In this essay, art historian Anna Pravdová delves deep into the MoMA Archives to highlight the Museum’s first exhibition of Czech art. Opened in May 1943, at the height of World War II, the exhibition War Caricatures by Hoffmeister and Peel featured works on paper by Adolf Hoffmeister and Antonín Pelc, recent immigrants and passionate anti-Fascists. It was successful due to its strong sarcastic humor, which Americans embraced in a time of crisis. The first part of the essay looks at the steps that led up to the exhibition, namely Hoffmeister’s and Pelc’s journeys to the United States. This second part considers closely the works on view.

In addition to Pravdová’s commentary, you can access the exhibition’s checklist and press release in MoMA’s comprehensive online exhibition history archive here.

At MoMA, Adolf Hoffmeister and Antonín Pelc displayed war caricatures they produced between 1941 and 1943. According to the checklist in the MoMA Archives, Hoffmeister displayed twenty-two caricatures and Antonín Pelc twelve, most of them responding vigorously to contemporary events in global politics.

The artists likely ended up at MoMA thanks to Hoffmeister’s previous contacts with the Museum’s founding director Alfred H. Barr Jr., whom Hoffmeister met on his first trip to the United States in 1936. The two immediately found common ground.1Hoffmeister recalls this meeting in his book Americké houpačky (American swings) (Prague: ELK, 1937): 173–74. Their relations deepened when Barr traveled to Europe in the late 1930s, as Hoffmeister recalls in his book Čas se nevrací (Time never goes back): “Once before the war, Alfred Barr Jr. visited Prague while on a trip to Europe. He was one of the most responsible pioneers of modern art in the United States of America and, then, was the director of the nascent Museum of Modern Art in New York City. He stayed at my place for several days. I don’t know why—whether his money ran out or what. […] We sat up late every night talking about questions that were ahead of reality and loomed larger the longer we talked about them.”2Adolf Hoffmeister, “Dadamonteur John Heartfield,” in Čas se nevrací (Time never goes back) (Prague: Československý spisovatel, 1965): 188.

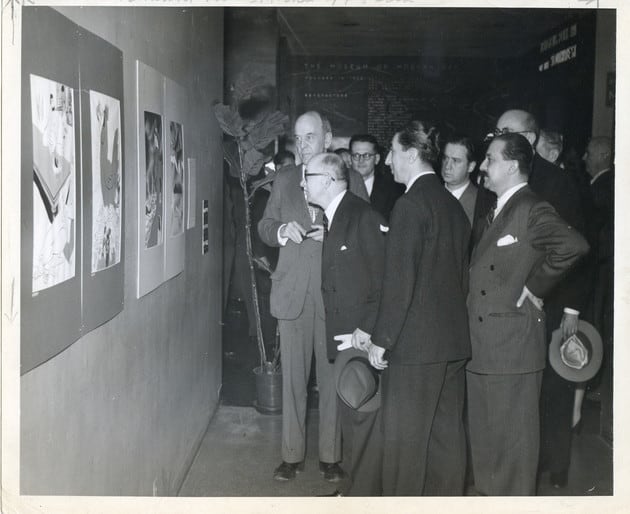

Hoffmeister revived these prewar encounters with Barr and certainly knew how to take advantage of the planned visit of Czechoslovak President in exile Edvard Beneš to the United States for the promotion of the exhibition. Though Beneš did see the exhibition, he was not at its opening (despite the majority of art history sources stating that it was he who opened it). The exhibition opened on May 11, but Beneš arrived in New York City on May 19 and visited the museum the next day in the company of Czechoslovak Ambassador Vladimír Hurban; Jan Papánek, Head of the Czechoslovak Foreign Department; General Consul Karel Hudec; envoy Jaromír Smutný; Colonel Oldřich Španiel; Beneš’s secretary Edvard Táborský; and several others.3Beneš arrived in the United States on May 7 and stayed for one month. He visited New York City several times during his stay, but didn’t see the exhibition until May 20, as corroborated by contemporary press reports. See, among others, “President Beneš v Museum of Modern Art a mezi průmyslníky,” Nedělní New-Yorské listy 53, no. 23 (May 23, 1943): 3. At the Museum, he was personally greeted by Barr, the new chairman of the Board of Trustees Stephen C. Clark, as well as other senior staff. Naturally, Hoffmeister and Pelc gave Beneš a guided tour of the exhibition. Nevertheless, the question is why did Beneš not open the exhibition (or why was its opening not timed to accommodate his schedule). We can only wonder whether an official support for left-leaning artists was discouraged.

