At the age of sixty-seven, Polish artist Zofia Rydet began her photographic series Sociological Record in an effort to document Polish individuals in their private and deeply personal spaces. Because the artist had to frequently travel to photograph all her subjects, which prevented her from taking the time to print her work, only a small portion of the series was known until the 2015 exhibition Zofia Rydet. Record, 1978-1990 at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw. Sebastian Cichocki, chief curator of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, surveys and highlights a handful the 20,000 black-and-white photographs taken by Rydet that portray the sick, artists’ homes, professions, and other unseen societal subjects.

Sociological Record by Zofia Rydet (born 1911 in the Polish city of Stanisławów, now Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine; died 1997 in Gliwice, Poland) is a sweeping photographic project from the twentieth century that only in recent years has come to be examined within the field of contemporary art.1Portions of Sociological Record have been presented at such shows as the XII Baltic Triennial at the Contemporary Art Centre in Vilnius, Lithuania (2015) and The Keeper at the New Museum in New York (2016). Even though fragments of the series were presented at a number of exhibitions during the photographer’s lifetime, and dozens of articles in the specialist and popular press have been devoted to the series, there are still many unknowns that art historians, curators, and researchers from other fields (mainly ethnographers) must grapple with in their quest for knowledge about the material culture in Poland in the 1970s and 1980s. In 1979, five photographs from Sociological Record joined the MoMA collection. Rydet donated these images, which she selected as representative of the series (shots of the elderly, married couples, and single people in rural interiors) during her visit to the United States in 1979 for the exhibition Fotografia Polska, 1839–1979 at the International Center of Photography in New York.

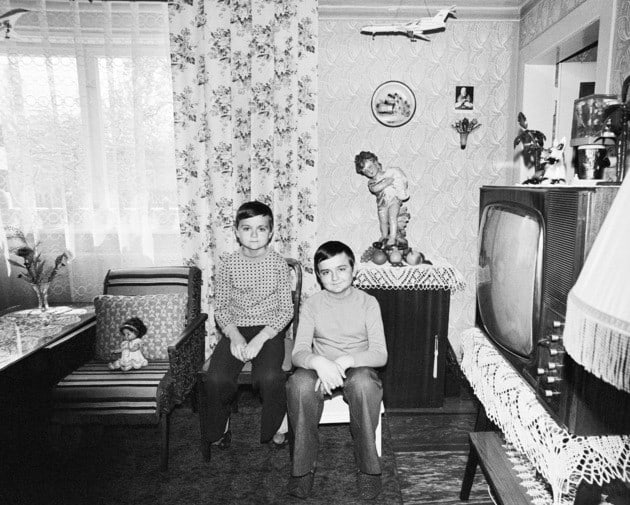

Rydet began work on Sociological Record relatively late in her career, at age sixty-seven, as an artist holding a distinct and singular position in the community of Polish photographers dominated at the time by men and having extensive contacts with neo-avant-garde circles.2Rydet was known then primarily for two photo series published in book form: Mały człowiek (Little Person) (1965), devoted to children and adolescence, and Świat uczuć i wyobraźni (World of Emotions and Imagination) (1979), a set of collages dominated by surreal motifs—mannequins, gloves, dolls, and so on. Rydet was also interested in subjects such as state infrastructure for children and the elderly (such as orphanages, schools, social welfare homes, etc.) The series comprises nearly twenty thousand photos taken in more than a hundred Polish villages and towns. The concept for the series, which evolved into a photographic program realized over nearly three decades, was simple: to archive the interiors of homes together with their inhabitants. Rydet shot with a wide-angle lens, typically with a strong flash, picking out the details of the interior, while each of her hosts posed in front of a wall and stared straight into the lens. She was intrigued by how their individual aesthetic preferences, political views, and religious beliefs were manifest through the arrangement of their private spaces. She was convinced that objects collected in private spaces define people and “reveal their psyche.” The idea for the title Sociological Record probably came from the art historian Urszula Czartoryska,3Urszula Czartoryska (1934–1998), art historian and curator, affiliated for decades with the Museum of Art in Łódź as director of the Department of Photography and Visual Techniques. and was seized upon by Rydet despite her own reservations as to the “scientific” nature of the method in which she had chosen to work. The prevailing tendency, echoing interpretations of Polish twentieth-century literature, was to interpret Rydet’s work in the spirit of humanistic photography and the sentimental archiving of an image of the “premodern” countryside inescapably subjected to modernizing forces. The series landed at a specific moment in the theoretical reflection on Polish photography, just when “the possibility of sociological photography” was being debated (culminating in the first nationwide review of sociological photography in Bielsko-Biała in 1980). In the late 1970s the folk publishing cooperative Ludowa Spółdzielnia Wydawnicza considered publishing Sociological Record in the form of a photo album, but this idea was abandoned, probably due to the fear of disseminating the potentially unflattering image of Poland as backward and destitute, which may be suggested by the series. A more careful analysis of the artist’s ambitions and the context of her initiative places Sociological Record close to other social photographic programs, such as Chauncey Hare’s Protest Photographs from the 1960s and 1970s, in which the political nature of the photography is founded on discipline, the anti-spectacular nature of the image, and the application of “cold” conceptual “working rules.”

