Through the acquisition of René Vincent’s 1940 painting Le combat des coqs (Cock Fight), the Museum of Modern Art became the first major art institution abroad to acknowledge the importance of the Indigenist painting movement in Haiti. Through a close analysis of documents in the MoMA Archives, this essay challenges the dominant narrative about the development and internationalization of Haitian art in the 1940s.

The first artwork by a Haitian artist to enter The Museum of Modern Art’s collection did so in September 1944 through the efforts of René d’Harnoncourt (1901–1968), who would go on to direct MoMA from 1949 to 1967. D’Harnoncourt traveled to Haiti at least three times at key moments in the process of the internationalization of Haitian art. The first time was in his role as the general manager of the Indian Arts and Crafts Board of the U.S. Department of the Interior in 1942, shortly before his transition to acting director of the Office for Inter-American Affairs. Then he went to Haiti twice as MoMA’s vice-president in charge of foreign activities.1René d’Harnoncourt to John Marshall, February 13, 1948. René d’Harnoncourt Papers, II.16, Archives of The Museum of Modern Art. As a curator and arts administrator, he specialized in indigenous art and ethnographic objects and developed large exhibitions of Mexican and Native American art. During his 1942 trip, he admired an exhibition of Haitian archaeological and ethnographic objects as he expressed in a letter to his host at the recently formed Bureau d’ethnologie.2René d’Harnoncourt to Edmond Mangonès, December 15, 1943. René d’Harnoncourt Papers, II.16, Archives of The Museum of Modern Art. The Bureau was formed in 1941 and organized exhibitions. He also met the American watercolorist DeWitt Peters (1902–1966), a conscientious objector who was teaching English in Haiti in lieu of serving in the military during World War II. At that time Peters was preparing to open the Centre d’Art, an art school and exhibition space in Port-au-Prince that he would inaugurate in 1944. Through Peters, d’Harnoncourt purchased René Vincent’s 1940 painting Le combat des coqs (Cock Fight)—which he had seen in Haiti—for his private collection and which MoMA acquired from him in September 1944.3After d’Harnoncourt inquired about the painting in a letter dated November 25, 1943, Peters followed up twice regarding d’Harnoncourt’s potential purchase of it—once in December 1943 and again in March 1944. The two then negotiated the price and agreed on $30 plus shipping expenses. DeWitt Peters to René d’Harnoncourt, December 30, 1944; DeWitt Peters to René d’Harnoncourt, March 29, 1944; René d’Harnoncourt to DeWitt Peters, April 9, 1944; DeWitt Peters to René d’Harnoncourt, May 17, 1944; René d’Harnoncourt to DeWitt Peters, May 31, 1944. René d’Harnoncourt Papers, II.16, Archives of The Museum of Modern Art. D’Harnoncourt’s correspondence in the MoMA Archives reveals how he supported numerous important figures in Haitian art history throughout the 1940s, fostering the development of local art institutions and art-making by Haitian practitioners.

The Centre d’Art would become famous for the self-taught artists it promoted, who were so successful that their so-called naïf paintings and sculpture came to define Haitian art for many decades to follow. The myth perpetuated by foreign critics and collectors, beginning in 1947 with André Breton (1896–1966) and continuing with writer Selden Rodman (1909–2002), was that the Centre d’Art was the starting point for Haitian fine art.4Breton promoted the painter Hector Hyppolite in particular, and dedicated a short chapter to him in his book. André Breton, Le surréalisme et la peinture (Paris: Gallimard, 1965), 308-312. Peters was certainly aware of an existing tradition of Indigenist art—which began as a literary movement to express nationalist pride by conveying rural, indigenous aspects of Haitian culture in artistic form—but he was dismissive of any success that Haitian artists had achieved prior to the opening of the Centre d’Art.5Gérald Alexis, “Il Y a Quarante Ans, S’ouvrait Pour L’épanouissement de l’art Haïtien,” Le Nouvelliste, May 3, 1984. Because of the implementation of his Western-centric education and exhibition program, Peters believed that the Centre would turn Haitian “primitives or popular painters” into artists who “very soon will produce very remarkable works” as the Centre would “stimulate [them] to do better work.”6DeWitt Peters to Monroe Wheeler, January 17, 1945; DeWitt Peters to Luis de Zulueta Jr., February 13, 1945. René d’Harnoncourt Papers, II.16, Archives of The Museum of Modern Art. When, after the acquisition of Vincent’s work, MoMA director Alfred H. Barr Jr. inquired in March 1945 about the work of other Haitian painters for the Museum’s collection, Peters sent images of artworks that he described as of the “popular variety,” adding, “Later on when the ‘regular’ Haitian painters get a bit more direction (which they are doing with great rapidity), I shall send you photographs of their works.”7DeWitt Peters to Alfred H. Barr Jr., March 12, 1945. René d’Harnoncourt Papers, II.16, Archives of The Museum of Modern Art.

