In this essay, Tamar Margalit, Curatorial Assistant in Painting & Sculpture at MoMA, considers two works by the Polish artist Magdalena Abakanowicz in the museum’s collection. Yellow Abakan and Pregnant engage with a diverse range of materials that address the limitations of working as a female sculptor under state socialism. Most recently, Yellow Abakan was included in the Making Space: Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction exhibition in 2017 at MoMA, which opened in the same month as Abakanowicz’s passing, at the age of 86.

The Polish artist Magdalena Abakanowicz (1930–2017), who passed away in April, forged a reputation as a remarkably active presence on the international stage in the postwar period. As a woman artist working behind the Iron Curtain, her success is all the more remarkable. Two key sculptures by Abakanowicz in MoMA’s collection, Yellow Abakan (1967–68) and Pregnant (1981–82), reveal the ingenuity of her approach and her refusal to cede to conventions or artistic trends. Both works were on view in the galleries as part of a focused presentation on the occasion of the artist’s eighty-fifth birthday (in 2015). More recently, Yellow Abakan was included in Making Space: Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction (2017).

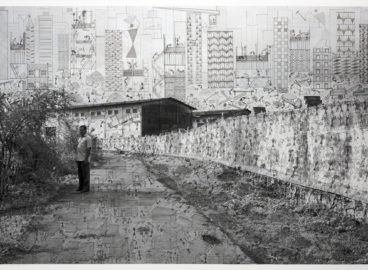

Abakanowicz attended the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw in 1950–54, a time in which Socialist Realism was strictly enforced as the only sanctioned style in Poland. Stalin’s death, in 1953, brought about a certain easing of restrictions (albeit only temporarily), allowing Abakanowicz to benefit from a burst of intellectual and creative activity that was felt around the country. She began to move in the artistic circles that coalesced around the Constructivist artists of the preceding generation, including Wladyslaw Strzemiński, Katarzyna Kobro, and Henryk Stażewski. Although she worked predominantly in painting at that time, Abakanowicz drew inspiration from the bustling Polish avant-garde theater scene, and especially the irreverence and iconoclastic impulses of the theater personas Tadeusz Kantor and Jerzy Grotowski. Yet by the late 1950s, as state censorship regained its grip, she began searching outside of the dominant artistic mediums for a creative outlet that would be less regulated. At the urging of the fiber artist Maria Laszkiewicz, who also offered Abakanowicz a modest studio space in her workshop, she turned to weaving, a craft she had studied at the Academy of Fine Arts as part of her vocational training and which she now developed as an art form that would come to define her practice in the two decades to come.