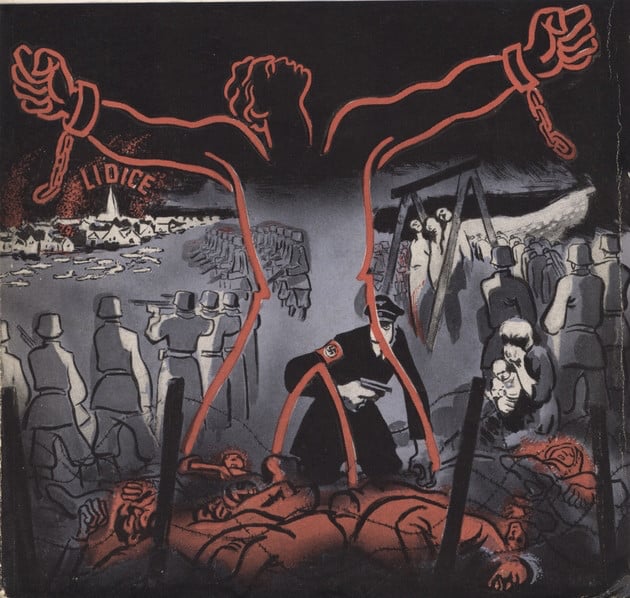

Lidice Shall Live

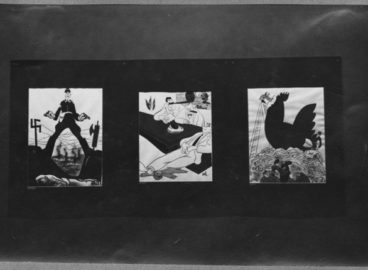

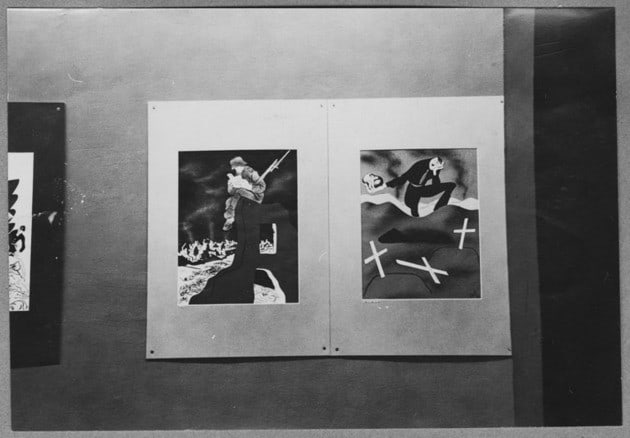

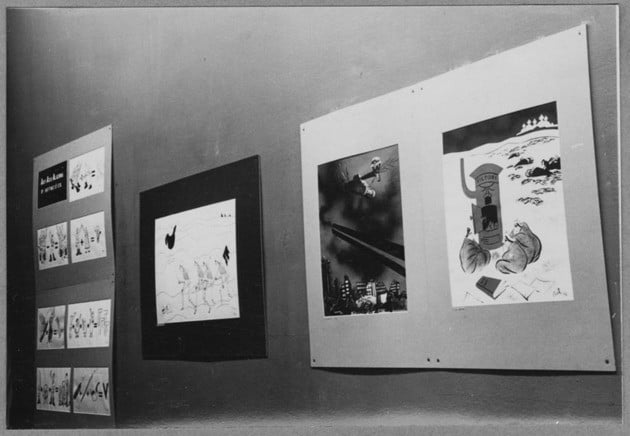

Unfortunately, not all the exhibited works are listed in the checklist. For example, based on documentary photographs of the installation in the MoMA Archives, Pelc’s large-format drawing entitled Lidice, which dominated the entire exhibition, appears to be missing.