Sociological Record was never completed. In fact, Rydet even began to circle back to the homes she had visited earlier to document the changes they had undergone. Constantly occupied with traveling and taking pictures, but also weakened by age and failing eyesight, the artist did not make prints from most of her negatives. Consequently, until recently, only a small portion of the work was known—with some of the same shots shown over and over, in various formats and exhibitions. In 2015 the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw held an exhibition attempting to reconstruct a never-realized exhibition based on the guidelines set forth in Rydet’s notes and private correspondence, in which she left a fairly precise scenario for presentation of Sociological Record.4The exhibition Zofia Rydet. Record, 1978–1990(September 2015–January 2016; curators Sebastian Cichocki and Karol Hordziej) was part of a larger research and popularization project concerning Rydet’s archive carried out by four institutions: the Foundation for Visual Arts in Poland, the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, the Zofia Rydet Foundation, and the Gliwice Museum. The fruits of these efforts include digitization and public access to nearly the entire Sociological Record and numerous source materials at the online archive www.zofiarydet.com. Following the artist’s suggestions, the division of the photos by region was abandoned in favor of by thematic groups, i.e., as a formal “atlas,” in the spirit of the early twentieth-century art historian Aby Warburg, not limited by geography or time: windows, families with children, the sick, artists’ homes, professions, and so on.

One of the key characteristics of the process of making Sociological Record was the constant evolution of the rules for the project. Over time these began to break down into several subcategories, some of which have been presented as stand-alone series, such as Myth of Photography, Women on Doorsteps, The Ill, Presence, Windows, and Disappearing Professions. Rydet’s travels and work on Sociological Record inspired her to launch successive potential expansions on the project. For example, she photographed the insides of buses, always from the seat just behind the driver so that the interior of the vehicle was reflected in the rearview mirror. Many photos in the Sociological Record archive result from an obsessive cataloguing of various objects or events (e.g., television sets, needlework, celebrations, carts, monidło hand-colored wedding photos, or tombstones), while others elude the logic of the series (oddities of all sorts, sketches for unrealized series, or visually appealing photographic “mistakes” connected, for example, with documentation of mirrors). The artist stressed many times that these subgroups constitute an equally valid part of the project and so should be presented alongside the “canonical” photos of the inhabitants of houses posing in front of walls. Below I discuss a few of the subgroups included in Sociological Record.

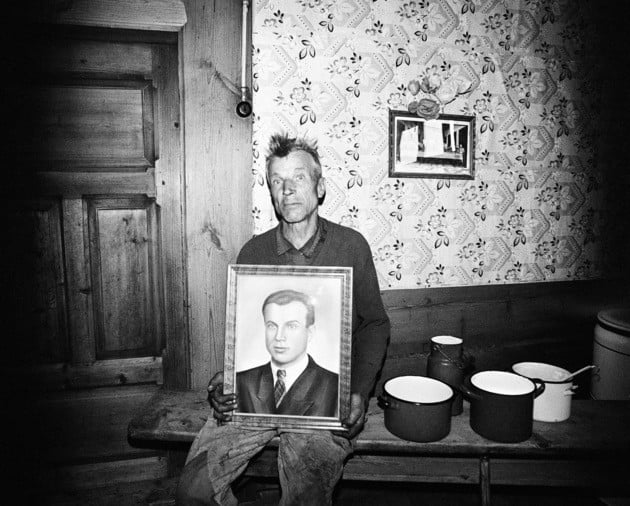

Myth of Photography

This series comprises “photographs in photographs”—documentation of walls and shelves on which private photos are displayed, and portraits of people, each holding a picture from his/her own youth (e.g., a wedding portrait, army portrait, or the like). Many of the settings were arranged by Rydet, who rearranged photos on the walls or encouraged the homeowners to pose with photos from their youth. The concept of photographing photographs lies at the foundations of Sociological Record. Archiving the photos present in private spaces was the idea behind the series, but in practice Rydet became more fascinated by the presence of the individuals in the interiors.5The idea for the series Sociological Record arose during a visit by Zofia Rydet to the Jelcz truck and bus factory in the 1970s. The artist was fascinated by the identical cubicles that the workers had personalized with press clippings, family photos, religious images, erotic posters, landscapes, etc.

The subset Myth of Photography most clearly reflects the influence of Jerzy Lewczyński,6Jerzy Lewczyński (1924–2014), a distinguished Polish photographer who developed the theory of the “archeology of photography” beginning in the 1960s. In his work he incorporated found negatives and photocopies. a photographer and close friend of Rydet, with whom she debated the role of photography in daily life and the need to erase the boundaries between professional and amateur photography, original and copy. Lewczyński said: “It should be a picture that speaks. Whether it is in a newspaper, on paper, or on cardstock is irrelevant.”7“Uboga sztuka. Z Jerzym Lewczyńskim rozmawia Magdalena Rybak” (“Arte Povera: Magdalena Rybak Interviews Jerzy Lewczyński”), typescript, December 15, 2007, archive of Jerzy Lewczyński.

