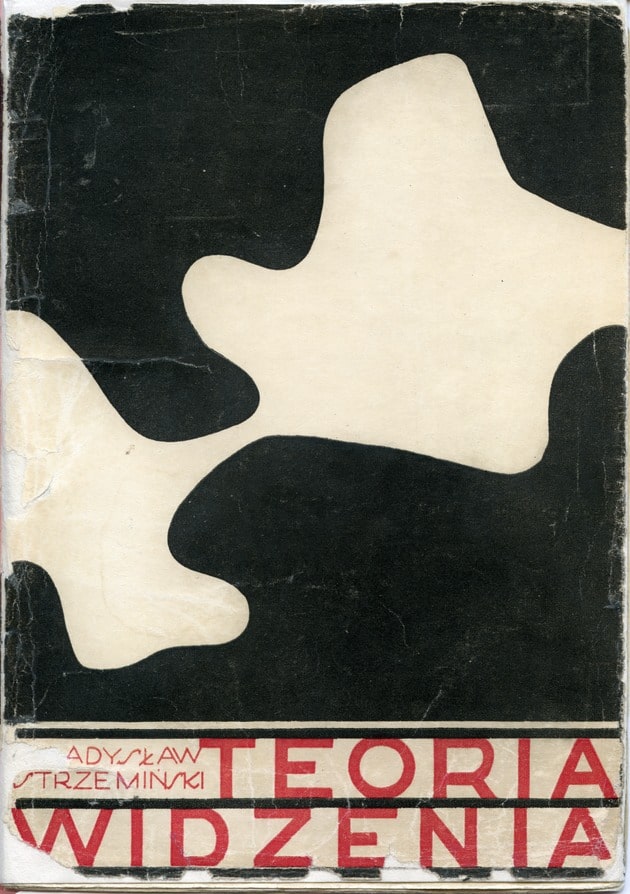

The Polish artist Władysław Strzemiński completed the manuscript for Theory of Vision in 1947, though it was not published until 1958. Nearly fifty years later, a critical re-edition was put out in 2016 by the Museum Sztuki in Łódź, and which this publication on post is glad to promote, and the following excerpt from the book marks a first publication of the text in English. The full text has been translated by Wanda Kemp-Welch and Klara Kemp-Welch, and the excerpt here appears with an introduction by MoMA’s C-MAP Fellow for Central and Eastern Europe, Meghan Forbes.

In the broadest of terms, Theory of Vision, by the Polish artist Władysław Strzemiński (1893–1952), could be described as an expansive overview of centuries of European painting styles. But when it was first published— posthumously in 1958—the poet Julian Przyboś, in a preface to the book, maintains that the texts comprising it do not offer merely a sweeping art historical survey for art students that dictate how they ought to paint. He writes, “[This] is not a painting textbook; it does not teach the reader how to become a painter. The theory teaches an understanding of the evolution of man’s visual consciousness.”1Cited from an unpublished manuscript of the English translation of Władysław Strzemiński, Teoria widzenia, ed. Iwona Luba (Łódź: Muzeum Sztuki, 2016; reprint). English translations by Klara Kemp-Welch and Wanda Kemp- Welch.