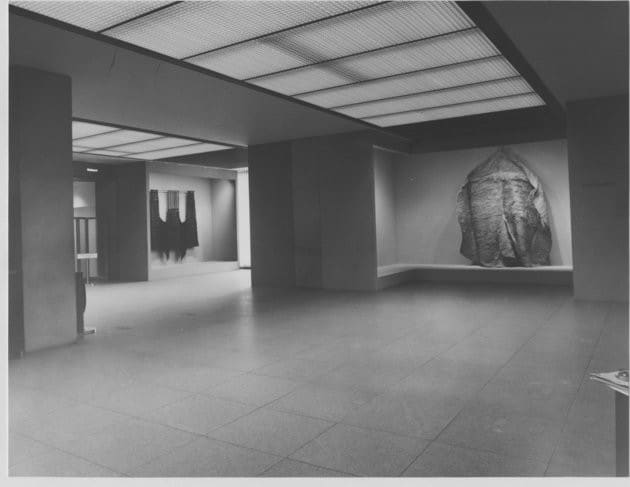

Abakanowicz’s most iconic works from this early period are woven constructions made of sisal—a coarse plant fiber that she derived from discarded ropes. These comprise numerous surface layers, folds, and appendages. While the works are able to be stored and to travel flat—crucial given the artist’s confined working conditions—they become monumental three-dimensional objects once suspended from the ceiling. With their organic materiality and undulating shapes, these works, known as the “Abakans” (shorthand for the artist’s name), carry distinct bodily associations—evoking vaginal imagery, animal skins, or tribal garments. At the time of their creation, the Abakans straddled what were then considered discrete categories of the arts: the decorative arts on the one hand, with which weaving was often associated, and fine art on the other. Yet, as the artist later reminisced, they didn’t fit neatly with the trends of either category. “The Abakans irritated people,” Abakanowicz said. “They came at the wrong time. In fabric it was the French tapestry, in art: Pop art and Conceptual art; and here was a huge, magical thing.”1Roman Dziadkiewicz and Dominik Kurylek, Magdalena Abaknowicz (Krakow: The National Museum in Krakow, 2010), 18. Under the Soviet regime, art had to serve a function in society, and any trappings of spirituality were deemed suspect. The Abakans’ close association with mysticism was therefore politically charged, and was acknowledged by the artist only in hindsight.

Yellow Abakan was exhibited in MoMA’s 1969 exhibition Wall Hangings and acquired by the Museum five years later. That exhibition, organized under the auspices of the Museum’s Department of Architecture and Design, was responsible for introducing the burgeoning developments in fiber art, and for broadly staking a place for them within the “context of twentieth-century art.”

2The Museum of Modern Art, press release no. 25, February 25, 1969, https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_press-release_326605.pdf, accessed September 14, 2017. It is telling that Yellow Abakan made its way into MoMA’s collection as a design object and not as sculpture. As has been noted, the general shortage of paintings and sculptures by women artists in MoMA’s collection around the time of the Wall Hangings exhibition—and, even more so, by non-Western artists—is somewhat allayed when we look at the broader holdings of the Museum around that time, in “mediums whose histories occupied the margins of the art world, and where women therefore found easy access.”3Cornelia Butler, “The Feminist Present: Women Artists at MoMA,” in Modern Women: Women Artists at The Museum of Modern Art, eds. Cornelia Butler and Alexandra Schwartz (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2010), 25.

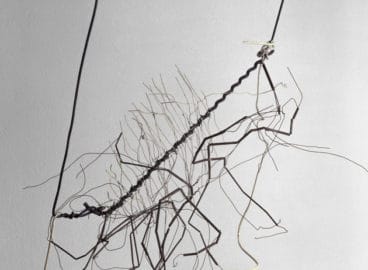

Although the Abakans helped cement Abakanowicz’s reputation, by the late 1970s, she began to feel constricted by them, as well as by the Polish artistic milieu with which she had become associated (and wryly referred to as “the ghetto of weavers”4Michael Bronson, “Survivor Art,” New York Times Magazine, November 29, 1992, 50.). She began to turn toward a more fully fledged sculptural practice that broadened her interest in organic materials and forms. Abakanowicz’s works from this period on were mostly conceived as “cycles,” a term that not only captures their treatment of a single theme across a group of elements but also relates metaphorically to her occupation with biological cycles and their attendant themes of metamorphosis, decay, and renewal. Pregnant, a signature work from this period, comprises twenty-three elements, which range in size from large, pod-shaped parcels packed with twigs—whose bulges are suggestive of the work’s title—to individual branches. Each sculptural element is intricately coiled in wire, as if encased in a delicate metal armature, and placed directly on the floor in loose configuration. If Yellow Abakan registers as a shell or a skin, in Pregnant we may see an “invitation to look inside the body cavity itself,”5Barbara Rose, Magdalena Abakanowicz (New York: Marlborough Gallery, 1994), 94. to the internal matter of bones and sinew. Together, these works speak to Abakanowicz’s singular ability to mold castaway objects into highly charged, almost physical beings that pulsate with life.

- 1Roman Dziadkiewicz and Dominik Kurylek, Magdalena Abaknowicz (Krakow: The National Museum in Krakow, 2010), 18.

- 2The Museum of Modern Art, press release no. 25, February 25, 1969, https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_press-release_326605.pdf, accessed September 14, 2017.

- 3Cornelia Butler, “The Feminist Present: Women Artists at MoMA,” in Modern Women: Women Artists at The Museum of Modern Art, eds. Cornelia Butler and Alexandra Schwartz (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2010), 25.

- 4Michael Bronson, “Survivor Art,” New York Times Magazine, November 29, 1992, 50.

- 5Barbara Rose, Magdalena Abakanowicz (New York: Marlborough Gallery, 1994), 94.