The names, cultures, and nationalities of African artists who influenced Picasso have historically been omitted from scholarship. Yet Picasso’s interest in African masks is well-known. In this essay, MoMA staff member Kunbi Oni charts the implications— and possibilities—that closer attention to the makers of such masks could shed on modern art.

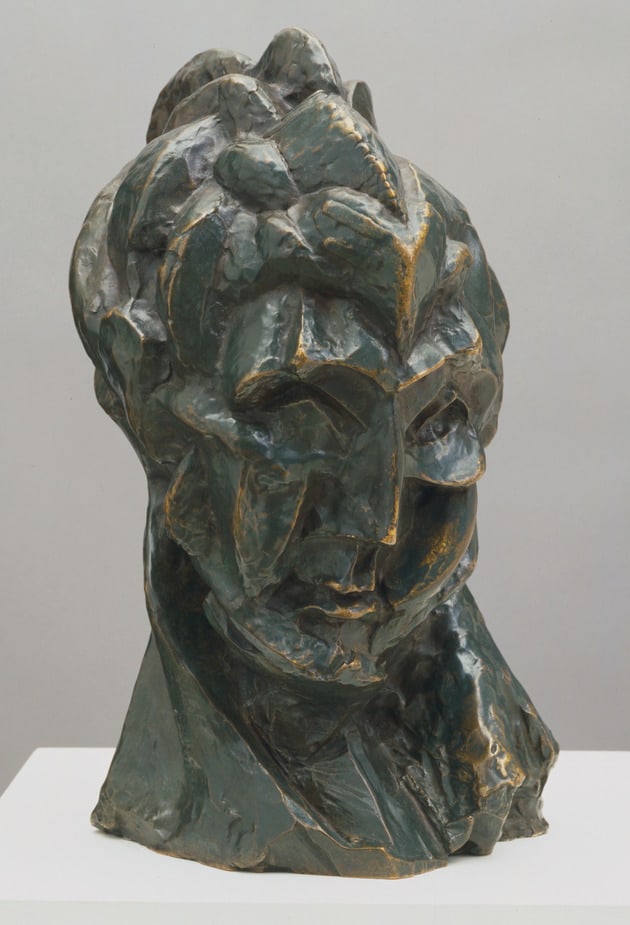

It is well established that in 1907 Pablo Picasso came across a variety of African masks and other African objects in different contexts but settled on the Trocadero Ethnography Museum (now the Musée de l’Homme) as his primary resource.1Alfred Barr, ed., Picasso: Forty Years of His Art (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1939), 60. Encountering these objects would precipitate his “Africa Period,” the time between 1907 and 1909 when his investigation and analysis of the African mask and figure would lead to the dissection of form in his painting and sculpture, and to the flattened curves and planes characteristic of works such as Woman’s Head (Fernande). Together with his contemporaries, he revolutionized Western artistic practice with this shift, heralding the avant-garde. The Trocadero opened in 1882 with displays of both ancient and contemporary African objects, most from the French colonies in Africa. As is reflected in the institution’s own description of its first period, little thought was given to these objects as being the result of artistic production: “Between the lack of funds and the inflow of new objects from the colonies, and despite the best of intentions, the museum had begun to look like nothing more than a giant curiosity cabinet.”2“The Trocadero Ethnography Museum: 1882–1936,” Musée de l’Homme website, accessed February 6, 2018, http://www.museedelhomme.fr/en/museum/history-musee-homme/trocadero-ethnography-museum-1882- 1936.

