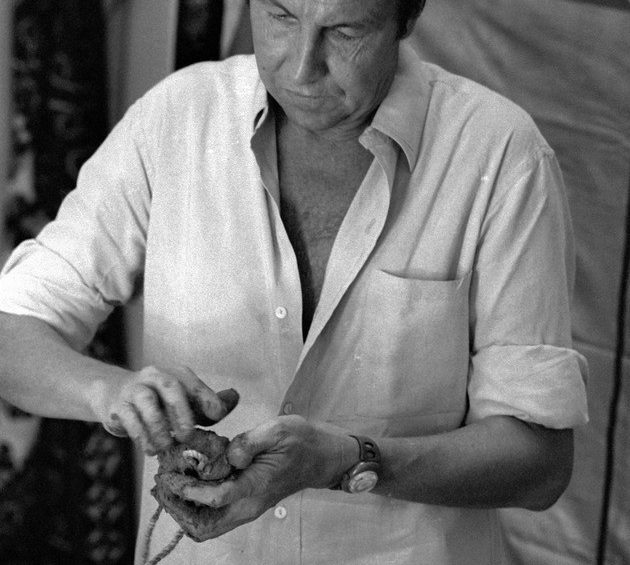

As would later become his practice when making work under the auspices of ROCI, Rauschenberg traveled with family, friends, and trusted collaborators. He invited a team from the Los Angeles–based printmaking studio Gemini G.E.L., who had assisted with the production of the artist’s self-portrait Booster, made at their Los Angeles studio in 1967, as well as the Pages (1974) and Fuses (1974) series made in collaboration with Gemini founder Ken Tyler at the Paper Mill Richard de Bas in Ambert, France. Rauschenberg’s trip to India was modeled on this previous collaboration, and Anand extended the invitation when he found out from the artist that planning difficulties had made a previously conceived collaboration with Gemini at a paper mill in Japan untenable. The contingent from Gemini included Sidney Felsen, his wife Rosamund and their daughter Suzanne; as well as the printmaker Charles Ritt; Bob Petersen, the artist’s partner, who had also trained as a printmaker at Gemini; and Christopher Rauschenberg, the artist’s son, who joined the group to help oversee production at the paper mill. Also traveling with Rauschenberg were the photographer Gianfranco Gorgoni and Rauschenberg’s studio assistant Hisachika Takahashi.

Rauschenberg was not the first American to visit the The Retreat. Gira Sarabhai, an architect who trained with Frank Lloyd Wright, had extended an invitation to Alexander Calder in 1954, which led to a three-week residency where the artist constructed a series of mobiles inspired by his experience. Another invitation was extended to Isamu Noguchi to visit the estate in 1958. Asha Sarabhai recalls how Rauschenberg’s visit inspired Anand to create a more formal artist residency, a mutually beneficial “exchange system” where the Sarabhais supported the creation of work by international artists and received gifts from their visitors, which allowed them to build up an impressive collection, a task that would have been largely impossible without the residency, due to stringent foreign exchange regulations at the time.2“The Reminiscences of Asha and Suhrid Sarabhai,” interview with Asha Sarabhai conducted by Cameron Vanderscoff and Gina Guy on March 18, 2015. Robert Rauschenberg Oral History Project. Columbia Center for Oral History Research, Columbia University in the City of New York and Robert Rauschenberg Archives. http://www.rauschenbergfoundation.org/Artist/oral-history/asha-and-suhrid-sarabhai, 21. At Rauschenberg’s recommendation, a number of artists affiliated with the American neo-avant-garde, including Frank Stella, Robert Morris, and Lynda Benglis visited India. The architecture of The Retreat itself was also an example of such patronage; the Villa Sarabhai, which became the family’s main residence, was designed by Le Corbusier, who had been commissioned by Jawaharlal Nehru to design the master plan for the new capital city of Chandigarh. Gita Sarabhai’s ongoing correspondence with John Cage, who she met in New York when she was referred to him as a potential student in the 1940s, led to an invitation to the Merce Cunningham Dance Company to perform in Ahmedabad, which was realized in 1964. Suhrid and Asha Sarabhai also developed their own friendships with John Cage and David Tudor while at Cambridge University in 1959, where Suhrid remembers a visit from Cage and Tudor after Cage won a Volkswagen minibus in a German television competition. This vehicle would become the main mode of transportation for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s 1964 World Tour.3Ibid., 79.