Theory of Vision reflects ideas that Strzemiński had been developing and sharing in his lectures for decades, perhaps even as early as 1919 as Iwona Luba suggests in her introduction to a 2016 edition of the book. In that period, Strzemiński was taking classes at Svomos, or the First State Free Art Studios (the predecessor to the better-known Vkhutemas school) in Moscow, and on the staff of the Department of Fine Art (IZO), which had been set up by the newly formed Communist government in Minsk (his birthplace), before he moved to Vilnius.2For more on Strzemiński’s time in Russia and his relationship with Russian artists, see Christina Lodder, “Made in Russia: Strzemiński and the Russian Avant-Garde,” in Powidoki życia: Władysław Strzemiński i prawa dla sztuki/ Afterimages of Life: Władysław Strzemiński and Rights for Art, ed. Jarosław Lubiak (Łódź: Muzeum Sztuki, 2012) and “Katarzyna Kobro and Władysław Strzemiński in Russia,” in Katarzyna Kobro & Władysław Strzemiński: Avant-Garde Prototypes (Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía andŁódź: Muzeum Sztuki, 2017). Kazimir Malevich was on the faculty at Svomas, and would prove to be, famously, both a mentor and an artist against whose ideas Strzemiński formed his own. The younger artist encountered other important figures at Svomas, including Vladimir Tatlin and Aleksandr Rodchenko, and was thus well acquainted with Russian Constructivism. By 1922, however, he came to write “against his Russian colleagues and the entire Soviet experiment,” in his polemic “Notes on Russian Art,” published in the Polish magazine Zwrotnica.3Lodder, “Made in Russia,” 184. Strzemiński is nevertheless strongly associated with the development of Polish Constructivism in the 1920s, which arguably has its roots in its Russian counterpart.

