The German Democratic Republic’s (GDR) reputation as a dour socialist state falls away in Sara Blaylock’s essay, which examines the overlooked performance art movement in 1980s East Germany. Professor, scholar, and writer Blaylock considers festivals, art collectives, and exhibitions as largely independent developments from the West. From action painting to free-form music concerts, East German performance art establishes itself in the GDR’s final decade.

Performance art defined the experimental scene in the German Democratic Republic’s (GDR) final decade. Significantly, its emergence took place not only in independent spaces but also in official ones. The turn to performance art thus represented both an innovative claim to artistic autonomy and a redefinition of the state’s cultural protocol, not least of which was the way it defined the relationship between art and public space.

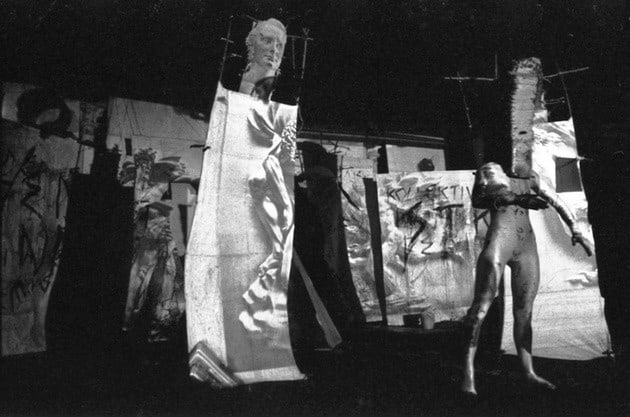

The first major event to feature performance art on a large scale took place in June 1985. The Intermedia I festival, held at a state-run cultural center outside of Dresden, followed several years’ worth of experimentations with the body in smaller venues (from private studios to art school classrooms).1In fact, the first performance art in East Germany is sometimes attributed to Robert Rehfeldt (I Am Staying in the GDR, 1953). The scale and public profile of the event affirmed the significance of the performance art form to the GDR’s creative subculture. The festival’s opening night featured Lutz Dammbeck’s Hercules Concept—a live multimedia collaboration with the dancer Fine Kwiatkowski that wove together film, dance, sculpture, sound, and language. Despite some clear rejections by the national film studio, Deutsche Film Aktiengesellschaft (DEFA),2Dammbeck was a trained graphic designer and worked for many years as an animator with the DEFA studio. Dammbeck enjoyed significant privileges from the state, including reviews of his “media collages” in major publications and invitations to perform on important state stages, including the Bauhaus Dessau.

Other highlights from the Intermedia I weekend included a screening-cum-live-performance of one of the Structures films, which the painter and filmmaker Christine Schlegel had made with Kwiatkowksi. These projects were offshoots of Schlegel’s work with the SUM Theater, an association of eight artists and musicians that produced collaborative performance projects from 1982 to 1984 in Dresden. The group made a number of films, often involving action painting or some kind of movement, but no documentation of their live performances was ever made. In fact, SUM only performed a few times before an audience. With few models for performance art in the GDR, the form emerged as a mode of multimedia and collaborative experimentation that contested the state’s rigid hierarchies of genre and aesthetics.

Despite the fact that the Intermedia I organizers Christoph Tannert and Micha Kapinos had received official permission to hold the festival, the state reacted severely to the event. The club director was ultimately fired, and several artists received exhibition prohibitions. The state’s punitive reaction contradicted several decades of an increasingly flexible cultural bureaucracy.3For more on this, see Esther von Richthofen, Bringing Culture to the Masses. Control, Compromise, and Participation in the GDR (New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2009). Since the seventies, club directors had been quite free to program experimental work in officially run spaces. Tempestuous and unpredictable, the government nonetheless wielded its authority as it saw fit. A wave of artists including Dammbeck and Schlegel left East Germany on legal exit visas and resettled in West Germany shortly after Intermedia I.

Others elected to stay and build upon the momentum the event had ignited. This included Gabriele Kachold,4Today, the artist is known by her maiden name Stötzer. She has sometimes been known under the name Stötzer-Kachold. a writer, multimedia artist, and erstwhile political prisoner, who had screened a film at the festival. A year before Intermedia I, she began coordinating the GDR’s first feminist art collective, the Women Artists Group Exterra XX.5In German, the group’s official name is Künstlerinnengrupppe Exterra XX. The ever-changing group made collective films, designed and sold clothing, displayed their wares in fashion shows, and eventually turned to live performance. Through their collaborative work, the women established a solidarity network, which contested the restrictive definitions of art advanced by the state, while also confronting the latent misogyny in both the experimental arts scene and East German culture, writ large.

From about 1988 onward, Kachold’s art collective began to explicitly explore live performance. This shift signals the women’s amplified confidence, as well as the public’s growing interest in live artworks. In fact, the prevalence of performance art had increased exponentially in the past few years. Action painting and other process-oriented art practices became particularly popular and could be seen at both official and unofficial events.