Given the narratives that privilege Peters’s role in the creation of Haitian art, it is worth noting that Vincent’s painting precedes the formation of the Centre d’Art. Art historians, especially Carlo Avierl Célius, Philippe Thoby-Marcelin, and Michel Philippe Lerebours, have turned to the Haitian Indigenist movement to combat the art historical hegemony of the “primitive” art movement, and the overly strong emphasis on Peters’s role.8Philippe Thoby-Marcelin, Panorama de l’art haïtien (Port-au-Prince: Impr. de l’État, 1956); Michel-Philippe Lerebours, Haïti et ses peintres: De 1804 à 1980: Souffrances & Espoirs d’un Peuple, 2 vols. (Port-au-Prince, Haïti: Imprimeur II, 1989); Carlo A. Célius, Langage Plastique et Énonciation Identitaire: L’invention de l’art haïtien (Québec: Presses de l’Université Laval, 2007); Gérald Alexis, Artistes Haïtiens (Paris: Cercle d’art, 2007). In line with these art historians, in this essay, we highlight the role of MoMA and d’Harnoncourt in supporting art practices outside of the Centre d’Art through a close analysis of documents in the MoMA Archives. While d’Harnoncourt believed that the Centre d’Art had professionalized Haitian artists, he understood, because of his background in ethnography, the importance of the Indigenist movement.9René d’Harnoncourt to John Marshall, February 13, 1948. René d’Harnoncourt Papers, II.16, Archives of The Museum of Modern Art. There are few surviving paintings of the Indigenist movement, making Vincent’s 1940 Cock Fight a rare example. Similarly, there is scarce documentation from this period, and little archival documentation about the arts administrator Jean Chenet (c.1918–1963) and his role in creating the Foyer des Arts Plastiques, an arts institution founded in 1950 to compete with the Centre.10The Organization of American States (OAS) has another: Pétion Savain’s (1906–1973) 1938 painting Market on the Mountain. Note: the painting title according to the Art Museum of the Americas varies from the one recorded in the catalogue of the exhibition. International Business Machines Corporation, Contemporary Art of 79 Countries (International Business Machines Corporation, 1939). This essay does not aim to downplay the role of the Centre d’Art, but rather to shed light on other narratives that shaped Haitian art before and after the Centre’s creation.

With Indigenism, Haitian artists were, like their peers across Latin America—from Mexican muralists including Diego Rivera (1886–1957) to Ecuadorian painters including Camilo Egas (1889–1962)—participating in an artistic project to define a cultural identity independent from U.S. colonial influence. Although Haiti won its independence in 1804, the U.S. occupation of Haiti from 1915 to 1934 was a shock that led artists to find nationalistic inspiration in Haitian popular folklore and culture.

11Michel-Philippe Lerebours, “The Indigenist Revolt: Haitian Art, 1927-1944,” _Callaloo _15, no. 3 (Summer 1992), 712. Art historian Wendy Asquith recently contextualized the movement as “a variant of the hemispheric wave of Indigenismo sweeping Latin America in that era.”12Wendy Asquith, “Beyond Immobilised Identities: Haitian Art and Internationalism in the Mid-Twentieth Century,” in Alex Farquharson and Leah Gordon, Kafou: Haiti, Art and Vodou (Nottingham: Nottingham Contemporary, 2012), 41. Cuban artists, most notably Carlos Enríquez (1900–1957), interacted with Haitian artists when they traveled to the Centre d’Art in 1945 for the MoMA exhibition Modern Cuban Painters, which presented examples of their modernist interpretations of everyday life and local customs.13A number of the Cuban artists traveled to Haiti, and Carlos Enríquez in particular stayed on as a teacher and influenced artists including Maurice Borno and Luce Turnier, who experimented with his swirling, magical realist style. See the illustration in Philippe Thoby-Marcelin, Studio No. 3: Le Bulletin du Centre d’art, no. 1 (1945): 9. Many U.S. artists, including William Edouard Scott (1884–1964), traveled to Haiti in the 1930s and exchanged ideas, artworks, and artistic methods with local artists.14U.S.-born impressionist painter William Edouard Scott (1884–1964), who traveled on a fellowship in 1930–31, influenced the visual form this movement would take in Haiti with his almost-documentary depictions of market women and rural “types” made en plein air. Such international connections contradict the idea maintained by Rodman that Haitian artists were isolated and engaged in eccentric and insular projects.15Selden Rodman, The Miracle of Haitian Art (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1974).

