Professor, author, and curator André Lepecki follows Brazilian artist Lygia Clark’s transition from visual arts to performance art although she refused that label. Part three of this essay reviews Clark’s confrontation and exploration of objects and temporality through her performance practices.

In addition to Lepecki’s essay, you can access installation views and the press release through MoMA’s online exhibition history archive here.

Performance and Lygia Clark

And yet . . . a paradox remains. If we shift our approach to a broader art-historical and cultural-historical perspective, we can understand Clark’s rejection of the categories of performance art, body art, and Happenings as something that paradoxically would include her in the history of performance art in its formative decades. In fact a number of her fellow artists engaging in corporeal propositions, collective propositions, antiobject propositions, aesthetic/political/healing propositions, and so on, shared a general feeling that “performance art” was an unhappy name for their work. As the art historian Kristine Stiles writes, “When the term ‘performance art’ gained currency in the burgeoning literature on action that appeared in the mid-1970s, many artists initially rejected it for the term’s connotations and association with traditional theater.”1Kristine Stiles, “Uncorrupted Joy: International Art Actions,” in Ferguson, ed., Out of Actions, p. 238. In this sense Clark’s rejection becomes her way of partaking in a sensibility shared by many of her peers, particularly during the years when she was working in Europe, from 1968 until her return to Brazil in 1976.

We can now say, then, that Clark’s relationship to performance is not so simple a matter after all. The fact remains that it is impossible to write on her collective propositions, or on Caminhando, or on her sensorial objects, or on her therapeutic practices, without invoking performance-related concepts. Brett, sensitive though he is to Clark’s singularity, uses several terms associated with performance and body art in discussing her work: “The proposal of Lygia Clark is embodied in the act, and enacted in the body. It exists in the moment that you do it or live it and nothing remains afterwards” (emphasis mine).2Brett, “Lygia Clark: Six Cells,” p. 17. Rolnik, another rigorous researcher into Clark, asked two French dance scholars, Laurence Louppe and Hubert Godard, to write for the catalogue of a 2005 exhibition she curated on the Estruturação do Self, and also published an essay there by the Portuguese philosopher José Gil, titled “Opening the Body.”Rolnik, De l’oeuvre à l’événement. The semantic field emerging from these texts is telling: words and phrases such as “act,” “embodied,” “body,” “in the moment,” “to do,” “live,” “movement,” and “nothing remains” clearly denote a conceptual field deemed ontological to performance. Yet performance theorists such as Peggy Phelan, Rebecca Schneider, Amelia Jones, Adrian Heathfield, Richard Schechner, Erika Fischer-Lichte, and others have defined performance as less a genre than an element or force, inflecting corporeality, ephemerality, embodiment, action, participation, lack of remainder, and liveness toward a specific (political and antirepresentational) class of effects in the world. Such would be the performative quality of performance. And Clark’s entire oeuvre after Caminhandoinvolves this particular force, prompting an understanding of the term “performance” in relation to her work after Caminhando as describing not a genre but an ethical, aesthetic, and political paradigm aimed at remaking the world.

Alongside Clark’s aesthetically and politically powerful works, insights, and propositions, a theory of performance could and perhaps should be rewritten—not to force her inclusion in the history of performance art, against her expressed wish, but to consider how that history might be reassessed under the force of her work. Through and with Clark’s work, not only the premises but the promises of performance might be reexamined. If performance theory has identified ephemerality, embodiment, presence, action, and participation as essential, even ontological, to performance, Clark scrambles, designifies, and resignifies these categories through a work, Rolnik writes, that “created a territory that did not exist until that moment, in which the modern project to reconnect art and life reached its limits.”3Rolnik, “Molding a contemporary Soul,” p. 102. In this “outlandish” territory lies the possibility of renewing performance art itself.4Deleuze has said that the closest word he has to describe what he and Félix Guattari mean by the concept of “deterritorialization” is the English word “outlandish.” Interviewed by Clare Parnet on the television program L’Abécédaire de Gilles Deleuze, filmed by Pierre-André Boutang, 1988–89; published as a set of DVDs by Semiotext(e)/Foreign Agents. The meanings of “outlandish” as “out there,” “foreign,” and “outrageous” are all relevant to the approach to Clark’s work as a consistent, ongoing series of propositions for a radical elsewhere of subjectivity, embodiment, and life. I suggest that Clark’s work and writings advance a critique of performative reason on at least four levels: a critique of time (linked to Clark’s notion of the “time-act”); a critique of objecthood (linked to her notion of the relational object); a critique of presence (linked to her notion of anonymity); a critique of participation (linked to her notion of immanence).

