The Rauschenberg Overseas Cultural Initiative (ROCI) was a large-scale international traveling exhibition organized by American artist Robert Rauschenberg that doubled as a cultural exchange program. Between 1984 and 1990, Rauschenberg and his team held the ROCI exhibition in ten countries—Mexico, Chile, Venezuela, China, Tibet, Japan, Cuba, the Soviet Union, East Germany, and Malaysia—before the project concluded in 1991. This is the second and final section of an essay by Hiroko Ikegami on the topic, excerpted from the exhibition catalog Robert Rauschenberg: Among Friends.

ROCI WELCOMED, ROCI CONFRONTED

In the Soviet Union of perestroika, ROCI matched the government’s shifting political needs even more than in China. Unlike China, the Soviet Union was not entirely disconnected from Western culture after World War II. Amerika, a lavishly illustrated magazine published by the United States Information Agency, had featured a number of articles on Rauschenberg and Pop art in the 1960s and ’70s, including color reproductions of works such as Bed (1955) and Monogram (1955– 59).1Kachurin, “The ROCI Road to Peace,” p. 31. As the art historian Pamela Kachurin points out, in a country where abstraction was deemed “decadent,” the representational, everyday images of Pop art, including Rauschenberg’s work, could be interpreted as modern yet potentially antibourgeois at the same time. Indeed, one Soviet critic, writing in 1985, described Pop as an “original protest, an anarchist rebellion, not only against abstraction, but against bourgeois society.”2Tatyana Yureva, “Protiv burzhuznoi propagandy v sfere iskusstva,” Iskusstvo no. 2 (February 1970), pp. 44–48.Quoted here from Kachurin, “The ROCI Road to Peace,” p. 31.

Rauschenberg’s art thus offered a readymade compromise to the Soviet ministry of culture and to the Artists’ Union of the USSR (an organization of artists and critics who embraced socialist realism as the official Soviet art), both needing to demonstrate a reformist policy while appeasing the conservatives who wanted to maintain the status quo in the Soviet art scene. It served the Russian people’s growing hunger for Western culture as well: the exhibition sold 145,000 tickets, in addition to free tickets given to members of the Communist Party. Saff remembers long lines at the Tretyakov Gallery, with “Soviets coming from every republic to Moscow, taking weeks to travel and, for all I know, spending their last ruble to see the show.”3Rauschenberg and Saff, “A Conversation about Art and ROCI,” p. 158. In Moscow ROCI USSR was accompanied by another Soviet-organized exhibition at the First Gallery, Rauschenberg to Us, We to Rauschenberg, structured as a bilateral art exchange featuring works by about thirty nonunion Russian artists who created works in tribute to the American artist. The parallel exhibitions evolved into the Soviet Union’s presentation at the 1990 Venice Biennale, making Rauschenberg the first (and most likely the last) American artist featured in the Russian Pavilion.4Ibid., p. 174. It therefore hardly seemed rhetorical exaggeration when the poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko, who wrote an essay in the ROCI USSR catalogue, declared at the opening, “I believe no more Iron Curtain will divide U.S. and Russian artists.”5Yevgeny Yevtushenko, quoted in Kotz, “The ROCI Road Show,” p. 48.