Performance art developed in East Germany for the most part independently of movements in the West—and followed a similar “parallel”6Bojana Cvejić, “A Parallel Slalom from BADco: In Search of a Poetics of Problems,” Representations, no. 136 (Fall 2016): 21–35. development as witnessed across the Eastern Bloc.7See, for example, Amy Bryzgel, Performing the East: Performance Art in Russia, Latvia and Poland since 1980 (London: I. B. Tauris, 2013) and Klara Kemp-Welch, Antipolitics in Central European Art: Reticence as Dissidence under Post-Totalitarian Rule, 1956–1989 (London: I. B. Tauris, 2014). Nevertheless, the West German conceptual artist Joseph Beuys became an important point of reference for the GDR’s experimental scene. Beuys visited East Germany for the first and only time in 1981 as a guest of the West German diplomatic office. In 1984 the artist Erhard Monden, along with the curator Eugen Blume, attempted to bring Beuys once more to participate in a collaborative performance entitled Sender Receiver. After East German border guards refused Beuys entry, the project had to take place remotely—ultimately becoming a kind of conceptual cable connecting East and West.

Two years after Beuys’ death, the independent gallery EIGEN+ART in Leipzig programmed After Beuys, a month-long exhibition series in honor of the artist. Among the most memorable of the three projects was the performance Allez! Arrest! by three of the four members of the Auto-Perforation Artists, a collective based in Dresden.8The group also included Via Lewandowsky. Brendel, Gabriel, and Lewandowsky first met in 1982. Görß joined the set design program a few years later and participated in their first group public performance, Slowly Dampening, in 1985. For ten days Micha Brendel, Else Gabriel, and Rainer Görß locked themselves in EIGEN+ART and made projects that responded to their environment. Their mission was to break down the barriers between art and life, in the spirit of Beuys. In fact, EIGEN+ART founder, Judy Lybke, also names Beuys as an influence for the gallery, which he devised as a kind of social conduit between artists and the general public. Importantly, although EIGEN+ART was technically independent, Lybke found loopholes within state bureaucracy to help keep it open. He registered the gallery as the studio of a Union of Fine Artists member,9In fact, EIGEN+ART was technically designated a “workshop.” only invited union art historians to speak at his events, and eventually joined the union himself.

Significant changes to both official and unofficial artistic spaces precipitated a movement toward performance art in the late eighties. A blurring of institutional and experimental borders is perhaps best represented by the Auto-Perforation Artists, who first met as set design students at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts. With their first major public appearance in the performance Slowly Dampening, held at the art school in 1985, Brendel, Gabriel, Görß, and Via Lewandowsky introduced performance art as a product of the state’s own cultural and educational system. Working with structural and cultural impasse as a motivation rather than an obstacle, the Auto-Perforation Artists used creative restraint to redefine art in East Germany from within the institution itself.10I have used a similar description in my dissertation. See Sara Blaylock, “Infiltration and Excess: Experimental Art and the East German State, 1980–1989” (doctoral thesis, University of California—Santa Cruz, 2017), 80.

In fact, these artists helped to further legitimize performance art as a state-sanctioned art form. After graduating in 1987 with degrees in set design, Brendel, Gabriel, and Lewandowsky fought for—and gained—status as fine artists with the Union of Fine Artists. Such recognition guaranteed them greater financial and material benefits than usually were awarded set designers, who were considered craftspeople. Tannert and Blume, both union art historians, supported these artists both directly and indirectly in their simultaneous efforts to have performance art be officially recognized as an artistic medium by the state. En route to this formal recognition (which was in fact never fully realized), Tannert and Blume organized a union-sponsored performance art conference in the summer of 1989.

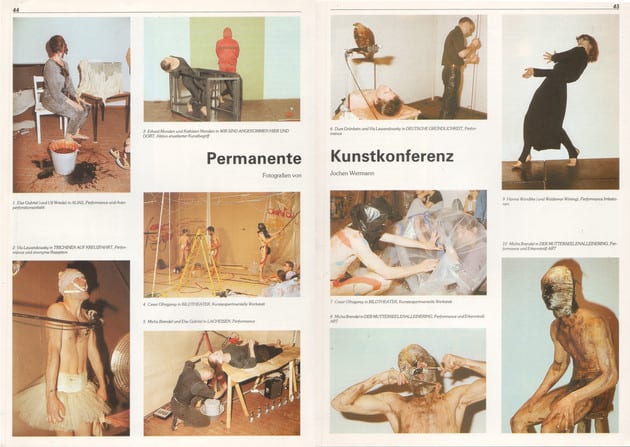

The Permanent Art Conference took place from May 30 to June 30 in the White Elephant Gallery, a major state-run space in East Berlin. The program included about twenty events. In addition to performances, there were other “actions,” including group paintings, conceptual workshops, lecture-performances, and concerts by free-form music groups. Programmed as part of the annual Berlin Regional Art Exhibition, the conference automatically achieved a high profile in official cultural media, and was covered widely in the state’s art magazine, Bildende Kunst (Plastic Arts). For the first time, the Union of Fine Artists had accepted performance art into its official program. In so doing, it broke with the rigid schematics and hierarchies of genre that had defined state culture for forty years.