First Critique: Time (Or Act)

From Kaprow’s affirmations of the 1960s that Happenings “exist for a single performance, or only a few, and are gone forever as new ones take their place,” and that owing to their “planned obsolescence” they “should be unrehearsed and performed by nonprofessionals, once only,”5Kaprow, respectively “Happenings in the New York Scene,” 1961, “The Happenings Are Dead: Long Live the Happenings!,” 1966, and “The Happenings Are Dead,” all in Kaprow, Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life, pp. 17, 59, 63. to Phelan’s famous ontological diagnosis that “performance’s only life is in the present,”6Peggy Phelan, “The Ontology of Performance: Representation without Reproduction,” in Unmarked: The Politics of Performance (London and New York: Routledge, 1993), p. 146. the link between performance art and ephemerality has been strong. Clark held a different view: “The collective body cannot function once, as a happening.”7Clark, “O Corpo Coletivo,” p. 306. Indeed she spent an entire academic year collectively developing propositions with her students at the Sorbonne, and carried some of this work on to the next academic year. Her work was not at all a matter of privileging the ephemeral and making each piece only once. It involved a kind of accumulation in time, a continual return to the same problems, propositions, materials, and collectivity. And in each return, what was to be found was vital difference rather than dead obsolescence.

The moment for Clark, then, was not ephemeral, not a flicker of present time that was gone forever as soon as it had passed. As she explained in her short text “A propósito do instante” (On the instant), of 1965, “The act contains in itself its own overcoming, its own becoming.”8Clark, “A propósito do instante,” p. 155. Clark’s performative act was not subject to Kaprow’s “planned obsolescence,” neither can it be ontologically characterized as what “disappears into memory,” in Phelan’s phrase.9Phelan, “The Ontology of Performance: Representation without Reproduction,” p. 148. Instead, “The brute perception of the act is the future already making itself. Past and future are implied in the present-now of the act.”10Clark, “A propósito do instante,” p. 155. Every act is both multiplicity and singularity, both temporal rhizome and willed event, both dividing and synthesizing time. Clark herself phrased the dynamic like this: “The act of doing is time.”11Clark, “Do ato,” 1965, in Lygia Clark (Barcelona), p. 165. Author’s trans.

The consequences of this affirmation for performance theory are profound. Clark understood an act as leading the acting agent not into the past but into the elongated present/past/future of duration: “In the immanent act we do not perceive a temporal limit. Past, present, future mingle.”12Ibid., p. 165. As one performs an act, this act is already time, meaning that time is not a given, it is produced. Moreover: it must be produced in action. But what occasions Clark’s particular performative temporality is the ethical commitment to persist and commit oneself (singularly and collectively) to the proposition, and to wherever the proposition would take the collective. She once wrote to Hélio Oiticica, “I used to do my proposals two or three times and they ended up falling into Happenings. It satisfied neither myself nor the people that could not elaborate themselves as I wished. There was no participation at all.”13Clark, interview with Celina Luz, “Lygia Clark na Sorbonne: Corpo-a-corpo no desbloqueio para a vivência,” Vida das artes 1, no. 3 (August 1975):60. Author’s trans.

In this collectively fabricated time, one experiences a coherent fusion between experiential propositions, enduring persistence, and precarious materials. One endures, months pass, even years may go by. And in time passing, what endures is a vital return that makes the collective body into a collective subjectivity, that turns its experiments and immanent time-acts into modes of existence, liberating and producing a deeper consistency for living life. (Clark once wrote of longing to live “like the hand of a clock; passing a thousand times through the same route.”)14Clark, quoted in Peter Eleey, The Quick and the Dead, exh. cat. (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2009), p. 41. This temporal-subjective-corporeal-collective fabrication happens most profoundly in Baba antropofágica, but it is all already there in the apparently solitary Caminhando, which allowed Clark to see for the first time that “there is only one type of duration: the act.”15Clark, “Caminhando,” p. 152.

Second Critique: Object (or Precarious Thing)

Should the idea and fact of objecthood matter to performance? Isn’t the force of performance art predicated on a generalized critique of the object as the privileged center of aesthetic investment? Perhaps.