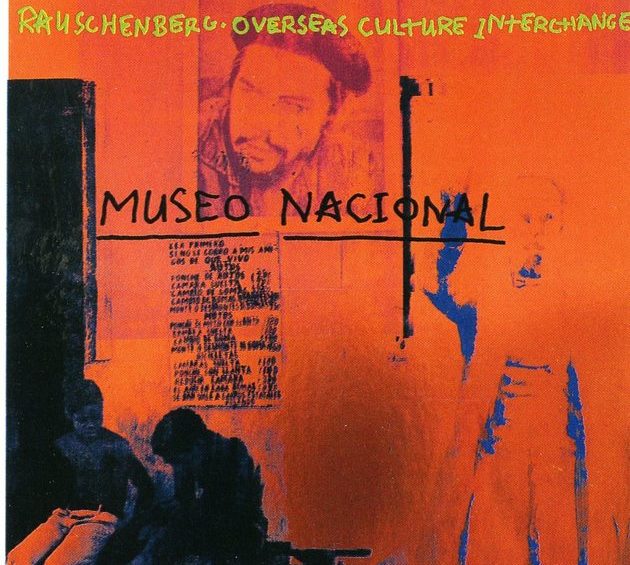

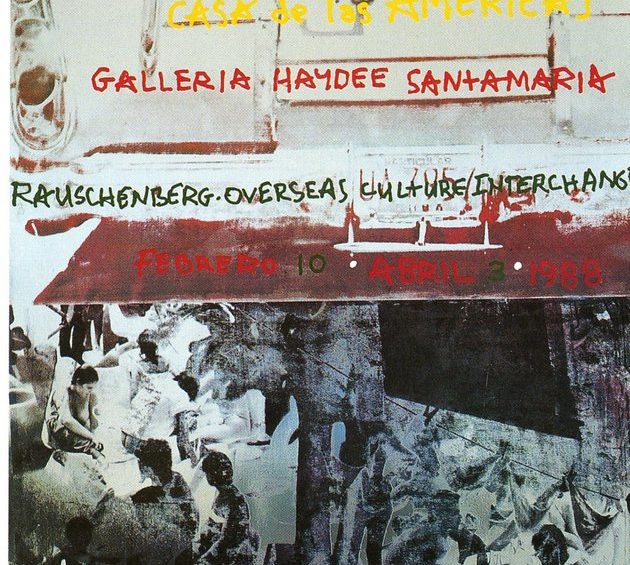

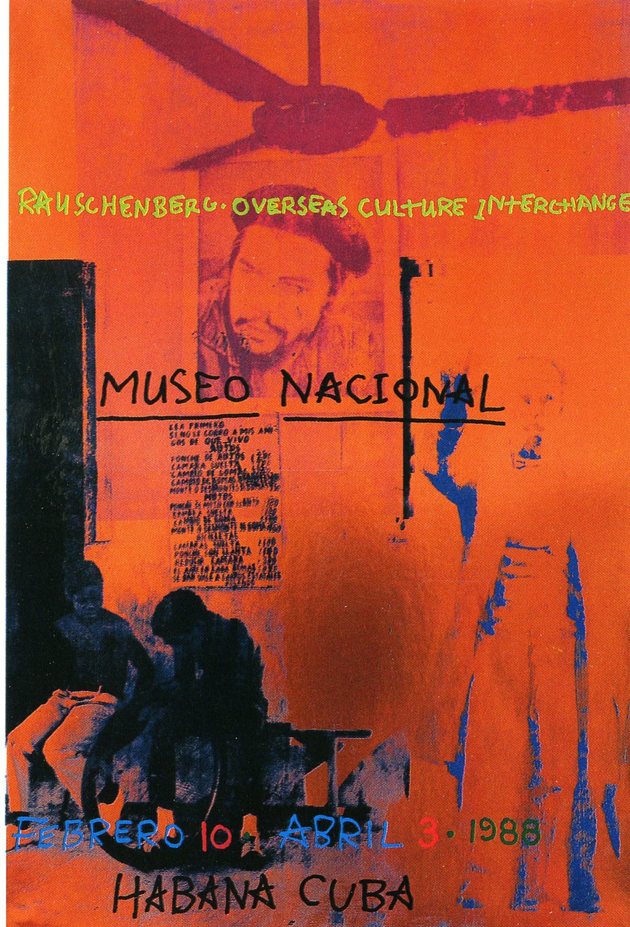

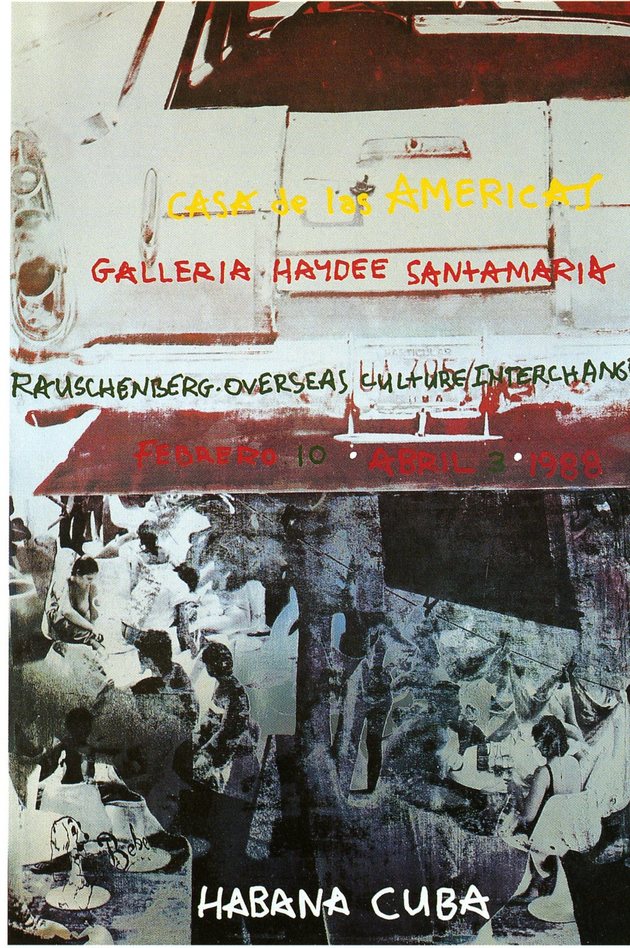

Yet ROCI caused controversy as well as enthusiasm. In China, for instance, when young, underground artists found out that Rauschenberg had agreed to make a portrait of Deng Xiaoping for the cover of Time magazine’s “Man of the Year” issue of 1985, he was criticized for cooperating with the government.6See Ikegami, “ROCI East: Rauschenberg’s Encounters in China,” pp. 184–86. A similar confrontation, although a more strategic one, occurred in Cuba in 1988.7The negotiation for ROCI Cuba began when Saff’s brother, a mathematician, was invited to lecture at the University of Havana and delivered a letter from Saff to the Cuban minister of culture. See Rauschenberg and Saff, “A Conversation about Art and ROCI,” p. 171. There ROCI received especially generous treatment, arranged by an eminent poet, Roberto Fernández Retamar, who was the president of Casa de las Américas, an institution established in 1959 after the Cuban revolution to develop cultural relationships among the Latin American and Caribbean countries. Cuba covered all the exhibition’s expenses,8Saff wrote to Rauschenberg from Cuba, “They have agreed to pay all expenses with the exception of your air fare to and from Cuba.” Saff, letter to Rauschenberg, August 12, 1987. Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Archives. offered three exhibition spaces (Casa de las Américas, the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, and the Castillo de la Fuerza, a sixteenth- century fortress that had never been used as a gallery before), and even sent a vessel called Bay of Pigs to Japan to pick up Rauschenberg’s works there. Fidel Castro hosted Rauschenberg at an official dinner in