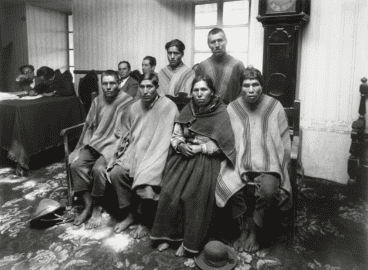

This painting by Vincent is exemplary of the Indigenist movement because of its ethnographic focus on rural and folk iconography, and also its documentary style. Born in 1911, Vincent was raised in Cap-Haïtien on the northern coast of Haiti.16Anonymous, “Biographic Note on René Vincent,” 1944–1945. René Vincent Object File, Department of Painting and Sculpture, The Museum of Modern Art. Vincent taught at the Lycée Philippe Guerrier of Cap-Haïtien. He worked as an art teacher at a local high school, practiced art along with local artists Jean-Baptiste Bottex (1918–1979) and Michelet Giordani (dates unknown), and in the late 1940s opened a branch of the Centre d’Art in his hometown.17Michel-Philippe Lerebours, “The Indigenist Revolt: Haitian Art, 1927–1944,” Callaloo 15, no. 3 (Summer 1992): 711–25. His work portrays scenes of quotidian life in Cap-Haïtien. Cock Fight represents a group of mostly men, engaged in one of Haiti’s most popular pastimes. Standing and gesticulating, the figures hover over a pair of fighting roosters. A woman in the distance to the left sells clairin, a multicolored sugarcane moonshine. Large, lush green trees, all too rare in today’s deforested Haiti, were even then signs of a romanticized depiction of the countryside. When this painting was shown in The Art of the United Nations exhibition at The Art Institute of Chicago in 1944–1945, the accompanying text on Haitian art called Vincent “a primitive who paints charming scenes of Haitian life,” in the context of “the gradual development of a truly individual and native school of painting.”18The Art Institute of Chicago, “Art of the United Nations,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 38, no. 6 (November 1944): 89–94. This critique is symptomatic of both a view of art from the Caribbean as underdeveloped and a refusal to understand it as in dialogue with international Indigenism—in which artists represented local cultures and traditions in paint in part in order to question their exclusion from high culture. Critics judged Haitian art as not on the level of that of more developed nations, finding it easier to accept it as a separate and unequal folk-art form.

Similarly, Chenet’s founding of the Foyer des Arts Plastiques as an alternative to the Centre d’Art, as evidenced in d’Harnoncourt’s support for Chenet’s training and projects, diverges from the usual narrative. On October 30, 1947, Chenet contacted d’Harnoncourt to introduce himself and request feedback on a grant proposal to study in the United States. As the secretary-archivist of the Centre d’Art, Chenet aimed to study the history of “primitive art, including its psychological and anthropological aspects,” as well as “do research in the technical organization of museums.”19Jean Chenet, Grant Application Attachment; Jean Chenet to René d’Harnoncourt, October 30, 1947. René d’Harnoncourt Papers, II.16, Archives of The Museum of Modern Art. Chenet hoped that his experience in the United States would lead to more effective museum practices and art historical research in Haiti, and moreover, result in a book examining Haitian art formally and contextually that “could be an important contribution to the field of modern art.”20Ibid. D’Harnoncourt wrote to the Rockefeller Foundation and Chenet was awarded a fellowship in 1948.21Svatava Roman Jakobson to Jean Chenet, January 12, 1948; René d’Harnoncourt to John Marshall, February 13, 1948; Jean Chenet to René d’Harnoncourt, April 9, 1948. René d’Harnoncourt Papers, II.16, Archives of The Museum of Modern Art. Chenet studied museum management at MoMA, the New School, and the Brooklyn Museum.22Philippe Thoby-Marcelin, Panorama de l’art haïtien, section III. In June 1949, he decided to go to Mexico for a little more than a month and, on his behalf, d’Harnoncourt wrote letters of introduction to Diego Rivera, Fernando Gamboa (1909–1990)—then director of the Museo de Bellas Artes—, among others.23René d’Harnoncourt to Fernando Gamboa, June 13, 1949; René d’Harnoncourt to Diego Rivera, June 13, 1949. René d’Harnoncourt Papers, II.16, Archives of The Museum of Modern Art. Chenet had been a muralist in Haiti, paid to produce works for the government according to his brother Jacques Chenet as recorded in “Chenet d’Haiti: The Story: An Interview with Jacques Chenet, Modern Silver Magazine (2012), http://www.modernsilver.com/chenet/jacqueschenetinterview.html

