If the Caribbean has largely been subtracted from those better-known narratives of art and artists that dominate the Atlantic world, attempts to mend this failing have often brought about mixed results. How may we come to appreciate that Caribbean experience is integral to the historical development and understanding of modern and contemporary art? What guarantees are there that applying the terms transnational and provincial offers a robust means for writing and curating more inclusive, open (and even global) histories of art that do justice to the Caribbean? As Leon Wainwright suggests in this brief comment, even after such deliberate effort, some older tendencies in thinking about art of the twentieth century persist, returning to haunt us.

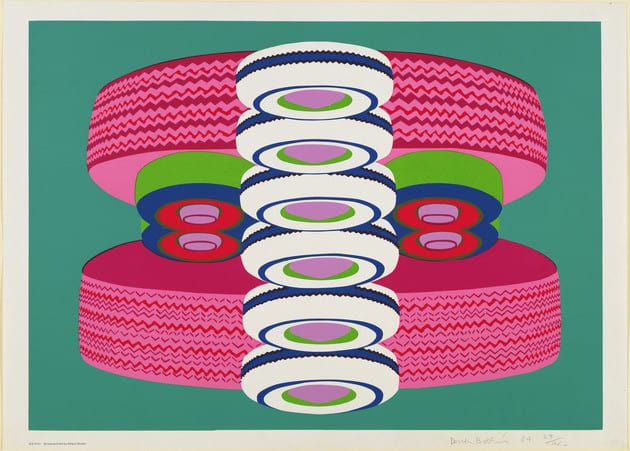

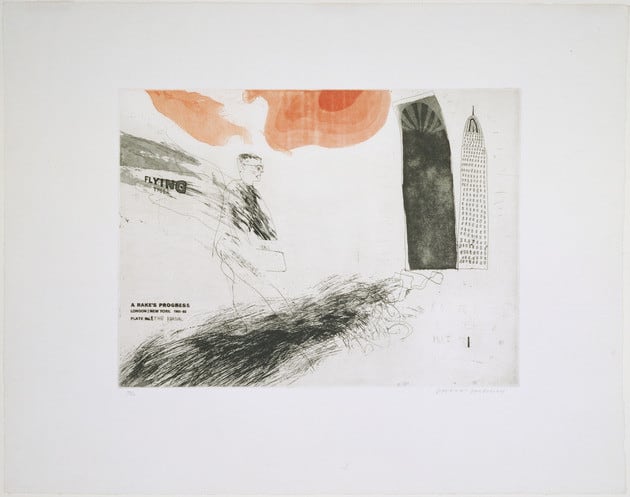

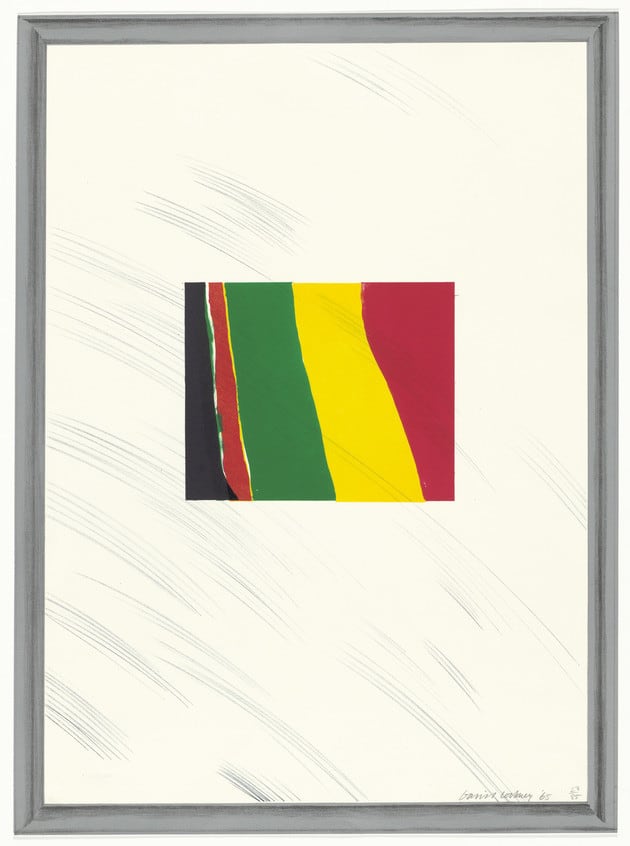

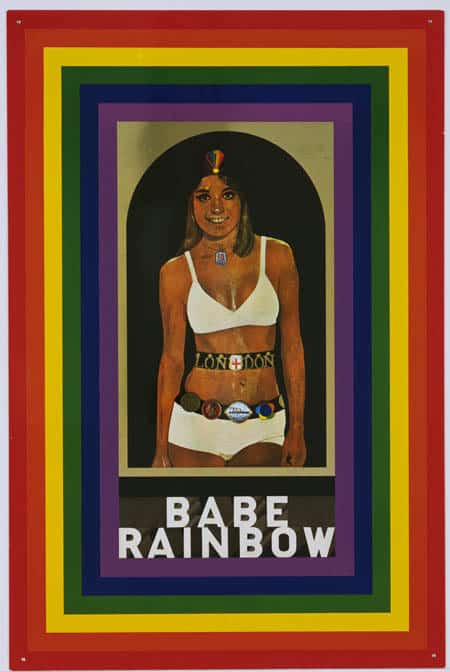

Take the example of an artist such as Frank Bowling (b. 1934), whose multiple migrations across the Atlantic, between Britain and the United States, and the matter of his birth and upbringing in what was then British Guiana, prompt the need for a purposefully transnational account of modernism and a debate about what counts as “provincial.” Particular scrutiny has been paid to Bowling’s presentation and his reception as an artist during the late 1950s and early 1960s, when he studied at the Royal College of Art in London alongside the soon-to-be canonized figures of British Pop art David Hockney, R. B. Kitaj, Derek Boshier, and Peter Blake.1Leon Wainwright, “Frank Bowling and the Appetite for British Pop,” Third Text, no. 91 (2008): 195–208; Leon Wainwright, Timed Out: Art and the Transnational Caribbean, Rethinking Art’s Histories (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2011); and Leon