Similarly, in MoMA’s 1984–85 exhibition “Primitivism” in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern slightly more than a century later, William Rubin explains that Primitivism is “anchored in tribal (rather than exotic court) objects—heretofore considered just curiosities—and involved an appreciation of both their affective ‘magical’ force and their plasticity.”3William Rubin, Primitivism in 20th Century Modern Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1984), 242. And he goes on to maintain an attitude of a singular cultural focus:4This attitude was heavily critized in Thomas McEvilley’s review of the exhibition in Artforum. In his wide-ranging challenge to the premise of the exhibition, he appeals for an evolved perception of the primitive works: “After fifty years of living with the dynamic relationship between primitive and Modern objects, are we not ready yet to begin to understand the real intentions of the native traditions, to let those silenced cultures speak to us at last? An investigation that really did so would show us immensely more about the possibilities of life that Picasso and others vaguely sensed and were attracted to than does this endless discussion of the spiritual propinquity of usages of parallel lines. It would show us more about the ‘world-historical’ importance of the relationship between primitive and Modern and their ability to relate to one another without autistic self-absorption.” Thomas McEvilley, “Doctor Lawyer Indian Chief: ‘Primitivism’ in 20th Century Art at the Museum of Modern Art in 1984,” Artforum 23 (November 1984): 54. “I want to understand the Primitive sculptures in terms of the Western context in which modern artists ‘discovered’ them.”5Rubin, Primitivism in 20th Century Modern Art, 1. Today, more than three decades later, we are more than ready to reconsider how we engage with the twentieth-century “traditional” African objects embedded within the modernist narrative.6The article “Fauve Masks: Rethinking Modern ‘Primitivist’ Uses of African and Oceanic Art, 1905-8,” Joshua Cohen’s treatise on Fauve artists and their relationship to African and Oceanic art, offers an in-depth investigation of how the Fauves and later Picasso understood the objects. Cohen concludes that since the African objects were outside of their own known chronology and understanding of how [Western] art evolved, they could only relate to them through form. Today, however, he contends, as the current lexicon of art history now has scholarship that fully understands African objects, we should expect that exhibitions that revisit the primitivism idea—for example 2017’s Picasso Primitif (Musee du Quai Branly–Jacques Chirac, Paris)—should interrogate the African objects gathered as opposed to simply showing a broader scope of classification. Joshua I. Cohen, “Fauve Masks: Rethinking Modern ‘Primitivist’ Uses of African and Oceanic Art, 1905–8,’ The Art Bulletin 99, no. 2 (June 2017): 136–65.

In the Museum’s 2015–16 exhibition Picasso: Sculpture, Picasso’s status as a self- taught sculptor is emphasized.7“From a twenty-first century viewpoint, these works in their original form have a startling contemporaneity. Their unalloyed enthusiasm for the banal and seemingly amateurish assembly resonate closely with a present-day attraction to humble materials, ordinary objects and technical approaches that show no evidence of skilled training.” Anne Temkin and Anne Umland, with Virginie Perdrisot, Luise Mahler, and Nancy Lim, Picasso: Sculpture (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2015), 26. By likening his practice to that of the self-taught artist—or, by extension, artists not academically trained, such as the traditional African artists—we increase the number of shared attributes between artists and can more readily think of them as closely aligned. If we can commit to this way of thinking, then we can perhaps continue by identifying the artists who emboldened Picasso to “break all the rules,” by name, culture, or country of origin as is the standard.8Augustus Casely-Hayford, “Way of Being: Some Reflections on the Sainsbury African Galleries,” Journal of Museum Ethnography, no.14, Papers Originating from MEG Conference 2001: Transformations, The Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford (March 2002): 120–21. Paul Gauguin was the harbinger of Picasso’s transformation, and subsequently Umberto Boccioni named Picasso as the main influence for his own sculptures of 1913.9Temkin and Umland, Picasso: Sculpture, 14. And these three artists are further tied to both past and more recent histories, connections not afforded traditional African artists. We know that “none of the African pieces Picasso saw in his first few years of fascination with ‘art nègre’ were more than just decades old,”10Rubin, Primitivism in 20th Century Modern Art, 243. and that they came from a set of cultures11“Taken together, the Kota and Hongwe reliquary figures—certainly the most abstract of the tribal sculptures Picasso encountered—constitute, along with Baga figures, and Fang masks, and reliquary heads, the most important African prototypes for his art from June 1907 until the summer of the following year.” Ibid., 266. in the region of West Africa.12Kota in Gabon, Baga and Fang in Guinea, and Baule in Ivory Coast. These details are readily available.13Charles Gore, “Masks and Modernities,” African Arts 41, no. 4 (Winter 2008): 6, www.jstor.org/stable/20447912. The added benefit of specificity is that it allows us to begin to chip away at the idea of Africa as monolithic, and to understand that traditional African sculpture encompasses different forms and types. Applying this small detail makes it possible to deepen our scholarship and to broaden our scope—and thus, potentially, to provide us with a new way of telling the story of modernism and to offer more accurate ways of seeing and developing new audiences.