When Chenet returned to Haiti in September 1949, he encountered a tense environment at the Centre d’Art. The entire board had resigned and Peters recruited Chenet to help the organization recover and rebuild its administration. It was not the first time that Peters encountered friction with local artists and organizations. In October 1944, the Haitian-American Institute refused to support the Centre d’Art, because, according to Peters, “They wish us to be a branch of themselves and we do not see why we should be.”24Dewitt Peters to René d’Harnoncourt, October 27, 1944. René d’Harnoncourt Papers, II.16, Archives of The Museum of Modern Art. A few months later, Chenet left the Centre and became a curator at both the Musée du Peuple Haitien and the Palais des Beaux-Arts. Increasing disagreements between Peters and the artists, who sought greater freedom in terms of training and experimentation than the Centre’s emphasis on the “primitive” would allow, led to the creation in 1950 of the Foyer des Arts Plastiques by Chenet and artists previously associated with the Centre.25Artists are not named in Chenet’s letter to John Marshall, November 13, 1950. René d’Harnoncourt Papers, II.16, Archives of The Museum of Modern Art. Through the Foyer, Chenet organized an exhibition of these artists’ works, which was hosted by the Palais des Beaux-Arts. The Foyer not only included media traditionally associated with high art such as painting and sculpture, it also offered studio experience in jewelry, ceramics, woodworking, textiles, and basketry. The new institution embraced the work of artists from throughout Haiti and, unlike the Centre, it did not privilege painting or Vodou imagery, seeking instead to give artists wider berth to create freely without insisting on the “primitive” aesthetics or subjects that were appealing to foreigners.

MoMA was the first major institution abroad to acknowledge, through its acquisition of Vincent’s painting, the importance of the Indigenist painting movement in Haiti. Later, MoMA supported artistic production and development by encouraging a Haitian arts administrator who would support the formation of a new arts institution. Emerging from the MoMA Archives, the stories of Vincent and Chenet demonstrate that an exclusive focus on the Centre d’Art limits our understanding of Haitian art and fails to encompass MoMA’s exchange with Haitian art in the 1940s. By understanding artistic production and institutions from within Haiti, rather than from outside it, one can formulate a narrative that underscores the Haitian Indigenist movement’s position in the art historical narrative and the importance that Haitian artists and arts administrators assigned to it.

- 1René d’Harnoncourt to John Marshall, February 13, 1948. René d’Harnoncourt Papers, II.16, Archives of The Museum of Modern Art.

- 2René d’Harnoncourt to Edmond Mangonès, December 15, 1943. René d’Harnoncourt Papers, II.16, Archives of The Museum of Modern Art. The Bureau was formed in 1941 and organized exhibitions.

- 3After d’Harnoncourt inquired about the painting in a letter dated November 25, 1943, Peters followed up twice regarding d’Harnoncourt’s potential purchase of it—once in December 1943 and again in March 1944. The two then negotiated the price and agreed on $30 plus shipping expenses. DeWitt Peters to René d’Harnoncourt, December 30, 1944; DeWitt Peters to René d’Harnoncourt, March 29, 1944; René d’Harnoncourt to DeWitt Peters, April 9, 1944; DeWitt Peters to René d’Harnoncourt, May 17, 1944; René d’Harnoncourt to DeWitt Peters, May 31, 1944. René d’Harnoncourt Papers, II.16, Archives of The Museum of Modern Art.

- 4Breton promoted the painter Hector Hyppolite in particular, and dedicated a short chapter to him in his book. André Breton, Le surréalisme et la peinture (Paris: Gallimard, 1965), 308-312.

- 5Gérald Alexis, “Il Y a Quarante Ans, S’ouvrait Pour L’épanouissement de l’art Haïtien,” Le Nouvelliste, May 3, 1984.

- 6DeWitt Peters to Monroe Wheeler, January 17, 1945; DeWitt Peters to Luis de Zulueta Jr., February 13, 1945. René d’Harnoncourt Papers, II.16, Archives of The Museum of Modern Art.