Wainwright, “Varieties of Provincialism and Belatedness: Decolonisation and British Pop,” Art History 34, no. 4 (2012):442–61. Certainly Bowling and his work met with imputations of being provincial, and he experienced racism and nationalistic attitudes that intensified with the breaking up of the British Empire. Authorities such as art critics were unable to accept that a serious contributor to artistic modernism could hail from the Caribbean. His situation was shared by many other artists active in Britain who had migrated from its colonies or former colonies around the world. What seriously complicated such a vocabulary, however, is that the celebrated Pop artists would try to cultivate an image of themselves as also “provincial.” For these canonical artists, to be self-positioned slightly behind the United States, to be set apart from its latest developments, was to be suitably if not favorably distanced from the “leading” example of modernism centered in New York.

Thus there was provincialism of one sort (the condition of being displaced, marginalized, excluded) and then there was provincialism of another sort, of the ameliorated, recuperated kind. Bowling could barely be the latter. He couldn’t join the privileged few in postwar London—a group largely made up of white artists who trendily capitalized on the associations with an ostensible “outsiderness” and English authenticity, brokered at a safe distance from New York. After a first flush of serious acclaim in London, he began to struggle, the gap widening between his art practice and that of this British art brand. By 1966 he had moved to the United States. And it was there, among artists responsible for an outpouring of creativity that framed debates on art, civil rights, and “race,” that Bowling went on to make a further and lasting contribution.