Pelc made this drawing in response to the horrifying news that the Czech village of Lidice had been razed by the Nazis. He depicted the act, whose sad first anniversary was being felt at the time of the exhibition. Indeed, among the information that reached America from warring Europe, the news of the assassination of Deputy Reich Protector Reinhard Heydrich by Czech parachutists and the destruction of Lidice that followed in the spring of 1942 had an especially powerful impact. Only then did many Americans understand the real face of Nazism, and a strong wave of disgust and solidarity arose not only among Czech expatriates but also among American citizens.4See for example Stanislav Budín, Věrni zůstali(They stayed faithful) (Prague: Orbis, 1947), 122–33. Many articles and novels were published, dozens of poems were written,5The poets included, among others, Edna St. Vincent Millay, William Rose Benét, Joseph Auslander, and Roderick Ginsburg. and several feature films were made.6For example, Hangmen Also Die! (about the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich and what followed), The Silent Village, Hitler’s Madman, and several others. Lidice became a symbol of Nazi cruelty, and many events were launched in support of the devastated town. Naturally, Czech artists exiled in the United States participated: Bohuslav Martinů composed an orchestral work denouncing the horrors, Lidice, which was performed throughout the country. Hoffmeister wrote the play The Blind Man’s Whistle, or Lidice, whose printed program was adorned with a drawing by Pelc, who also made the set design when the play was staged in the United States, with Voskovec directing.

In Washington D.C., the Lidice Lives Committee was established as part of the Writers’ War Board in September 1942. Its aim was to establish “a village named Lidice in each Allied country,” reaching a number of “30 to 36 Lidices all over the world by the end of the war.” As early as July 1942, at the initiative of the Chicago Sun-Times, the village of Marquette Gardens (also known as Stern Park Garden) in the northern suburbs of Joliet, Illinois, was renamed Lidice. U.S. sculptor Jo Davidson was asked by the Committee to make a statue called Lidice, which was later displayed in a large shop window outside New York City’s Grand Central Station. Beside it hung Pelc’s drawing Lidice with several other drawings by the well-known caricaturist William Gropper. Pelc’s drawing had been previously reproduced in the Philadelphia Inquirer, the corresponding text reporting that the original would be on permanent display in New York’s Freedom House.“7Lidice Lives On,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 22, 1942. (Pelc likely borrowed the drawing from Freedom House for the exhibition at MoMA.)

