Centro Espacial Satelital de Colombia (2015) is a video by Colombian artist collective La Decanatura. Reflecting on this work, Luis Pérez-Oramas, the Estrellita Brodsky Curator of Latin American Art, shares his personal experience as a curator and a poet. He further examines the museum’s often contradictory role in finding, rethinking, or even creating a voice for previously overlooked regions in the history of modernism. This essay is an excerpt from a local report from the C-MAP Latin America Trip to Colombia (forthcoming).

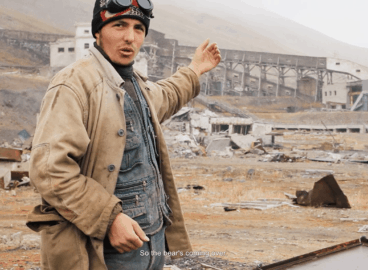

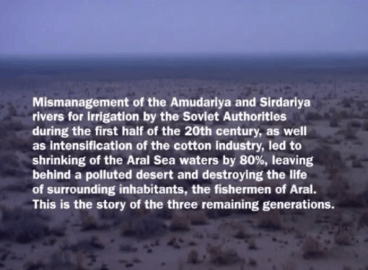

The very first scene of the video Centro Espacial Satelital de Colombia, by the art collective La Decanatura, depicts a mother cow slowly, even lovingly, stroking with her tongue a newborn calf, presumably her own. The landscape is pastoral and magnificent in its Arcadian calm, but for two uncanny architectural presences: two monumental satellite towers dating from the 1970s.

The place is known as the Centro Espacial Satelital de Colombia (Satellite Space Center of Colombia) and, like many similar sites throughout Latin America, it was opened in the 1970s, specifically on March 25, 1970.

The video, introduced by two black-and-white photographs of the towers, was authored by a collective of young Colombian artists, La Decanatura (Elkin Calderón and Diego Piñeros), and presented among many works in the National Salon of Artists in Pereira.

I still have this video in mind. It is one of the strongest, most moving art pieces I have seen in recent months. It obliquely touches upon some of the issues that I have been personally interested in, both as a curator and as a poet. The experience of seeing it actually drew me to the writing of some verses, maybe a poem, as well as to the memory of some old, haunting readings, and to general thinking about the purpose (or purposelessness) of an initiative such as a trip by MoMA curators to Colombia within the frame of our Contemporary and Modern Art Perspectives initiative, C-MAP.

Were we bound there with the expectation of discovering some (hidden) masterpieces? Do we really care about the history of a country such as Colombia—or for that matter about any other (relatively small) country in the Americas, or in the world? What is our position, as employees of a dominant, mainstream art institution, vis-à-vis the struggles and celebrations of national communities that are not planned to be part of the fairy tales embodied by our geniuses and artistic heroes? Could an institution such as MoMA be generous? Could an American, or for that matter international, curator working in the very axis of art power produce a critical perspective outside of a logic of power-will? What is a powerless art? A powerless Modernity: does it exist?

After the cow has caressed her newborn calf with her tongue, the video proceeds to show the rainy surrounding landscape of the very old Leal y Noble Villa de Santiago de Chocontá, in Cundinamarca.

Suddenly, sparingly, a group of children, all bearing musical instruments and wearing white costumes, which we presume were the uniforms of the technicians who worked at the Satellite Space Center, come out from those monster towers into the open field. They start playing a moving song, a lullaby. They caringly play that music while it slowly rains. In another shot, they play inside the abandoned towers, uncannily, against the silence of a failed Modernity.

They may be playing their music in search of a voice that they have lost, or the voice that they are losing as they become adults, and they look for the place of infancy, where they come from, that place that we all have abandoned: that site of absence projected into the future, uncertainly.

The Satellite Space Center is no longer useful, no longer “modern.” Beside its ruins of modernity, the landscape continues, beyond itself, following the same secular, ever-evolving pace of cows, trees, tempests, veals, harvests, lightning storms. A verse by Alberto Caeiro, one of Fernando Pessoa’s heteronyms, reads, “Os pastores de Virgílio, coitados, são Virgilío, / E a Natureza é bela e antiga.”’ (Virgil’s shepherds, poor guys, are Virgil, / And Nature is beautiful and ancient).

The Banda Sinfónica Infantil de Chocontá (Children’s Symphonic Band of Chocotá) ends its lullaby outside the satellite towers as the rain recedes. Each child turns away, one at a time, and goes inside. The day is ending. From above, from a hill maybe, we see the landscape of Chocontá entering the darkness of the night, gray mirrors of water slipping toward the horizon.

Few days, too many places: Medellín, Cali, Pereira, Armenia, Bogotá. A country emerging from a century of wars, from innumerable lost. A community rethinking itself, projecting for the first time, as a possible achievement, a future of peace. Artists getting together, making art there, where it was not possible to make art before. Is there a more exciting encounter? Do we need to expect there, as good old colons, the illusory greatness of art, the fiction of genius, the phantom of masterworks to feed our insatiable, Saturnine capitalization of the modern . . . instead of—Agamben’s dixit—just the upcoming, ordinary community?

I will keep with myself, for years, this brief encounter with La Decanatura’s view of Chocontá, the lullaby addressed to the absent, the dove’s coo intended for those who have not yet come as a testimony of something that, for the most, I think contemporary art has unfortunately lost.

We have lost an ambition. An ambition that consists of addressing those who are no longer with us, or those who have not yet (be)come. This deep ambition of temporal projection, of resilience against the precariousness of the present time; this will against the preterition of the absent; this illusion of making connection with that which we were, or with those who were, or with that which is the place from whence we come, and never were, was the driving ambition of art, at least since its intellectual regime was theoretically established in the Western world. It has been one of the most recurring figures of transcendence, that human impulse. That is what seems to have been lost in a world of art that only satisfies itself with the present; that aims only to be contemporary; that surges in cowardly silence against all forms of anachronism; that satisfies itself with a contempt of politics consisting in neutralizing it in its very mediocre scenes of representation; that feeds itself with its own commercial fetishizing, with its own, imperturbable economy. That conforms itself with its own present being, as if the darkness of the present or the uncertainty of the future were nonexistent; that satiates itself with its own fashions, happy to not be anything more than what it is, as all fashions, ceaseless, expiring from the anodyne exhaustion of its consumers.

It is against that world that the kids of Chocontá are singing.