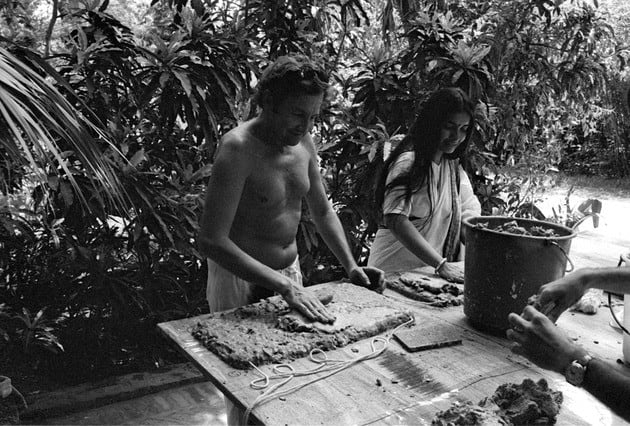

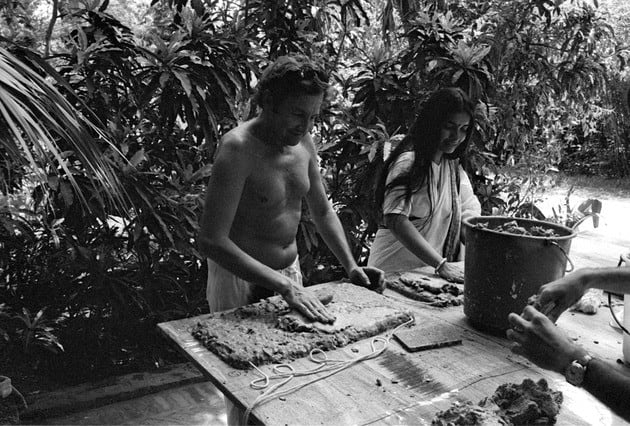

While in Ahmedabad, the Cunningham Company performed at Sheth Mangaldas Town Hall on the evenings of October 21 and 22. They were invited by Mrinalini Sarabhai and her husband Vikram to visit and rehearse at the Darpana Academy of Performing Arts, founded by the couple in 1949. At the performances, Suhrid recalls that, in addition to performing works from Cunningham’s repertory, “[Mrinalini Sarabhai] and Merce Cunningham then improvised and had a dance piece together as well at that time.”4Ibid., 82. Cunningham and Mrinalini developed a lasting friendship, and he provided an introduction for her 1985 dance text, Creations. Suhrid’s recollection of the improvised dance as a model for a responsive, mutual creative exchange became the model for Rauschenberg’s visit. The Unions, which Rauschenberg made in the Sarabhai’s garden, were formed with “rag-mud” mixed with tamarind seeds and fenugreek and then dried by the intense heat of the summer sun. Making “rag-mud” became a communal affair with assistance not only from his own team, but also the Sarabhai family and their staff. Asha describes how the garden and buildings within the compound influenced Rauschenberg’s choice of material for the series, in which she recognizes an allusion to the traditional mud huts of Ahmedabad:

[A] lot of buildings and homes were built with a combination of cow dung, straw, and earth, and then tamarind seed as something to strengthen it. And then very thick walls were built up, which are great insulation as well because they keep cool in the summer and warm in the winter. I think Bob had seen—[Manorama] Mani, my mother-in-law, had had one of these houses, a small one, a hut built in the garden. So that was there. Then they were occasionally embellished with mirror work and seeds and all sorts of things from whatever you find around you . . . So I think the sense of earth being used as something else was also part of the sort of visual environment that probably Bob encountered.5Ibid., 27.

Asha reflects on how the production of this work within the space of the Sarabhai’s home manifested not only in “unions” between the individuals involved, but also in the way that the meaning accrued through the material itself: “For me, it was really that removal from the museums into a domestic space, if that makes any sense, that I love about it. Ever since then, one has—I don’t know, you sense it or feel it in all of Bob’s work, that he’s—it’s what it happens to be. I think it’s a bit like what I was saying about the potential of things, that they both inhere in themselves, but they also inhere in being able to become something so much more than just that material. And that I loved.”6Ibid., 47.