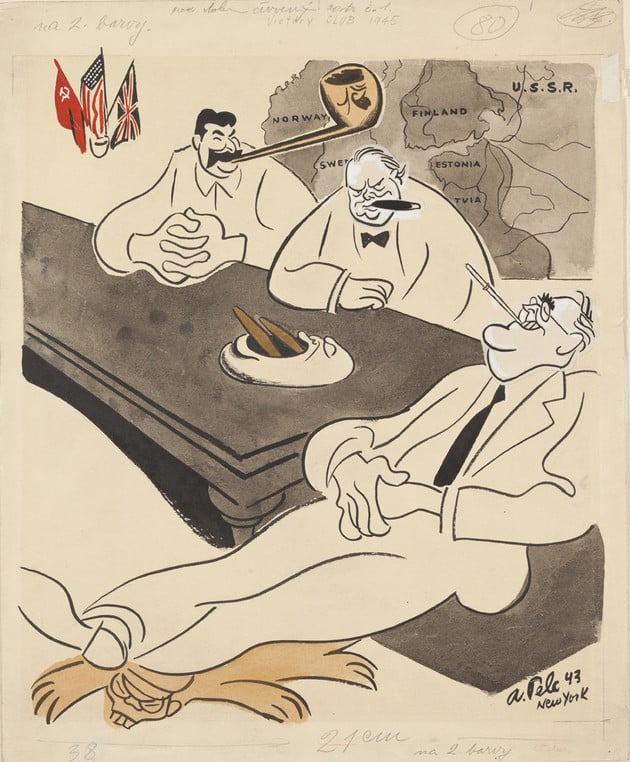

Pelc’s Vitriolic Drawings

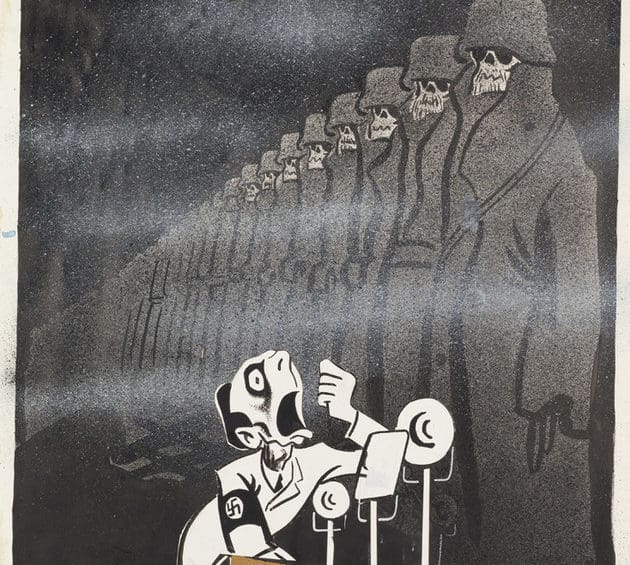

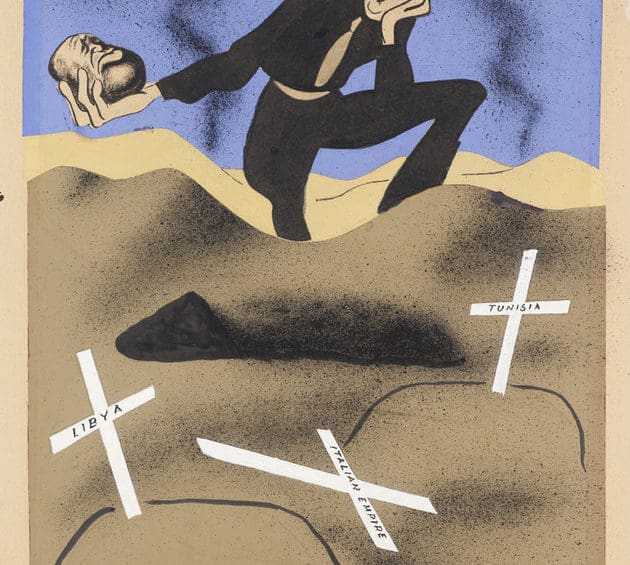

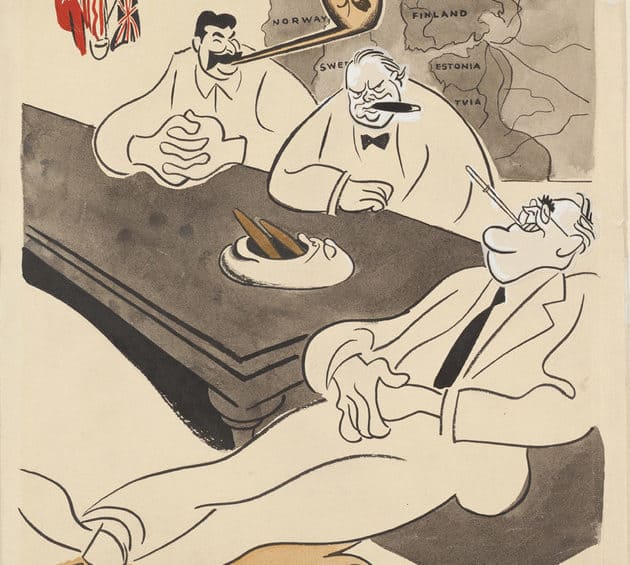

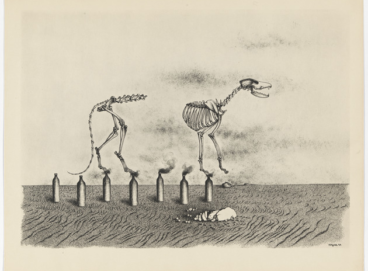

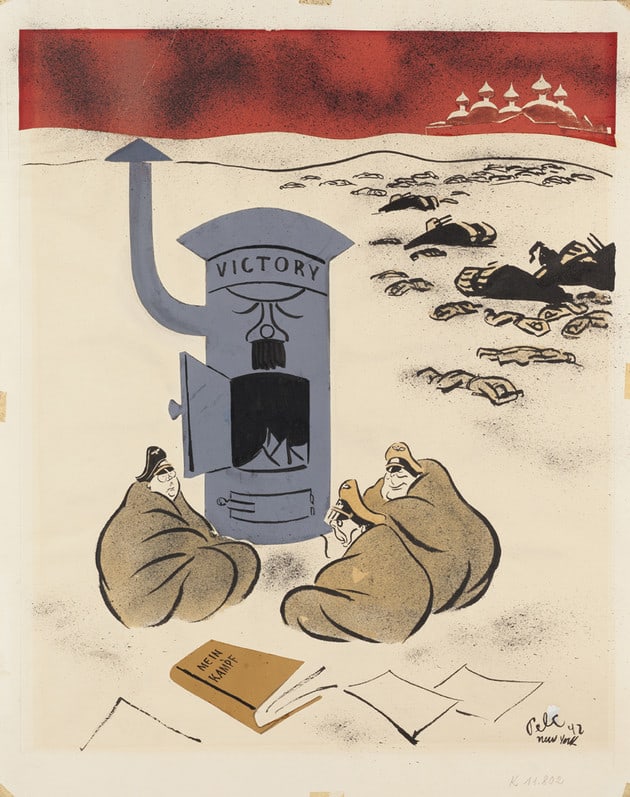

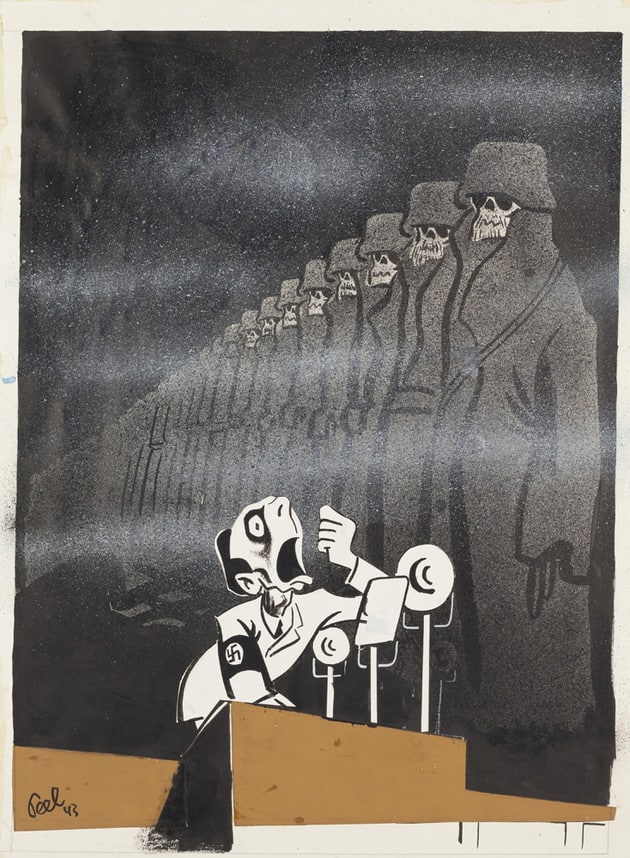

In addition to the drawing Lidice, which was also meant to serve as a model for a poster, Pelc chose to exhibit Russian Campaign (Victory, Victory!), which satirizes the failed campaign of the German troops in Russia. In this drawing, the freezing Nazi commanders, surrounded by fallen soldiers, warm themselves by a stove outside the Moscow fortifications; the stove bears the inscription “Victory,” and the commanders are fueling the fire with pages from Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf. The drawing Stalingrad shows Joseph Goebbels shouting into a microphone, “Wherever the German soldier sets foot, he will remain forever!” as a crowd of skeletons of the soldiers who died in the Battle of Stalingrad line up behind him. Pelc did a variation of this caricature using Hitler, which eventually became better known. There was also a caricature called Goebbels the War Painter in which Pelc employed photomontage, unusual for his work at that time. In it, Goebbels is shown painting the three Axis leaders (Hitler, Benito Mussolini, and Hirohito) who are represented in “all their glory” (Hitler even has a halo) while the three figures, literally bandaged from head to toe, pose for him. Entitled Fact and Fiction (1943), this caricature was reproduced in the February 1944 edition of Free Worldmagazine.8A. T. Peel, Fact and Fiction, in Free World 7, no. 2 (February 1944): 132. At MoMA, he also presented his Kulturträger (Bearer of Culture), in which a German soldier sits by the razed village of Lidice reading Goethe; To be or not to be?, in which Hitler in the role of Hamlet meditates on a mask of Mussolini’s face; as well as The Fist of the Underground, Remember Him?, In the Anteroom of Victory, Mein Kampf, Where Is Hitler?, The Nazi Trigger and Bad Egg. His best-known artworks on display included the drawing Victory Club, in which Joseph Stalin smokes a pipe whose bowl is in the shape of Hitler’s head—while an ashtray in the shape of Mussolini’s head sits on the table in front of Winston Churchill, and Franklin D. Roosevelt’s legs are stretched out on a rug made of Hirohito’s skin. All of the caricatures make strong and clear political messages. As one exhibition reviewer wrote, “Czech artists dip their pens in vitriol.”9“Czech Artists Dip Their Pens in Vitriol,” PM, May 14, 1943. Indeed, Pelc’s caricatures are vivid, dynamic, and persuasive.