the Museo de la Revolución (the former presidential palace in Havana), where he invited the American artist to vacation in his summer place, Varadero. A different poster was created for each of the exhibition venues, all of which flew green ROCI banners with turtle logos fluttering in the wind.9See Helen L. Kohen, “To Cuba, with Art,” Miami Herald, February 21, 1988, p. 2K.

While Cubans hungry for information from the United States flocked to the show, some young artists questioned Rauschenberg’s “invasion.” When he began a lecture at the Museo Nacional, one of the opening events, three men stormed into the hall, two of them—Carlos Rodríguez Cárdenas and Francisco Lastra—bearing a large panel depicting a profile of an “Indian” with the line “Very Good Rauschenberg.” Despite the moderator’s request that he wait until the end of the lecture, the third man, Glexis Novoa, insisted in Spanish—which Rauschenberg did not understand—that the American artist autograph one of the ROCI Cuba posters. Novoa made a point of having him use a brush and paint, thinking that it would later enhance the poster’s value. Rauschenberg, drunk but not offended, autographed it as requested.10Glexis Novoa, Skype interview with the author, March 4, 2016. The young men, members of the anarchist Grupo Provisional,11Grupo Provisional was formed in 1986 with Novoa and Carlos Rodríguez Cárdenas as its core members. As the word “provisional” may suggest, this anarchist artistic and political group had no fixed membership, recruiting participants for each performance. On the Grupo Provisional see Luis Camnitzer, New Art of Cuba, 1994 (rev. ed. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2003), pp. 178–81. planned this performance to critique the government’s decision to allow an American celebrity artist to monopolize their cultural space.