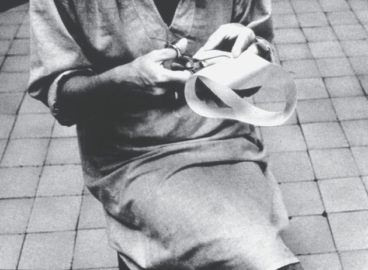

Clark’s critique of objecthood was inflected by her philosophically and politically sophisticated understanding of what linked the many temporalities informing an immanent act with the many temporalities embedded in ephemeral materials. She discovered the immanence of what we may call her act-duration, or time-act, by discarding the notion not only of a built object but also of a found object or readymade: “When an artist uses an object from daily life (a ready-made object), he intends to give this object a poetic power. My Caminhando is very different. In its case there is no need for the object: it is the act which engenders the poetry.”16Clark, “On the Magic of the Object,” in Lygia Clark(Barcelona), p. 152. Here Clark clarifies not only her replacement of the object with the act, but also how that act, in Caminhando, must not be seen as generating another kind of object, one representing an “everyday gesture.” This is crucial: the act of cutting in Caminhando is not a re-presentation of an everyday act, not a Duchampian strategy transposed into performance, of the kind seen in Kaprow’s 18 Happenings in 6 Parts (1959), for instance, when a woman presses and drinks orange juice, or in some of Grand Union’s “task-based” actions, such as carrying boxes or mattresses.17It is surprising to see Laurence Louppe, a lucid scholar and theorist of dance, proposing this analogy in her essay in Rolnik’s De l’oeuvre à l’événement, p. 38. In Caminhando, the object of the proposition (which we could even call a score) is not the creation of another object, nor the treatment of behavior as an object, but the creation of a particularly intense experience tied to the precariousness of a material: the immanence of the act.

In 1966, when Clark began to make her Objetos sensoriais, she wrote, “We propose the precarious as the new concept of existence against all static crystallization of duration.”18Clark, “We refuse . . . ,” 1966, in Bois, “Nostalgia of the Body,” p. 106. The Brazilian performance artist and theorist Eleonora Fabião has linked Clark’s privileging of precariousness and precarious materials to the temporalities of her politics and to a theory of contemporary performance. Fabião suggests a “temporal quality made possible by precariousness,” and “a mode of temporality acutely related to ‘poor’ materiality.” As she convincingly explains, the “temporality of precariousness differs from, as well as adds to, ‘ephemerality’ (the term usually used to conceptualize the temporal aspect of live art).”19Eleonora Fabião, “On Precariousness and Performance: 7 Actions for Rio de Janeiro,” Women and Performance 20, no. 1 (March 2010):109–10. In a language quite similar to Clark’s, Fabião concludes, “A bio-poetics and a bio-history of precariousness approximate time and matter in such a way that their claims for autonomy are diluted; indeed, precariousness is the performance of time and matter’s distinct sameness: time becomes a force of matter and matter becomes a force of time.”20Ibid., p. 110. Following Fabião’s argument, we can understand Clark’s embrace of precariousness as less an embrace of the ephemeral than a potent affirmation of what remains: the immanent, transtemporal experience of the act’s overcoming of its objecthood as it is performed. Perhaps the critic and curator Paulo Venâncio—still bearing the relational objects that Clark had placed on him during a therapy session, and barely yet returning to language—was nevertheless right when he carefully called those fantastical/mundane objects “things.” It is in the precarious dignity of the thing that Clark’s critique of objecthood is most potent, anticipating Mario Perniola’s insight that “to give oneself as a thing that feels and to take a thing that feels is the new radical experience that asserts itself on contemporary feeling.”21Mario Perniola, The Sex Appeal of the Inorganic, trans. Massimo Verdicchio (London and New York: Continuum, 2004), p. 1.

Third Critique: Presence (or Anonymity)

We have already seen how Clark admonished body and performance art for not going far enough in their critique of art: both, she felt, mistook the replacement of the art object with the artist’s body for radicality. To Clark, this replacement was only a displacement: the body of the artist became the new art object, the object of contemplation, even admiration. She also saw ethical and political complications in a kind of narcissism, a martyrology, an unbearable epideictic mode of praise and self-praise for the newly glorified presence of the artist. Just as Clark had problematized the question of the support in painting and sculpture, she also addressed the question of the subject as the living support of his or her own expression: “artists who no longer make objects but, instead, propositions turn themselves into superstar characters [personagens super-vedetes] to compensate for the anonymity of a work’s authorship. This is where a whole catharsis and regression invades the processual field.”22Clark, “O homem como suporte vivo de sua própria expressão,” n.d. Typescript in the archives of the Associação Cultural “O Mundo de Lygia Clark.” Author’s trans.