A Caribbean Artist in the Age of Black Power

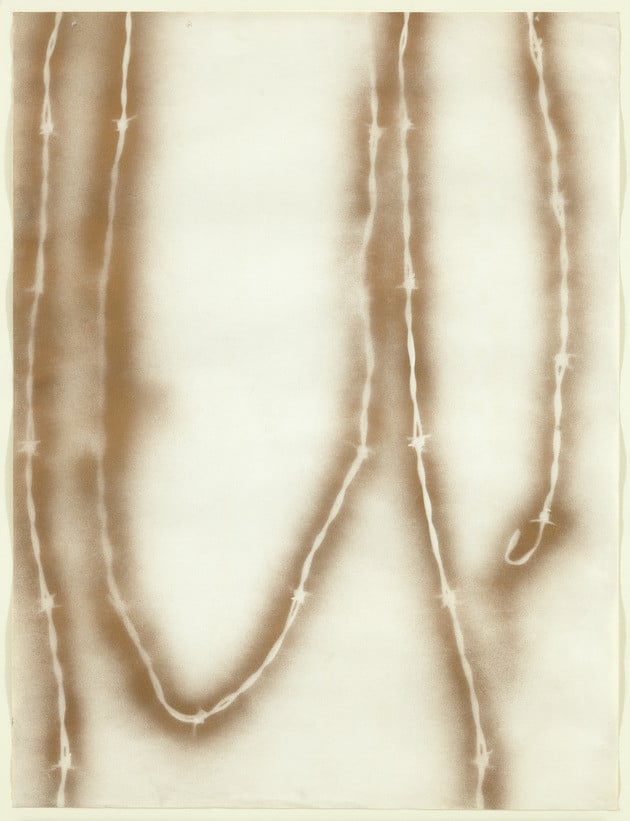

But whenever we are invited to explore Bowling’s art made during his time in America, similar problems of art historical “visibility” and value seem to arise anew. Just as art historians and curators seeking to inscribe Bowling into the British story of Pop have had to grapple with his relegation to the footnotes of dominant art narratives, so too is there a similar need when revising American stories of art since the late 1960s. The recent curatorial presentation of him in the Tate Modern survey exhibition Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power traced twenty years of art by black American artists, from roughly 1963 to 1983. Featuring Bowling’s immense Map Paintings begun in 1967 after his move to the United States, the exhibition made much of works first seen by large audiences at the Whitney Museum of American Art in the 1971 exhibition Contemporary Black Artists in America. The chief curatorial prerogative was to reveal how these canvases bear the qualities of a “black abstraction” as the artist joined a vigorous debate on the role and responsibility of black artists, further evidenced by his published writings of the period.

The impression conveyed by such a presentation at the Tate, explicated in an essay by curator Mark Godfrey,2Mark Godfrey, “Notes on Black Abstraction,” in Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, edited by Mark Godfrey and Zoe Whitley (London: Tate Publishing, 2017), 147–90. is that these canvases have helped us today in making much better sense of American painting of the late 1960s–early 1970s. I do wonder, however, whether this desire to forge a connection to a Caribbean artist and migrant to America does not (once again, and rather despite its aim) put him at a slight distance from the main historical action. We are told that paintings such as Middle Passage (1970) ostensibly carry “expectations that were more literally fulfilled by [Larry] Rivers’s works” and that Bowling’s “strategy relates to the works…by [Melvin] Edwards and [Joe] Overstreet,” which are credited with being “a monument to the strength of those whose ancestors lived through the Middle Passage and survived.”3Godfrey is referring to Melvin Edwards’s Curtain (for William and Peter) (1969); the following paintings from the Joe Overstreet exhibition in Houston, Texas, 1972: Mandala (1970), We Came from There to Get Here (1970), and For Happiness(1970); and Al Loving’s Self-Portrait #23 (1973). Quoted text from Mark Godfrey, “Notes on Black Abstraction,” 177, 178. And pains are taken to clarify that works from among Bowling’s Map Painting series were included at the Whitney in 1971, in the same lobby gallery where Alvin Loving had shown in 1969 and Edwards in 1970.

For an artist and artworks to be “included” in this U.S. story, they seem to undergo a process of codification, if not translation—a process that oversimplifies the whole matter of how to tackle history’s exclusions. Terms that are chosen to compare Bowling and his American contemporaries tend to plot a strict chronological order, in the nature of what may be called an “order of succession.” This treatment qualifies Bowling’s role by way of association with others, yet always by placing him a little outside or slightly behind them. Such is the careful calibration of the emphasis given to Bowling’s bearing on American art.