Hoffmeister´s Mordant Humor

While Pelc incorporated diagonals and spatial depth, Hoffmeister’s drawings are more planar and subtle, as seen in the documentary photographs of the exhibition War Caricatures by Hoffmeister and Peel. Hoffmeister’s major weapon in his frontal assault on Hitler and the Nazi leader’s allies was his humor. As one critic in the New York Magazine wrote in reaction to the exhibition: “Hitler has conquered Czechoslovakia, but he cannot silence her. She fights back with every weapon in her armory and not the least of these is humor.”10“The War of Ridicule,” New York Magazine, May 23, 1943.

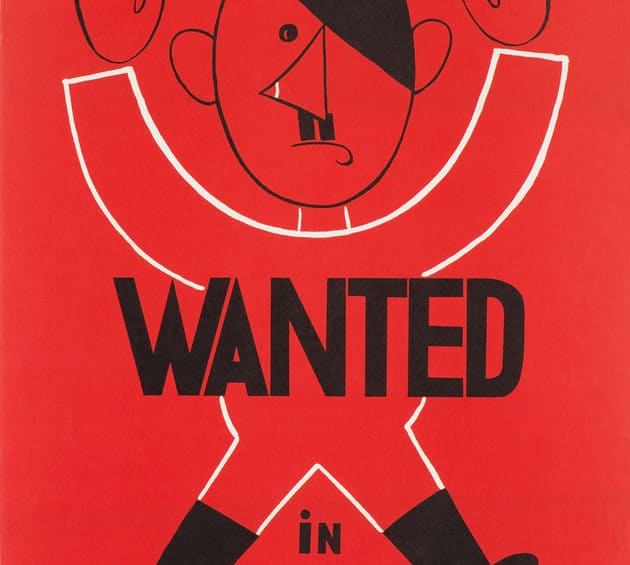

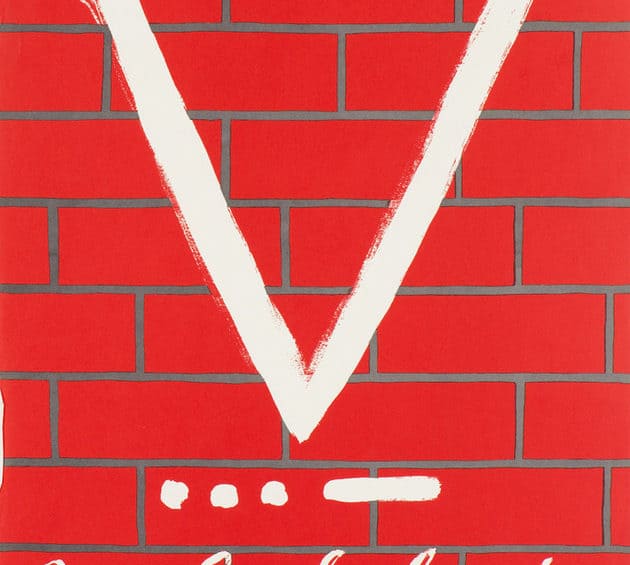

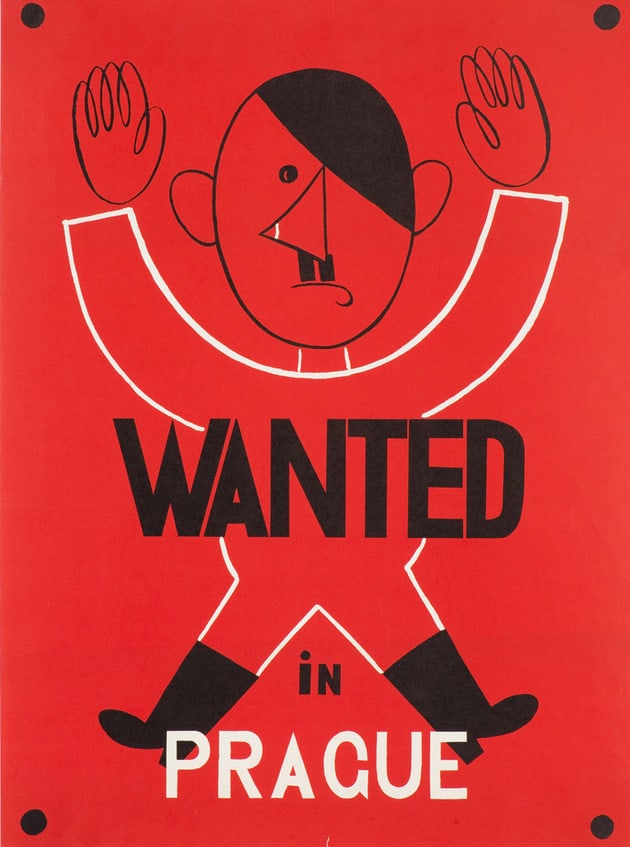

At MoMA, Hoffmeister displayed two posters that had served to decorate the Czechoslovak allegorical float that he, Ladislav Sutnar, and Pelc designed for the “New York at War” parade, organized by City Hall and various civilian and military authorities, on Saturday, June 13, 1942.11For Sutnar’s activities in the United States, see Jindřich Toman, “‘Nesmírně zajímavá motanice’: Ladislav Sutnar a jeho Amerika,” in Ladislav Sutnar—Prague—New York—Design in Action, ed. Iva Janáková (Prague: UPM, 2003): 330–37. As a demonstration against tyrants and occupiers, the parade along Fifth Avenue included some fifty allegorical floats symbolizing US Allies, military troops, and various American patriotic organizations and other national groups. Apart from the state flag, the cab of the Czechoslovak float was decorated with Hoffmeister’s posters Wanted in Prague and Free Czechoslovakia. The former depicts Hitler as a wanted criminal; the latter follows the “V for Victory” campaign launched by the BBC in the first half of 1941, which promoted the V sign as a symbol of victory over the Nazis.12For more, see Lucie Zadražilová, “Propaganda za protektorátu,” in Konec avantgardy? Od mnichovské dohody ke komunistickému převratu, ed. Hana Rousová (Řevnice: Arbor Vitea, 2011): 171–73. Hoffmeister also composed the song “The Victorious V,” together with actors Voskovec and Werich, who participated in this campaign by recording a literary sketch composed of words beginning with the letter V.

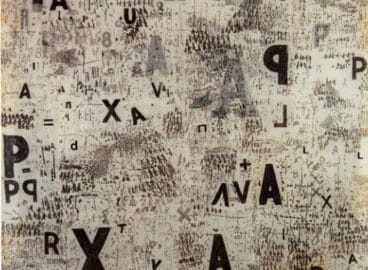