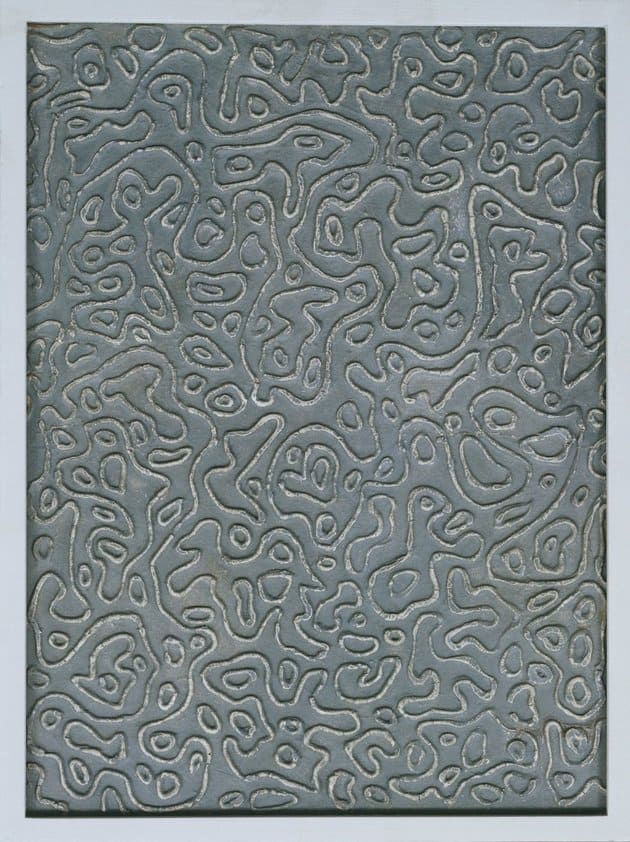

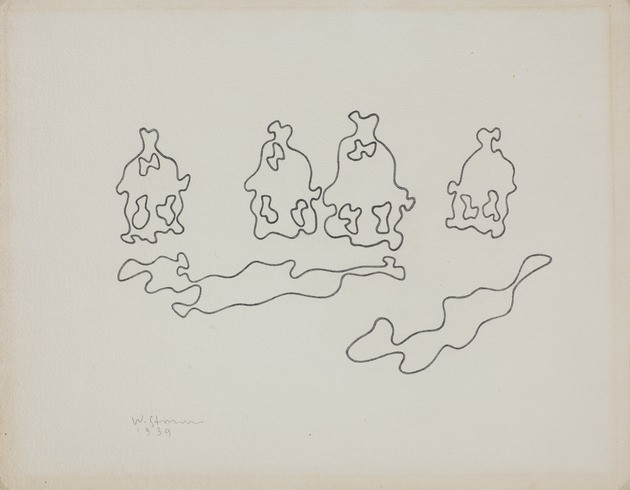

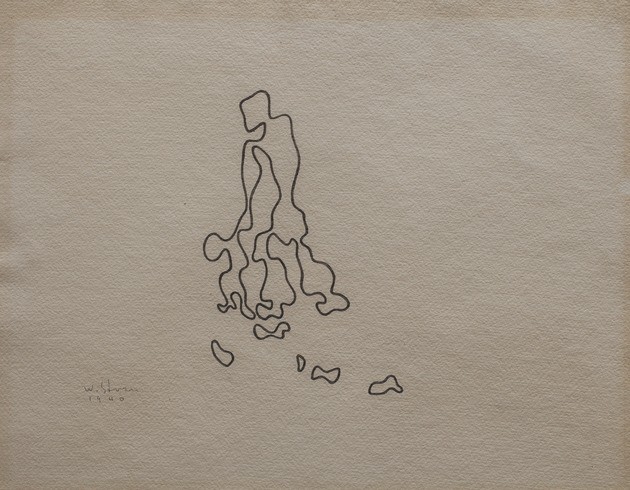

But he is perhaps best known for “Unism,” a theory that insists upon the organicity of an artwork, developed with his fellow artist and wife Katarzyna Kobro. In the November/December 1924 issue of the constructivist magazine Blok—the publishing arm of a group by the same name, which Strzemiński co-founded—he published “B=2; to read . . .,” his last statement printed in the magazine, and his first on Unism, in which he writes, “The law of organic painting requires: the greatest possible union of forms with the plane of the picture.”4Ryszard Stanisławski, Janina Ładnowska, Jacek Ojrzyński, and Janusz Zagrodzki, eds., Constructivism in Poland, 1923–1936: BLOK, Praesens, a.r. [Exhibition] Museum Folkwang, Essen, 12.5.–24.6.1973, trans. Piotr Graff and Ewa Krasińska (Łódź: Muzeum Sztuki, 1973), 82 (emphasis the author’s). Originally published as “B=2, powinno być” in Blok 8–9 (November/December 1924). Strzemiński’s Unist paintings are abstract—though not in the starkly geometric sense of Constructivism—as well as deeply textural. In his Unistic Composition series from the early 1930s, for instance, he created repetitive, hypnotic forms with oil paint applied in high relief. His utopian stance toward his artistic production was distinct from both the mystical elements of Malevich’s Suprematism and the “art into life” philosophy of the Constructivists; rather than positing the role of art as exclusively utilitarian within the context of daily life, Strzemiński wrote, in 1932, that “the social influence of art is indirect.”5Ibid., 111. Originally published as a communication of the “a.r.” group, 1932. While Strzemiński held strongly to the conviction that art was a relevant agent for social change, he also staunchly acknowledged certain formalist dictates; i.e. the “flatness (stemming from the flatness of the stretcher), [and] geometry of forms (stemming from the geometric shape of the canvas)” that would ultimately reflect the negotiation of the artist’s hand with the goods with which he or she works, and thus inherently relate to a greater material-historical context.6Jarosław Suchan, “Kobro and Strzemiński: Protoypes of a New Thinking,” in Avant-Garde Prototypes, 26. Or, as Jarosław Suchan has put it, “the painting constantly reminds the observer of its own material nature, of the fact that it is just an ‘object.’”7Ibid., 32.

Strzemiński completed his Unist Composition series in 1934. Yve-Alain Bois argues that “anti-Unist” statements by Strzemiński and Kobro in texts from 1934–35 suggest that, by then, they had reached an “impasse” that “is more than formal; it is also political, in the broadest sense of the term, and concerns the utopian daydream that was one of Unism’s driving forces as it was of all the movements of the first modernist wave.” He continues, “Strzemiński no longer believed in art’s value as a model, in its role as the herald of a new social reality, because he no longer believed in the possibility of a future Golden Age.”8Yve-Alain Bois, Painting as Model (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990), 131. Also in 1934, at an exhibition in Warsaw, Strzemiński showed none of his Unist, or abstract paintings.9Constructivism in Poland, 1923–1936: BLOK, Praesens, a.r., 28.