The underlying problem here is that we are falling into a habit of art historical narration that privileges the United States when the issues and subjectivities under discussion are more complexly transnational. There is nothing remarkable in this except that, on the surface, the stated objective is actually to explode the master narrative by explicit address of the sins and omissions of its exclusions. We find Bowling’s American-made works then become detached from the background of his achievements prior to moving to America, namely his obvious transgression of the figuration-abstraction divide, in which he first engaged in the 1960s, well before his move to New York. Why this goes unacknowledged is at first unclear until we notice that this wider transnational picture offers the grounds for challenging and reversing the order of succession. The American story would be compromised by an unequivocally accepting account of this Caribbean artist’s entry into the curatorial and scholarly record.

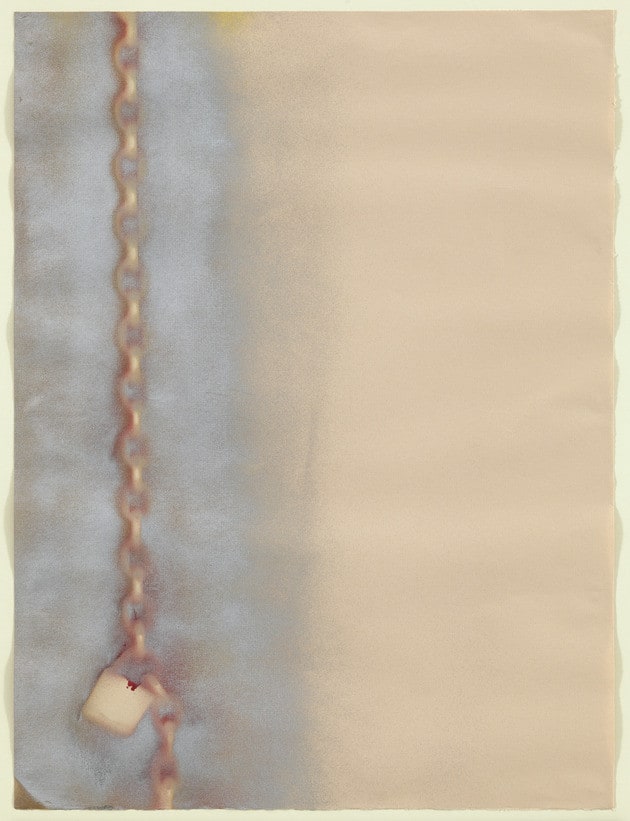

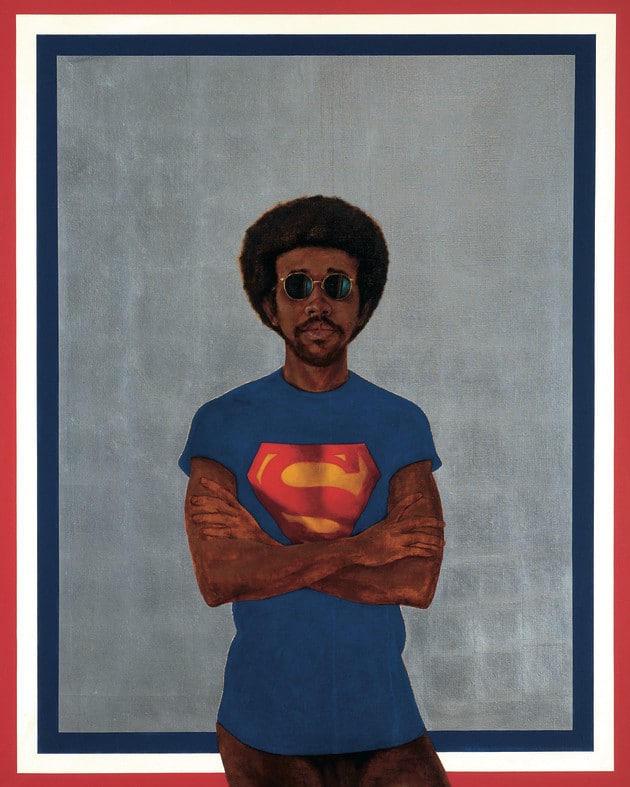

Indeed, many of Bowling’s London-made pieces supply reasons to think differently about the salient directions and debates in American art. We could credibly cast a canvas such as his Cover Girl of 1964–664Frank Bowling, Cover Girl, 1964–66. Acrylic and oil on canvas, 57 x 40 in. (144.8 × 101.6 cm). as a forerunner to much later, better-known works, such as Barkley L. Hendricks’s Icon for My Man Superman (Superman Never Saved any Black People—Bobby Seale) of 1969.5Barkley L. Hendricks, Icon for My Man Superman (Superman Never Saved any Black People—Bobby Seale), 1969. Acrylic, oil, and aluminium leaf on canvas, 59 1/2 x 48 in. (151.1 x 121.9 cm). In this way, a pairing of these paintings unsettles what we may think was particular to American painting at that time. Both works employ a superimposed body, cutting a figure of “self-assured individualism,” as Tate curator Zoe Whitley suggests for the work by Hendricks.6Zoe Whitely, “American Skin: Artists on Black Figuration,” in Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, 194. Yet the image by Bowling, with its twofold female presence—a standing figure interrupting the picture plane beneath a print of his mother’s house—is far differently gendered than any iconic Black Panther male activist/superhero. The works compare on the subtler level of materials and technique. Hendricks’s use of aluminium leaf on canvas gives his work a silvery, reflective surface not unlike Bowling’s earlier use of gold as a generative synecdoche and optical apparatus in his monumental painting Mirror (1964–66).7Frank Bowling, Mirror, 1966. Acrylic and oil on canvas, 120 x 84 in. (304.8 × 213.4 cm). But I am not sure that the work by Hendricks shares much with Bowling’s reflections on fashion photography and the racialized body. Cover Girl queries whether image-making in the commercial field automatically aids the resistive purpose of picturing difference, and so teases apart the issue of how much to trust “popular” imaging at all.

Exploding the Canon Backfires