At the same event, as a separate performance, the artist Aldo Menéndez personified “El Indio.” Sitting on the floor directly in front of Rauschenberg, wearing only a loincloth around his waist, body paint to connote the indigenous people of the Americas, and with two arrows before him, he bowed to Rauschenberg a few times during the lecture while otherwise listening inscrutably. As the art historian Rachel Weiss has pointed out, these performances were intended to expose what these young Cubans considered the self-colonizing attitudes of their national cultural institutions.12Rachel Weiss, “Performing Revolution: Arte Calle, Grupo Provisional, and the Response to the Cuban National Crisis, 1986–1989,” in Blake Stimson and Gregory Sholette, eds., Collectivism after Modernism: The Art of Social Imagination after 1945 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), pp. 127–28. They were staging themselves as the “conquered”—young groupies infatuated with a prestigious American artist in the case of Grupo Provisional, the mysterious yet subservient “Indian” in the case of Menéndez. All in their way played on the myth of the generosity and naïveté of the indigenous people of the Antilles, legendarily said to have given their conquerors gold in exchange for mirrors.13In an anthology of Cuban legends published in 1909, Frances Jackson Stoddard writes, “Many things were brought and given as presents to the Indians, glittering things that seemed wonderful, especially the small mirrors in which they could see the marvel of reflection of their own countenances.” Stoddard, “Indian Legends of the Conquest Period,” in As Old as the Moon. Cuban Legends: Folklore of the Antillas (New York: Doubleday, Page, 1909), p. 107. The gesture had its ironies: Rauschenberg himself was part Cherokee in descent, although the Cuban artists didn’t know it at the time.

Though Novoa’s protest was aimed at the American “art imperialist,” his target was not Rauschenberg himself but the Cuban government. Novoa actually liked the artist—“You cannot avoid liking Rauschenberg as an artist,” he would later say— and Cuban artists were talking about the ROCI exhibition long after it closed, speaking of before-and-after-Rauschenberg eras just as Chinese artists did.14Novoa, Skype interview with the author. Since the Bienal de la Habana had been inaugurated four years earlier, Novoa and his fellows had some familiarity with contemporary art. But that exhibition had so far focused on “non-Western art,” inviting artists from Latin America and the Caribbean only in 1984 and including artists from Africa, Asia, and the Middle East in 1986. ROCI was the first big show of a North American contemporary artist in Cuba. And besides the work itself, it also implicitly offered lessons in exhibition- making: how to make different uses of materials and objects, how to fill gigantic spaces in multiple venues, how to renovate galleries into a condition suitable for the installation of art. Since white paint was unavailable in Cuba, Rauschenberg even brought it with him to paint the walls.15“The Reminiscences of Donald Saff,” p. 115. For Novoa, in short, the most impressive aspect of ROCI was the way Rauschenberg and his team “transformed the museum in an American way.”16Novoa, Skype interview with the author.

INDUCING DIVERSITY IN THE GLOBAL ART SCENES

This “American” factor is crucial in evaluating ROCI’s legacy. Jack Cowart, a curator at the National Gallery when the show finally came to Washington, observed that “to foreign audiences, especially those in countries where freedom of information is unknown, the exhibition makes a powerful statement about America itself.”17Jack Cowart, quoted in Kotz, “The ROCI Road Show,” p. 50. With the end of the Cold War and of the cultural blockade between the East and West, ROCI positioned Rauschenberg, long seen as a quintessentially “American” artist, as a model of what an artist could do in a “free” society.

Indeed, the Moscow painter and critic Leonid Bazhanov declared, “To us, the show symbolizes freedom.”18Leonid Bazhanov, quoted in ibid., p. 48. Another Soviet critic saw Rauschenberg’s work as a proof of how contemporary art can grow “when it is free,” asking “How did we live without Rauschenberg?”19Elena Chernevich, quoted in Kachurin, “The ROCI Road to Peace,” p. 38. It was this newly acquired “freedom,” even in its limited form, that allowed the five artists chosen from Rauschenberg to Us, We to Rauschenberg to debut at the 1990 Venice Biennale. ROCI also catalyzed the emergence of a commercial art system in Russia: the First Gallery, which presented Rauschenberg to Us, We to Rauschenberg, was the first commercial gallery to appear in the country since the revolution of 1917. Bazhanov, once an unofficial artist, said, “If only this had happened twenty years ago, it would have helped me greatly. For [younger] artists, though, the exhibition shows what they can do.”20Bazhanov, quoted in Kotz, “The ROCI Road Show,” p. 50. ROCI thus helped to bridge the cultural time lag between divided countries.

Yet it would be misleading to think of ROCI as an endeavor to “Americanize” the art world. Its more profound legacy may have been to provide a destination: it prompted many young artists to move. Both Novoa and Rodríguez Cárdenas started working in the United States after encountering Rauschenberg.21Novoa now divides his time between Miami and Havana. Rodríguez Cárdenas has lived in New Jersey since the early 1990s, Francisco Lastra in Mexico since the early 1990s. Novoa notes that for many Cuban artists, Mexico was a more realistic destination than the United States in terms of acquiring visas and affordable flight fares. Novoa, e-mail message to the author, July 17, 2016. Xu Bing and many other underground Chinese artists similarly moved to either the United States or Europe, including some who had taken issue with Rauschenberg’s project. Of course each one was an individual case for whom many different motives may have prevailed, and their moves might have happened anyway, with or without Rauschenberg. Nonetheless, they formed a vital part of a larger, irreversible change in the global art scene of the late 1980s, when the contemporary-art system was beginning to globalize in full force; and ROCI encouraged this mobility, at a moment that saw a profusion of art fairs and biennials outside the traditional centers, and of artists from the former Eastern Bloc and the so-called Third World stepping one after another onto these international stages.