Immediately following World War II, Strzemiński began lecturing in Łódź at the State Higher School of the Visual Arts, which he helped found, and Theory of Visionis understood to come largely from the lectures he gave there and broadly reflects the various strains of his theoretical stance toward art production, as briefly outlined above. Besides offering a history of art linked to the biological evolution of the eye, the book reflects the artist grappling with his own art historical narrative, as he attempts to reconcile his earlier work in abstraction in the name of Unism with the politics of the postwar period, in which non-realist works were seen as counter to the socialist project. The language of Theory of Vision is rooted in a Marxist vocabulary of class struggle, which Agnieszka Rejniak-Majewska argues “wasn’t just a facade for Strzemiński.”10Agnieszka Rejniak-Majewska, “A History of the Eye According to Strzemiński,” in Afterimages of Life, trans. Marcin Wawrzyńczak, 284. Rather, she writes, “Marxism offered a number of points coincident—apparently, at least—with Strzemiński’s own political/artistic perspective. They shared the same, dynamic and dialectical, vision of history, an aversion towards ‘formalistic’ art identified with vain aesthetics, and a strong sense of art’s connection with social reality.”11Ibid. But as Rejniak-Majewska also notes, how that last point was envisioned and carried out in the work of Strzemiński differed drastically from the official position of the Communist Party. The consequence of this irreconcilability was stark: the Ministry of Culture removed Strzemiński from his teaching position in 1950, and he died destitute two years later of tuberculosis.

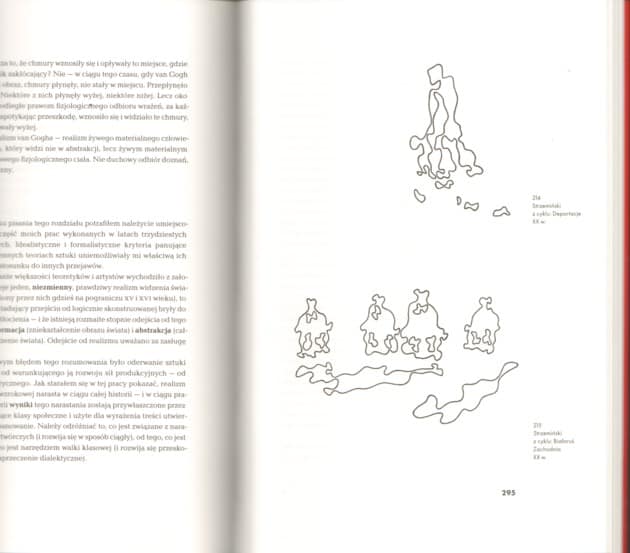

In the final section of Theory of Vision, Strzemiński seeks to justify his abstract art production from the 1930s and 40s, claiming, “When I set about making these works (most of which were burned by the Hitlerites during the Occupation) I subjectively experienced them as being realist and empirical, demanding a far greater degree of observation than paintings considered realist.”12Teoria widzenia, unpublished English-language manuscript. Strzemiński posits a “development of visual consciousness” that evocatively proposes that our mode of and capacity for seeing, and our perceived “image of the world,” are in fact not constant but, rather, subject to economic, political, and social change—the developments in history that likewise shift our perception of reality, and the ways in which we see.13Ibid. Alas, it was apparently not an argument immediately convincing to the Communist Party, and so Theory of Vision would not be published until 1958, six years after its author’s death.

Excerpt from the Introduction to Theory of Vision:

Seeing

Our seeing has not been given to us ready-made and unchanging. Our eye developed from less perfect forms to what we have now as a result of lengthy biological evolution.