The question thus remains as to how far the GDR’s performance art scene could have developed had this important event not been held so close to the country’s dramatic end on November 9, 1989. The wall’s destruction was, in effect, the country’s ultimate performance—a rapid and spontaneous break, which shed light on the hypocrisies and inadequacies of state culture that experimental artists had been exposing for more than a decade.

Further Reading

Barron, Stephanie and Sabine Eckmann, eds. Art of Two Germanys. Cold War Cultures. New York: Abrams, 2009. Exhibition catalog.

Blaylock, Sara. “Infiltration and Excess: Experimental Art and the East German State, 1980–1989.” Doctoral thesis, University of California—Santa Cruz, 2017.

Cvejić, Bojana. “A Parallel Slalom from BADco: In Search of a Poetics of Problems.” Representations, no. 136 (Fall 2016): 21–35.

Eckhardt, Frank, and Paul Kaiser, eds. Ohne uns! Kunst & alternative Kultur in Dresden vor und nach ’89. Dresden: Efau Verlag, 2009. Exhibition catalog.

Jappe, Elisabeth. Performance, Ritual, Prozeß. Munich and New York: Prestel-Verlag, 1993.

Kaiser, Paul. Boheme in der DDR. Dresden: Dresdner Institut für Kulturstudien, 2016.

Kaiser, Paul, and Claudia Petzold. Boheme und Diktatur in der DDR: Gruppen, Konflikte, Quartiere 1970–1989. Berlin: Fannei & Walz, 1997. Exhibition catalog.

Knaup, Bettina, Angelika Richter, and Beatrice E. Stammer, eds. Und jetzt: Künstlerinnen aus der DDR. Nuremberg: Verlag für moderne Kunst, 2009. Exhibition catalog.

Marlin, Constanze von, ed. Ordnung durch Störung. Auto-Perforations-Artistik. Nürnberg: Verlag für moderne Kunst, 2006. Exhibition catalog.

Muschter, Gabriele, ed. DDR Frauen fotografieren. Lexikon und Anthologie. Berlin: ex pose verlag, 1989.

Pejić, Bojana, ed. Gender Check: Femininity and Masculinity in the Art of Eastern Europe. Cologne: Walther König, 2009. Exhibition catalog.

——. Gender Check, A Reader: Art and Theory in Eastern Europe. Cologne: Walther König, 2010.

Tannert, Christoph. Ende vom Lied. Berlin: Künstlerhaus Bethanien, 2016. Exhibition catalog.

——. Gegenstimmen. Kunst in der DDR 1976–1989 (Voices of Dissent: Art in the GDR 1976–1989). Berlin: Deutsche Gesellschaft & Künstlerhaus Bethanien, 2016. Exhibition catalog.

- 1In fact, the first performance art in East Germany is sometimes attributed to Robert Rehfeldt (I Am Staying in the GDR, 1953).

- 2Dammbeck was a trained graphic designer and worked for many years as an animator with the DEFA studio.

- 3For more on this, see Esther von Richthofen, Bringing Culture to the Masses. Control, Compromise, and Participation in the GDR (New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2009).

- 4Today, the artist is known by her maiden name Stötzer. She has sometimes been known under the name Stötzer-Kachold.

- 5In German, the group’s official name is Künstlerinnengrupppe Exterra XX.

- 6Bojana Cvejić, “A Parallel Slalom from BADco: In Search of a Poetics of Problems,” Representations, no. 136 (Fall 2016): 21–35.

- 7See, for example, Amy Bryzgel, Performing the East: Performance Art in Russia, Latvia and Poland since 1980 (London: I. B. Tauris, 2013) and Klara Kemp-Welch, Antipolitics in Central European Art: Reticence as Dissidence under Post-Totalitarian Rule, 1956–1989 (London: I. B. Tauris, 2014).

- 8The group also included Via Lewandowsky. Brendel, Gabriel, and Lewandowsky first met in 1982. Görß joined the set design program a few years later and participated in their first group public performance, Slowly Dampening, in 1985.

- 9In fact, EIGEN+ART was technically designated a “workshop.”

- 10I have used a similar description in my dissertation. See Sara Blaylock, “Infiltration and Excess: Experimental Art and the East German State, 1980–1989” (doctoral thesis, University of California—Santa Cruz, 2017), 80.