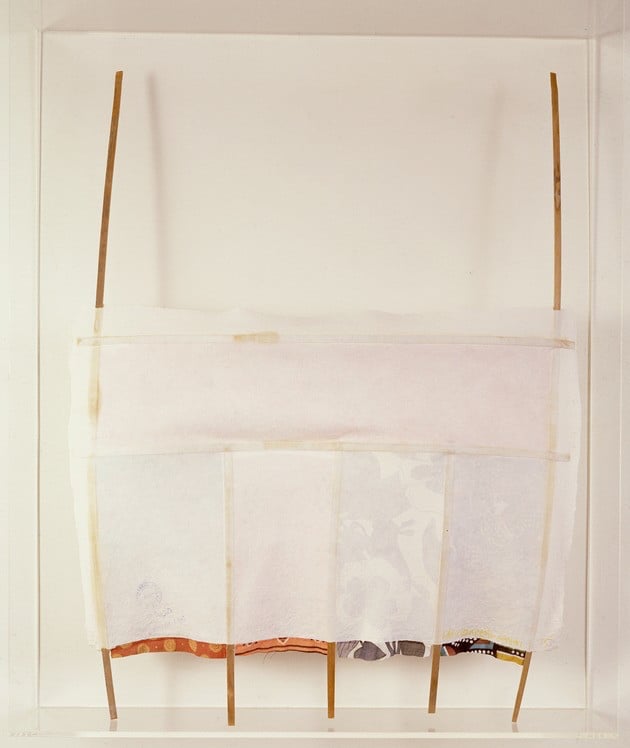

In the Bones and Unions series, khadi fabric functions as both formal inspiration and a method for rooting this work within the social and political values of the Indian independence movement. Rauschenberg was fascinated by the material, amassing a large collection over the course of his stay. Sidney Felsen recollects being particularly struck by how Capitol (a Union) appears when activated, creating a juxtaposition of texture and color through the contrast of mud and fabric: “[I]n the center is a square cut and behind it is a piece of fabric, a beautiful piece of fabric. And it’s on a rolling trolley, so to speak, and then as you move this piece of fabric by the pole it’s on, the image in the square changes its color.”7“The Reminiscences of Sidney Felsen,” interview conducted by James McElhinney on November 9, 2013, and December 13, 2013. Robert Rauschenberg Oral History Project. Columbia Center for Oral History Research, Columbia University in the City of New York and Robert Rauschenberg Archives, http://www.rauschenbergfoundation.org/artist/oral-history/sidney-felsen, 116. In contrast, Asha Sarabhai connects the domestic life of the estate with the social and political implications of the khadi fabrics: “Daily life at the estate, including the weekly arrival of fabric vendors [. . .] the fabrics that we went out and looked for were the khadi ones, which were the handspun and the handwoven, and they were the second-hand ones that were found in these piles where people were selling them.”8“The Reminiscences of Asha and Suhrid Sarabhai,” 41. She draws a connection to the political implications of the fabric and its use as a manifestation of Mahatma Gandhi’s teachings lauding local hand production in order to reduce reliance on imported goods.