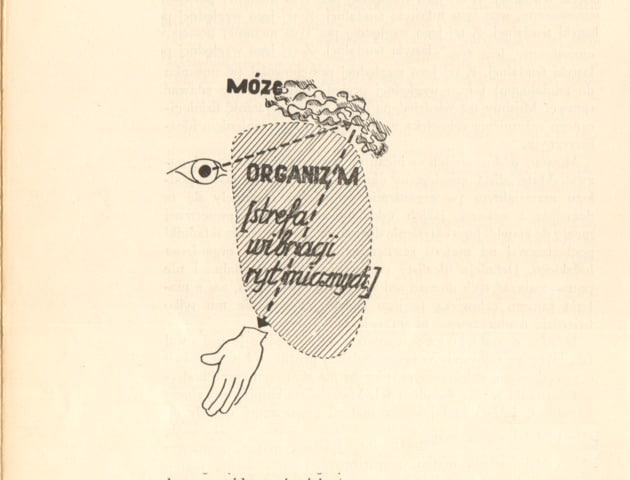

But seeing is not just the passive reception of visual sensations. We analyse the received sensations, confront them with corresponding fragments of reality, make sense of the emergent interrelations and causes: what sort of sensations they are and what they say about the objectively existing world. In addition to the passive, physiological reception of visual sensations, there is the active, cognitive work of our intellect. There is the mutual influence of thinking on seeing and seeing on thinking. Thinking poses questions for seeing to answer. Seeing accumulates a stock of observational material, which is validated and universalised in the process of thinking. Thanks to the constant corrections of thinking in relation to seeing, we are able to make ever better use of received visual sensations. We do not let them slip away, we do not let them pass fruitlessly by, because we recognise what each of them means and to which fragment of reality it corresponds.

There are thus two evolutions in the domain of seeing. One is the evolution of our visual apparatus, the development of the eye, which was at one time – in the simplest forms of life – merely a collection of skin cells more sensitive to light than other skin cells. Passing through a range of models and varieties, it became what it is now – the normal human eye. We know that, in a relatively recent phase of the evolution of the species, the eye could not see colours, that the eye of a mouse, for instance, sees a blurred image of objects, the better to discern movement in their background. There is, thus, biological evolution: the development of seeing through the development of the eye.

Alongside this first process, there is another: the development of skills that make use of seeing. Deduction, on the basis on visual sensations, becomes increasingly precise. Thinking and seeing develop through mutual influence. Their development does not take place in isolation from real, formative living conditions but on a social basis, depending on the needs of the labour process. That is why, by setting new tasks, each successive social system leads to the development of new skills in the use of visual sensations. This is why the second process, unlike the first, biological, one, is historically determined. Just as language developed in relation to successive social systems, so, too, the faculty of seeing, visual consciousness, cannot be formed outside its relation to history, the specific development of the forces of production and the class struggle. In this way, the process of the development of visual consciousness mirrors the process of historical development.

If man sees more than an eagle – even though his eyesight is less sharp – it is because man has a wider range of interests and in effect carries out a wider and more precise analysis of his visual sensations, and because he does not pass over those that would not interest an eagle. That is why man sees less, but his seeing provides him with more information about the world than the dog’s far superior sense of smell, because the correcting function of the human mind takes into account the components of sensations that would be passed over by the dog (e.g. the scent of flowers or chemicals).

Taking as a basis the historical development of visual consciousness, we cannot accept, as idealists do, the existence of a single, timeless, ahistorical image of reality, based on the same visual principles, by virtue of which the eye of every normal man sees reality. It is not the biological reception of visual sensations that determines how the real world is seen, but the co-operation of seeing and thinking – the historically determined development of visual consciousness. It is not the abstract void of “normal” seeing, but the ever-developing historical, concrete fact of visual consciousness.