The exhibition also included Hoffmeister’s drawing Vista of Prague, in which a group of curious people approach a skull, in the desert, with a view of Prague Castle in one of its eye sockets, and Their Last Flag showing a group of Nazis in a trench with a white flag of surrender; the other caricatures were The Leader, The March from Egypt, Prisoner from Stalingrad, and Ukraine. Together with these images, Hoffmeister displayed seven “equations” from his Anti-Axis Algebra series in the following order: German Soldier: Red Army Soldier = Cemetery; Sudeten People – Hitler = Headless Mob; Nazi Man + Nazi Woman = Little Nazi; German Soldiers + Death = Peace; Sum of Collaborators [Quisling, Laval, Hácha, Tuka] = Gallows; Japanese Man + Mussolini + Hitler = Convicts, and the best-known among them, Roosevelt + Churchill + Stalin = Victory. Later Hoffmeister claimed that he had made this last drawing on the occasion of the Tehran Conference, at which Roosevelt and Churchill met Stalin, and drew a “smokers’ equation,” in which he symbolized each of them with a smoker’s attribute: Roosevelt is shown as a cigarette, Churchill as a cigar, and Stalin as a pipe. But the Teheran Conference took place in late 1943, while the drawing was displayed at MoMA in June 1943. Hoffmeister thus anticipated the future meeting, whose necessity had been debated long before it actually happened.

Hoffmeister later commented on the selection of works on view at MoMA: “The exhibition was a success. The Americans were not used to such rough humor. All the newspapers wrote about the exhibition and even published examples of the drawings on display.”13Adolf Hoffmeister, Hry a protihry (Games and anti-games) (Prague: Československý spisovatel, 1963): 31. Some of the caricatures displayed actually appeared subsequently in magazines, sometimes in slightly altered form, such as the caricature Victory Club, which was reproduced in late 1943 as a redrawn variant in New-Yorské listy.14New-Yorské listy 70, no. 10 (December 16, 1943): 4. According to Hoffmeister, this exhibition opened the door to some magazine work for the artists: “Antonín Pelc and I drew for whichever [publication] we could, and a set of drawings was gradually coming to life. [. . .] Eventually, we found our way—and that was quite a success—to the Philadelphia Inquirer and then even to The New York Times. That came after our joint exhibition in New York City.”15Adolf Hoffmeister, Hry a protihry: 29. American reviewers agreed the drawings had “a vitriolic and mordant character” and that Hoffmeister and Peel came “savagely and wittily and often very strikingly to grips with current or recent war developments in Europe.”16“Musem of Modern Art,” The New York Times, May 12, 1943.