- 7DeWitt Peters to Alfred H. Barr Jr., March 12, 1945. René d’Harnoncourt Papers, II.16, Archives of The Museum of Modern Art.

- 8Philippe Thoby-Marcelin, Panorama de l’art haïtien (Port-au-Prince: Impr. de l’État, 1956); Michel-Philippe Lerebours, Haïti et ses peintres: De 1804 à 1980: Souffrances & Espoirs d’un Peuple, 2 vols. (Port-au-Prince, Haïti: Imprimeur II, 1989); Carlo A. Célius, Langage Plastique et Énonciation Identitaire: L’invention de l’art haïtien (Québec: Presses de l’Université Laval, 2007); Gérald Alexis, Artistes Haïtiens (Paris: Cercle d’art, 2007).

- 9René d’Harnoncourt to John Marshall, February 13, 1948. René d’Harnoncourt Papers, II.16, Archives of The Museum of Modern Art.

- 10The Organization of American States (OAS) has another: Pétion Savain’s (1906–1973) 1938 painting Market on the Mountain. Note: the painting title according to the Art Museum of the Americas varies from the one recorded in the catalogue of the exhibition. International Business Machines Corporation, Contemporary Art of 79 Countries (International Business Machines Corporation, 1939).

- 11Michel-Philippe Lerebours, “The Indigenist Revolt: Haitian Art, 1927-1944,” _Callaloo _15, no. 3 (Summer 1992), 712.

- 12Wendy Asquith, “Beyond Immobilised Identities: Haitian Art and Internationalism in the Mid-Twentieth Century,” in Alex Farquharson and Leah Gordon, Kafou: Haiti, Art and Vodou (Nottingham: Nottingham Contemporary, 2012), 41.

- 13A number of the Cuban artists traveled to Haiti, and Carlos Enríquez in particular stayed on as a teacher and influenced artists including Maurice Borno and Luce Turnier, who experimented with his swirling, magical realist style. See the illustration in Philippe Thoby-Marcelin, Studio No. 3: Le Bulletin du Centre d’art, no. 1 (1945): 9.

- 14U.S.-born impressionist painter William Edouard Scott (1884–1964), who traveled on a fellowship in 1930–31, influenced the visual form this movement would take in Haiti with his almost-documentary depictions of market women and rural “types” made en plein air.

- 15Selden Rodman, The Miracle of Haitian Art (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1974).

- 16Anonymous, “Biographic Note on René Vincent,” 1944–1945. René Vincent Object File, Department of Painting and Sculpture, The Museum of Modern Art. Vincent taught at the Lycée Philippe Guerrier of Cap-Haïtien.

- 17Michel-Philippe Lerebours, “The Indigenist Revolt: Haitian Art, 1927–1944,” Callaloo 15, no. 3 (Summer 1992): 711–25.

- 18The Art Institute of Chicago, “Art of the United Nations,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 38, no. 6 (November 1944): 89–94.

- 19Jean Chenet, Grant Application Attachment; Jean Chenet to René d’Harnoncourt, October 30, 1947. René d’Harnoncourt Papers, II.16, Archives of The Museum of Modern Art.

- 20Ibid.

- 21Svatava Roman Jakobson to Jean Chenet, January 12, 1948; René d’Harnoncourt to John Marshall, February 13, 1948; Jean Chenet to René d’Harnoncourt, April 9, 1948. René d’Harnoncourt Papers, II.16, Archives of The Museum of Modern Art.

- 22Philippe Thoby-Marcelin, Panorama de l’art haïtien, section III.

- 23René d’Harnoncourt to Fernando Gamboa, June 13, 1949; René d’Harnoncourt to Diego Rivera, June 13, 1949. René d’Harnoncourt Papers, II.16, Archives of The Museum of Modern Art. Chenet had been a muralist in Haiti, paid to produce works for the government according to his brother Jacques Chenet as recorded in “Chenet d’Haiti: The Story: An Interview with Jacques Chenet, Modern Silver Magazine (2012), http://www.modernsilver.com/chenet/jacqueschenetinterview.html

- 24Dewitt Peters to René d’Harnoncourt, October 27, 1944. René d’Harnoncourt Papers, II.16, Archives of The Museum of Modern Art.

- 25Artists are not named in Chenet’s letter to John Marshall, November 13, 1950. René d’Harnoncourt Papers, II.16, Archives of The Museum of Modern Art.