What mattered was not mobility itself but its effect: the globalization and diversification of the world’s art scenes. While change would have come sooner or later, young and aspiring artists in many of the countries that hosted ROCI responded deeply to seeing what contemporary art was like with their own eyes. So did the general public, hungry to reconnect with the world beyond their local regimes. Rauschenberg’s work on ROCI, if somewhat contradictory in nature, torn between altruistic service and egocentric self-aggrandizement, was nonetheless a crucial catalyst for the diversification of the global art scene in the years to come.

This is the second and final section of an essay by Hiroko Ikegami on the American artist Robert Rauschenberg, excerpted from the exhibition catalog Robert Rauschenberg: Among Friends. Read the first section here.

- 1Kachurin, “The ROCI Road to Peace,” p. 31.

- 2Tatyana Yureva, “Protiv burzhuznoi propagandy v sfere iskusstva,” Iskusstvo no. 2 (February 1970), pp. 44–48.Quoted here from Kachurin, “The ROCI Road to Peace,” p. 31.

- 3Rauschenberg and Saff, “A Conversation about Art and ROCI,” p. 158.

- 4Ibid., p. 174.

- 5Yevgeny Yevtushenko, quoted in Kotz, “The ROCI Road Show,” p. 48.

- 6See Ikegami, “ROCI East: Rauschenberg’s Encounters in China,” pp. 184–86.

- 7The negotiation for ROCI Cuba began when Saff’s brother, a mathematician, was invited to lecture at the University of Havana and delivered a letter from Saff to the Cuban minister of culture. See Rauschenberg and Saff, “A Conversation about Art and ROCI,” p. 171.

- 8Saff wrote to Rauschenberg from Cuba, “They have agreed to pay all expenses with the exception of your air fare to and from Cuba.” Saff, letter to Rauschenberg, August 12, 1987. Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Archives.

- 9See Helen L. Kohen, “To Cuba, with Art,” Miami Herald, February 21, 1988, p. 2K.

- 10Glexis Novoa, Skype interview with the author, March 4, 2016.

- 11Grupo Provisional was formed in 1986 with Novoa and Carlos Rodríguez Cárdenas as its core members. As the word “provisional” may suggest, this anarchist artistic and political group had no fixed membership, recruiting participants for each performance. On the Grupo Provisional see Luis Camnitzer, New Art of Cuba, 1994 (rev. ed. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2003), pp. 178–81.

- 12Rachel Weiss, “Performing Revolution: Arte Calle, Grupo Provisional, and the Response to the Cuban National Crisis, 1986–1989,” in Blake Stimson and Gregory Sholette, eds., Collectivism after Modernism: The Art of Social Imagination after 1945 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), pp. 127–28.

- 13In an anthology of Cuban legends published in 1909, Frances Jackson Stoddard writes, “Many things were brought and given as presents to the Indians, glittering things that seemed wonderful, especially the small mirrors in which they could see the marvel of reflection of their own countenances.” Stoddard, “Indian Legends of the Conquest Period,” in As Old as the Moon. Cuban Legends: Folklore of the Antillas (New York: Doubleday, Page, 1909), p. 107.

- 14Novoa, Skype interview with the author.

- 15“The Reminiscences of Donald Saff,” p. 115.

- 16Novoa, Skype interview with the author.

- 17Jack Cowart, quoted in Kotz, “The ROCI Road Show,” p. 50.

- 18Leonid Bazhanov, quoted in ibid., p. 48.

- 19Elena Chernevich, quoted in Kachurin, “The ROCI Road to Peace,” p. 38.

- 20Bazhanov, quoted in Kotz, “The ROCI Road Show,” p. 50.

- 21Novoa now divides his time between Miami and Havana. Rodríguez Cárdenas has lived in New Jersey since the early 1990s, Francisco Lastra in Mexico since the early 1990s. Novoa notes that for many Cuban artists, Mexico was a more realistic destination than the United States in terms of acquiring visas and affordable flight fares. Novoa, e-mail message to the author, July 17, 2016.