Disappearing Professions

Rydet photographed people in their place of work and was particularly intrigued by small workshops, the studios of local craftsmen, small village shops, and the like, which were condemned to die out—much like village houses undergoing modernization or being abandoned by farmers migrating to the cities. This group does not include workers at large industrial plants, but some, more “modern” professionals do appear, such as secretaries, journalists, or printers. This project displays the greatest formal kinship with such historic projects as August Sander’s Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts (People of the 20th Century), the Farm Security Administration, or, on Polish soil, Jan Bułhak’s Folk Types. Rydet’s series stands out for its closer connection to its human subjects, which is far from an “inventory” or “scientific” approach to documenting reality. When gathering photos for the series, Rydet intended to create photocollages, superimposing, on the photo of the interior of the workshop, a photo of the shop’s shingle, which identifies the service provided within. Few such works were created, however.

Artists’ Homes

Rydet maintained close ties with the artistic community, including avant-garde circles, not only with the photographers in the Gliwice chapter of the Union of Polish Art Photographers. She took part in many exhibitions, lectures, and symposia throughout Poland, providing her with the opportunity to visit and document artists’ private apartments. Most of the photographs in this group were made in cities, and clearly stand out from the other groups in Sociological Record in terms of the decor and furnishings shown, e.g., the presence of book collections. The series features the homes of well-known contemporary artists such as Lewczyński, Władysław Hasior, and Józef Robakowski, alongside those of Sunday painters and folk artists. The kinetic sculptures of the engineer Jan Śliwka are found alongside bucolic landscapes by Jadwiga Malinowska, painted in a shed among heaps of grain. Some photos in the Artists’ Homes category were presented as part of Disappearing Professions, which may be treated as a wry prophecy of the exhaustion faced by the working model of the studio artist.

Women on Doorsteps

Women on Doorsteps (also referred to by Rydet as Matrons or Standing Women) is the most autonomous and consistently realized series within Sociological Record. The photographer asked women to step out of the house and pose in front of or beside the entrance. Rydet noticed that people being photographed assume a limited number of poses, from folding their arms (signaling uncertainty) to defiantly placing their hands on their hips. This typology of gestures brings to mind Conceptual art projects such as Marianne Wex’s collection of images “Let’s Take Back Our Space”: “Female” and “Male” Body Language (1972–1977). The decision to photograph women outdoors is symptomatic of the feminist approach, as Rydet stresses the strength, familial responsibilities, and charisma of the women she met. An emancipatory feminist spirit pervades the entire Sociological Record. It was created by a woman who utterly devoted her life to photography, using the camera as a tool for creating “art beyond art.”8Rasheed Araeen. Art Beyond Art: Ecoaesthetics: a Manifesto for the 21st Century. London: Third Text , 2012.

- 1Portions of Sociological Record have been presented at such shows as the XII Baltic Triennial at the Contemporary Art Centre in Vilnius, Lithuania (2015) and The Keeper at the New Museum in New York (2016).

- 2Rydet was known then primarily for two photo series published in book form: Mały człowiek (Little Person) (1965), devoted to children and adolescence, and Świat uczuć i wyobraźni (World of Emotions and Imagination) (1979), a set of collages dominated by surreal motifs—mannequins, gloves, dolls, and so on. Rydet was also interested in subjects such as state infrastructure for children and the elderly (such as orphanages, schools, social welfare homes, etc.)

- 3Urszula Czartoryska (1934–1998), art historian and curator, affiliated for decades with the Museum of Art in Łódź as director of the Department of Photography and Visual Techniques.

- 4The exhibition Zofia Rydet. Record, 1978–1990(September 2015–January 2016; curators Sebastian Cichocki and Karol Hordziej) was part of a larger research and popularization project concerning Rydet’s archive carried out by four institutions: the Foundation for Visual Arts in Poland, the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, the Zofia Rydet Foundation, and the Gliwice Museum. The fruits of these efforts include digitization and public access to nearly the entire Sociological Record and numerous source materials at the online archive www.zofiarydet.com.

- 5The idea for the series Sociological Record arose during a visit by Zofia Rydet to the Jelcz truck and bus factory in the 1970s. The artist was fascinated by the identical cubicles that the workers had personalized with press clippings, family photos, religious images, erotic posters, landscapes, etc.

- 6Jerzy Lewczyński (1924–2014), a distinguished Polish photographer who developed the theory of the “archeology of photography” beginning in the 1960s. In his work he incorporated found negatives and photocopies.

- 7“Uboga sztuka. Z Jerzym Lewczyńskim rozmawia Magdalena Rybak” (“Arte Povera: Magdalena Rybak Interviews Jerzy Lewczyński”), typescript, December 15, 2007, archive of Jerzy Lewczyński.

- 8Rasheed Araeen. Art Beyond Art: Ecoaesthetics: a Manifesto for the 21st Century. London: Third Text , 2012.