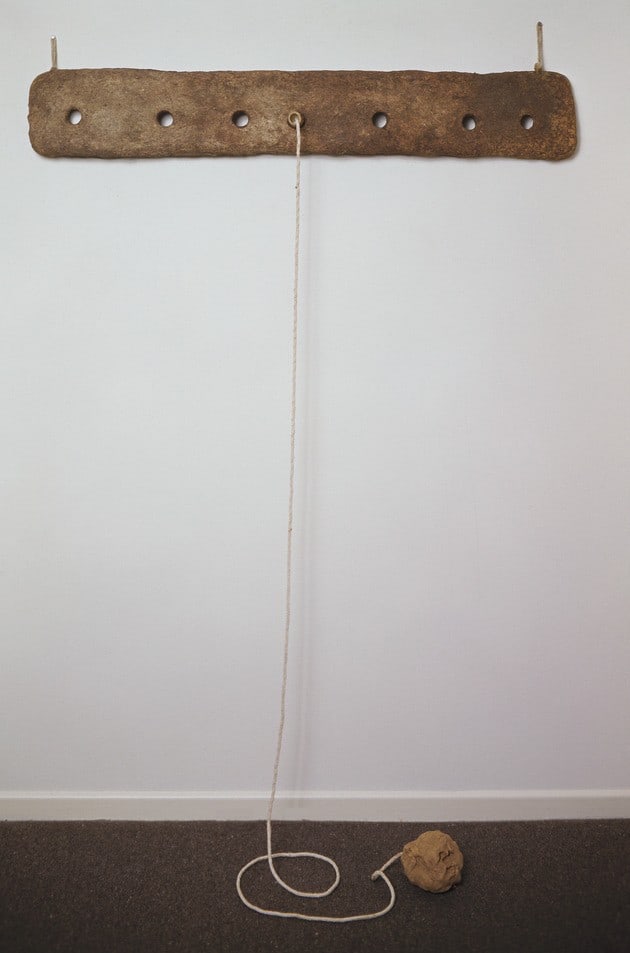

The political and social significance of the material components of the series Rauschenberg made in India is made more explicit in the production of the Bones series, overseen by Christopher Rauschenberg, Rosamund Felsen, and Bob Petersen, with assistance from the workers at the paper mill located near the Gandhi Ashram. Bamboo and scraps of fabric were incorporated into handmade molds that were then filled with paper pulp, creating a “rag-paper” assemblage that joined found material, an ancient process of papermaking, and labor from the mill founded in response to Gandhi’s teachings in order to provide employment for people who would otherwise be destitute. These works, along with the Jammers (1975), which Rauschenberg made from khadi fabric in the fall of 1975 after returning to his studio in Captiva, Florida, are often praised for their beauty and sparse composition. Since these works are abstract, the significatory power of the materials from which they are constructed and the context of the environment in which they were made is often evacuated from the conversations about their meaning, effecting an erasure of their sociopolitical content.

For both the Sarabhai family and Robert Rauschenberg, the artist’s 1975 visit to Ahmedabad inspired continuing projects using art-making to forge relationships between cultural contexts. The Sarabhais developed a robust artist residency, creating a dialogue with American artists that continued for decades and lead to exhibitions of the work created at The Retreat in both American and Indian institutions. Rauschenberg became more explicit in his project using artistic expression to promote human rights in an international context, eventually founding the ROCI program in 1984. The potential political significance of local material became a hallmark of ROCI, under which Rauschenberg and his team made art inspired by the countries they visited on trips to China, Tibet, Cuba, and the USSR, among other locations. The Ahmedabad visit marks a moment when collaborative vision—a uniting of form and function—inspired a new model of partnership and relationship-building within a global artistic network.

Bibliography

Ikegami, Hiroko. The Great Migrator: Robert Rauschenberg and the Global Rise of American Art. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013.

Keefe, Alexander, and David Anfam. Jammers. London: Gagosian Gallery, 2013. Exhibition catalogue.

Calder’s Voyage to India: Important Works from a Private Collection. Christie’s, 2016. http://www.christies.com/zmags?ZmagsPublishID=102550e3. Auction Catalogue.

“Made in India.” Press Release. The Museum of Modern Art, October 1985. https://www.moma.org/documents/momapress-release332945.pdf.

“The Reminiscences of Asha and Suhrid Sarabhai,” interview with Asha Sarabhai conducted by Cameron Vanderscoff and Gina Guy on March 18, 2015. Robert Rauschenberg Oral History Project. Columbia Center for Oral History Research, Columbia University in the City of New York and Robert Rauschenberg Archives. http://www.rauschenbergfoundation.org/Artist/oral-history/asha-and-suhrid-sarabhai.

“The Reminiscences of Sidney Felsen,” interview conducted by James McElhinney on November 9, 2013, and December 13, 2013. Robert Rauschenberg Oral History Project. Columbia Center for Oral History Research, Columbia University in the City of New York and Robert Rauschenberg Archives. http://www.rauschenbergfoundation.org/artist/oral-history/sidney-felsen.

- 1Hiroko Ikegami, The Great Migrator: Robert Rauschenberg and the Global Rise of American Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010), 7.

- 2“The Reminiscences of Asha and Suhrid Sarabhai,” interview with Asha Sarabhai conducted by Cameron Vanderscoff and Gina Guy on March 18, 2015. Robert Rauschenberg Oral History Project. Columbia Center for Oral History Research, Columbia University in the City of New York and Robert Rauschenberg Archives. http://www.rauschenbergfoundation.org/Artist/oral-history/asha-and-suhrid-sarabhai, 21.

- 3Ibid., 79.

- 4Ibid., 82.

- 5Ibid., 27.

- 6Ibid., 47.

- 7“The Reminiscences of Sidney Felsen,” interview conducted by James McElhinney on November 9, 2013, and December 13, 2013. Robert Rauschenberg Oral History Project. Columbia Center for Oral History Research, Columbia University in the City of New York and Robert Rauschenberg Archives, http://www.rauschenbergfoundation.org/artist/oral-history/sidney-felsen, 116.

- 8“The Reminiscences of Asha and Suhrid Sarabhai,” 41.