Recent curatorial comparisons between Bowling and his black contemporaries in the United States are salutary for showing how the presence in America of Bowling and other artists of the black diaspora contends with the canonized art of the age of American “Black Power.” Centrifugal forces in the field of historical representation draw in the wider transnational field of art, implicating artists within a specific nation-narrative structured by the discourse of U.S. race relations. It follows, however, that plotting the journeys of artists such as Bowling within the metropolitan art scenes and domestic cultural landscape of America can easily result in a provincializing gesture of “differential inclusion” within the nation.

Placing an immensely creative individual such as Frank Bowling within a category of black abstraction when that category is thought to be exemplified, if not entirely invented, by American artists alone, is a historiographic gamble. Such uncertainty has often been felt by modern and contemporary artists of the Caribbean at large. Time and again, as curators have broached the roles of Caribbean artists in northern transatlantic histories of art, they have stumbled. When evaluating their efforts to redress the half-told tale of Bowling, whether that be of his time working in Britain or in America, we need to sift and sort through the politics and the means of historical narrativizing.

The contrapuntal, countercultural empowerment narrative about “artists of color” in America, poised to offer a (counter-)canonizing gesture, may at the same time only displace artists of transnational and Caribbean backgrounds. It can diminish the complexity of their experience and provincialize it by failing to connect the dots with any robust degree of equity. The word provincializing is an especially apt one, with its roots in the language of military strategy (from the Latin vincere), suggesting conquered territory, contained at a distance. When art of the United States can be shown to gain its cultural character by virtue of black participation, certain artists are sometimes placed in a counterposition at the very periphery of the American nation. Others are removed altogether and sent back to the geographical littoral from which they came. We hear precious little of the careers had in America by other English-speaking Caribbean-born artists, such as Aubrey Williams, Philip Moore, LeRoy Clarke, Stanley Greaves, Albert Chong, and many, many others.

The discourse rehearsed lately by Tate Modern about the “soul of a nation” was notably all about both the American nation as well as the transnation—that is, the outer-national community of black people everywhere. Although playful in its simultaneity, the effect even so was one of exploiting a notion of “race” that remains both abstract and routed through America, so that black or diaspora transnationalism can still be firmly centered there. Moreover, there is an unmissably temporal dimension to this appropriation of the center, in that the “soul” in question is a historically universal zeitgeist, defining the “age of Black Power.” All other regions of the black diaspora elsewhere in the Atlantic would soon have to “catch up” with America. There is Black Power and then there is American Black Power, and when the two are quietly conflated, “soft” American Power enters through the back door.