Seeing is not only the passive, biological act of receiving visual sensations, it is not a purely mechanical reflection of the world, forever the same and unchangeable – like a mirror image. We acquire knowledge of the world not by merely seeing it but by thinking and recognizing what each visual sensation is telling us and which fragment of our knowledge of the world our eye is delivering – in a word, by analysing visual sensations, generalizing and repeatedly testing them. The scope of our seeing is determined not by some “natural,” “normal” seeing, but by the mutually related and interdependent processes occurring between biological seeing and our thinking. It is in this way that visual consciousness arises, which determines the number of components of the world our eye has perceived.

It is not what the eye catches mechanically that matters in the process of seeing, but the consciousness man has of his seeing. Increased visual consciousness is thus a reflection of the process of human development.

So-called professional visual competence is simply one form of visual consciousness. The eye of the experienced textile worker will notice ten times more faults in the fabric than the equally (biologically) able eye of someone of another trade. But that same eye of the textile worker will see nothing when before faced with a cornfield – will not be able to say anything about the humidity of the earth, the ripeness of the corn, the transpiration of the air, or the quality of the soil.

The mechanical visual sensations are in all three cases the same, but the scope of seeing is different. This is because, guided by thinking, eyesight has been attuned to the reception of sensations that it passes over in other cases. The range and quantity of what is seen is determined by visual consciousness as formed by real conditions of existence. Not some “normal,” arithmetically average, abstracted seeing, but seeing shaped by existence and determined by the socio-historical structure.

Realism – The Image of Reality

Idealist aesthetics has recourse to concepts of unchanging, “eternal” nature, and of a preconceived, unchanging, ahistorical man with a preconceived, unchangeable, “eternal” way of seeing nature. It occasionally lays aside this “eternal” seeing in favour of pragmatic “normal’” average seeing. In both cases, it insists on the unchanging, constant, ahistorical seeing of unchanging nature.

Taking into consideration only the apparatus of seeing and not taking account the directing and organizing role of thinking and experience, it concludes that we see a constant, unchanging, invariable image of the world from which we receive an unchanging fixed quantity of constant visual sensations.

It may be the case that seeing has not changed for a long time, that the mechanism of the eye’s functioning remains the same as it did several thousand years ago. But what matters to us is not what the eye grasps mechanically, but the consciousness man has of his seeing. He has only really seen what he is aware of having seen. The rest remains unrecognized beyond his consciousness and therefore goes unnoticed. Experience shows that we notice only the phenomena in nature upon which we focus our attention. It is as though our thinking poses in advance the questions to which our eyesight is to provide answers. The range of observation to which, by seeing, we are to provide an answer either confirming our previous assumptions or contradicting them, is marked out. The labour of thinking, in co-operation with the direct activity of seeing, is decisive for the wealth and diversity of our observations.

That is why the image of nature is not one and the same always and for everyone. Its limits are decided by the historically determined development of visual consciousness. Idealist aesthetics formulated the object, reality, sensations solely in terms of the object, and not as a human activity and practice – not subjectively. That is why it referred to the image of the world (constant and unchanging) rather than to human cognitive activity, intent upon an ever more complete understanding of this image. Nature was referred to as to something given once and for all and absolutely unchanging, whereas there was no discussion of the human activity of seeing and the socio-historical process of the development of visual consciousness and of coming to understand nature. Only when we consider seeing in its developmental dynamics, in its dialectical unity with thinking – can we understand that the image of the world is subject to change and development and is comprised in our visual consciousness.

The image of nature “as it is,” arises only from the conscious components of seeing. The unconscious components go unnoticed, are treated as an obstacle, an imperfection in seeing, a distortion of the real world and of real, not illusory, objective nature. Not subjected to the thinking process – they have failed to disclose the truth about reality (inherent to them) and were therefore rejected as marginal.