We can now understand why, as Bois has written, Clark’s “entire oeuvre aims in some way at the disappearance of the author.”60 In her own words, she sought the dissolution of artist and object into a life (or “living structure”) divorced from both martyrological presence and heroic genius: “I become terrified of being the catalyst for my propositions. I want people to live them and interject their own myth, independently of me.”23Clark, “On the Suppression of the Object (Notes),” p. 267. At a time when neoliberal forces increasingly create subjectivities based on daily social self-presentation as virtuoso creators,24See Paolo Virno, A Grammar of the Multitude, trans. Isabella Bertoletti, James Cascaito, and Andrea Casson (New York: Semiotext(e), 2004). Clark’s notion of performativity as a force leading to anonymous, impersonal subjectivities is crucial. “What’s important is the the act of doing, in the present,” she wrote; this doing fuses subject and object, thus “achieving the anonymous work”—“the artist is dissolved into the world.”25Clark, “A Propósito da Magia do Objeto,” 1965, in Lygia Clark (Barcelona), p. 153. Author’s trans. Just as the object must escape its traps and become a precarious thing, the author and the participant must escape what Esposito calls the “dispositif-person” to also become an anonymous thing.26In his book Third Person, Robert Esposito engages in an archaeology of the concept of the person in Western juridical tradition, from Rome to contemporaneity. For Esposito, “the ‘dispositif’ of the person” (p. 9) is the particularly perverse mode of alienated subjectivity upon which the entire Western juridical tradition is built, and is predicated on the “fact that the person is specifically defined by the distance that separates it from the body” (p. 9). Moreover, “to experience personhood fully” (p. 10) means to push others to lives of exclusion, abjection, lack of rights, enslavement, etc. See Esposito, Third Person(Cambridge: Polity Press, 2012). We can thus understand Clark’s confession of wanting to be just anonymous thing: “Thus sometimes, this nostalgia of being a wet stone, a stone-being under the shade of a tree, on the banks of time.”27Clark, “Caminhando,” p. 152.

Fourth Critique: Participation (Or Immanence)

The three previous critiques (re-)qualify Clark’s notion of participation. For her, participation was not simply taking part; it required an added element without which it was only empty interactivity, empty play. A letter to Clark from Oiticica makes this point well: “For you the most important is the discovery of the [body] . . . and not the ‘participation in a given object,’ because this relationship with the object (subject-object) is overcome . . . while in general the problem of participation keeps this relation.”28Oiticica, letter to Clark, n.d., in Cartas, p. 115. This is quite close to Félix Guattari’s definition of participation as not only “being a part” but “a collective subjectivity investing a certain kind of object, and putting itself in the position of an existential group nucleus.”29Félix Guattari, Chaosmosis. An Ethico-aesthetic Paradigm, trans. Paul Bains and Julian Pefanis (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1995), p. 25. For Clark, participation surpassed the weak force that Brian Massumi calls “interaction” in some forms of art, where participants are just excitedly moving objects around and fulfilling the gestural options that have been given to them, registering only their conformity to a codified situation rather than transforming and reinventing the relation itself.30See Massumi, Semblance and Event, p. 46. But it also surpassed the passive participation of Jacques Rancière’s “emancipated spectator,” when what matters is the reflexive-perceptive exploration of “dissensual distributions of the sensible” offered by artworks as sufficient political and aesthetic labor.31See Jacques Rancière, The Emanci-pated Spectator, trans. Gregory Elliott (New York: Verso, 2009). For a critique of this contemporary passive progressivism see André Lepecki, “From Partaking to Initiating,” in Gerald Siegmund and Stefan Hölscher, eds., Dance, Politics and Co-Immunity (Zürich and Berlin: Diaphanes, 2012), pp. 21–38.