Persisting Nation-Narratives

Where there is lived experience in common, spanning the Atlantic divide, exclusive notions of national community come to be tested. This is a fact not limited to the example of Frank Bowling, with his dual appearance in these postwar national art stories (and let’s not overlook that actually he appears in a third, that is, in the nation-narrative of Guyana). Rather, it can be found in the lives and works of many more artists of Caribbean descent during the twentieth century. An unwitting bias toward Americocentrism would render as provincial their experiences of blackness and diaspora as they formed outside the United States—as if the coupling of art and black identification can have one and only one natural “home”—in America. That would buy into the very same mapping of identities that saw Hockney and other canonical figures of British art enjoying their careers as “provincials.” Indeed, we should never assume that the reactionary celebration of provincialism, which emerges from the contest for centrality, was ever much of an option open to artists such as Bowling. Their integral participation in the modern and contemporary art community entailed an experience of provincialism of the hard-felt kind, as a condition of being undervalued and dismissed.

That chain of events cannot be undone or somehow redeemed by choosing to see provincialism everywhere. We should avoid trying to reclaim it as a one-size-fits-all arbiter of value, or even as the marker of a nascent “contemporaneity” for art, liberated from the strictures of art history’s geopolitics (as first suggested by Terry Smith, for example, in his celebrated essay of 1974, “The Provincialism Problem”).8Terry Smith, “The Provincialism Problem,” Artforum 13 (1974):54–55. Such a choice would relativize the term beyond all recognition, betraying deep ignorance about those moments when provincialism became a badge of pride that for some artists was denied—when the provincial and transnational in all their corollaries became an object of near-fetish, of fashion and fascination, with the effects of elevating certain artists while further displacing others.

Consequently, introducing a Caribbean dimension to the story of modernism can have a truly arresting effect on the binaries of visibility and invisibility, the inclusions and exclusions of art and its histories. It reveals the errors of employing a vocabulary without being mindful of its limits, of glossing over the inequalities. There are deep sensitivities surrounding such terms as transnational and provincial, a deep background to their uses, and hence a set of live issues and real challenges when uncovering the hidden relationships between the Caribbean, Britain, and the United States in this complexly entwined transatlantic history.

- 1Leon Wainwright, “Frank Bowling and the Appetite for British Pop,” Third Text, no. 91 (2008): 195–208; Leon Wainwright, Timed Out: Art and the Transnational Caribbean, Rethinking Art’s Histories (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2011); and Leon Wainwright, “Varieties of Provincialism and Belatedness: Decolonisation and British Pop,” Art History 34, no. 4 (2012):442–61.

- 2Mark Godfrey, “Notes on Black Abstraction,” in Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, edited by Mark Godfrey and Zoe Whitley (London: Tate Publishing, 2017), 147–90.

- 3Godfrey is referring to Melvin Edwards’s Curtain (for William and Peter) (1969); the following paintings from the Joe Overstreet exhibition in Houston, Texas, 1972: Mandala (1970), We Came from There to Get Here (1970), and For Happiness(1970); and Al Loving’s Self-Portrait #23 (1973). Quoted text from Mark Godfrey, “Notes on Black Abstraction,” 177, 178.

- 4Frank Bowling, Cover Girl, 1964–66. Acrylic and oil on canvas, 57 x 40 in. (144.8 × 101.6 cm).

- 5Barkley L. Hendricks, Icon for My Man Superman (Superman Never Saved any Black People—Bobby Seale), 1969. Acrylic, oil, and aluminium leaf on canvas, 59 1/2 x 48 in. (151.1 x 121.9 cm).

- 6Zoe Whitely, “American Skin: Artists on Black Figuration,” in Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, 194.

- 7Frank Bowling, Mirror, 1966. Acrylic and oil on canvas, 120 x 84 in. (304.8 × 213.4 cm).

- 8Terry Smith, “The Provincialism Problem,” Artforum 13 (1974):54–55.