The Museum of Modern Art itself, in its press release for the exhibition, described the drawings as follows: “These forty cartoons constitute a savagely brilliant attack on the Axis partners, principally the Nazis, impaling them on barbs of ridicule. Unusually interesting technically as well as aesthetically superior as examples of the art of caricature, these drawings in black and white and color make an effective and timely small exhibition.” After the exhibition closed on June 13, 1943, it traveled to various venues in the United States and Canada, including the Addison Gallery of American Art in Andover, Massachusetts, and the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, until August 1944.17Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover, MA, September 10–October 4, 1943; The National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, October 28–November 21, 1943; New England School Group, Andover, MA, December 6, 1943–May 13, 1944.

Around the time of Hoffmeister and Pelc’s exhibiton, MoMA also presented World War II posters and cartoons by Soviet artists who portrayed similiar sentiments, such as Boris Yefimov, Lev Grigorievich Brodaty, Aminadav Moiseevich Kanevsky, Vitalii Nikolaevich Goriaev, and the Kukryniksy group.18War Posters and Cartoons of the USSR_, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, May 1–June 13, 1943. Together, these works constitute an important moment in history, when antiwar and anti-Fascist manifestations where made visible not only at MoMA but also in New York City at large, which welcomed more than just artists from Czechoslovakia seeking refuge during and after World War II.

This is the second part of a two-part essay by Anna Pravdová on the artists Adolf Hoffmeister and Antonín Pelc at MoMA. You can read the first part here.

- 1Hoffmeister recalls this meeting in his book Americké houpačky (American swings) (Prague: ELK, 1937): 173–74.

- 2Adolf Hoffmeister, “Dadamonteur John Heartfield,” in Čas se nevrací (Time never goes back) (Prague: Československý spisovatel, 1965): 188.

- 3Beneš arrived in the United States on May 7 and stayed for one month. He visited New York City several times during his stay, but didn’t see the exhibition until May 20, as corroborated by contemporary press reports. See, among others, “President Beneš v Museum of Modern Art a mezi průmyslníky,” Nedělní New-Yorské listy 53, no. 23 (May 23, 1943): 3.

- 4See for example Stanislav Budín, Věrni zůstali(They stayed faithful) (Prague: Orbis, 1947), 122–33.

- 5The poets included, among others, Edna St. Vincent Millay, William Rose Benét, Joseph Auslander, and Roderick Ginsburg.

- 6For example, Hangmen Also Die! (about the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich and what followed), The Silent Village, Hitler’s Madman, and several others.

- 7Lidice Lives On,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 22, 1942.

- 8A. T. Peel, Fact and Fiction, in Free World 7, no. 2 (February 1944): 132.

- 9“Czech Artists Dip Their Pens in Vitriol,” PM, May 14, 1943.

- 10“The War of Ridicule,” New York Magazine, May 23, 1943.

- 11For Sutnar’s activities in the United States, see Jindřich Toman, “‘Nesmírně zajímavá motanice’: Ladislav Sutnar a jeho Amerika,” in Ladislav Sutnar—Prague—New York—Design in Action, ed. Iva Janáková (Prague: UPM, 2003): 330–37.

- 12For more, see Lucie Zadražilová, “Propaganda za protektorátu,” in Konec avantgardy? Od mnichovské dohody ke komunistickému převratu, ed. Hana Rousová (Řevnice: Arbor Vitea, 2011): 171–73.

- 13Adolf Hoffmeister, Hry a protihry (Games and anti-games) (Prague: Československý spisovatel, 1963): 31.

- 14New-Yorské listy 70, no. 10 (December 16, 1943): 4.

- 15Adolf Hoffmeister, Hry a protihry: 29.

- 16“Musem of Modern Art,” The New York Times, May 12, 1943.

- 17Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover, MA, September 10–October 4, 1943; The National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, October 28–November 21, 1943; New England School Group, Andover, MA, December 6, 1943–May 13, 1944.

- 18War Posters and Cartoons of the USSR_, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, May 1–June 13, 1943.