The project of participation is totally different in Clark’s work. One does not move what is given, one does not aim at “participation in a given object,” as Oiticica wrote; one certainly is not a “spectator,” emancipated or not. Instead one gives oneself to a practice of overcoming a world in which these terms still signify a fossilization of experience and subjectivity according to a conformity of behaving and appearing—even of appearing to be radically “artistic.” Clark wrote, “Here, it is not participation for participation’s sake . . . but that the participant gives a meaning to his gesture and that his act be fed by a thought, in this case one that emphasizes his freedom of action.”32Clark, “On the Magic of the Object,” p. 153. It is clear, then: one participates not in an artwork, but in constructing a collective space-time for the “experimental exercise of freedom”—Mário Pedrosa’s famous phrase that Clark, as early as 1965, claimed for herself in order to describe her own practices.33Pedrosa, quoted in ibid. Curiously, Clark misquotes Pedrosa, replacing “experimental” with “spiritual.” As for Pedrosa’s sentence itself, it has been quoted profusely in the literature on twentieth-century Brazilian art, but these quotations rarely cite an original source. Noéli Ramme, in her long essay “Arte como exercício experimental da liberdade” (available online at http://abrestetica.org.br/deslocamentos/f02.swf), writes that the sentence appeared in print for the first time in March 1968, in an essay by Pedrosa in Correio da Manhã commenting on the French critic Pierre Restany. The Brazilian artist Antonio Manuel, however, in his essay “O Corpo é a Obra,” cites a review of his work by Pedrosa, from c. 1970, where the critic writes, “What Antonio is doing, with his gesture presenting itself as work, is the experimental exercise of freedom [é o exercício experimental da liberdade].” Manuel, “O Corpo é a Obra,” Item-4. Sexualidades, November 1996, p. 33. Author’s trans. Rina Carvajal, curator of an important exhibition titled after Pedrosa’s expression at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, in 1999, claims that he “coined the phrase” in his 1970 article “A Bienal de cá para lá.” Carvajal, “The Experimental Exercise of Freedom,” The Experimental Exercise of Freedom, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, 1999), p. 35. Since Clark used the sentence in 1965, the source remains obscure. What matters here is how Clark embraced the expression. Clark quoted her friend’s phrase in her text “On the Magic of the Object,” but misquoted it, instead writing “the spiritual exercise of freedom.”34Clark, “On the Magic of the Object,” p. 153. As Rolnik has suggested, this was something other than a slip demanding an editor’s correction.35Rolnik, De l’oeuvre à l’événement, p. 26 n. 70. Rather, the experimental, spiritual, corporeal, collective exercise of freedom, where thought and action fused in a plane of consistency through the immanence of the time-act, was the last frontier of Clark’s singular quest for an affective geometry of living. Perhaps another name for it, thanks to “all the potentialities contained in the empty-full, whose meaning is given by the act,”36Clark, “On the Act,” 1965, in Lygia Clark (Barcelona), p. 165. Translation modified. could have been this one: performance.

This is the third and final section of an essay by André Lepecki on the Brazilian artist Lygia Clark, excerpted from the exhibition catalog Lygia Clark: The Abandonment Of Art, 1948-1988, available at the MoMA bookstore. Read the first section here and the second section here.

- 1Kristine Stiles, “Uncorrupted Joy: International Art Actions,” in Ferguson, ed., Out of Actions, p. 238.

- 2Brett, “Lygia Clark: Six Cells,” p. 17.

- 3Rolnik, “Molding a contemporary Soul,” p. 102.

- 4Deleuze has said that the closest word he has to describe what he and Félix Guattari mean by the concept of “deterritorialization” is the English word “outlandish.” Interviewed by Clare Parnet on the television program L’Abécédaire de Gilles Deleuze, filmed by Pierre-André Boutang, 1988–89; published as a set of DVDs by Semiotext(e)/Foreign Agents. The meanings of “outlandish” as “out there,” “foreign,” and “outrageous” are all relevant to the approach to Clark’s work as a consistent, ongoing series of propositions for a radical elsewhere of subjectivity, embodiment, and life.

- 5Kaprow, respectively “Happenings in the New York Scene,” 1961, “The Happenings Are Dead: Long Live the Happenings!,” 1966, and “The Happenings Are Dead,” all in Kaprow, Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life, pp. 17, 59, 63.

- 6Peggy Phelan, “The Ontology of Performance: Representation without Reproduction,” in Unmarked: The Politics of Performance (London and New York: Routledge, 1993), p. 146.

- 7Clark, “O Corpo Coletivo,” p. 306.

- 8Clark, “A propósito do instante,” p. 155.

- 9Phelan, “The Ontology of Performance: Representation without Reproduction,” p. 148.

- 10Clark, “A propósito do instante,” p. 155.

- 11Clark, “Do ato,” 1965, in Lygia Clark (Barcelona), p. 165. Author’s trans.

- 12Ibid., p. 165.

- 13Clark, interview with Celina Luz, “Lygia Clark na Sorbonne: Corpo-a-corpo no desbloqueio para a vivência,” Vida das artes 1, no. 3 (August 1975):60. Author’s trans.

- 14Clark, quoted in Peter Eleey, The Quick and the Dead, exh. cat. (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2009), p. 41.