Thus, we distinguish between seeing (in the biological sense) and theconsciousness of seeing. In so far as the former is dependent on slow biological evolution and presumably remains unchanged for long periods of time, the latter develops over the course of history. Man’s ability to make use of his seeing develops and the quantity of consciously seen visual phenomena increases. The image of the world seen by man changes and develops. The process of the development of visual consciousness is a historical process, historically conditioned by the demands of socially determined processes of labour in different successive historical systems. Thus, the image of the world that we see through our real visual consciousness is not unchangeable, not the only “true” reality, given once and for all, in some abstract void outside history, but a changeable image, dependent on historical development, on social systems arising in its course and, ultimately, on the class struggle shaping history. Visual consciousness develops in active periods of history and remains unchanged in periods of stabilization or even regresses with the regression of historical and cultural structures. The expanding base of visual consciousness constitutes the essential foundation for the development and transformation of our knowledge about the world. This is how we see the world – not biologically, but historically. We see realistically – with our real, conscious eyes.

The idealist aesthetic deploys one, fixed notion of realism, one that does not capture the changeable essence of our seeing. It does not see realism as having been formed through the process of human seeing’s protracted cognitive work, or as the result of man’s work moving towards an increasingly deeper knowledge of truth, but as a given, once and for all, as binding for all times. One historical stage of realism is, in this case, taken for realism’s absolute.

Conceiving of realism in relation to human activity, seeing it as being the outcome of a development in visual consciousness, we must, in practice, acknowledge its infinite possibility of development. Every genuine, conscious visual sensation contributes a new element of knowledge about the world and enriches the domain of realism that has hitherto existed. Thus, in speaking of the historical process of the development of realism, we should, in each concrete instance, define the visual sensations on the basis of which it emerged and the scope of the visual consciousness that shaped it.

Realism is not a Platonic metaphysical absolute but the historically evolving process of the development of the human cognitive faculty.

- 1Cited from an unpublished manuscript of the English translation of Władysław Strzemiński, Teoria widzenia, ed. Iwona Luba (Łódź: Muzeum Sztuki, 2016; reprint). English translations by Klara Kemp-Welch and Wanda Kemp- Welch.

- 2For more on Strzemiński’s time in Russia and his relationship with Russian artists, see Christina Lodder, “Made in Russia: Strzemiński and the Russian Avant-Garde,” in Powidoki życia: Władysław Strzemiński i prawa dla sztuki/ Afterimages of Life: Władysław Strzemiński and Rights for Art, ed. Jarosław Lubiak (Łódź: Muzeum Sztuki, 2012) and “Katarzyna Kobro and Władysław Strzemiński in Russia,” in Katarzyna Kobro & Władysław Strzemiński: Avant-Garde Prototypes (Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía andŁódź: Muzeum Sztuki, 2017).

- 3Lodder, “Made in Russia,” 184.

- 4Ryszard Stanisławski, Janina Ładnowska, Jacek Ojrzyński, and Janusz Zagrodzki, eds., Constructivism in Poland, 1923–1936: BLOK, Praesens, a.r. [Exhibition] Museum Folkwang, Essen, 12.5.–24.6.1973, trans. Piotr Graff and Ewa Krasińska (Łódź: Muzeum Sztuki, 1973), 82 (emphasis the author’s). Originally published as “B=2, powinno być” in Blok 8–9 (November/December 1924).

- 5Ibid., 111. Originally published as a communication of the “a.r.” group, 1932.

- 6Jarosław Suchan, “Kobro and Strzemiński: Protoypes of a New Thinking,” in Avant-Garde Prototypes, 26.

- 7Ibid., 32.

- 8Yve-Alain Bois, Painting as Model (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990), 131.

- 9Constructivism in Poland, 1923–1936: BLOK, Praesens, a.r., 28.

- 10Agnieszka Rejniak-Majewska, “A History of the Eye According to Strzemiński,” in Afterimages of Life, trans. Marcin Wawrzyńczak, 284.

- 11Ibid.

- 12Teoria widzenia, unpublished English-language manuscript.

- 13Ibid.