- 1Alfred Barr, ed., Picasso: Forty Years of His Art (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1939), 60.

- 2“The Trocadero Ethnography Museum: 1882–1936,” Musée de l’Homme website, accessed February 6, 2018, http://www.museedelhomme.fr/en/museum/history-musee-homme/trocadero-ethnography-museum-1882- 1936.

- 3William Rubin, Primitivism in 20th Century Modern Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1984), 242.

- 4This attitude was heavily critized in Thomas McEvilley’s review of the exhibition in Artforum. In his wide-ranging challenge to the premise of the exhibition, he appeals for an evolved perception of the primitive works: “After fifty years of living with the dynamic relationship between primitive and Modern objects, are we not ready yet to begin to understand the real intentions of the native traditions, to let those silenced cultures speak to us at last? An investigation that really did so would show us immensely more about the possibilities of life that Picasso and others vaguely sensed and were attracted to than does this endless discussion of the spiritual propinquity of usages of parallel lines. It would show us more about the ‘world-historical’ importance of the relationship between primitive and Modern and their ability to relate to one another without autistic self-absorption.” Thomas McEvilley, “Doctor Lawyer Indian Chief: ‘Primitivism’ in 20th Century Art at the Museum of Modern Art in 1984,” Artforum 23 (November 1984): 54.

- 5Rubin, Primitivism in 20th Century Modern Art, 1.

- 6The article “Fauve Masks: Rethinking Modern ‘Primitivist’ Uses of African and Oceanic Art, 1905-8,” Joshua Cohen’s treatise on Fauve artists and their relationship to African and Oceanic art, offers an in-depth investigation of how the Fauves and later Picasso understood the objects. Cohen concludes that since the African objects were outside of their own known chronology and understanding of how [Western] art evolved, they could only relate to them through form. Today, however, he contends, as the current lexicon of art history now has scholarship that fully understands African objects, we should expect that exhibitions that revisit the primitivism idea—for example 2017’s Picasso Primitif (Musee du Quai Branly–Jacques Chirac, Paris)—should interrogate the African objects gathered as opposed to simply showing a broader scope of classification. Joshua I. Cohen, “Fauve Masks: Rethinking Modern ‘Primitivist’ Uses of African and Oceanic Art, 1905–8,’ The Art Bulletin 99, no. 2 (June 2017): 136–65.

- 7“From a twenty-first century viewpoint, these works in their original form have a startling contemporaneity. Their unalloyed enthusiasm for the banal and seemingly amateurish assembly resonate closely with a present-day attraction to humble materials, ordinary objects and technical approaches that show no evidence of skilled training.” Anne Temkin and Anne Umland, with Virginie Perdrisot, Luise Mahler, and Nancy Lim, Picasso: Sculpture (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2015), 26.

- 8Augustus Casely-Hayford, “Way of Being: Some Reflections on the Sainsbury African Galleries,” Journal of Museum Ethnography, no.14, Papers Originating from MEG Conference 2001: Transformations, The Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford (March 2002): 120–21.

- 9Temkin and Umland, Picasso: Sculpture, 14.

- 10Rubin, Primitivism in 20th Century Modern Art, 243.

- 11“Taken together, the Kota and Hongwe reliquary figures—certainly the most abstract of the tribal sculptures Picasso encountered—constitute, along with Baga figures, and Fang masks, and reliquary heads, the most important African prototypes for his art from June 1907 until the summer of the following year.” Ibid., 266.

- 12Kota in Gabon, Baga and Fang in Guinea, and Baule in Ivory Coast.

- 13Charles Gore, “Masks and Modernities,” African Arts 41, no. 4 (Winter 2008): 6, www.jstor.org/stable/20447912.