- 15Clark, “Caminhando,” p. 152.

- 16Clark, “On the Magic of the Object,” in Lygia Clark(Barcelona), p. 152.

- 17It is surprising to see Laurence Louppe, a lucid scholar and theorist of dance, proposing this analogy in her essay in Rolnik’s De l’oeuvre à l’événement, p. 38.

- 18Clark, “We refuse . . . ,” 1966, in Bois, “Nostalgia of the Body,” p. 106.

- 19Eleonora Fabião, “On Precariousness and Performance: 7 Actions for Rio de Janeiro,” Women and Performance 20, no. 1 (March 2010):109–10.

- 20Ibid., p. 110.

- 21Mario Perniola, The Sex Appeal of the Inorganic, trans. Massimo Verdicchio (London and New York: Continuum, 2004), p. 1.

- 22Clark, “O homem como suporte vivo de sua própria expressão,” n.d. Typescript in the archives of the Associação Cultural “O Mundo de Lygia Clark.” Author’s trans.

- 23Clark, “On the Suppression of the Object (Notes),” p. 267.

- 24See Paolo Virno, A Grammar of the Multitude, trans. Isabella Bertoletti, James Cascaito, and Andrea Casson (New York: Semiotext(e), 2004).

- 25Clark, “A Propósito da Magia do Objeto,” 1965, in Lygia Clark (Barcelona), p. 153. Author’s trans.

- 26In his book Third Person, Robert Esposito engages in an archaeology of the concept of the person in Western juridical tradition, from Rome to contemporaneity. For Esposito, “the ‘dispositif’ of the person” (p. 9) is the particularly perverse mode of alienated subjectivity upon which the entire Western juridical tradition is built, and is predicated on the “fact that the person is specifically defined by the distance that separates it from the body” (p. 9). Moreover, “to experience personhood fully” (p. 10) means to push others to lives of exclusion, abjection, lack of rights, enslavement, etc. See Esposito, Third Person(Cambridge: Polity Press, 2012).

- 27Clark, “Caminhando,” p. 152.

- 28Oiticica, letter to Clark, n.d., in Cartas, p. 115.

- 29Félix Guattari, Chaosmosis. An Ethico-aesthetic Paradigm, trans. Paul Bains and Julian Pefanis (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1995), p. 25.

- 30See Massumi, Semblance and Event, p. 46.

- 31See Jacques Rancière, The Emanci-pated Spectator, trans. Gregory Elliott (New York: Verso, 2009). For a critique of this contemporary passive progressivism see André Lepecki, “From Partaking to Initiating,” in Gerald Siegmund and Stefan Hölscher, eds., Dance, Politics and Co-Immunity (Zürich and Berlin: Diaphanes, 2012), pp. 21–38.

- 32Clark, “On the Magic of the Object,” p. 153.

- 33Pedrosa, quoted in ibid. Curiously, Clark misquotes Pedrosa, replacing “experimental” with “spiritual.” As for Pedrosa’s sentence itself, it has been quoted profusely in the literature on twentieth-century Brazilian art, but these quotations rarely cite an original source. Noéli Ramme, in her long essay “Arte como exercício experimental da liberdade” (available online at http://abrestetica.org.br/deslocamentos/f02.swf), writes that the sentence appeared in print for the first time in March 1968, in an essay by Pedrosa in Correio da Manhã commenting on the French critic Pierre Restany. The Brazilian artist Antonio Manuel, however, in his essay “O Corpo é a Obra,” cites a review of his work by Pedrosa, from c. 1970, where the critic writes, “What Antonio is doing, with his gesture presenting itself as work, is the experimental exercise of freedom [é o exercício experimental da liberdade].” Manuel, “O Corpo é a Obra,” Item-4. Sexualidades, November 1996, p. 33. Author’s trans. Rina Carvajal, curator of an important exhibition titled after Pedrosa’s expression at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, in 1999, claims that he “coined the phrase” in his 1970 article “A Bienal de cá para lá.” Carvajal, “The Experimental Exercise of Freedom,” The Experimental Exercise of Freedom, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, 1999), p. 35. Since Clark used the sentence in 1965, the source remains obscure. What matters here is how Clark embraced the expression.

- 34Clark, “On the Magic of the Object,” p. 153.

- 35Rolnik, De l’oeuvre à l’événement, p. 26 n. 70.

- 36Clark, “On the Act,” 1965, in Lygia Clark (Barcelona), p. 165. Translation modified.